[1]

HerniaSurge Group. International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2018 Feb:22(1):1-165. doi: 10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x. Epub 2018 Jan 12

[PubMed PMID: 29330835]

[3]

Yoshida S, Nakagomi K, Goto S. Abscess formation in the prevesical space and bilateral thigh muscles secondary to osteomyelitis of the pubis--basis of the anatomy between the prevesical space and femoral sheath. Scandinavian journal of urology and nephrology. 2004:38(5):440-1

[PubMed PMID: 15764260]

[4]

Totté E, Van Hee R, Kox G, Hendrickx L, van Zwieten KJ. Surgical anatomy of the inguinal region: implications during inguinal laparoscopic herniorrhaphy. European surgical research. Europaische chirurgische Forschung. Recherches chirurgicales europeennes. 2005 May-Jun:37(3):185-90

[PubMed PMID: 16088185]

[5]

Benjamin M. The fascia of the limbs and back--a review. Journal of anatomy. 2009 Jan:214(1):1-18. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.01011.x. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 19166469]

[6]

Gatton ML, Pearcy MJ, Pettet GJ, Evans JH. A three-dimensional mathematical model of the thoracolumbar fascia and an estimate of its biomechanical effect. Journal of biomechanics. 2010 Oct 19:43(14):2792-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.06.022. Epub 2010 Aug 14

[PubMed PMID: 20709320]

[8]

Willard FH, Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Danneels L, Schleip R. The thoracolumbar fascia: anatomy, function and clinical considerations. Journal of anatomy. 2012 Dec:221(6):507-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01511.x. Epub 2012 May 27

[PubMed PMID: 22630613]

[9]

Kaki A, Blank N, Alraies MC, Kajy M, Grines CL, Hasan R, Htun WW, Glazier J, Mohamad T, Elder M, Schreiber T. Access and closure management of large bore femoral arterial access. Journal of interventional cardiology. 2018 Dec:31(6):969-977. doi: 10.1111/joic.12571. Epub 2018 Nov 19

[PubMed PMID: 30456854]

[10]

Scaglioni MF, Suami H. Lymphatic anatomy of the inguinal region in aid of vascularized lymph node flap harvesting. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2015 Mar:68(3):419-27. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.10.047. Epub 2014 Nov 11

[PubMed PMID: 25465766]

[11]

Shen P, Conforti AM, Essner R, Cochran AJ, Turner RR, Morton DL. Is the node of Cloquet the sentinel node for the iliac/obturator node group? Cancer journal (Sudbury, Mass.). 2000 Mar-Apr:6(2):93-7

[PubMed PMID: 11069226]

[12]

