Introduction

The thoracic aorta is subdivided into three sections: the ascending aorta, the aortic arch, and the descending aorta (see Image. Thoracic Aorta and the Aortic Arch, Computed Tomography Angiography).

The ascending thoracic aorta arises from the left ventricle of the heart, anterior to the pulmonary artery, and rises to approximately the level of the fourth thoracic vertebra. The aorta then begins to travel posteriorly and to the left, where it is known as the arch of the aorta. The normal arch of the aorta gives off three vessels. The brachiocephalic trunk, also known as the innominate artery, is the first branch, bifurcating into the right subclavian and right common carotid artery. The brachiocephalic trunk is then followed by the left common carotid and subclavian arteries. The 'typical' pattern of aortic arch vessels occurs in approximately 70% of the population. Around the vertebral level of T4, the aorta continues as the descending thoracic aorta until it reaches the diaphragm.[1][2]

Development of the Thoracic Aorta

The ascending aorta develops as a component of the primitive heart tube. The primitive heart develops from five dilations: the truncus arteriosus, conus cordis, primitive ventricle, primitive atrium, and the sinus venosus. The truncus arteriosus forms the basis for developing the ascending aorta and pulmonary trunk, beginning during the fifth week of development. The truncus starts as a single outflow tract from the right and left ventricles but is eventually divided by the aorticopulmonary septum into separate vascular outflow channels. The truncal and conal ridges are invaded by neural crest cells, leading to spiraling that forms the aorticopulmonary septum.[3]

The arch of the aorta develops from multiple structures. The portion of the arch proximal to the brachiocephalic trunk arises directly from the aortic sac. The medial area of the arch, between the brachiocephalic trunk and the left common carotid artery, arises from the left fourth aortic arch. The portion of the arch distal to the left common carotid artery arises from the dorsal aorta.

The descending aorta arises from the dorsal aortae. Early in development, paired right and left dorsal aortae are confluent with the aortic sac. The right and left dorsal aortae later fuse along vertebral levels T4 to L4, forming a single, continuous dorsal aorta. The dorsal aorta ultimately gives off many vital branches, including intersegmental, splanchnic or visceral, and umbilical arteries.[4] The dorsal aorta in this region is later referred to as the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta.

Development

The Aortic Sac

The aortic sac is the first portion of the aorta to form, appearing as a dilated structure superior to the truncus arteriosus. The aortic sac then develops two horns, inevitably leading to important aortic structures. The right horn gives rise to the brachiocephalic artery, while the left horn combines with the stem of the aortic sac to form the portion of the aortic arch proximal to the brachiocephalic trunk. The aortic arches develop from the aortic sac and proceed to course into the pharyngeal arches.

The Aortic Arches

The aortic arches or pharyngeal arch arteries or branchial arches develop from the aortic sac, with a pair of branches (right and left) traveling within each pharyngeal arch and ending in the dorsal aorta. Initially, the arches arise in symmetrical pairs, but after remodeling, the arches become asymmetric, and several of the arches regress. All six pairs are not present simultaneously; they develop and regress at different stages.

- First aortic arch - regresses early, but a remnant forms a portion of the maxillary artery.

- Second aortic arch - regresses early, but a remnant forms portions of the hyoid and stapedial arteries.

- Third aortic arch - contributes to the formation of the common carotid arteries bilaterally and the proximal internal carotid arteries bilaterally.

- Fourth aortic arch - The right arch contributes to the R proximal subclavian artery. The left arch gives rise to the medial portion of the aortic arch.

- Fifth aortic arch - never forms or incompletely forms and regresses.

- Sixth aortic arch - The right and left arches separate into ventral and dorsal segments. The ventral segments are responsible for the formation of the pulmonary arteries bilaterally. The left ventral arch also contributes to the formation of the pulmonary trunk. The right dorsal arch regresses. The left dorsal arch forms the ductus arteriosus, which later closes and is termed the ligamentum arteriosum.

The Dorsal Aorta

The right and left dorsal aortae arise from the aortic sac and receive the aortic arches bilaterally. At the level of the aortic arches, the dorsal aortae remain paired but inferior fuse inferiorly (below T4) to form the descending aorta. The dorsal aortae give off seven cervical intersegmental arteries bilaterally. The upper six contribute to developing the vertebral, superior intercostal, and deep cervical arteries. The seventh intersegmental arteries contribute to the formation of the subclavian arteries bilaterally. The right dorsal aorta typically regresses between the origin of the seventh intersegmental artery and the site of fusion with the left dorsal aorta. The splanchnic or visceral arteries eventually give rise to ventral branches (the celiac, superior mesenteric artery, and inferior mesenteric artery) and lateral branches (suprarenal, renal, and gonadal arteries).

