Continuing Education Activity

Double aortic arch is the commonest form of a group of defects that affect the development of the aorta. This defect causes an abnormal circular formation of blood vessels, called a vascular ring, that can result in life-threatening airway obstruction. To avoid the high morbidity and mortality associated with this condition, it must be thought of and promptly diagnosed and treated. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of a double aortic arch and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the embryological etiology of a double aortic arch.

- Explain the evaluation process in cases of a double aortic arch.

- Outline the surgical management of a double aortic arch.

- Discuss interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication in the management of a double aortic arch.

Introduction

Double aortic arch is the most common type of vascular ring malformation. It involves the complete encirclement and compression of the trachea and/or esophagus by the aortic arch, its branches, or atretic ligamentous segments. Left untreated, it may lead to significant morbidity for the patient and can result in sudden death from airway compromise. Hommel described the first post-mortem case in 1737, with the first documented surgical repair only being carried out by Robert Gross in 1947.[1]

Etiology

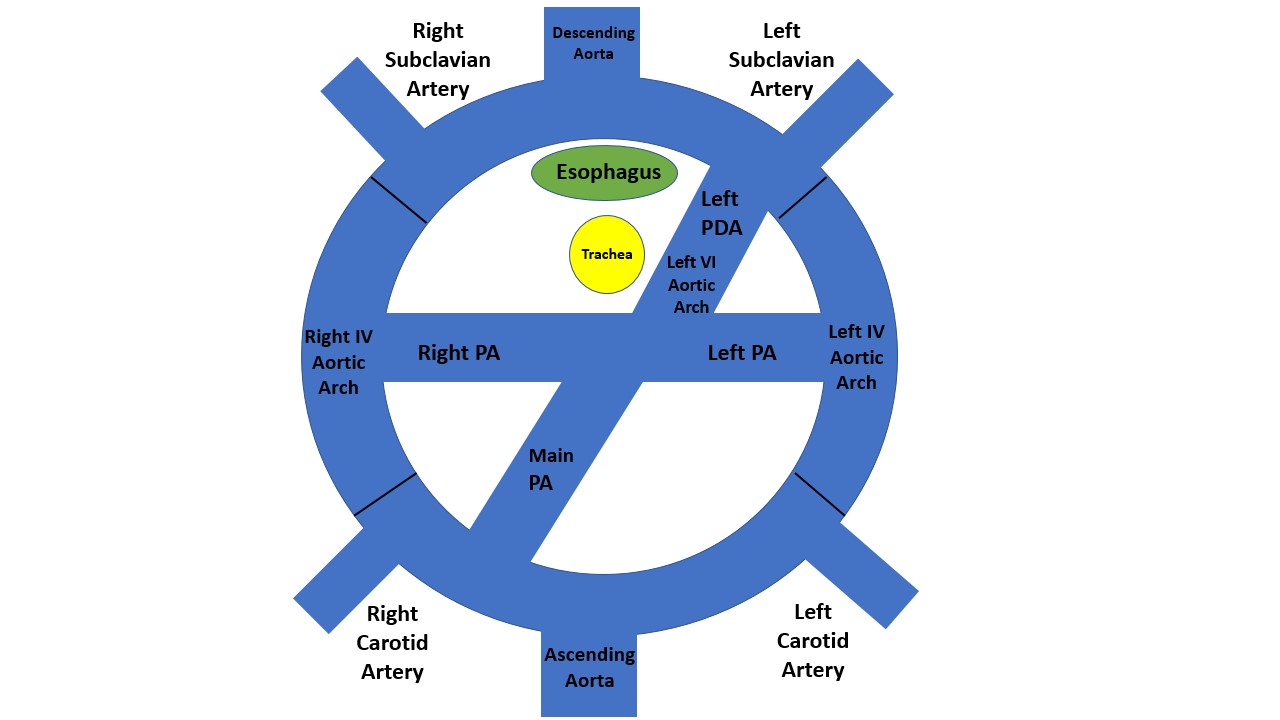

Aortic arch development is a complex process that occurs between weeks two and seven of gestational life. Six pairs of arches emerge and regress in a sequential fashion leaving remnants that form important vessels. This setup forms the basis of the aortic arch variants and anomalies. The first two arches disappear early, leaving the maxillary, hyoid, and stapedial arteries. The third branch forms the common carotid arteries and a small portion of the internal carotid arteries. The fourth pair of arches give rise to the bilateral aortic arches. In week five of gestation, the right-sided arch regresses, and the left-sided arch remains, leaving a normal left-sided aortic arch.