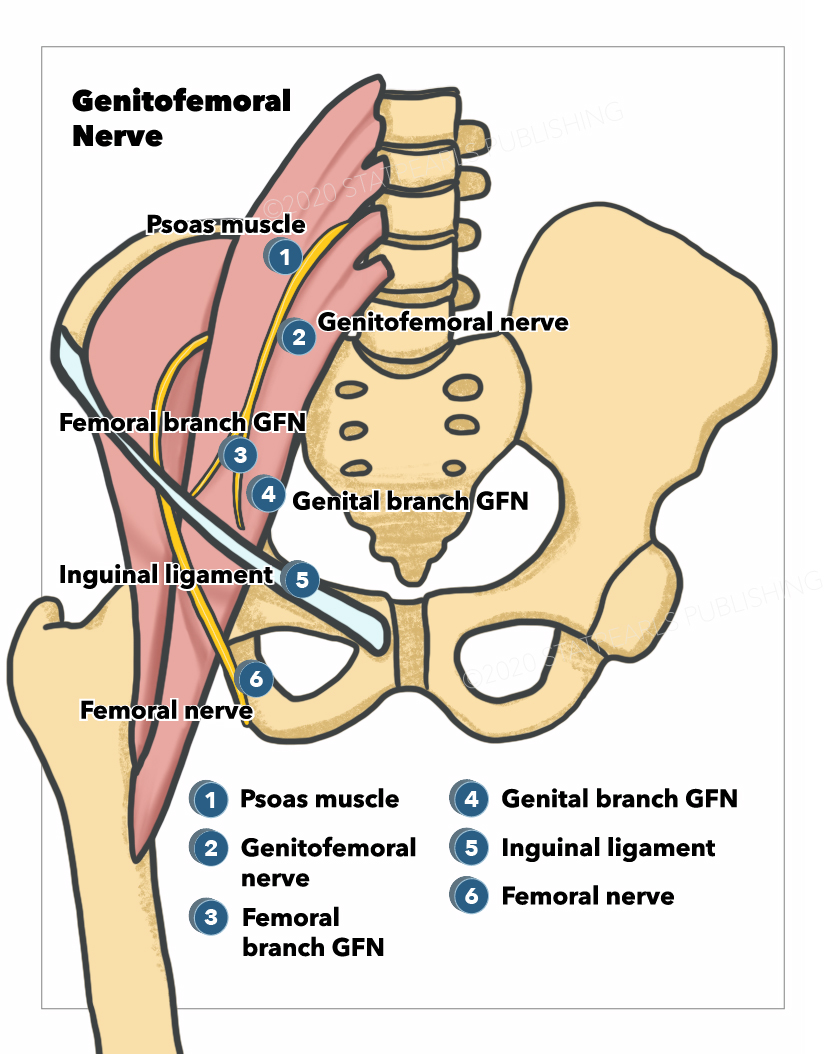

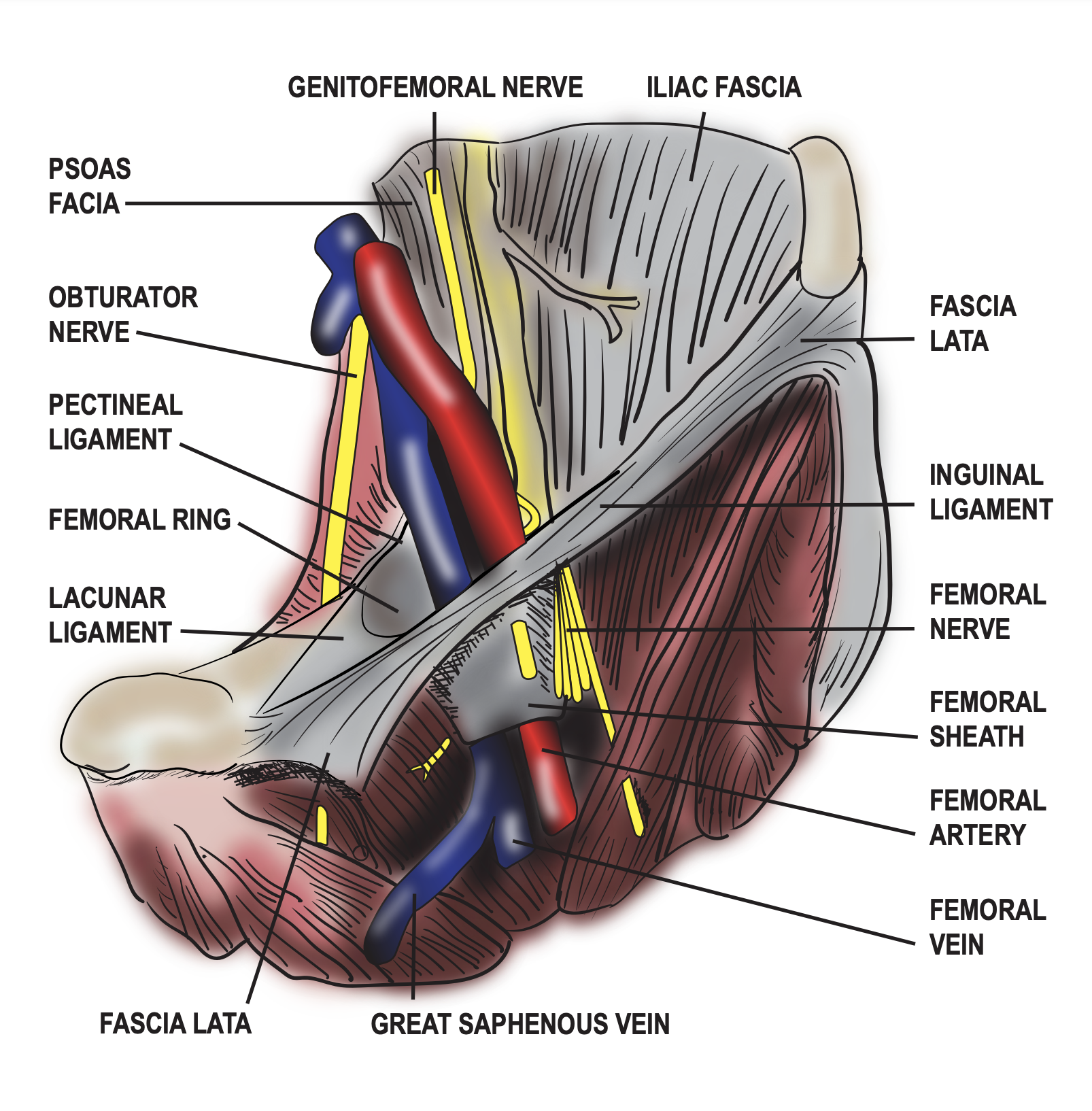

Cesmebasi A, Yadav A, Gielecki J, Tubbs RS, Loukas M. Genitofemoral neuralgia: a review. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2015 Jan:28(1):128-35. doi: 10.1002/ca.22481. Epub 2014 Nov 5