Cellular

The aortic arch is made up of several layers of cells. The intimal layer consists of endothelial cells, connective fibers under the endothelial cells, and an internal lamina. In the medium tunica, which is the thickest compared to the other arteries of the body, one can find smooth muscle cells and extracellular matrix. Another layer is the adventitia, formed from connective tissue that wraps around the nerves (nervi vascularis) and blood vessels (vasa vasorum). This tract of the artery is essential because it must manage the blood pressure coming from the left ventricle, adapting to the speed of the flow, the direction, and the quantity of the same blood flow (mechanotransduction). The volume of the aortic tissue is isochoric; it is kept constant in its form and histological characteristics in a physiological and healthy environment.

Molecular Level

In the development and maintenance of the structure of the aortic arch, many molecules take over. For example, in an adult structure, the passage of blood stimulates endothelial cells to express the following:

- Vascular endothelial growth factor-C or VEGF-C

- Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 or PECAM-1

- Vascular endothelial cell cadherin or VE-cadherin

- Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 or VEGFR2

- Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase or PI3K

- Platelet-derived growth factor or PDGF

- Transforming growth factor-beta or TGF beta

- Endothelial nitric oxide synthase or eNOS

During development, many of these molecules play fundamental roles in recruiting cells that will build the aortic arch, such as platelet-derived growth factor B or PDGFB. The latter will activate the receptors on smooth muscle cells and pericytes. These cells will, in turn, produce Ang-1 (angiopoietin-1), which will serve to bind these different cells together by activating the endothelial receptor Tie2.[5]

Pathophysiology

Due to the complexity of the development of the aortic arch, a number of congenital abnormalities are possible. Malformations result from the persistence of structures that typically regress or the regression of structures that usually persist.[6]

Abnormalities of Aortic Arch Vessels

Common Origin of Brachiocephalic Trunk and Left Common Carotid Artery - Instead of arising from the arch of the aorta as distinct branches, the left common carotid artery and the brachiocephalic trunk both arise from a common origin. In this variant, only two vessels (the common trunk and the left subclavian) branch directly off the arch of the aorta. This arrangement is the second most common branching pattern, following the 'normal' pattern detailed above, occurring in approximately 13% of the population.[7]

This pattern is often incorrectly termed the 'bovine aortic arch.' A true bovine arch consists of a single vessel arising from the aortic arch. This vessel then gives rise to the subclavian arteries bilaterally and a common carotid trunk, bifurcating into the right and left common carotid arteries. This vessel pattern is not present in humans.

Origin of Left Common Carotid Artery from the Brachiocephalic Trunk - This pattern is very similar to the typical origin pattern detailed above. Two vessels arise from the arch of the aorta, the brachiocephalic trunk and the left common carotid artery. But in this situation, the left common carotid artery originates distally, directly off the brachiocephalic trunk, rather than from a common origin. Typically, the common carotid originates less than 1 cm from the aortic arch.[7]

Aberrant Right Subclavian Artery (ARSA) - Occurring in approximately 1% of the population, the right subclavian artery is the final branch arising off the aortic arch, occurring distal to the takeoff of the left subclavian artery. This formation occurs secondary to abnormal regression of the R fourth aortic arch, causing loss of the normal proximal portion of the right subclavian. The artery arises entirely from the right seventh segmental artery, from the dorsal aorta. To reach the right upper extremity, the aberrant artery most commonly (80% of cases) crosses the midline posterior to the esophagus. The other routes are between the trachea and esophagus (15% of cases) and anterior to the trachea (5%). This condition is generally asymptomatic but can cause esophageal compression or dysphagia, stridor, or recurrent laryngeal nerve compression.

