Introduction

Within the thoracic cavity, the lungs are separated from the thoracic wall by the visceral and parietal pleurae. Between these two layers exists a potential space called the pleural cavity. It is clinically significant, as pathologic processes can result in fluid accumulations within this space. The pleural cavity also maintains a negative intrapleural pressure, which resists the lungs’ natural tendency to collapse and facilitates proper function during respiration.

Structure and Function

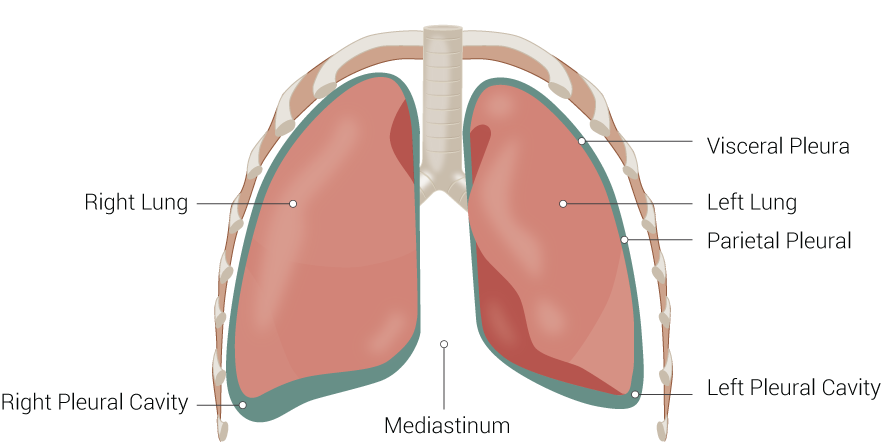

The pleurae are paired linings, located within the thoracic cavity, that surround each lung and separate them from the thoracic wall. They reflect upon themselves to form two layers of thin, serous membranes that glisten and appear grayish-yellow in color. A potential space called the pleural cavity forms between these layers. In a healthy individual, there is a small amount of fluid within this space. The layer of pleura that covers the lung parenchyma is named the visceral pleura. By invaginating and folding back on itself to form the fissures of the lungs, it is responsible for creating the different lung lobes. Opposite to the visceral pleura is the parietal pleura. This layer lines the diaphragm and thoracic wall.

At the root of the lung, the visceral and parietal layers are continuous, forming the hilum. The parietal pleura can be further subdivided based upon its region of approximation. The cervical pleura extends into the root of the neck. The costal pleura is adjacent to the ribs and intercostal spaces. The mediastinal and diaphragmatic pleurae cover the mediastinum and diaphragm, respectively.

During quiet respiration, the visceral and parietal pleura separate in regions that are not occupied by the lungs, resulting in pleural recesses. These allow for expansion during forced respiration. The costomediastinal recess is located anteriorly where the costal and mediastinal pleura meet. The costodiaphragmatic recess is the most clinically important, as most fluid collections pool here.

The pleural cavity always maintains a negative pressure. During inspiration, its volume expands, and the intrapleural pressure drops. This pressure drop decreases the intrapulmonary pressure as well, expanding the lungs and pulling more air into them. During expiration, this process reverses. The negative pressure of the pleural cavity acts as a suction to keep the lungs from collapsing. Damage to the pleura could disrupt this system, resulting in a pneumothorax.

Embryology

The visceral and parietal pleura derive from the splanchnic and somatic mesoderm, respectively. The pleural cavity develops between the fourth and seventh weeks of gestation, during which the lung buds expand to contact and fuse with the visceral pleura.[1] By the end of the third month, the lung buds are pushed fully into and are invaginated by the visceral pleura, completing the formation of the pleural cavity.[2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The bronchial arteries predominantly supply the visceral pleura. Blood returns to the heart via the pulmonary system. The parietal pleura, however, receives supply by the systemic arteries that overlie it (internal thoracic, intercostal, and phrenic arteries). Venous return for the parietal pleura occurs similarly.

