Introduction

The bones of the pelvis are a critical part of the central portion of the skeleton. They serve as a transition from the axial skeleton and the appendicular skeleton of the lower body, serving as an attachment point for some of the strongest muscles in the human body while withstanding the forces generated by them. The curved nature of the pelvic bone creates a closed structure, itself lined with various muscles and housing various blood supplies, lymphatic structures, nerves, and organs, including the intestines, urinary bladder, and internal sex organs.

Structure and Function

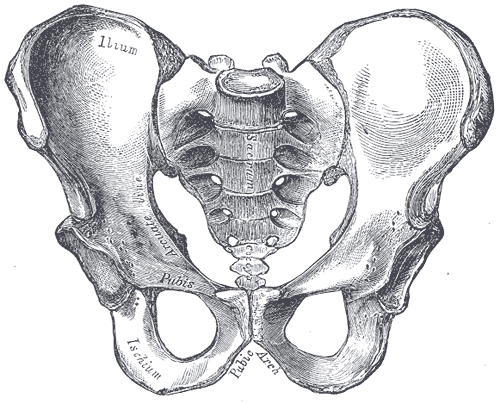

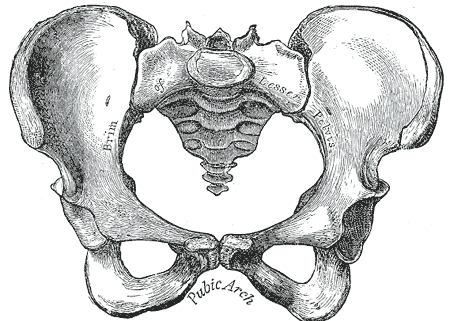

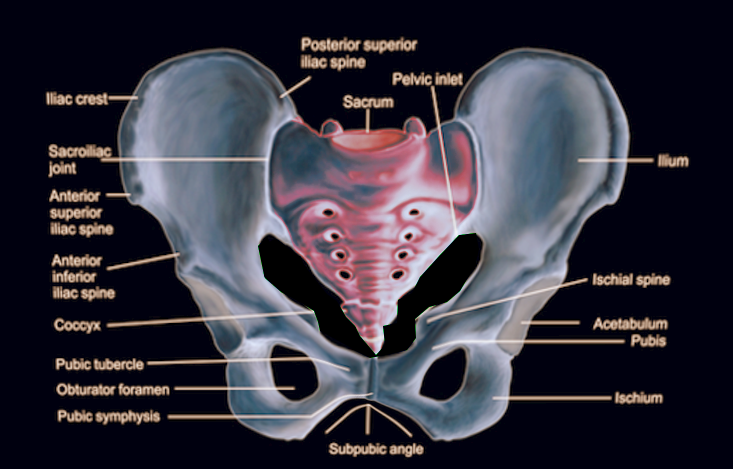

The pelvis is comprised of the large hip bone, the os coxae, on each side. The os coxae itself is composed of the ilium (the flat superior protuberance), ischium (the curved anterior protuberance), and pubis bones (the curved inferior protuberance). The os coxae attach anteriorly to each other at the pubic symphysis and posteriorly to each side of the sacrum, creating the sacroiliac joint. These three os coxae bones meet each other at the acetabulum, a medial structure that serves as an attachment point for the head of the femur. The pubis and ischium also articulate inferiorly at the ramal epiphyses, with their curving nature leaving an opening between them known as the obturator foramen. This foramen allows the obturator nerve to leave the pelvic cavity. Each of the pelvic bones also has many landmarks (i.e., tuberosities, notches) unique to the specific bone. The superior edge of the ilium is named the crest of the ilium, or, more commonly, the iliac crest, with a tuberosity below it on the ilium’s anterior edge known as the anterior inferior iliac spine. The ilium also has a posterior-inferior landmark known as the greater sciatic notch on it, with a subsequent lesser sciatic not being on the posterior-inferior side of the ischium. On the anterior side of the same edge of the ischium is the tuberosity of the ischium.[1][2]

