Continuing Education Activity

Overuse injuries are a common entity in medical practice. Stress reactions and fractures make up a significant portion of patients in a typical sports medicine clinic. Though rare, an isolated cuboid stress fracture should be considered in a patient presenting with lateral foot pain. Due to the repetitive mechanical forces dissipated in the area, the foot is prone to overuse injuries, especially stress fractures. This activity outlines the evaluation and treatment of cuboid stress fractures and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Review the risk factors for developing a cuboid stress fracture.

Explain the common physical exam findings associated with a cuboid stress fracture.

Summarize treatment considerations for patients with cuboid stress fractures.

Summarize the importance of the interprofessional team in treatment considerations for patients with cuboid stress fractures.

Introduction

Foot conditions can be challenging to diagnose and treat due to their complex anatomy. The foot is comprised of 26 bones and 33 joints. The foot is anatomically subdivided into the hindfoot, midfoot, and forefoot. The cuboid bone is within the area of the mid-foot. This area comprises the navicular medially, three cuneiform bones, and the cuboid on the lateral side. The cuboid bone is on the most lateral aspect of the mid-foot, articulating with the calcaneus proximally and the base of the fourth and fifth metatarsals distally. Due to the repetitive mechanical forces dissipated in the area, the foot is prone to overuse injuries, especially stress fractures. Isolated stress fractures of the cuboid are rare, with a review of literature showing less than a 1% incidence. This condition should be a consideration in a patient with continual lateral foot or ankle pain, especially if the patient has persistent lateral foot pain, is athletically inclined, and has a history of repetitive use such as running, triathlon, and jumping activities such as ballet.[1]

Etiology

Stress fractures are within a spectrum of overuse injuries to the bone caused by changes in training regimens in professional athletes, highly competitive recreational athletes, and military recruits.

General risk factors for stress fractures include running, jumping, marching, decreased bone density, female gender, and poor pre-activity conditioning.[2] Furthermore, a specific triad has been associated with the female athlete involving amenorrhea, low bone mineral density, and dietary restraint. This triad has been shown to increase the risk of stress fractures by 30 to 50%.[3][4]

Increased levels of fitness activities in today's population and advanced imaging technologies have caused a rise in reported cases of stress fractures, which now make up 10% of cases in a typical sports medicine practice.[5]

The thinking regarding the underlying etiology of stress injuries to the bone is that they are the result of repeated mechanical stress, which can be either compressive or tensile.

These stresses, in particular for cuboid stress fractures, can be increased when there is overloading of the lateral column due to structural abnormalities or deficits in supportive soft tissue structures, such as weakening or rupturing the plantar fascia.[6][7]

Taken individually, the single loading does not lead to a failure of the bone cortex. However, the amalgamation of the individual loading stresses can lead to mechanical failure of the bone, leading to a stress fracture. The initial stage of bone failure is generally called a stress reaction. This diagnosis is made in a symptomatic patient who has a bone scan or MRI evidence of bone periosteal reactive changes without a true fracture line. Many factors influence the risk of stress fractures, these being divided into intrinsic (gender, age, race), extrinsic (training regimen, footwear, surface, sport), biomechanics (bone geometry), hormonal (menses abnormalities, contraception, thyroid) and nutritional (eating disorders).[5]

Epidemiology

While stress fractures of the lower extremities are common within the athletic population, cuboid stress fractures are a relatively rare entity. In a review of 196 cases of stress fractures (125 fractures in males and 71 in females), the most common site was the tibial shaft (44.4%), followed by the foot (15%), metatarsals (9.7%), and the tarsals (1%). Another study detailed 113 stress fractures in soldiers, of which the majority were in the metatarsals, and only 1 of the 113 was in the cuboid bone.[1] When found and diagnosed, these isolated cuboid stress fractures are most commonly present in endurance sport athletes (marathon, half-marathon, triathlon), but there are also reports in other sports involving large loading forces on the cuboid, including ballet, gymnastics, basketball, and rugby.

Pathophysiology

Bone remodels in response to a focal point of mechanical stress. The rate and amount of remodeling depend upon the number and frequency of loading cycles a bone is subjected (Wolff's law). An abrupt increase in the frequency, intensity, or duration of physical activity without adequate rest periods may result in pathologic bone changes. These pathologic changes result from an imbalance between bone resorption and formation. A sudden increase in exercise and training loading stress can lead to pathophysiologic adjustments and transformations in bone architecture. With periods of intense loading stress, bone resorption outweighs bone formation, making the bone very vulnerable to micro-fractures of the cortex.