Lymphatic drainage from the pleural cavity occurs through mostly parietal pleura involvement. The parietal pleura contains several openings (stomata) that allow fluid drainage to the subpleural lymphatic system. These drain to the diaphragmatic, internal mammary, retrosternal, paraesophageal, and celiac lymph node stations.[2]

The visceral pleura does have a significant role in draining fluid from the interstitium of the lung parenchyma. The lymphatic channels run through the basement membrane and mostly drain to the infralobar and hilar lymph nodes.[3]

Nerves

Historically, the parietal pleura was considered to be the only innervated part of the pleura. The intercostal nerves that run parallel to the ribs give off branches that innervate the costal pleura. Alternatively, the phrenic nerve is the primary innervation for the diaphragmatic and mediastinal pleurae.

There is a long convention that visceral pleura has no innervation and no role in pain. Interestingly, recent research has shown that the visceral pleura may be innervated by what researchers have referred to as visceral pleura receptors (VPRs) that may be associated with the elastic fibers of the lung. They may be involved in the reflexive dyspnea that is present in some pulmonary illnesses.[4]

Muscles

Muscles involved in the pleural cavity are typically associated with muscles of respiration. These include the diaphragm and intercostal muscles. Additional accessory muscles include the sternocleidomastoid and scalene muscles. The pectoralis major and minor can also help in forceful respiration.

Physiologic Variants

Both lungs contain an oblique fissure formed by the visceral pleura that creates the upper and lower lobes. Additionally, the right lung has a horizontal fissure splitting the right upper lobe from the right middle lobe. Multiple variants of this process exist, known as accessory fissures. The most common is the azygos fissure. Others include the inferior accessory, superior accessory, and left horizontal fissures.[5]

Surgical Considerations

Pneumothoraces are relatively common. They can occur with any injury to the pleural space that causes the negative intrapleural pressure to be lost. A small pneumothorax may be asymptomatic; however, a large pneumothorax typically presents with symptoms like chest pain and shortness of breath. The physical exam will be remarkable for a hyper-resonant hemithorax without breath sounds. A pneumothorax typically classifies as either spontaneous (classically young, tall, male smokers) or traumatic (lung biopsy, central line insertion, penetrating chest trauma).

Specifically, the parietal pleura incur damage during central line placement. The patient is at more risk when access is through the subclavian vein than the internal jugular vein. Regardless, a post-procedure chest radiograph is mandatory to ensure that a pneumothorax has not developed. Similarly, a post-procedural radiograph is necessary after performing lung biopsies.

Observation with serial chest radiographs is usually all that is required for small pneumothoraces. However, if the pneumothorax is large and symptomatic, insertion of a chest tube may be necessary.

Clinical Significance

Pleural effusions are collections of excess fluid within the pleural space. They are generally categorized as either transudative or exudative as determined by thoracentesis and fluid analysis. The Light’s Criteria is commonly used to identify an exudate. This tool compares the protein and lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) concentrations in the aspirated pleural fluid to the concentration of these products in the patient's serum.

Light's Criteria:

- A ratio of protein in the pleural fluid to protein in the serum over 0.5

- A ratio of pleural fluid LDH to LDH in the serum over 0.6

- Pleural fluid LDH greater than two-thirds the upper limit of normal for serum LDH set by each laboratory

If one of the preceding criteria is met, the fluid is considered to be an exudate and further workup is likely required.

Transudative effusions are usually secondary to disruptions in hydrostatic and oncotic pressures in the chest such as those that can occur with congestive heart failure and nephrotic syndrome. Exudative effusions have a larger differential. Some etiologies include infectious or noninfectious inflammation, malignancies, lymphatic drainage abnormalities, and many others.

Aside from being used for diagnosing the origin of the effusion, a thoracentesis is used therapeutically to drain fluid from the pleural cavity.

Pleural tumors are not uncommon. They are more likely malignant than benign. The most common malignant tumors include metastases, malignant mesotheliomas, and lymphomas. The most common benign tumors include solitary fibrous tumors and lipomas.[6]