Introduction

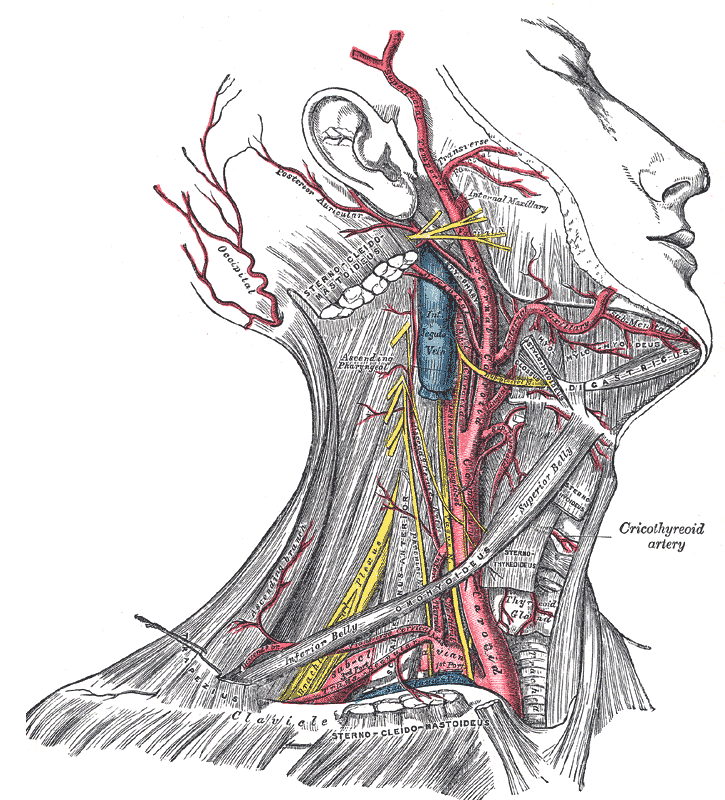

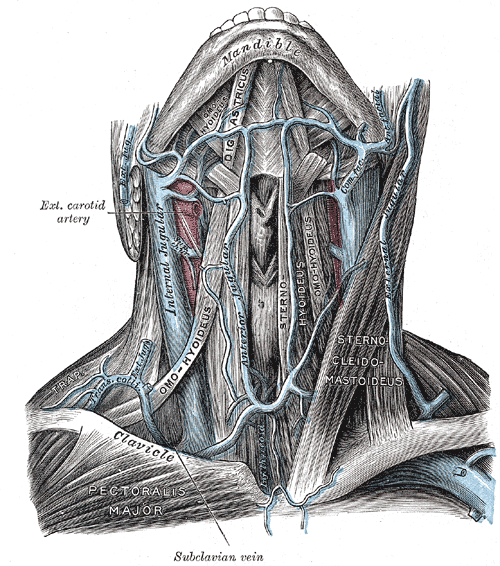

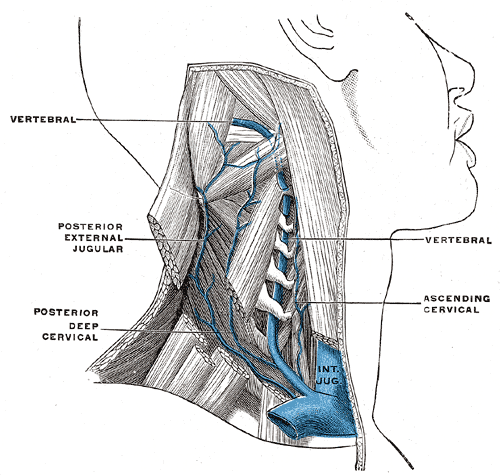

The internal jugular vein is a paired venous structure that collects blood from the brain, superficial regions of the face, and neck, and delivers it to the right atrium. The internal jugular vein is a run-off of the sigmoid sinus. It arises in the posterior cranial fossa and exits the cranium through the jugular foramen, located at the base of the skull. As the internal jugular vein runs down the lateral neck, it drains the branches of the facial, retromandibular, and the lingual veins. The course of the internal jugular vein is directed caudally in the carotid sheath, accompanied by the vagus nerve posteriorly and the common carotid artery anteromedially. It lies just lateral and anterior to the internal and common carotid arteries. At the junction of the neck and thorax, the internal jugular vein combines with the subclavian vein to form the brachiocephalic or innominate vein. The left internal jugular vein is slightly smaller than the right internal jugular vein. Both veins contain valves located a few centimeters before the vessels drain into the subclavian vein.[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

