[2]

Demondion X, Lefebvre G, Fisch O, Vandenbussche L, Cepparo J, Balbi V. Radiographic anatomy of the intervertebral cervical and lumbar foramina (vessels and variants). Diagnostic and interventional imaging. 2012 Sep:93(9):690-697. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2012.07.008. Epub 2012 Aug 9

[PubMed PMID: 22883939]

[3]

Yuan SM. Aberrant Origin of Vertebral Artery and its Clinical Implications. Brazilian journal of cardiovascular surgery. 2016 Feb:31(1):52-9. doi: 10.5935/1678-9741.20150071. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27074275]

[5]

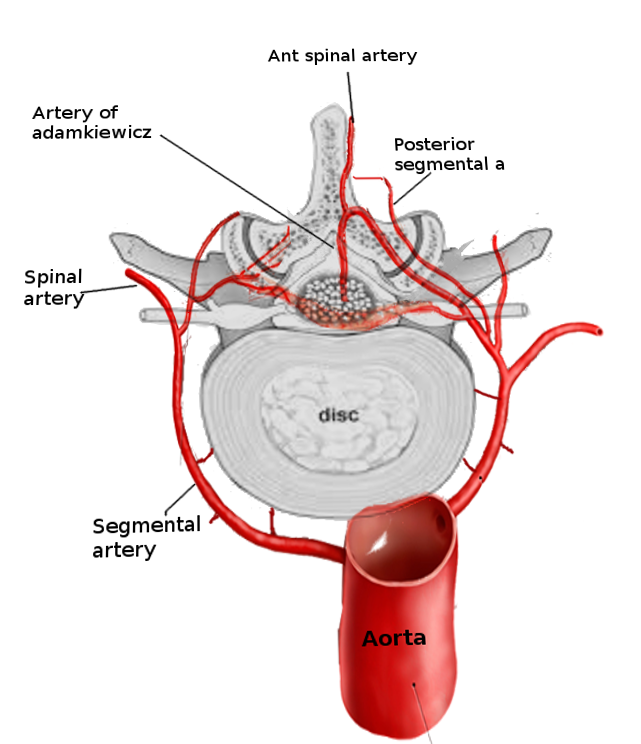

Boll DT, Bulow H, Blackham KA, Aschoff AJ, Schmitz BL. MDCT angiography of the spinal vasculature and the artery of Adamkiewicz. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2006 Oct:187(4):1054-60

[PubMed PMID: 16985157]

[7]

Singh U, Silver JR, Welply NC. Hypotensive infarction of the spinal cord. Paraplegia. 1994 May:32(5):314-22

[PubMed PMID: 8058348]

[8]

N'da HA, Chenin L, Capel C, Havet E, Le Gars D, Peltier J. Microsurgical anatomy of the Adamkiewicz artery-anterior spinal artery junction. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2016 Jul:38(5):563-7. doi: 10.1007/s00276-015-1596-3. Epub 2015 Dec 1

[PubMed PMID: 26627692]

[12]

Maccauro G, Spinelli MS, Mauro S, Perisano C, Graci C, Rosa MA. Physiopathology of spine metastasis. International journal of surgical oncology. 2011:2011():107969. doi: 10.1155/2011/107969. Epub 2011 Aug 10

[PubMed PMID: 22312491]

[13]

Hirabayashi Y, Shimizu R, Fukuda H, Saitoh K, Igarashi T. Soft tissue anatomy within the vertebral canal in pregnant women. British journal of anaesthesia. 1996 Aug:77(2):153-6

[PubMed PMID: 8881616]