Introduction

The metatarsal bones are the bones of the forefoot that connect the distal aspects of the cuneiform (medial, intermediate and lateral) bones and cuboid bone to the base of the five phalanges of the foot. There are five metatarsal bones, numbered one to five from the hallux (great toe) to the small toe. The metatarsal bones are an essential structure for the origin and insertion of many muscles of the lower limb and foot and contribute to the proximal half of the metatarsophalangeal joints. Several pathologies involve the metatarsal bones, including fracture, dislocation, congenital and acquired abnormalities, as well as degenerative conditions that will be discussed in this paper.

Structure and Function

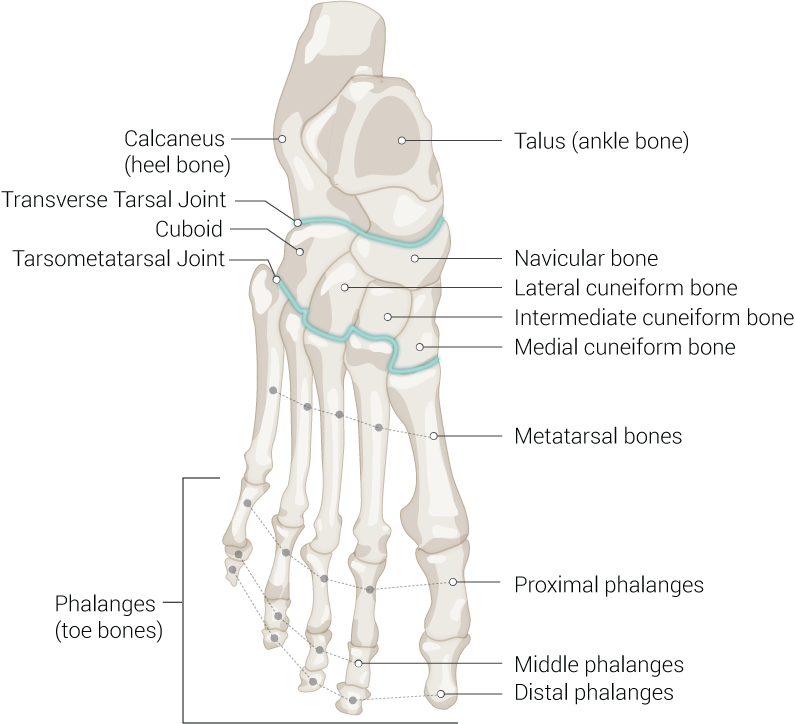

The five metatarsal bones are numbered from one through five, medially to laterally, starting at the hallux (great toe). Each of the metatarsal bones articulates proximally with a tarsal bone and distally to one of the five phalanges of the foot, making the metatarsophalangeal (TMP) joint. The proximal connection of the metatarsal bones and tarsal bones make up the tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint complex, commonly referred to as Lisfranc’s joint. Injury and disruption of the articulation between the medial cuneiform and the second metatarsal base is commonly known as Lisfranc injury.

The TMT joint complex can divide into a medial, middle, and lateral column. The first column includes the first metatarsal and the medial cuneiform. The first metatarsal is the shortest and widest metatarsal and articulates with the medial cuneiform bone proximally and the proximal phalanx of the hallux distally. The middle column of the TMT joint complex is composed of the second and third metatarsals and intermediate and lateral cuneiforms, respectively. The second metatarsal is the longest of the metatarsal bones and articulates with the intermediate cuneiform, while the third metatarsal articulates with the lateral cuneiform. The lateral compartment of the TMT joint complex is composed of the fourth and fifth metatarsals and the cuboid. Two sesamoid bones are associated with the medial column, located plantar to the first metatarsal head within the flexor hallucis brevis tendon. The hallux sesamoid bones are one of three locations of sesamoid bones in the human body in addition to the hand and the patella.[1]

The metatarsals are an essential insertion and origination site for many of the muscles of the lower limb and foot. The specific insertions of each of the muscles on the metatarsals appear below:

- Insertions:

- First metatarsal: peroneus longus, tibialis anterior

- Second metatarsal: tibialis posterior

- Third metatarsal: tibialis posterior

- Fourth metatarsal: tibialis posterior

- Fifth metatarsal: peroneus brevis, fibularis tertius, opponens digiti minimi

- Origins:

- First metatarsal: None

- Second metatarsal: adductor hallucis (oblique head), dorsal interossei

- Third metatarsal: adductor hallucis (oblique head), plantar interossei, dorsal interossei

- Fourth metatarsal: adductor hallucis (oblique head), plantar interossei, dorsal interossei