With continued overload, micro-fractures may propagate (symptoms generally develop during this process) and eventually coalesce into a discontinuity within the cortical bone (i.e., a stress fracture). Continued overload can complete the fracture and result in mechanical failure with the displacement of the cortex and the development of a full fracture.[8]

History and Physical

Patients will generally present with insidious onset of pain over weeks to months. Initially, the pain is only with weight-bearing and activity. As the injury worsens, symptoms gradually progress to pain at rest, which is a cardinal symptom of a stress fracture. Activity history is usually affirmative for rapid increases in distance, duration, or training intensity. Other pertinent questions would be changes in running/playing surfaces and the amount of time rested between training events. The practitioner should also investigate menstrual history in females, nutrition (to include calcium and vitamin D intake), medications, footwear, and special equipment used (especially in a sport such as a triathlon).

There have even been instances of stress fractures of the cuboid associated with inversion ankle sprains. Suspicion of a stress fracture is warranted with prolonged pain and swelling to the lateral foot, even after weeks of conservative care.[1]

On physical examination, there is a hallmark localized point tenderness on the lateral foot, especially in the area of the cuboid bone. There may also be mild erythema and subtle soft tissue swelling over the lateral foot area. The "Nutcracker" provocation test in which the examiner stabilizes the calcaneus while the forefoot is abducted, compressing the cuboid between the calcaneus and the base of the fourth and fifth metatarsals may produce pain is specific for this injury.[9]

Evaluation

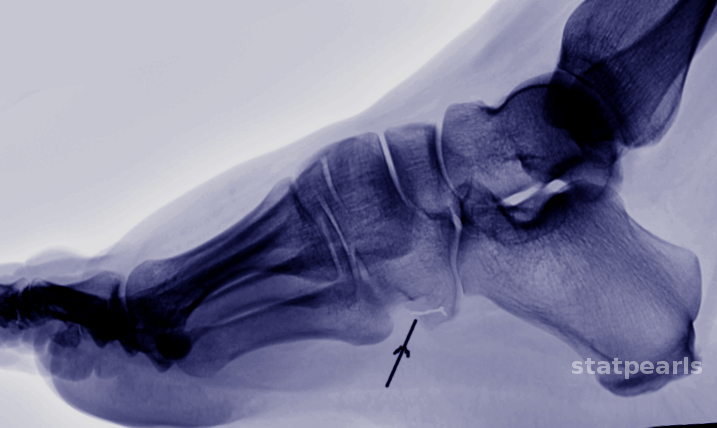

Imaging with plain radiographs is usually negative at the early stages of a stress fracture, but these studies are needed initially to differentiate other pathologies such as tumors, osteomyelitis, or occult fractures. Conventional radiographs have a sensitivity of 15% to 35% on initial examination, which increases to 30% to 70% over a 2 to 3-week period due to a more pronounced bone periosteal reaction which may be appreciated by the presence of hardly noticeable flake like patches of new bone 2 to 3 weeks after the onset of pain.[5] Advanced imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT), MRI, or radionuclide bone scan can be helpful when the diagnosis is questionable or stress fracture is suspected. In the 1970s, a bone scan was primarily used as the imaging modality of choice to diagnose a stress fracture, tracing the uptake of technetium-99m diphosphate characteristic of a stress reaction or fracture.[8]

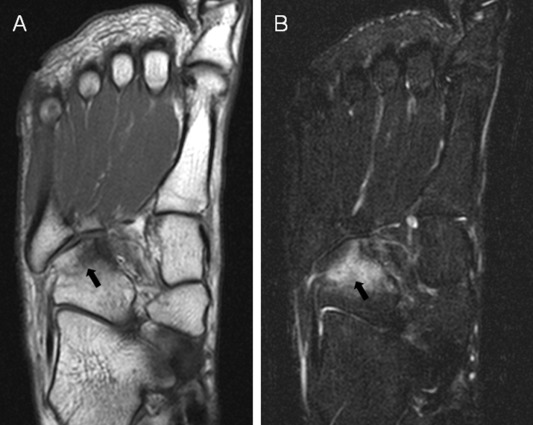

MRI has now largely replaced bone scans as the imaging modality of choice. It offers greater specificity and visual resolution over the previously used nuclear bone scan study. Bone scans, however, may still be used in some clinical situations, such as a patient with metal hardware or a pacemaker, which precludes an MRI scan. CT scan can be used to identify incomplete and complete fractures but does not help in the identification of stress reactions. CT, however, is thought to be more useful than MRI for following the healing of stress fractures. As a stress fracture heals, the initial edema seen well on MRI gets replaced by a sclerotic periosteal reaction, which a CT scan visualizes better. There is a role for diagnostic ultrasound as an adjunct to the physical examination. A recent study found the application of point-of-care ultrasound to have a positive predictive value of 99%.[8] However, the amount of training necessary in the deployment and interpretation of diagnostic bedside musculoskeletal ultrasound may limit its universal application across various practices.