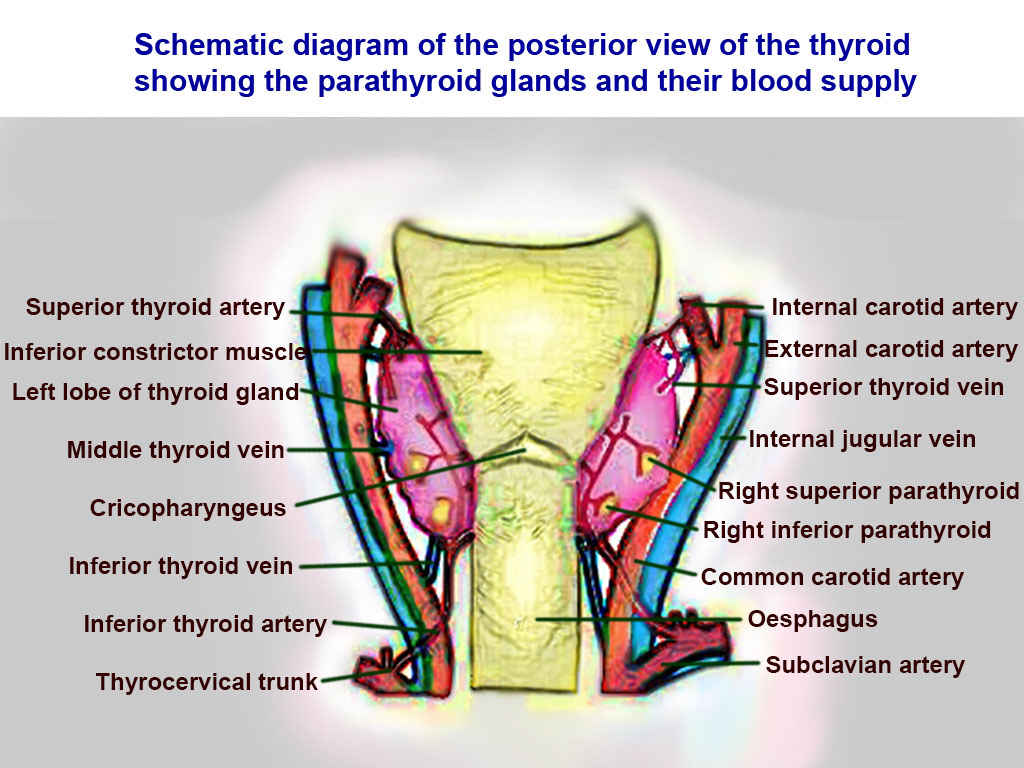

The function of the internal jugular vein is to collect blood from the skull, brain, superficial parts of the face, and the majority of the neck. The tributaries of the internal jugular include the inferior petrosal sinus, facial, lingual, pharyngeal, superior and middle thyroid, and, occasionally, the occipital vein. The blood collected from these vessels then drains to the brachiocephalic vein and into the right atrium.

Embryology

The earliest vessels of the cranium form a primordial hindbrain channel that drains into the precardinal vein. The cranial portion of the precardinal vein eventually forms the internal jugular vein.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Deep cervical lymph nodes lie along the internal jugular vein, mainly on its superficial surface. At the confluence of the left subclavian and internal jugular vein, lymphatics drain via the left thoracic duct. The left thoracic duct is responsible for draining lymph from below the diaphragm and the left half of the upper body.

Nerves

The cervical plexus and phrenic nerve lie posteriorly to the internal jugular vein as it exits the skull through the jugular foramen. The vagus nerve accompanies the internal jugular vein medially in the carotid sheath and lies between the artery and vein, but is slightly posterior. The loop of the ansa cervicalis also typically lies on the superficial lateral aspect of the internal jugular vein.

Muscles

The rectus capitis lateralis, levator scapulae, scalenus medius, and scalenus anterior all lie posteriorly to the internal jugular vein. The sternocleidomastoid muscle overlaps the internal jugular superficially. Additionally, the vein is crossed over by the posterior belly of the digastric and the superior belly of the omohyoid muscles. The sternocleidomastoid and infrahyoid muscles cover the internal jugular vein as it passes under the clavicle.

Physiologic Variants

Like many veins in the body, the internal jugular can have many anatomical variations. Some of the more clinically significant variations include a vein that is significantly smaller than expected or absent altogether.

