Introduction

The anatomy of the head and neck is complicated due to the sheer number of fine structures in that region and many of which have variable depth and course. From a clinical standpoint, the head and neck maintain several critical neurovascular structures that have essential functions and potential disastrous surgical consequences if violated. The neck subdivides into smaller regions, zones, and compartments to help with maintaining the organization of this highly complex area. The two primary regions of the neck are the anterior and posterior triangles whose borders are defined by readily identifiable anatomic structures. These triangles are found deep to the skin, subcutaneous tissue, superficial cervical fascia, and platysma muscle and span the entire length of the neck. Within these triangles, muscles, nerves, blood vessels, lymphatics, and adipose tissue are present. The focus of this activity will be to describe the anatomy of the posterior cervical region, including the posterior triangle of the neck, and to relate the anatomy to important clinical considerations.

Structure and Function

Anatomic Boundaries

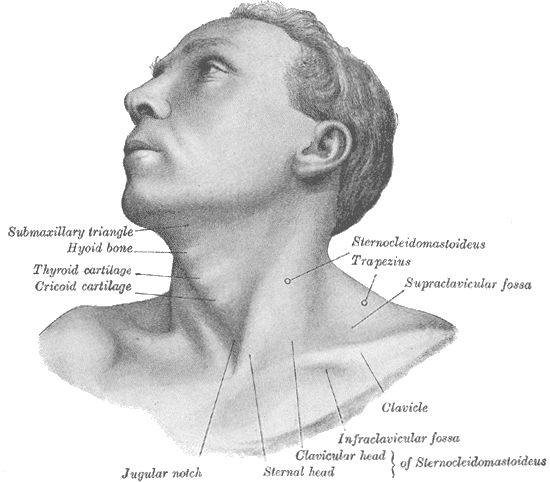

The posterior triangle of the neck occupies the posterior cervical region. The posterior triangle refers to a bilateral anatomic region that is on the posterolateral aspect of the neck. Distinct anatomic borders define the posterior triangle of the neck. The anterior border forms by the posterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The anterior border of the trapezius delineates the posterior border. The union of the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles at the superior nuchal line of the occipital bone forms the apex of the posterior triangle. The inferior boundary, which forms the base of the posterior triangle, is defined by the superior aspect of the middle one-third of the clavicle.[1]

The posterior triangle of the neck can further divide into two smaller triangles by the inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle. The omohyoid muscle consists of a superior and an inferior muscle belly joined by an intermediate tendon. The intermediate tendon is located just posteriorly to the inferior attachment of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The superior muscle belly spans from the body of the hyoid bone to the intermediate tendon and can't in the anterior triangle of the neck. The inferior belly originates at the lateral end of the superior border of the scapula and inserts at the intermediate tendon. It is this inferior belly that is within the posterior triangle of the neck. Within the posterior triangle, the area superior to the omohyoid muscle is referred to as the occipital triangle, while the area inferior to the omohyoid is referred to as the subclavian triangle.[1]

The superficial border, or the "roof" of the posterior triangle of the neck, is composed of the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia. The deep cervical fascia subdivides into several distinct layers that further organize the structures of the neck. The investing layer of the deep cervical fascia surrounds the neck circumferentially. It can be found just deep to the superficial fascia, a sheet of loose connective tissue that contains the platysma muscle. The investing layer of the deep cervical fascia is composed of a single layer as it forms the roof of the posterior triangle. However, the fascial layer splits into two to enclose the sternocleidomastoid and infrahyoid muscles anteriorly and the trapezius muscle posteriorly, thereby "investing" the muscles. Several structures that originate deeper in the neck pierce through the investing layer of the deep fascia in the posterior triangle to reach more superficial structures, including the external jugular veins, and the transverse cervical, supraclavicular, lesser occipital, and greater auricular nerves.[2][3]

The deep border, or the "floor" of the posterior triangle of the neck, is formed by the prevertebral layer of the deep cervical fascia. The prevertebral layer surrounds the bony vertebrae and the deep, prevertebral muscles of the neck. The space between the investing layer and the prevertebral layer of the deep cervical fascia contains the contents of the posterior triangle of the neck.[2][3]

The function of the Posterior Cervical Region

The posterior cervical region houses the posterior triangle of the neck, which functions to organize the neck into discrete anatomical subdivisions. The muscles and fascial layers located in the cervical region form natural boundaries that organize the neck and its contents. As will be discussed in the upcoming sections, the posterior cervical region houses many additional structures, including muscles, nerves, blood vessels, and lymphatics.