MRI scan is considered the “gold standard” for diagnosing a stress fracture with a reported sensitivity near 100%.[10] It merits consideration if pain persists over two weeks with symptoms concerning for a stress fracture such as rest pain and inability to bear weight. MRI is also an option if there is a question regarding the exact diagnosis and to rule out other types of conditions which may cause pain in the lateral foot, such as peroneal tendinopathy, painful os peroneum syndrome, fracture of the anterior process of the calcaneus, or lateral ankle sprain.

Treatment / Management

An isolated cuboid stress reaction/fracture is typically manageable by a primary care clinician (who is knowledgeable and comfortable with fracture management), podiatry, sports medicine, or orthopedics. Appropriately managed, these stress fractures are among the quickest to heal, as the cuboid has a generous vascular supply. Treatment generally begins with a general evaluation, ice, and painkillers such as NSAIDs or acetaminophen.[11]

A conservative staged treatment approach is recommended starting with non-weight bearing (NWB) with crutches for the initial two weeks. Once the patient is pain-free, they move into protected weight bearing (sufficient weight-bearing to ensure the patient is pain-free). Once the patient is pain-free, the athlete can transition into a CAM boot or short-leg walking cast for another two weeks. The next few weeks are spent in a gradual return to activity of daily living (ADL), walking plus swimming, walking plus stationary cycling, walking plus the elliptical trainer. A zero-gravity treadmill is also an option for high-level athletes. Once a patient can make it through pain-free, a 6-week walk-to-run program follows. Formal physical therapy may include strengthening, range of motion, and proprioception exercises to offset any deconditioning from the period of non-weight bearing. Some patients quickly make it through the staged rehabilitation, while others may spend 1 to 2 weeks in each stage. At any point in the rehabilitation, if the pain returns, they should step back to a previous pain-free stage for 1 to 2 weeks, then gradually advance to the next stage.

Some adjunctive oral medications are found in the literature, including bisphosphonates, oral contraceptive pills, and vitamin D supplementation. With bisphosphonates, the pharmacology is the inhibition of osteoclast activity, reducing bone resorption and turnover. Bisphosphonates are primarily indicated in the treatment of osteoporosis. The role of bisphosphonates in the prevention and treatment of stress fractures is unclear. A major prospective, randomized study conducted on 324 young military recruits did not show a decreased incidence of stress fractures with the bisphosphonates group versus placebo.[8] Hormone replacement therapy via oral conceptive pills (OCPs) to increase bone mineral density is also controversial. A randomized study of 150 young female runners treated with low-dose OCP versus placebo revealed that while stress fracture incidence subjectively trended lower in the OCP group, it was not statistically significant.[8]

Evaluating possible vitamin D deficiency in athletes diagnosed with a stress fracture, especially in female patients, is a common question in practice. A recent study of 5201 U.S. Navy female recruits, which evaluated a daily vitamin D (800 international units) combined with calcium (2000 mg) vs. placebo, confirmed decreased stress fracture rates in the vitamin D/calcium group.[12] Though somewhat controversial, routine evaluation of vitamin D levels with treatment of vitamin D deficiency should still be a consideration with a stress injury diagnosis. In our military sports medicine practice, clinicians should evaluate vitamin D levels of patients with stress fractures that appear in uncommon locations and also in injuries that do not improve within the expected time frame.

Reduced calories in athletes, which requires a low BMI, such as gymnasts, dancers, and track-and-field, should undergo evaluation and treatment. In some cases, eating disorders must be ruled out, and a referral to a nutritionist or psychiatrist may be warranted. Restricted calories decrease the body of vital nutrients needed for bone metabolism, which can lead to an increased incidence of stress fractures and prolonged healing.

