Introduction

A sinus is defined as:

- A channel that is not a blood or lymphatic vessel that allows for the passage of blood or lymph, such as found in the placenta, sinuses, or the cerebral meninges

- A cavity or hollow space in bone or other tissue

- A dilation in a blood vessel

- A fistula or tract that transforms into a cavity

There are many types of sinuses, such as the paranasal sinuses of the skull or the dural sinuses of the cerebral meninges. The pericardial sinuses are formed during embryological development as a consequence of heart formation and act as important structures for cardiothoracic surgeons to place ligature for vessel occlusion during surgery. This article will focus on the anatomical sinuses of the nasal and paranasal areas.[1][2][3]

Sinuses are located throughout the body and perform varying functions. Sinuses are typically associated with the cavities within the skull. The word “sinus” is most commonly understood to be the paranasal sinuses that are located near the nose and connect to the nasal cavity. There are four paranasal sinuses, each corresponding with the respective bone from which it takes its name: maxillary, ethmoid, sphenoid, and frontal. Sinuses also exist in the dura of the brain, which includes the superior sagittal, straight, and the sigmoid, among others. These dural venous sinuses function as the brain’s venous system. Other sinuses are in the kidney, heart, and lymphatic system.

Structure and Function

Paranasal Sinuses

The total function of the paranasal sinuses is unclear. The cavities allow for the increase in the bony structure without adding significant mass. They also provide social cues that indicate such things as gender and sexual maturity. Respiratory mucosa lines the paranasal sinuses. This respiratory mucosa is ciliated and secretes mucus.