The primary function of the pelvic bones is to transfer the load of the upper body onto the lower limbs while standing or walking. This function takes place through the connection of the axial and appendicular skeletons at the sacroiliac joint. When a man stands upright, the center of gravity lies in the center of the body. The pelvis transmits the weight to the femur and both lower extremities. The rigid structure of these bones also protects the organs that lie within their confinements. Such organs include the bladder, rectum, urethra, and uterus in females.[3]

Embryology

Pelvic bones begin their development as mesenchymal tissue of the embryonic lower limb buds. This mesenchyme begins extending out in three directions, corresponding to each of the three bones of the os coxae. The ischial and pubic masses migrate around the obturator nerve, fusing inferiorly to form the obturator foramen. Each pubic mass migrates medially to meet at the future pubic symphysis, while interactions with the primitive spinal column draw the iliac mass toward the sacrum derived from notochord mesenchyme. These mesenchymal masses then undergo endochondral ossification, with ilium, ischium, and pubis beginning primary ossification at third, fourth-to-fifth, and fifth-to-sixth months of gestation, respectively. Each bone’s primary center of ossification is near the future acetabulum, with the ossification process fanning out superiorly, inferiorly, and anteriorly in the direction of each bone. Sacral ossification begins in the third month, with each of the vertebrae having three centers of ossification. Secondary ossification occurs during the first year of life. Secondary ossification centers are at the articulation of the three pelvic bones in the acetabulum, the crest of the ilium, anterior inferior iliac spine, tuberosity of the ischium, symphysis pubis, and ramal epiphyses. These growth plates close during mid-puberty.[1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Many blood vessels are contained within the cavity created by the pelvic bones. These vessels include the common iliac artery, external and internal iliac artery, superior and inferior gluteal artery, obturator artery, superior vesical artery, and internal pudendal artery, along with their accompanying veins. Some of these arteries and their branches, such as the internal iliac, remain within the pelvic cavity while others travel out, such as the gluteals and external iliac, to supply regions such as the buttocks and lower limbs, respectively. The gonadal and uterine arteries will also run through and into the pelvic cavity, respectively, depending upon sex. Major lymph nodes in this region include the obturator, common iliac, external and internal iliac, hypogastric, superior rectal, presacral, presacral, promontory, and perirectal nodes. Nodes with the corresponding vasculature appear in pairs, one being on the anatomical left and the other on the anatomical right. Pelvic lymph nodes are a common site of prostatic and gynecologic cancer metastasis.[4][5][6][7]