Bone stimulators have achieved attention in the last few years. There are currently two types of devices on the market. The first type uses electromagnetic energy that generates magnetic fields over the fracture site. The premise is that this energy can open calcium channels in cell membranes, which increase calmodulin, thus increasing cell proliferation and healing. However, no conclusive data demonstrate that electromagnetic bone stimulators enhance healing.[8] The second type is a pulsed ultrasound device that is theorized to increase vascular endothelial growth factor and fibroblast growth factor, which can promote angiogenesis. Unfortunately, literature pertaining specifically to pulsed ultrasound is limited. There was a small military study that looked at 43 tibial shaft fractures. This study concluded there was no significant difference in time to healing by adding a pulsed ultrasound bone stimulator to the usual treatment regimen of rest and activity modification.[8]

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) stimulates osteogenesis and angiogenesis and has been shown to be an effective treatment option for stress fractures.[13][14] Additionally, several level 1 studies show ESWT can produce comparable results to surgery when treating non-unions.[15][16]

Differential Diagnosis

Other overuse syndromes of the midfoot may present, like a cuboid stress fracture. These conditions include tendonitis of the peroneus brevis tendon at the insertion at the base of the fifth metatarsal. Tenderness to palpation and focal pain with resisted eversion of the foot pinpointed at the fifth metatarsal styloid will help differentiate peroneus brevis tendonitis from cuboid pathology.

Os peroneum is also a consideration; this is a rounded accessory ossicle found within the substance of the peroneus longus tendon, just lateral to the cuboid bone. This ossicle may become inflamed and irritated with repetitive activity. The presence of the ossicle on radiographs with focal tenderness strongly suggests the diagnosis.

Subluxed cuboid syndrome is another cause of lateral foot pain and has been reported to be present in approximately 7% of patients after a plantar-flexion and inversion-type ankle injury. Treatment of this condition may consist of manual manipulation techniques such as the cuboid whip maneuver, which will relieve the pain.[17]

Tarsometatarsal osteoarthritis can mimic pain caused by a cuboid stress fracture. Tarsometatarsal arthritis usually presents with the typical diurnal pain pattern of start-up pain in the morning, followed by a pain-free interval, then increasing pain with activity during the day. Physical exams alone often cannot distinguish between the two. Plain-film radiographs will often show typical features of osteoarthritis, such as joint space narrowing, osteophytes, and subchondral bone cysts within the tarsal-metatarsal joint.

Prognosis

With a rich blood supply, cuboid stress fractures are among the quickest stress fractures to heal and generally carry a good prognosis. These are considered "low-risk" stress fractures and will usually heal with nonoperative management.[8] In a case series involving six tarsal bone stress fractures, Miller et al. reported a mean expected time to return to athletic participation of 12.1 weeks in division 1 collegiate athletes.[18]

Complications

Stress fractures, in general, may have complications. Though considered a low-risk area, complications may include:

- Non-union with possible need for surgery

- Deconditioning

- Cast complications to include skin breakdown

- Excessive bone callus formation that leads to chronic pain in the area

Patients with complications should have a referral to an orthopedist, podiatrist, or sports medicine specialist.

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is important to emphasize to the coaching staff to encourage athletes to seek medical attention if they are experiencing any unusual pain or symptoms. Athlete education is also of paramount importance. Within our military sports medicine practice, we spend a great of time talking to our patients regarding proper footwear selection, training surfaces and running/race/walking techniques. Clinicians should also encourage using a shoe made specifically for running or walking versus a general type of athletic shoe. Health care providers require knowledge regarding appropriate running shoes for an athlete's foot type (normal arch, high arch, flat arch).

Additionally, athletes should be encouraged to undertake a slow, gradual increase in time, pace, and distance. Cross-training with cycling, swimming, and elliptical is also highly encouraged. Lastly, patients should receive counsel on the importance of a proper diet, including caloric intake and appropriate intake of vitamins and minerals, especially calcium and vitamin D.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team approach is optimal in treating stress fractures, especially if there are other issues involved with the patient. Physical therapy is vital for the rehabilitation stages. Athletic trainers, exercise nurses, and proper coaching can be key facets to preventing injuries by emphasizing proper form and technique. Exercise physiology and formal running coaching are essential to evaluate and correct improper running gait.

An endocrinology evaluation would benefit metabolic etiologies of low bone density. If an eating disorder, as seen in the female athlete triad patient, consultations of nutritional medicine and mental health would be crucial to ensure optimal treatment and outcomes. All these disciplines need to communicate across interprofessional lines to optimize patient care leading to the best results in managing these injuries. [Level 5]