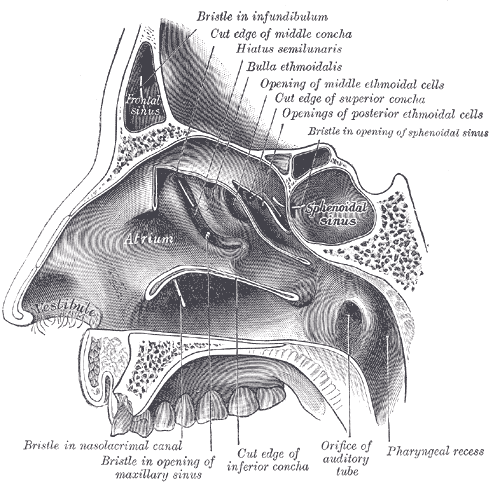

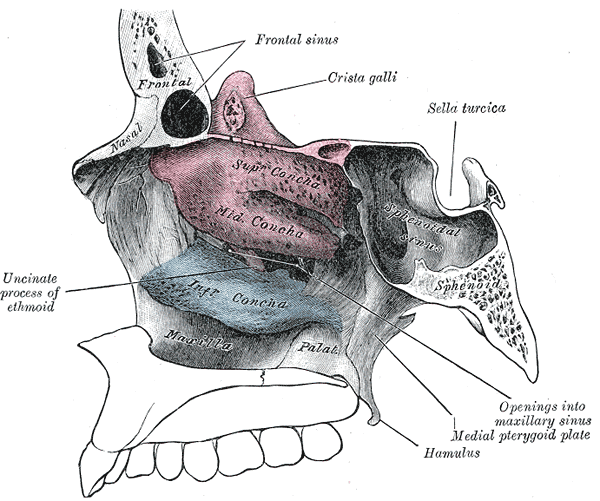

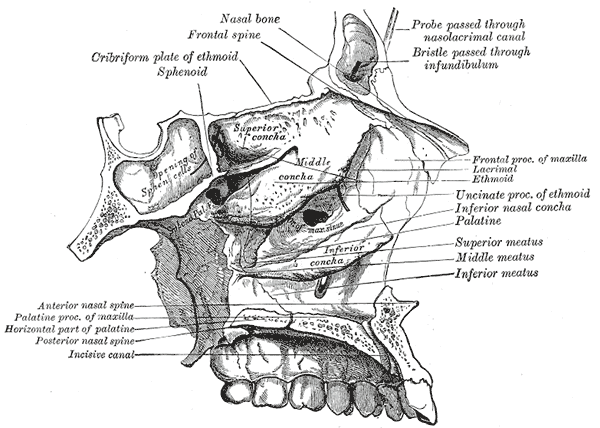

The ethmoid sinuses are between the orbits. They typically are formed by a series of labyrinths, which vary in number from 3 to 18. These ethmoidal air cells are divided regionally into anterior, middle, and posterior, based on the location of their apertures. The anterior ethmoidal sinus opens into the ethmoidal infundibulum or the frontonasal duct. The middle group opens into the ethmoidal bulla or just superior to it. The posterior group opens onto the lateral wall of the superior nasal meatus.

The largest of the paranasal sinuses is the maxillary sinus. There are two pyramidal-shaped maxillary sinuses located bilaterally in the maxilla of the face. It fills the bone in its entirety to reduce the mass of the maxilla. The maxillary sinus opens into the center of the semilunar hiatus found in the lateral wall of the middle nasal meatus.

The triangular-shaped frontal sinuses are in the frontal bone superior to the orbits. These sinuses vary in size. They open at the lateral wall of the middle meatus, which then continues as the semilunar hiatus, which drains the maxillary sinus.

Finally, the sphenoidal sinuses are in the body of the sphenoid. They open into the posterior wall of the sphenoid-ethmoidal recess.

Dural Venous Sinuses

The dural venous sinuses are in the brain. The venous drainage of the brain begins as networks of small canals that drain into the larger vein, which then empty into the dural venous sinuses. These sinuses drain into the internal jugular veins. Of note, the diploic and emissary veins also drain into the venous sinus system.[4][5]

The superior sagittal sinus is at the superior border of the falx cerebri. It empties into the confluence of sinuses found posteriorly. It typically receives cerebral veins from the superior cerebral hemispheres and veins from the falx cerebri.

The inferior sagittal sinus is on the inferior border of the falx cerebri. As it ends posteriorly at the tentorium cerebelli, the great cerebral veins join it and become the straight sinus. The straight sinus runs along the falx cerebri and tentorium cerebelli before ending at the confluence of sinuses. The straight sinus usually receives blood from the posterior segments of the cerebral hemisphere surfaces, deep areas of the cerebral hemispheres via the great cerebral vein, superior cerebellar veins, and the falx cerebri.

The cavernous sinuses receive blood from the cerebral veins as well as the ophthalmic veins and emissary veins. The cavernous sinus has several structures that pass through it. They are the internal carotid artery and the abducens nerve (cranial nerve VI). Cranial nerves III, IV, V1, V2, or oculomotor, trochlear, ophthalmic, and maxillary nerves pass through the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus.

Embryology

Paranasal Sinuses

The ethmoidal and maxillary paranasal sinuses are very small in size but present at birth, while the sphenoid and frontal are both absent. The frontal sinus begins to form as early as 2-years old, but are nonidentifiable by radiology until around 6-years old.[6] All paranasal sinuses enlarge as a person ages, particularly at puberty and when the permanent teeth erupt.

Dural Venous Sinuses

The dural venous sinuses are present in a rudimentary form during infancy. They develop their adult shape in the months following birth. The primitive venous sinuses are plexiform and can quickly change due to the rapid growth of the cerebrum.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Paranasal Sinuses

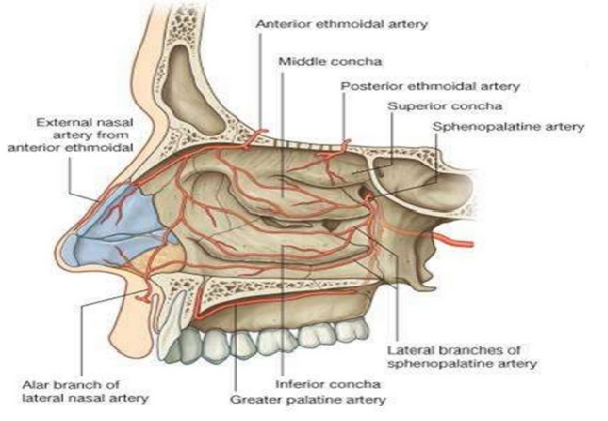

The anterior and posterior ethmoidal branches of the ophthalmic artery supply the ethmoidal and frontal sinuses. The infraorbital artery and the superior, anterior, and posterior alveolar branches of the maxillary artery supply the mucosa of the maxillary sinus. The pharyngeal branch of the maxillary artery supplies the sphenoidal sinus.