[PubMed PMID: 25377757]

[13]

Iwanaga J, Simonds E, Schumacher M, Kikuta S, Watanabe K, Tubbs RS. Revisiting the genital and femoral branches of the genitofemoral nerve: Suggestion for a more accurate terminology. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2019 Apr:32(3):458-463. doi: 10.1002/ca.23327. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30592097]

[14]

Lonchena TK,McFadden K,Orebaugh SL, Correlation of ultrasound appearance, gross anatomy, and histology of the femoral nerve at the femoral triangle. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2016 Jan;

[PubMed PMID: 25821034]

[15]

Rosenberg J, Bisgaard T, Kehlet H, Wara P, Asmussen T, Juul P, Strand L, Andersen FH, Bay-Nielsen M, Danish Hernia Database. Danish Hernia Database recommendations for the management of inguinal and femoral hernia in adults. Danish medical bulletin. 2011 Feb:58(2):C4243

[PubMed PMID: 21299930]

[16]

Clyde DR, de Beaux A, Tulloh B, O'Neill JR. Minimising recurrence after primary femoral hernia repair; is mesh mandatory? Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2020 Feb:24(1):137-142. doi: 10.1007/s10029-019-02007-6. Epub 2019 Aug 12

[PubMed PMID: 31407108]

[17]

Chen J, Lv Y, Shen Y, Liu S, Wang M. A prospective comparison of preperitoneal tension-free open herniorrhaphy with mesh plug herniorrhaphy for the treatment of femoral hernias. Surgery. 2010 Nov:148(5):976-81. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.02.006. Epub 2010 Mar 31

[PubMed PMID: 20356615]

[18]

Ceriani V, Faleschini E, Sarli D, Lodi T, Roncaglia O, Bignami P, Osio C, Somalvico F. Femoral hernia repair. Kugel retroparietal approach versus plug alloplasty: a prospective study. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2006 Apr:10(2):169-74

[PubMed PMID: 16482402]

[19]

Kang JS, Qiao F, Nie L, Wang Y, He SW, Wu B. Preperitoneal femoral hernioplasty: an "umbrella" technique. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2015 Oct:19(5):805-8. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1273-1. Epub 2014 Jun 14

[PubMed PMID: 24927966]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[20]

Chan G, Chan CK. Longterm results of a prospective study of 225 femoral hernia repairs: indications for tissue and mesh repair. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2008 Sep:207(3):360-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.04.018. Epub 2008 Jun 2

[PubMed PMID: 18722941]

[21]

Sorelli PG, El-Masry NS, Garrett WV. Open femoral hernia repair: one skin incision for all. World journal of emergency surgery : WJES. 2009 Nov 30:4():44. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-4-44. Epub 2009 Nov 30

[PubMed PMID: 19948016]

[22]

Okazaki R, Poudel S, Hane Y, Saito T, Muto J, Syoji Y, Hase R, Senmaru N, Hirano S. Laparoscopic approach as a safe and effective option for incarcerated femoral hernias. Asian journal of endoscopic surgery. 2022 Apr:15(2):328-334. doi: 10.1111/ases.13010. Epub 2021 Nov 8

[PubMed PMID: 34749433]

[23]

Peitsch WK. A modified laparoscopic hernioplasty (TAPP) is the standard procedure for inguinal and femoral hernias: a retrospective 17-year analysis with 1,123 hernia repairs. Surgical endoscopy. 2014 Feb:28(2):671-82. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3208-9. Epub 2013 Sep 17

[PubMed PMID: 24043647]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[24]

Aiolfi A, Cavalli M, Ferraro SD, Manfredini L, Bonitta G, Bruni PG, Bona D, Campanelli G. Treatment of Inguinal Hernia: Systematic Review and Updated Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Annals of surgery. 2021 Dec 1:274(6):954-961. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004735. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 33427757]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[25]