Failure of the regression of the right-sided arch with the persistence of the left-sided arch leads to the formation of a double aortic arch. Conversely, a solitary right-sided aortic arch may remain if the left-sided arch regresses while the right-sided arch persists. Three types of double aortic arches have been described and include (in order of decreasing frequency) dominant right-arch with small left-arch, dominant left-arch with small right-arch and balanced aortic-arches. The fifth pair of arches do not contribute to significant vasculature, whereas the anterior bud of the sixth pair of arches gives rise to the pulmonary arterial trunk and ductal artery.[2][3][4]

Epidemiology

The incidence of double aortic arch is generally unknown. Published data estimates the prevalence of vascular rings to be 1%. Up to 55% of patients undergoing vascular ring repair have a double aortic arch. There is no predilection towards a particular sex or race. An underlying cardiac diagnosis is prevalent in up to 12.6% and includes ventricular septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, and other complex congenital cardiac conditions. There is an association with chromosome 22q11 deletion, trisomy 21, and other syndromes in up to 20% of cases. A 2 to 3 fold increase in the incidence of double aortic arch has been reported with the use of routine first-trimester ultrasound compared to postnatal data, with risk increasing significantly in those conceived via in-vitro fertilization.[5][6]

History and Physical

The presentation of a double aortic arch depends largely on the existence of hemodynamic instability. Children with double aortic arch tend to present earlier than those with the other vascular ring pathology, the right-sided aortic arch.

They may remain undiagnosed, rarely may be diagnosed during fetal echocardiography, and often are identified as an incidental finding during routine imaging for other indications. There are reported cases of double aortic arch being diagnosed after foreign body ingestion, and in an adult with aortic dissection.[7][8]

Due to the anatomic nature of the lesion and based on the degree of compression on the trachea and/or esophagus, patients may present with respiratory failure shortly after birth, apneic episodes, apparent life-threatening events (ALTE) or brief resolved unexplained events (BRUE), noisy breathing which may include stridor or wheeze, cyanosis, persistent cough, recurrent lower respiratory tract infections, misdiagnosed ‘asthma’ resistant to therapy, choking, regurgitation, persistent dysphagia, and failure to thrive. Exercise tolerance may be limited due to symptoms.[5][9][10]

Physical examination may often be entirely normal but can include evidence of poor growth and feed intolerance, non-positional stridor, respiratory distress, and features of a lower respiratory infection such as bronchial breath sounds and crackle.[11][12]

Evaluation

Laboratory tests are rarely helpful in the diagnosis of a double aortic arch but may aid in the diagnosis of additional conditions that may be present such as genetic testing for underlying conditions and full blood count to assist in the diagnosis of respiratory infections. Imaging remains the mainstay of investigation. Echocardiography is the first test of choice, can evaluate the nature of the aortic arch and its branches and can identify other intra-cardiac anomalies that may also be present.

Electrocardiographic studies are normal unless intra-cardiac structural anomalies are co-existent.

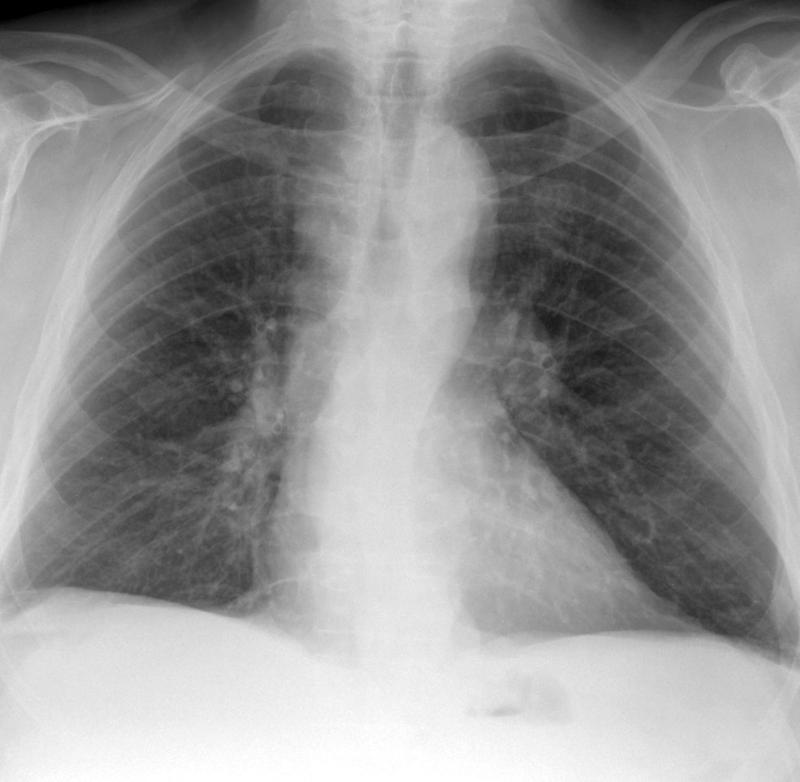

Plain chest roentgenogram can reveal loss of aortic knob, lateral/posterior indentation of the trachea, while barium swallow can show indentation of the esophagus. These do not rate as essential diagnostic studies.