Nerves

Paranasal Sinuses

The nerves that supply the ethmoidal sinuses are the anterior and posterior ethmoidal branches of the nasociliary nerve. The nasociliary nerve is supplied by the V1 branch (ophthalmic nerve) of the trigeminal nerve. Orbital branches of the V2 branch (maxillary nerve) of the trigeminal nerve via the pterygopalatine ganglion also innervate the ethmoidal air cells. The maxillary sinuses receive innervation from the maxillary nerve via the infra-orbital and alveolar branches. The frontal sinuses receive innervation by the supraorbital nerve, a branch of V1 (ophthalmic) nerve. The sphenoidal sinuses get their innervation from the posterior ethmoidal branch of V1 (ophthalmic) nerve as well as orbital branches of the V2 (maxillary) nerve.[7][8]

Dural Venous Sinuses

One of the most prominent dural sinuses of the head is the cavernous sinus. This sinus is responsible for allowing the passage of many cranial nerves (CN), particularly important for ocular and facial function. These nerves are CN III (oculomotor nerve for ocular muscle innervation, lens accommodation, and pupillary constriction), CN IV (trochlear nerve for superior oblique muscle innervation), CN V (V1 and V2 segments for ocular and facial sensation) and CN VI (lateral rectus innervation).[9] Pathologies that affect the cavernous sinus such as infection, masses, or trauma can cause nerve damage resulting in cranial nerve palsies and decreased function.[10]

Physiologic Variants

Paranasal Sinuses

Asymmetry and absence of the paranasal sinuses are common. However, the absence of the maxillary sinus occurs infrequently and very rarely bilateral. Failure of fusion of the two ossification centers of the sphenoidal sinus can give rise to a “craniopharyngeal canal.”

Surgical Considerations

Paranasal Sinuses

The advent of endoscopic sinus surgery has increased the interest in the taxonomy of the internal nose and paranasal sinuses. Therefore, the names used by anatomists and surgeons differ at times. Anatomists use the Terminologia Anatomica. Lund et al. defined terms commonly used in surgical practice.

The location of the sphenoidal sinuses provides a convenient pathway to access the pituitary gland in its hypophyseal fossa surgically. The thin bones that line the sphenoidal sinus allow the surgeon to penetrate the roof of the nasal cavity, go through the sphenoidal sinus and enter the hypophyseal fossa.

Dural Venous Sinuses

Dural venous injury occurs approximately 1% to 4% in the general population. Mortality due to this injury is significant (41% overall and 20% during surgery).[11] The most common sinus injured is the superior sagittal sinus. A linear skull fracture can also occur that crosses a venous sinus, which typically causes significant bleeding that is difficult to control with simple digital pressure.

Clinical Significance

Paranasal Sinuses

When there is facial trauma, the paranasal sinuses can act as a “crumple zone” protecting the more delicate structures of the brain from injury.[12]

Dural Venous Sinuses

The emissary veins, which traverse the cranium and enter the dural venous sinus system, are a pathway that infection can enter the brain. This phenomenon is possible because the emissary veins have no valves. Emissary veins from the pterygoid plexus in the infratemporal fossa and ophthalmic veins from the orbit also pass through the cavernous sinus and can be a source of infection. In each case, infection is possible because the veins begin extracranially and become intracranial.[9]

Subdural hematomas typically result from injury to cerebral veins where they enter the superior sagittal sinus, which occurs because the cerebral veins are more mobile than the dura-encased sinuses. This type of intracranial hemorrhage occurs between the dura mater and arachnoid mater, layers of the lining of the brain. A subdural hematoma can occur from the most trivial injury.