Aiolfi A, Cavalli M, Del Ferraro S, Manfredini L, Lombardo F, Bonitta G, Bruni PG, Panizzo V, Campanelli G, Bona D. Total extraperitoneal (TEP) versus laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) hernioplasty: systematic review and trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2021 Oct:25(5):1147-1157. doi: 10.1007/s10029-021-02407-7. Epub 2021 Apr 13

[PubMed PMID: 33851270]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[26]

Lockhart K, Dunn D, Teo S, Ng JY, Dhillon M, Teo E, van Driel ML. Mesh versus non-mesh for inguinal and femoral hernia repair. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Sep 13:9(9):CD011517. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011517.pub2. Epub 2018 Sep 13

[PubMed PMID: 30209805]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[27]

Kunduz E, Sormaz İC, Yapalak Y, Bektasoglu HK, Gok AF. Comparison of surgical techniques and results for emergency or elective femoral hernia repair. Ulusal travma ve acil cerrahi dergisi = Turkish journal of trauma & emergency surgery : TJTES. 2019 Nov:25(6):611-615. doi: 10.14744/tjtes.2019.04524. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 31701494]

[28]

Putnis S, Wong A, Berney C. Synchronous femoral hernias diagnosed during endoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Surgical endoscopy. 2011 Dec:25(12):3752-4. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1781-3. Epub 2011 Jun 3

[PubMed PMID: 21638171]

[29]

Alhambra-Rodriguez de Guzmán C, Picazo-Yeste J, Tenías-Burillo JM, Moreno-Sanz C. Improved outcomes of incarcerated femoral hernia: a multivariate analysis of predictive factors of bowel ischemia and potential impact on postoperative complications. American journal of surgery. 2013 Feb:205(2):188-93. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.03.011. Epub 2012 Sep 26

[PubMed PMID: 23021195]

[30]

Humes DJ, Radcliffe RS, Camm C, West J. Population-based study of presentation and adverse outcomes after femoral hernia surgery. The British journal of surgery. 2013 Dec:100(13):1827-32. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9336. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 24227371]

[31]

Wiles BM, Child N, Roberts PR. How to achieve ultrasound-guided femoral venous access: the new standard of care in the electrophysiology laboratory. Journal of interventional cardiac electrophysiology : an international journal of arrhythmias and pacing. 2017 Jun:49(1):3-9. doi: 10.1007/s10840-017-0227-9. Epub 2017 Feb 7

[PubMed PMID: 28168447]

[32]

Powell JT, Mink JT, Nomura JT, Levine BJ, Jasani N, Nichols WL, Reed J, Sierzenski PR. Ultrasound-guidance can reduce adverse events during femoral central venous cannulation. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2014 Apr:46(4):519-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.08.023. Epub 2014 Jan 22

[PubMed PMID: 24462032]

[33]

Khan Z, Nattanamai P, Keerthivaas P, Newey CR. An Evaluation of Complications in Femoral Arterial Sheaths Maintained Post-Neuroangiographic Procedures. Cureus. 2018 Feb 26:10(2):e2230. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2230. Epub 2018 Feb 26

[PubMed PMID: 29713575]

[34]

Bhatia K, Guest W, Lee H, Klostranec J, Kortman H, Orru E, Qureshi A, Kostynskyy A, Agid R, Farb R, Radovanovic I, Nicholson P, Krings T, Pereira VM. Radial vs. Femoral Artery Access for Procedural Success in Diagnostic Cerebral Angiography : A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clinical neuroradiology. 2021 Dec:31(4):1083-1091. doi: 10.1007/s00062-020-00984-1. Epub 2020 Dec 29

[PubMed PMID: 33373017]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[35]

Plata Bello A, Apatov SE, Benfante NE, Rivero Belenchón I, Picola Brau N, Mercader Barrull C, Jenjitranant P, Vickers AJ, Fine SW, Touijer KA. Prevalence of High-Risk Prostate Cancer Metastasis to Cloquet's Ilioinguinal Lymph Node. The Journal of urology. 2022 Jun:207(6):1222-1226. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000002439. Epub 2022 Jan 20

[PubMed PMID: 35050701]

[36]

Koh YX, Chok AY, Zheng H, Xu S, Teo MC. Cloquet's node trumps imaging modalities in the prediction of pelvic nodal involvement in patients with lower limb melanomas in Asian patients with palpable groin nodes. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 2014 Oct:40(10):1263-70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.05.008. Epub 2014 Jun 5

[PubMed PMID: 24947073]