Advanced imaging using computer tomography or magnetic resonance imaging has become the diagnostic procedure of choice, permitting clear delineation of the aortic arches, its location and branching pattern, arch dominance, adjacent tissue, and extend of tracheal/oesophageal compression. It also holds value in pre-operative planning. It typically takes place after echocardiography.

Bronchoscopy usually occurs pre-operatively to evaluate airway anatomy and to rule out other airway causes for respiratory symptoms. It may also help to confirm and grade the severity of airway compression. It is seldom useful postoperatively to determine the efficacy of decompression.[5][13][14]

Treatment / Management

Surgical repair remains the mainstay of treatment and is indicated for patients with symptoms of tracheal and/or oesophageal compression or as a supplementary procedure in patients undergoing repair of other cardiothoracic abnormalities.

The principle of surgery is to relieve the vascular compression on the trachea and/or esophagus by the division of the lesser arch. This process occurs under general anesthesia via an ipsilateral muscle-sparing thoracotomy and does not involve cardiopulmonary bypass.

The forth-intercostal space is usually used to gain access to the chest cavity. After retraction of the lung and opening of the pleura, the vascular ring and main adjacent structures such as the esophagus, trachea, phrenic nerve, vagus nerve, and recurrent laryngeal nerve are identified and protected. The location of the arch intended for the division is temporarily occluded to ensure patent blood supply to the vessels supplying the head and lower body. The surgeon then undertakes staged division and oversewing while ensuring hemostasis is maintained. A drain is occasionally left in place to monitor for chylothorax or residual hemorrhage.[12]

Differential Diagnosis

- Laryngomalacia

- Tracheomalacia

- Bronchiolitis

- Viral induced wheeze

- Lower respiratory tract infection

- Subglottic stenosis

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

Prognosis

Patients who have undergone double aortic arch repair have an excellent prognosis, with usually no implication physical activity and lifestyle. There is no increased risk for the development of arrhythmias or sudden death. Pregnancy may be undertaken routinely, with the recommendation for routine fetal echocardiography, in females who have undergone repair with no significant residual airway obstruction.

Complications

Immediate postoperative complications are uncommon but include feed intolerance and persistence of airway symptoms such as cough, difficulty breathing, stridor, and wheeze. Rarely, intra-operative injury to the phrenic nerve, recurrent laryngeal nerve, or thoracic duct may result in paralysis of the diaphragm, vocal cord paralysis, and chylothorax respectively. Postoperative formation of aorto-oesophageal fistula and oesophageal erosion are very rare.[15]

Consultations

- Cardiologist

- Cardiothoracic surgeon

- Pediatrician

- Geneticist

Deterrence and Patient Education

Once a diagnosis is made and surgery awaited, parents should receive counsel about symptoms that should prompt them to seek professional help immediately due to the potential for fatal airway compromise. Care is necessary so as not to intensify the pre-existing anxiety of the family.

Parents should also be counseled regarding the possibility of persistent noisy breathing up to a year post-surgery, due to tracheomalacia and/or bronchomalacia caused by the vascular ring.

Pearls and Other Issues

Children presenting with persistent noisy breathing, persistent cough, or recurrent lower respiratory tract infections may be misdiagnosed with primary respiratory pathology such as Asthma. The key to a diagnosis of a double aortic arch is to have a clinical suspicion and awareness of the condition. Such cases may benefit from baseline non-invasive investigative studies such as echocardiography.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Early clinical suspicion, diagnosis, and surgical management of a double aortic arch can prevent long-term respiratory complications.

An interprofessional team comprising of a cardiologist, cardiothoracic surgeon, pediatrician, respiratory physician, anesthetist, intensive care nurse, therapist, and geneticist normally engages in the care of the patient with a double aortic arch. Other healthcare professionals should be involved when additional conditions mandating specialist input co-exist.

Early postoperative extubation and adequate postoperative pain management strategies aid in improving patient satisfaction and reducing the length of hospital stay.