Surgical Considerations

Central Venous Access (Internal Jugular Approach)[4]

The internal jugular vein is a preferred initial access site for a central venous catheter. Ultrasound (US) guidance is typically used for assessing cervical anatomy, patency of the vessel, the presence of a thrombus in the lumen, and the internal jugular veins relationship to the common carotid artery. The right internal jugular vein has a relatively straight course into the subclavian vein and right atrium. When cannulating the internal jugular without ultrasound guidance, the main external landmark is the division of the medial and lateral heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The patient is placed in Trendelenburg positioning with their head rotated away from the side of cannulation. Under ultrasound visualization, the skin above the internal jugular vein is anesthetized with lidocaine. A 16-gauge multipurpose introducer needle is introduced and directed inferiorly toward the ipsilateral nipple. Backward pressure should be applied to the syringe as the needle is advanced. Observe the needle puncture the anterior wall of the vein with ultrasound. Following cannulation of the vein, there should be dark red, non-pulsatile blood aspirated back into the syringe. The syringe is removed, and a guidewire advanced through the introducer needle about 5 to 10 cm. There should be no resistance felt during this step. If the patient is on telemetry, monitor the ECG for ectopy. The needle can be withdrawn over the guidewire, and a small skin incision is made using an 11-blade scalpel at its entry point. A dilator(s) is then advanced over the wire to create a subcutaneous tract. The dilator is removed, and the central venous catheter can advance over the wire. The guidewire is then withdrawn. Each port should be aspirated, noting adequate blood return, and then flushed with sterile saline. The catheter can then be sutured to the skin surface and dressed in a sterile fashion. A stat chest X-ray should undergo evaluation for appropriate placement of the catheter tip at the atriocaval junction and absence of the pneumothorax.[5][6][7]

Trauma

The jugular vein has a superficial course in the neck and has no protection from bone or cartilage. It is beneath the sternocleidomastoid muscle and easily prone to blunt or penetrating trauma. Injury to the vein can result in significant hemorrhage as well as a risk of air embolism. Digital compression is the simplest way to control bleeding from a lacerated internal jugular vein. Surgical exploration may be necessary. If possible, the internal jugular vein should be repaired, with care taken to limit narrowing the vessel. In severe cases, the internal jugular vein may require ligation. At the time of exploration, attention is also necessary to assess other structures such as the vagus nerve and carotid artery, as well as the nearby aerodigestive structures.

Clinical Significance

Jugular Venous Pressure

The internal jugular vein is widely used to assess the jugular venous pressure. One can roughly estimate the pressure in the right atrium by looking at the pulsations and their height in the internal jugular vein. For a professional to measure jugular venous pressure, the patient must be seated at 45 degrees with the head slightly turned to the contralateral side. Elevations of the jugular venous pressure may present in cardiac tamponade, tricuspid regurgitation, right heart failure, and tricuspid stenosis. When the jugular venous pressure is low, it usually signifies low blood volume or dehydration. An important thing to note is that the pulse in the jugular vein is not palpable. One can also raise the pressure in the jugular vein by applying manual pressure on the liver.

Cannulation

The internal jugular vein is used for cannulation since it is large, superficial in location, and usually does not vary in its course along the neck; this can be the preferred initial access site for central venous catheterization. The central line may be placed to monitor jugular venous pressure, administer fluids and medications, nutrition, or resuscitate a patient. The most common complication following placement of the internal jugular vein via the neck is a puncture of the carotid artery. Pneumothorax can occur if the needle is penetrated deep into the neck. However, the risk is lower when compared to subclavian access. In rare cases, the vagus nerve may also suffer injury.

Internal Jugular Vein Thrombosis[8][9]

Thrombosis of the internal jugular vein is usually iatrogenic as a result of an internal jugular central venous catheter. Recently, there has been an increased incidence due to intravenous drug users injecting directly into their internal jugular veins. The most common clinical manifestations of thrombosis include neck pain, fever, leukocytosis, and swelling. The swelling may also extend into the ipsilateral upper extremity. Urschel sign is occasionally appreciated in which there is distention in the lower neck and anterior chest veins as a result of the impedance of drainage from the internal jugular. Diagnosis is possible with venous duplex ultrasonography of the neck. US findings include incompressible vein, the presence of a clot, and no response to the Valsalva maneuver. Contrast CT may also assist with diagnosis. Sequelae of thrombosis can include an extension of the thrombus or pulmonary embolism. Therefore, internal jugular thrombosis is viewed as a deep vein thrombosis. Treatment for thrombosis may include a need for anticoagulation.

Lemierre Syndrome[10]

Internal jugular thrombosis as a result of pharyngeal infection is known as Lemierre syndrome. This condition can occur when a pharyngeal infection, such as an abscess, extends into the internal jugular vein. A deadly complication of this process includes an extension of septic thromboembolism into the lungs. Treatment is antibiotics and perhaps anticoagulation.

Other Issues

The jugular vein has significant clinical importance for physicians and nurses. It not only offers a way to monitor the fluid status of a patient but is a convenient method of administering fluids and medications. The jugular vein is often a site for cannulation for TPN, temporary hemodialysis, and administration of chemotherapeutic medications. Following the insertion of the cannula, the nurse is responsible for maintaining the site clean and observing for signs of infection.