Embryology

The pharyngeal apparatus is behind the formation of the structures of the head and neck. The pharyngeal apparatus is composed of six branchial arches that develop in a cranial to caudal direction. Each arch contains mesoderm and neural crest cells that form cartilage, nerves, fascia, and muscles. The arches are lined superficially by the branchial clefts, which are composed of ectodermal tissue. On their deep surface, the arches are lined by endodermal branchial pouches.[4]

The sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles, which cover a large area of the posterior cervical region and form the borders of the posterior triangle, develop from somites, and neural crest found just caudal to the sixth branchial arch. One case study cites a congenital absence of the posterior triangle that resulted due to the fusion of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius. This anomaly can be explained embryologically by the failure of the mesoderm of the sixth branchial arch to separate and ultimately degenerate.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood Vessels

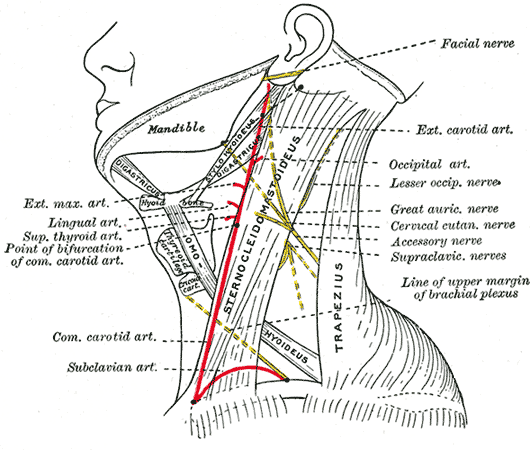

Posterior triangle vessels can be found in the subclavian triangle, inferior to the omohyoid muscle. The subclavian artery anatomically divides into three parts. The first part of the subclavian artery is the most proximal portion. The second part is the portion of the artery that passes posterior to the anterior scalene muscle. The third portion of the subclavian artery is the most distal portion and is contained within the posterior triangle of the neck once it emerges from behind the anterior scalene. As the subclavian artery continues distally and passes over the first rib, it becomes the axillary artery. The transverse cervical artery and the suprascapular artery are also contained within the subclavian triangle as they course anteriorly to the anterior scalene muscle. Both of these arteries are branches of the thyrocervical trunk, which is a major branch of the first part of the subclavian artery that arises immediately medial to the anterior scalene muscle. The subclavian, transverse cervical and suprascapular veins each accompany their respective arteries through the posterior triangle as well. However, the subclavian vein passes anteriorly to the anterior scalene, unlike the subclavian artery. The external jugular vein runs superficial to the posterior triangle before it pierces the investing layer of the deep fascia to enter the posterior triangle and empty into the subclavian vein.[6]

Lymphatics

Several groups of lymph nodes are within the posterior cervical region. The supraclavicular lymph nodes are located along the superior border of the clavicle and are within the posterior triangle. The posterior cervical lymph nodes run along the external jugular vein and are also present within the posterior triangle. The superficial cervical lymph nodes lie along the anterior surface of the sternocleidomastoid, while the deep cervical lymph nodes lie along the posterior surface of the sternocleidomastoid. Both the posterior auricular and occipital lymph node groups are near the apex of the posterior triangle, superficial to the superior portions of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles, respectively.[7]

The union of the lymphatic system and circulatory system also occurs in the proximity of the posterior cervical region. On the right side of the body, the right lymphatic duct empties into the junction of the right internal jugular and right subclavian veins. This vessel drains lymph from the right side of the head and neck, the right upper extremity, and the right hemithorax. The thoracic duct drains the lymph from the rest of the body. The thoracic duct empties into the junction of the left internal jugular and left subclavian veins.[8]

Nerves

The eleventh cranial nerve, also known as the spinal accessory nerve, provides motor innervation to both the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. After it exits from the skull through the jugular foramen, the accessory nerve runs along the deep surface of the sternocleidomastoid. It descends through the posterior triangle in an oblique direction. The accessory nerve is enclosed in investing fascia as it crosses the triangle and continues to the deep surface of the trapezius.[9]

The superficial branches of the cervical plexus that supply cutaneous sensation to the skin overlying the cervical region emerge from the posterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle near its midpoint, at a site known as the nerve point of the neck. The anterior rami of the spinal nerves pierce the investing fascia and split to form four cutaneous nerves that run deep to the platysma. The lesser occipital nerve forms from the second cervical spinal nerve and ascends posterior to the sternocleidomastoid to innervate the skin of the scalp and neck posterior to the ear. The greater auricular nerve forms from the second and third cervical spinal nerves and ascends on the anterior surface of the sternocleidomastoid to innervate the skin over the mastoid and parotid region inferior to the ear. The transverse cervical nerve forms from the second and third cervical spinal nerves and crosses horizontally over the sternocleidomastoid to innervate the anterior aspect of the neck. The supraclavicular nerve forms from the third and fourth cervical spinal nerves and descends across the surface of the investing fascia over the posterior triangle as it branches widely to innervate the skin over the clavicle and first two ribs.[10]

The phrenic nerve can be found deep to the posterior triangle within the prevertebral fascia as it runs along the anterior surface of the anterior scalene muscle. The spinal nerves of the fifth cervical vertebra through the first thoracic vertebra form the roots and trunks of the brachial plexus, which can also appear within the prevertebral fascia between the anterior and middle scale muscles.[11]