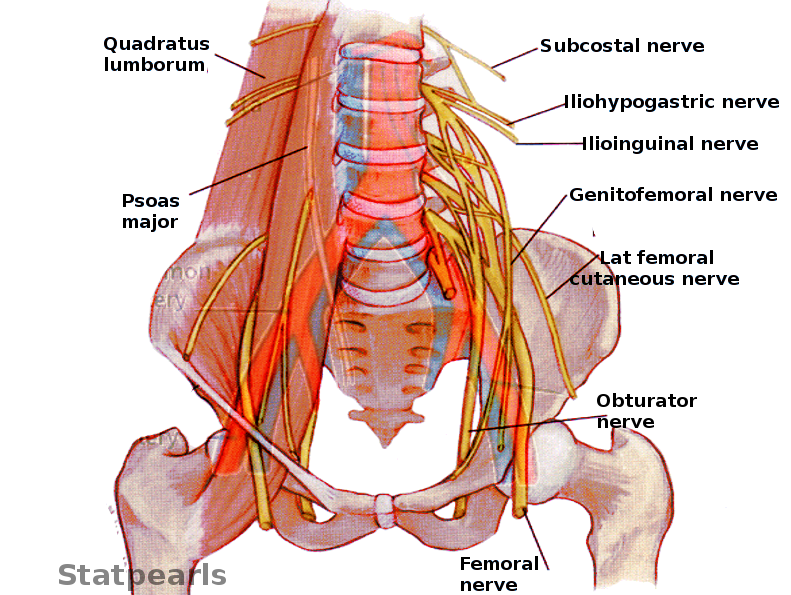

Nerves

The pelvic bones, and the girdle made by them, house nerves from the lumbar and sacral plexuses. Nerves of the lumbar plexus contained in the pelvis include the genitofemoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, obturator, and femoral nerves. The genitofemoral pierces through the psoas muscle posterior-to-anterior to reach the genital region on the anterior face of the pelvis. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve leaves the spine and transverses the pelvis exiting under the anterior brim of the crest of the ilium to reach the thigh. The obturator nerve descends medially to the psoas to leave the pelvis through the obturator foramen. The femoral nerve runs between the psoas and the iliacus, emerging from the pelvis above the pubis to continue into the anterior thigh.[2][8]

Sacral plexus nerves of the pelvis include the sciatic, superior, and inferior gluteal, posterior femoral, and pudendal nerves. The first four of these nerves all leave the pelvis traveling under the greater sciatic notch, serving innervations on the posterior gluteal and thigh regions. The superior gluteal nerve gives innervations to the gluteus minimus and medius, while the inferior gluteal innervated the gluteus maximus, which extends the hip. The pudendal nerve travels within the pelvic girdle, sending interventions to various sphincters and genitalia structures. This nerve commonly gets injured during the vaginal delivery of children.[9]

Muscles

The muscles around the pelvis are essential in maintaining the stability of the pelvic girdle, maintaining an erect posture, and assisting the movement of the trunk and lower extremities.

The internal iliac crest serves as the origin of the Iliacus muscle, which travels inferiorly and meets with the psoas, which originates above the pelvis but travels down through it, to make the iliopsoas. This muscle eventually exits the pelvis and inserts itself upon the femur. The piriformis is another muscle that originates inside of the pelvis and inserts externally on the femur.[10]

The pubic symphysis serves as an attachment point for both abdominal muscles, including the rectus abdominis, internal and external obliques, and transversus abdominis, as well as muscles of the adductor compartment of the leg, including the adductor brevis/longus/magnus, gracilis, and pectineus. Attached along the inferior edges of the pubis running posteriorly to the sacrum are the pelvic floor muscles, which include the puborectalis, iliococcygeal, ischiococcygeus, pubococcygeus, external anal sphincter muscles, and levator ani. The obturator internus muscles also have insertions on the internal side of the pubis and travel on the pelvic floor muscles, eventually leaving the greater sciatic notch and inserting on the posterior surface of the femur. The obturator externus travels from the anterior face of the pubis posteriorly to insert on the backside of the femur as well. The gluteal muscles, quadratus femoris, and semitendinosus muscles all also have attachments on the pelvic bones. The inguinal ligament, a common anatomical landmark involved with a hernia, runs from the anterior portion of the iliac spine to the front of the pubic symphysis.[11][12][13][14]

Physiologic Variants

The pelvis in females is very different from that of males; this is very important for females to provide an adequate birth canal for the large head of the fetus during birth. To achieve these means, the female pelvis is generally broader and shallower (gynecoid shape). The birth canal has to be rounded and more spacious. The sciatic notch is much wider with shorter symphysis pubis, and the pubic bones have a much broader angle with each other. The female coccyx is more mobile, and the sacrum is shorter and less curved.

Clinical Significance

A weakness of muscles of the pelvis, such as in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, will result in an abnormal waddling type of gait. A unilateral weakness of the hip abductor muscles or subluxation of a hip joint will cause a Trendelenburg gait. An analysis of how a patient walks can give clues to the underlying problems related to the structure and function of the pelvis.

Surgeries performed on pelvic structures may be complicated by excessive bleeding or hematoma formation. Surgery may also be complicated by infection and abscess formation. In the pelvis, hematoma or abscess usually remains localized in the retroperitoneal space just in front of the iliopsoas muscles. The presentation is often related to compression of the femoral plexus or the femoral nerve in the retroperitoneal space. The patient will present with postoperative weakness of the hip flexors and knee extensors with or without the involvement of the obturator muscles, depending on whether it is compression of the femoral plexus or the femoral nerve.

A female with a male type (android) of the pelvis will encounter problems during childbirth, which is one of the most prevalent indications for a caesarian section.[15]