- Fifth metatarsal: peroneus brevis, plantar interossei, dorsal interossei

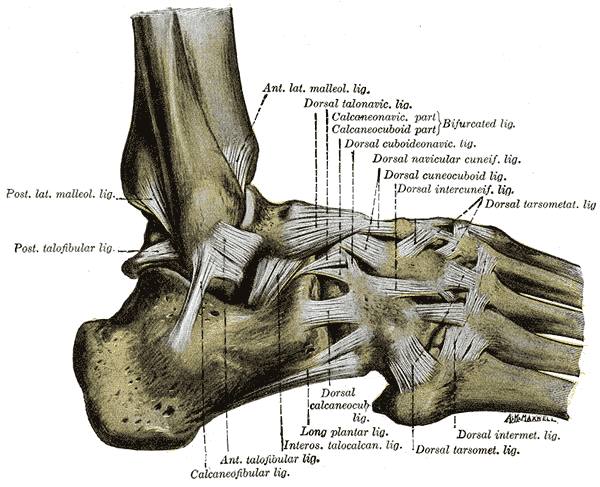

In addition to being an insertion site for many of the muscles of the lower limb and foot, the metatarsals are an important component of the arches of the foot. The arches of the foot function in force absorption, support, and as a rigid lever during gait propulsion. [2] There are three main arches: medial longitudinal arch, lateral longitudinal arch, and transverse arch. The medial longitudinal arch forms from the first three metatarsals, their respective tarsal articulating bones, and calcaneus. The lateral longitudinal arch forms from the fourth and fifth metatarsal heads, cuboid and calcaneus. Lastly, the transverse arch results from all of the metatarsal heads, cuboids, and the three cuneiform bones. The arches receive support by musculotendinous units of the anterior and posterior leg, as well as intrinsic muscles and ligaments of the midfoot and hindfoot.

The metatarsals are vital to proper biomechanical gait as they form a major weight-bearing area distally at their heads. The first metatarsal bears about 30-50% of the weight during the gait cycle. Additionally, the first and fifth metatarsal and column complexes, are mobile, allowing of superior-inferior motion to adapt to uneven surfaces. The other metatarsals do generally not move in this regard as they are firmly fixed at their bases.[2]

Embryology

The limb buds of the embryo commence forming about five weeks after fertilization as the mesoderm migrates into the limb bud and forms an anterior, posterior condensation and lateral condensation to eventually form the muscular and skeletal components of the lower limb.[3][4][5] The main contribution to the skeletal component of the lower limb is the lateral plate mesoderm, which will form the ilium, ischium, pubis, femur, tibia, fibula, tarsals, metatarsals, and phalanges. The lateral condensation chondrifies to form hyaline cartilage over weeks 6 to 7 and begins to form primary ossification centers by week 9, which continue to develop until birth.[3][4][5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply of the foot is provided by two main arteries, the anterior tibial artery, and the posterior tibial artery. The anterior tibial artery runs distally. It terminates at the anterior ankle midway between the lateral and medial malleoli, where it divides into the dorsalis pedis and the lateral tarsal artery. The dorsalis pedis artery continues distally between the extensor hallucis longus and extensor digitorum longus tendons, where its pulse is often palpated as part of the clinical physical exam. The dorsalis pedis artery and lateral tarsal arteries form an anastomosis, which gives rise to the dorsal metatarsal arteries. The dorsalis pedis artery terminates as the deep plantar artery.

The posterior tibial artery gives rise to the medial and lateral plantar arteries, which anastomose to form the deep plantar arch. The dorsalis pedis artery gives rise to the deep plantar artery, which communicates with the deep plantar arch forming an anastomosis between the anterior tibial and posterior tibial arteries.

The lymphatic vessels of the lower limb divide into two major groups—superficial and deep vessels. The superficial lymph vessels of the lower limb can further categorize into two groups: a medial group, which follows the greater saphenous vein, and a lateral group, which follows the small saphenous vein.[3] There are also deep lymph vessels, including the anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and peroneal vessels that follow the course of the corresponding blood vessels.[3] The lymph vessels of the lower limb drain into the popliteal, superficial inguinal, deep inguinal, external iliac and lumbar or aortic lymph nodes.[3]

Nerves

The tibial nerve branches to the two major nerves of the plantar foot: the medial and lateral plantar nerves. The medial plantar nerve supplies the first lumbrical, abductor hallucis, flexor digitorum brevis, and flexor hallucis brevis. The lateral plantar nerve is also a branch of the tibial nerve and innervates all the foot muscles except the four mentioned above.

The dorsal foot consists of two muscles, including the extensor digitorum brevis and extensor hallucis brevis. Each of these receives supply from the deep peroneal nerve, a branch of the common peroneal nerve that also supplies all the muscles of the anterior compartment of the lower limb.