One case report details retro-esophageal ARSA presenting with tracheoesophageal fistula formation, suspected secondary to chronic compression.[8]

Anomalous Origin of Vertebral Artery - In approximately 5% of cases, the left vertebral artery arises from the aortic arch, frequently between the left common carotid and subclavian arteries. The proximal portion can be duplicated, arising from the aortic arch and the left subclavian artery, before merging into a single artery.[9]

There have been case reports of bilateral vertebral arteries arising from the aortic arch, both arising between the left common carotid and left subclavian arteries, both arising distal to the left subclavian artery, or the left vertebral originating between the left common carotid and left subclavian artery while the right vertebral artery originates distal to the left subclavian artery.[10][11][12]

Patent Ductus Arteriosus - The ductus arteriosus arises from the dorsal left sixth aortic arch and connects the pulmonary artery to the aorta. This connection is an important aspect of fetal circulation, allowing oxygenated blood to bypass the fluid-filled lungs that do not participate in gas exchange. The ductus arteriosus typically closes in the first three days of life, forming a fibrous cord called the ligamentum arteriosum. When the ductus fails to close, it creates a left-to-right shunt due to increased resistance in the systemic circulation compared to pulmonary circulation. If the defect is large enough, it can lead to pulmonary hypertension and early-onset heart failure. The risk for a persistent ductus arteriosus increases as the birth age decreases. PDA classically presents with a continuous 'machine-like' murmur radiating to the back.[13][14]

Abnormalities of the Arch of the Aorta

Truncus Arteriosus - A rare congenital heart defect presenting with a common ventricular outflow tract and a ventricular septal defect. It occurs secondary to abnormal aorticopulmonary septum formation, frequently attributed to improper neural crest cell migration. It is frequently associated with 22q11 gene deletions or mutations. During early life, pulmonary vascular resistance is relatively high, leading to right-to-left shunting and cyanosis in the infant. These defects require early surgical repair within the first month of life.[15]

Coarctation of the Aorta - An area of stenosis in the aorta, most commonly in the thoracic aorta, but it can also occur in the abdominal aorta. This anatomy occurs in less than 0.1% of the population. They are classified into pre-ductal and post-ductal types. Post-ductal lesions are most common and present distally to the ductus arteriosus. Pre-ductal lesions occur less commonly and present proximally to the ductus arteriosus. Traditionally, coarctation classifies as infantile (pre-ductal) and adult (post-ductal), but this classification was abandoned as the age of presentation is more related to the severity of stenosis, as opposed to the location. The most common presentation is a differential between the blood pressure of the upper and lower extremities. Coarctation is repairable with surgical removal of the stenotic segment or transcatheter stenting.[16] There have been reports of coarctation in right-sided aortic arches, as well.[17]

Interrupted Aortic Arch (IAA) - A severe version of coarctation of the aorta, which presents with a complete luminal interruption between the ascending and descending aorta. This malformation is incompatible with life without a patent ductus arteriosus to allow for left ventricular outflow and systemic blood delivery. Interrupted arches get classified by the site of disruption, with type A occurring distal to the left subclavian (13% of cases), type B between the left subclavian and left common carotid (84% of cases), and type C occurring proximal to the left common carotid artery. IAA most commonly presents in infancy due to absent blood flow to the extremities. PGE1 is necessary to maintain a patent ductus arteriosus, which requires surgical repair.[18]

One case report details a case of isolated Type B IAA discovered in a 70-year-old patient who had never undergone intervention. CTA demonstrated extensive collateral blood flow, and conservative therapy followed.[19]

