Introduction

The seminal vesicles are a pair of glands that also include the prostate gland and the bulbourethral glands.[1][2][3]

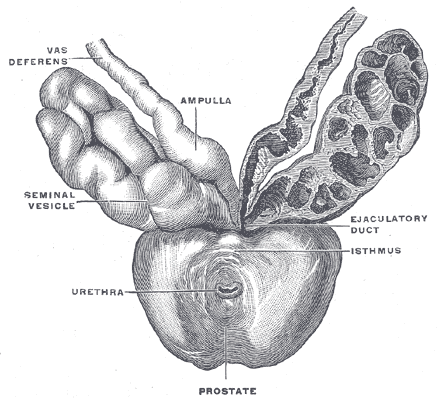

The seminal vesicles are located in the pelvis superior to the rectum, inferior to the fundus of the bladder and posterior to the prostate. Like the prostate, they are separated from the rectum by Denonvillier's fascia. Each seminal vesicle lies lateral to an ampullae of the vas deferens, a seminal vesicle ultimately converging with an ampullae to form the ejaculatory duct. These two ejaculatory ducts open into the prostatic urethra at the verumontanum, either side of the utricle.

Each seminal vesicle consists of a single, coiled, blind-ending tube giving off several irregular pouches. It is normally around 3 to 5 cm in length and 1 cm in diameter. However, when uncoiled, they are roughly 10 cm in length. Histologically, the seminal vesicles are composed of 3 layers. These include an inner mucosal layer, consisting of pseudostratified columnar epithelium with goblet cells and a lamina propria, a muscular layer, with an inner circular and outer longitudinal smooth muscle arrangement; and finally, an outer adventitial layer composed of loose areolar tissue.

Structure and Function

The seminal vesicles contribute around 70% of the fluid that will eventually become semen. The fluid that they secrete has a number of properties and components that are important for semen function and sperm survival. First, the fluid that the seminal vesicles produce is slightly alkaline in nature. This property increases the pH of the semen as a whole and counteracts the acidic environment found within the vagina. The fluid contains fructose, a sugar that provides an energy source for spermatozoa. Other components, such as proteins, enzymes, vitamin C, and prostaglandins, are also present. Semenogelin is an essential seminal vesical protein which results in the formation of a gel-like matrix that encases ejaculated spermatozoa, preventing immediate capacitation. The subsequent action of proteolytic substances such as prostate-specific antigen liquefies this matrix liberating a spermatozoon.[4][5]

The seminal vesicles are secretomotor organs composed of both secretory glandular tissue under parasympathetic control and smooth muscle under both sympathetic and parasympathetic influence. The emission phase of ejaculation, mediated through sympathetic fibers from the hypogastric nerves, leads to contractions of the seminal vesicles along with the prostate resulting in the expulsion of spermatozoa and seminal fluid into the posterior urethra.

Embryology

Seminal vesicle development closely links with the embryological development of other mesonephric or Wolffian duct structures, namely the epididymis and vas deferens. The male gonad, the testis, initially develops under the influence of the Y-chromosome. Testis development drives gonad-derived fetal testosterone production. During the 10th week of fetal development, the seminal vesicles sprout from the distal mesonephric ducts in response to testosterone. This morphogenesis of the seminal vesicles results from an androgen-dependent interaction between embryonic mesenchyme and epithelial tissues. This process contrasts with the development of the other accessory male sex glands, the prostate, and bulbourethral glands. These structures develop from the urogenital sinus under the influence of dihydrotestosterone.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The arteries supplying the seminal vesicles come from the middle and inferior vesical and middle rectal vessels. Venous drainage is via the vesical venous plexus into the internal iliac veins. Lymphatic drainage follows venous drainage and drains to both the internal and external iliac lymph nodes.

Nerves

Innervation of the seminal vesicles comes from the hypogastric nerves and the inferior hypogastric plexus. In males, the prostatic plexus derives from the inferior hypogastric plexus, while in females, it forms the uterovaginal plexus.

Physiologic Variants

Unilateral or bilateral agenesis of the seminal vesicles is rare. Unilateral agenesis or cyst formation is often associated with abnormalities from other ipsilateral, mesonephric-derived structures, such as renal agenesis. Bilateral agenesis is commonly associated with bilateral agenesis of the vas deferens. It is often related to the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator CFTR gene mutation on chromosome 7p, which can result in obstructive azoospermia.

Surgical Considerations

Surgery for isolated seminal vesicle disease is rare but is an option in cases of cysts, stones, neoplasms, or chronic infection. Increasingly, clinicians offer such surgery via minimally invasive techniques such as endoscopic, laparoscopic, or robotic approaches.[6][7][8]

Radical prostatectomy typically includes excision of the seminal vesicles, "en bloc," along with the prostate. However, their proximity to the inferior hypogastric plexus has led some to consider the preservation of the seminal vesicles in a bid to improve the recovery of urinary and sexual function post-operatively. The evidence so far suggests, although oncologically safe, there is no difference in the recovery of function compared to more standard methods of nerve-sparing technique.

Major sympathetic efferent fibers to the seminal vesicle and vas deferens originate from the hypogastric nerve, which forms the lower end of the sympathetic chain. This region is at risk during major retroperitoneal surgery, such as retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, and damage can fail emission, also known as anejaculation.

Clinical Significance

Infrequently, a range of benign and malignant conditions can affect the seminal vesicles such as stones, cysts, infection, abscess, and tumors. Infectious manifestations are more common in countries where tuberculosis and schistosomiasis are endemic. Physical examination of the seminal vesicles can be difficult, but occasionally, seminal vesicle pathology is palpable during the digital rectal exam. Urinalysis may reveal non-visible haematuria or the presence of leukocytes. Measuring fructose levels from a semen sample can provide a direct measure of seminal vesicle function. If fructose is absent, then bilateral agenesis or obstruction should be suspected.

Imaging of the seminal vesicles is achievable through a number of modalities. Trans-rectal ultrasound (TRUS) is commonly the initial investigation of choice, allowing for both diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. CT and MRI also allow imaging of the seminal vesicles and their bordering pelvic organs.

The proximity of the seminal vesicles to the prostate gland makes it a crucial adjacent structure in the staging and subsequent management of prostate cancer. The vast majority of malignant involvement of the seminal vesicles represents invasion from primary prostate cancer (pT3b).

Rarely, primary carcinoma of the seminal vesicle can present, but its histological diagnosis can be challenging to make. Most commonly, this takes the form of adenocarcinoma. However, rarer tumors such as lymphoma, sarcoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and neuroendocrine carcinoma are also possible.[9][2][10]