Surgical Considerations

The most commonly fractured metatarsal in adults is the fifth metatarsal. As mentioned in the clinical significance discussion, conservative treatment including protected weight-bearing in a stiff-soled shoe, boot, or cast or non-weight bearing for six to eight weeks is generally the treatment choice for Zone 1 injuries. However, for Zone 2 and Zone 3 fractures in elite or competitive athletes, surgery with intramedullary screw fixation is indicated to minimize the risk of nonunion and/or prolonged restriction from activity.[6][7]

Lisfranc injuries can be managed operatively through open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), primary arthrodesis of the involved tarsometatarsal joints, or by midfoot arthrodesis. An ORIF is indicated if there is evidence of instability. ORIF in Lisfranc injuries tends to have better outcomes in bony fracture-dislocations as opposed to strictly ligamentous injuries. A primary can be considered in cases of instability as an alternative to an ORIF and have demonstrated equivalent functional outcomes with a reduced rate of return to the operating room for hardware removal. Midfoot arthrodesis merits consideration if there are chronic Lisfranc injuries that have failed conservative therapy or in the setting of midfoot collapse.[8][9][10]

In severe cases of Frieberg’s disease, surgical intervention may be necessary. The surgical options include metatarsophalangeal arthrotomy with the removal of loose bodies, dorsal closing-wedge osteotomy, and DuVries arthroplasty (partial metatarsal head resection). The first option is rarely necessary, but the other options may be indicated if the disease involves more of the dorsal bone and cartilage or in later-stage disease.[11]

Clinical Significance

Metatarsal injuries are quite common with metatarsal fractures, stress fractures, and Lisfranc injuries among the most commonly documented. Below is a brief overview of clinical conditions involving the metatarsal bones.

Metatarsal fractures are among the most common injuries of the foot. In children, the most commonly fractured metatarsal is the first metatarsal, while the fifth metatarsal is the most common metatarsal fracture in adults. The two main mechanisms of metatarsal fractures are direct crush injuries and indirect rotational mechanisms. Indirect mechanisms are much more common than direct crush injuries and typically involve hindfoot inversion, forefoot adduction, or repetitive microtrauma. Patients present with pain over the associated border of the forefoot, pain, and limitation with weight-bearing and may resist foot eversion on physical exam. Manual palpation of the area of concern will elicit significant pain. The majority of metatarsal fractures heal with nonoperative management. Open fractures, displaced fractures, and multiple fractures of the central metatarsals are indications for surgical fixation. Malunion of metatarsal fractures may lead to transfer metatarsalgia, defined as forefoot pain resulting from forefoot dysfunction in another area.[6][7][12]

Fifth metatarsal fractures are the most common of the metatarsal fractures in adults. From proximal to distal, the fifth metatarsal can divide into boney segments; the tuberosity, base, shaft, neck, and head. Fractures of the fifth metatarsal classify according to fracture location, or zone. Fractures proximal to the fourth-fifth metatarsal articulation classify as a Zone 1 fracture, also known as a “pseudo-jones” fracture. Fractures at the meta-diaphyseal junction, involving the fourth-fifth metatarsal articulation are known as Zone 2 fractures or “Jones” fractures. Due to the vascular watershed area at this junction, Jones fractures are associated with an increased risk of nonunion, reported to result in nonunion in 15 to 30% of fractures. Zone 3 fractures are fractures distal to the fourth-fifth metatarsal articulation and may be the result of direct trauma or stress fracture in a patient with antecedent pain. On physical examination, the patient will have pain and swelling over the lateral border of the foot. Radiographs are often sufficient for appropriate diagnosis. Zone 1 injuries are treated nonoperatively in a hard-sole shoe or controlled ankle motion walking boot. Zone 2 and 3 injuries may be initially treated nonoperatively with non-weight bearing in a short leg splint, followed by short leg cast for 6 to 8 weeks. In elite or competitive athletes, Zone 2 may be treated with intramedullary screw fixation to reduce the risk of nonunion and expedite return to sport.[6][7]

Stress fractures of the metatarsal are not uncommon. Also known as fatigue fractures, multiple repetitive strain cycles lead to microfractures in the bone. If the repetitive loading continues, microfractures may occur faster than the bone can heal them, resulting in a complete fracture. Metatarsal stress fractures are one of the most common sites of stress fractures in the body, resulting in nearly half of all stress fractures. The treatment of stress fractures is usually conservative, involving a reduction of activity for six to twelve weeks and a hard-soled shoe or cast.[13]

Lisfranc injuries are characterized by the disruption of the articulation between the medial cuneiform and the base of the second metatarsal, a tarsometatarsal fracture-dislocation, disrupting the TMT joint complex. This type of injury most commonly occurs as the result of high energy trauma in the setting of a motor vehicle accident, fall from height, or athletic injury due to an axial load on a hyper-plantar flexed forefoot. Lisfranc injuries can be managed nonoperatively through cast immobilization when there is no displacement on weight-bearing or stress radiographs or no evidence of bony injuries on CT. Often, Lisfranc injuries are treated operatively with open reduction internal fixation or, more commonly, primary arthrodesis of involved metatarsal joints. Recent studies indicate primary arthrodesis results in decreased rates of revision surgery or hardware removal with equivalent functional outcomes.[8][9][10]

Lastly, Freiberg disease is a rare condition characterized by infarction and fracture of the metatarsal head. Frieberg disease or infarction is believed to result from disruption of the blood supply in the setting of microtrauma or osteonecrosis, leading to collapse. This presentation is most common in adolescent female athletes involving the dorsal aspect of the second metatarsal head. Treatment can be nonoperative with activity limitations, NSAIDs, and immobilization with a short cast or stiff-soled shoe for four to six weeks in the early stages of the disease. However, in more severe cases, surgical intervention may be required.[11]