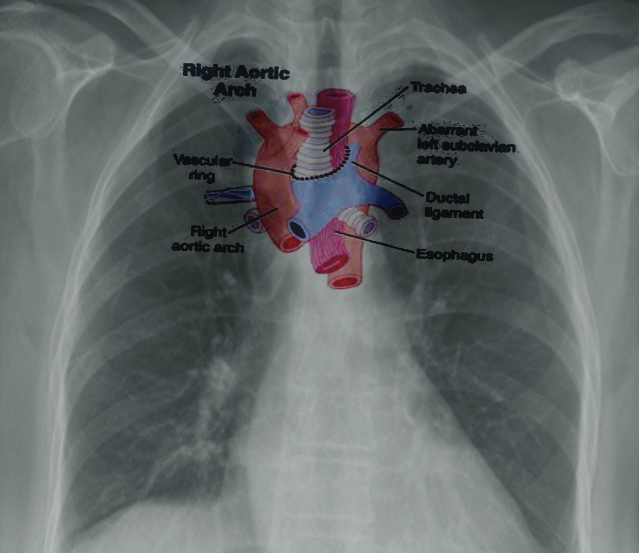

Right-Sided Aortic Arch - An uncommon anomaly (presenting in less than 0.1% of the population) where the aortic arch traverses the right bronchus instead of the left bronchus. This condition occurs due to the persistence of the right dorsal aorta with the regression of the left dorsal aorta. The most common presentation (approximately 60%) is the 'mirror-type,' with a right-sided arch and a left brachiocephalic trunk, right common carotid, and right subclavian arteries. The 'mirror type' is strongly associated with other congenital heart defects. The next most common presentation (approximately 40%) is a right-sided aortic arch with an aberrant left subclavian artery; this mimics the ARSA pattern, with the left common carotid arising first, followed by the right common carotid, right subclavian, and then left subclavian arteries. As with traditional ARSA, this leads to the formation of a vascular ring and symptoms of tracheal or esophageal compression. Patients with a right-sided arch but a left-sided ligamentum arteriosum can also demonstrate symptoms of vascular ring.[20] See Image. Right Aortic Arch.