Muscles

The largest muscles of the posterior cervical region are the sternocleidomastoid and the trapezius. The margins of these muscles form the anterior and posterior borders of the posterior triangle, respectively. The sternocleidomastoid muscle originates at the anterior surface of the manubrium and the medial one-third of the clavicle. It inserts at the mastoid process and lateral aspect of the superior nuchal line. The action of the sternocleidomastoid is the contralateral rotation of the head and ipsilateral flexion of the neck. The trapezius is a broad muscle that has an extensive origin from the superior nuchal line and the spinous processes of cervical vertebra II through thoracic vertebra II. It inserts on the posterior aspect of the lateral one-third of the clavicle, the acromion, and the spine of the scapula. The action of the trapezius is to elevate, adduct, and depress the scapula. It also assists in the rotation of the scapula during arm abduction above the horizontal.[12][13]There is only one muscle located within the true boundaries of the posterior triangle, the inferior belly of the omohyoid. This muscle passes through the triangle in an anterior to posterior direction about 2.5 cm above the clavicle and can further subdivide the large posterior triangle into the smaller occipital and subclavian triangles. The omohyoid muscle is wrapped in a layer of fascia called the infrahyoid layer of the pretracheal fascia. The infrahyoid fascia is another component of the deep cervical fascia, in addition to the investing layer and prevertebral layer.[1] There are several more posterior cervical muscles located just deep to the posterior triangle that are ensheathed by the prevertebral layer of deep cervical fascia, known as the prevertebral muscles. Because this fascial layer composes the deep border of the posterior triangle, these muscles can also be considered the floor of the posterior triangle. These muscles include the anterior, middle, and posterior scalenes and the levator scapulae.[2][3]

Physiologic Variants

There exists some degree of variation among the anatomy of the posterior cervical region of different individuals, most notably involving the nerve point of the neck. The final destinations of the cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus are relatively predictable, but there is significant variability in their origins.[10] Once the spinal nerve pierces the investing layer of the deep fascia, it branches to form its four cutaneous branches. However, this branch point is often unpredictable. The nerve may split before emerging from the investing fascia so that anywhere from one to four cutaneous nerves pierce the investing fascia individually. It is also possible that the transverse cervical and suprascapular nerves travel together for a greater distance before splitting, while the same is true of the lesser occipital and posterior auricular nerves.

Surgical Considerations

The anatomy of the posterior cervical region has several relevant surgical implications. For example, the cutaneous nerves of the cervical plexus can be anesthetized using a superficial cervical plexus block. In this procedure, the anesthetist inserts a needle along the posterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid, through the skin and platysma. The local anesthetic gets injected near the site where the nerves emerge from the investing fascia. This technique frequently also affects the phrenic nerve, so superficial cervical plexus block is typically avoided in patients with any respiratory comorbidities, such as COPD. The superficial cervical plexus block is often done bilaterally and is performable with or without ultrasound guidance. It provides particularly useful pain control for thyroidectomy, parathyroidectomy, and carotid endarterectomy.[14]

Another method of anesthesia that involves the posterior cervical region is an interscalene block. This procedure targets the roots and trunks of the brachial plexus to provide local anesthesia for orthopedic procedures involving the clavicle or humerus. To perform an interscalene block, the anesthetist typically inserts the needle posterior to the clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid, through the prevertebral fascia, and into the interscalene groove. This procedure is accomplished using ultrasound guidance to locate the superior, middle, and inferior trunks of the brachial plexus. The trunks are visible as hollow circles on ultrasound organized in a "stoplight" pattern.[15][11]

It is also important to understand that many major structures are susceptible to incidental injury during surgery of the posterior cervical region, including the accessory nerve. To minimize the risk of injury, the accessory nerve can be directly stimulated intraoperatively to map its course and innervation territory.[16] This mapping allows the surgeon to visualize the path of the nerve better and avoid any potential intraoperative damage.

Clinical Significance

Cervical lymphadenopathy is a common presentation of various disease processes. A lymph node may become enlarged for a variety of reasons, and a physical exam is essential to determine the etiology of the lymphadenopathy. Soft, tender lymph nodes typically result from acute inflammatory processes, such as infectious mononucleosis or streptococcal pharyngitis. Large, firm, rubbery lymph nodes are often due to a more chronic condition, such as lymphoma.[17]

Another point of clinical relevance involving the posterior cervical region is an injury to the nerves of the posterior triangle. Injury to the accessory nerve can result in difficulty shrugging the shoulder or elevating the arm above the head because the trapezius muscle is compromised. If the accessory nerve suffers damage within the posterior triangle, the sternocleidomastoid muscle is spared because the accessory nerve already gives its motor branches to this muscle more proximally.[18] The cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus are also susceptible to injury from both trauma and iatrogenic causes and can result in sensory deficits over the cervical region. The particular nerve that is injured is identifiable by understanding the sensory distribution of the cervical plexus.