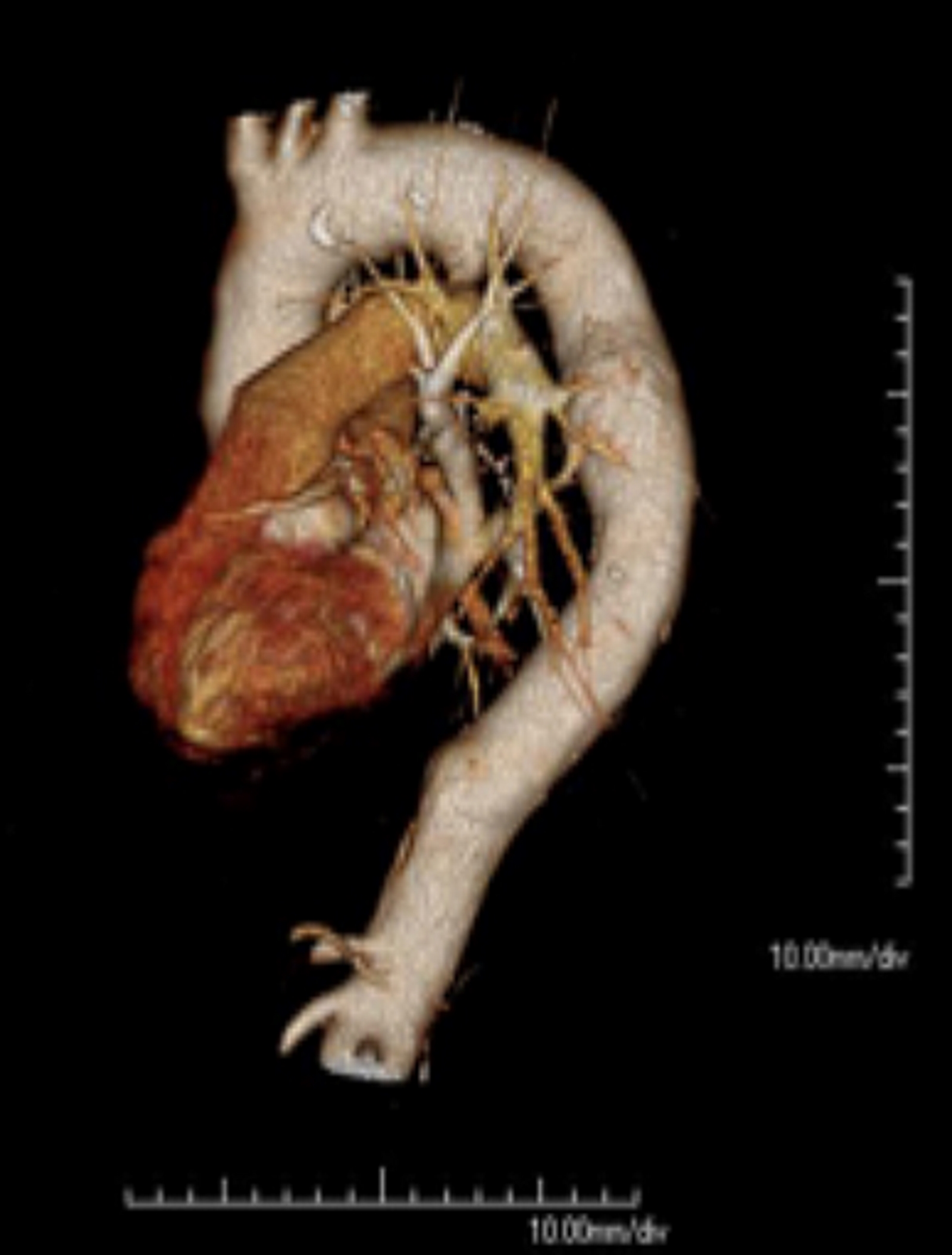

Double Aortic Arch - A rare malformation of the aorta, with a division of the ascending aorta into two arches. These arches generally surround the trachea/esophagus, forming a vascular ring, which most commonly occurs secondary to the persistence of the right fourth aortic arch. Generally, the arches are asymmetric, with 70% presenting as right-side dominant and 25% as left-side dominant. Balanced arches occur only 5% of the time, and the typical presentation in the neonate with symptoms of esophageal or tracheal compression (swallowing disorders, expiratory stridor). Swallowing difficulty can present with respiratory symptoms secondary to recurrent aspiration. Surgical division of the vascular ring is indicated for symptomatic patients, but persistent respiratory symptoms are common due to improper development of the trachea.[21][22] See Image. Cardiac Computed Tomography, Double Aortic Arch.

Persistent Fifth Aortic Arch (PFAA) - This is a rare congenital condition where the fifth aortic arch fails to degenerate unilaterally.[23] Some suspect that the condition is underrecognized, as opposed to truly uncommon.[24] Others doubt that the condition exists at all.[25] PFAA can present in two primary fashions. In the first type, the persistent arch connects the ascending and descending aorta underneath the fourth arch. This leads to a double aortic arch that does not surround the trachea or esophagus. This type has limited consequences functionally or hemodynamically. One case report details a case of a PFAA in a patient associated with aortic coarctation. The surgical repair involved a side-to-side anastomosis, allowing for enlargement of the coarctation and elimination of the double aortic arch.[26]

In the second type, the persistent fifth arch merges with a portion of the sixth aortic arch, leading to a systemic-pulmonary shunt. It most commonly occurs in conjunction with other congenital heart defects, including pulmonary atresia and truncus arteriosus. Thus, the shunt is beneficial, as it allows for increased blood delivery to the pulmonary system in these conditions. In patients without an associated defect, this shunt can lead to heart failure in patients as young as two months.[27]

There have been suggestions that rare cases of the left pulmonary artery arising from the ascending aorta can be attributed to PFAA. The belief is that the sixth aortic arch fails to develop, and the left fifth aortic arch persists, creating the anomalous pulmonary artery.[28] One case report details a patient with a double-lumen aortic arch and an anomalous left pulmonary artery originating from the ascending aorta. The authors suggest it as a case of bilateral PFAA, with the right fifth aortic arch creating the double-lumen aorta and the left fifth aortic arch creating the anomalous pulmonary artery.[29]

Cervical Aortic Arch - A rare aortic arch anomaly with a very high location of the aortic arch; this occurs due to the persistence of the third aortic arch, with regression of the fourth aortic arch during development. The arch is typically located in the mid-neck and commonly presents with a right-sided aortic arch. These are frequently asymptomatic but can present with tracheal compression symptoms, esophageal compression, or a pulsatile mass in the neck.[30][31]

Clinical Significance

Recurrent Laryngeal Nerves - The recurrent laryngeal nerves are direct branches of the vagus nerve, which supply the intrinsic muscles of the larynx in the adult. While they are symmetric in development, they diverge in the adult. The right recurrent laryngeal nerve loops under the right subclavian artery, while the left recurrent laryngeal nerve loops under the arch of the aorta. The recurrent laryngeal nerves develop from the sixth pharyngeal arch bilaterally, but in the growing fetus, the heart migrates inferiorly, leading to their eventual asymmetry. As the heart descends, the nerves loop around the sixth aortic arch and ascend to the larynx. On the right, as the dorsal right sixth aortic arch regresses (as does the fifth aortic arch), the recurrent laryngeal nerve elevates to the fourth aortic arch; this leads to its adult location, inferior to the right subclavian artery. On the left, the dorsal left sixth aortic arch persists and develops into the ductus arteriosus; thus, the left recurrent laryngeal nerve does not elevate, leading to the left recurrent laryngeal nerve remaining inferior to the arch of the aorta, lateral to the ligamentum arteriosum.

Aberrant Right Subclavian Artery - This defect is particularly relevant in thoracic surgery, particularly esophageal dissection or esophagectomy. Lack of knowledge and understanding of this abnormality, present in 0.5 to 1.8% of the population, can lead to life-threatening bleeding during esophageal manipulation.[32][33]