Introduction

Scientists who sought to understand the spinal venous system thought of it as the fourth venous system, the other three systems being the portal, caval, and the pulmonary venous systems. The spinal venous system consists of a network of valveless veins grouped into three intercommunicating drainage systems that empty into extra spinal veins, ultimately returning venous blood to the heart. Since the system is valveless, spinal venous drainage is influenced by gravity, body position, intraabdominal, and intrathoracic pressure. Knowledge of this system equips clinicians to diagnose and treat pathology that results from its failure.[1]

Structure and Function

The spinal venous system consists of the intrinsic, extrinsic, and extradural systems. During IVC occlusion, the spinal venous system can serve as a collateral drainage system due to its connection with both pelvic and cranial veins.[1] During the collapse of the internal jugular vein in the upright position, venous drainage from the brain can be achieved via the vertebral veins, demonstrating its interconnectedness.[1] Veins of this system vary in their number and diameter, depending on their location along the cord.[2]

Embryology

The development of spinal cord veins begins around week 4 of gestation with the common cardinal vein, along with the right and left anterior and posterior cardinal veins. Paired supracardinal and subcardinal veins develop inferior to the common cardinal vein. Simultaneously, the paravertebral plexus forms around the developing spinal cord, and the cardinal veins connect to the paravertebral plexus via transverse intersegmental veins. Several transverse intersegmental veins form from the cardinal veins along its length. In the mature fetus, the transverse intersegmental veins in the cervical area become the vertebral veins, the right supracardinal vein persists as the azygos vein, and the left supracardinal becomes the hemiazygos and accessory hemiazygos veins. The anterior cardinal veins become the internal and external jugular veins, while the right posterior cardinal vein becomes the arch of the azygos in the mature fetus. With the regression of the cardinal veins, the paravertebral plexus drains into the ascending lumbar and azygos veins. Several anastomoses also form during development, and the azygos veins connect to the common iliac via the ascending lumbar and subcostal veins.[1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

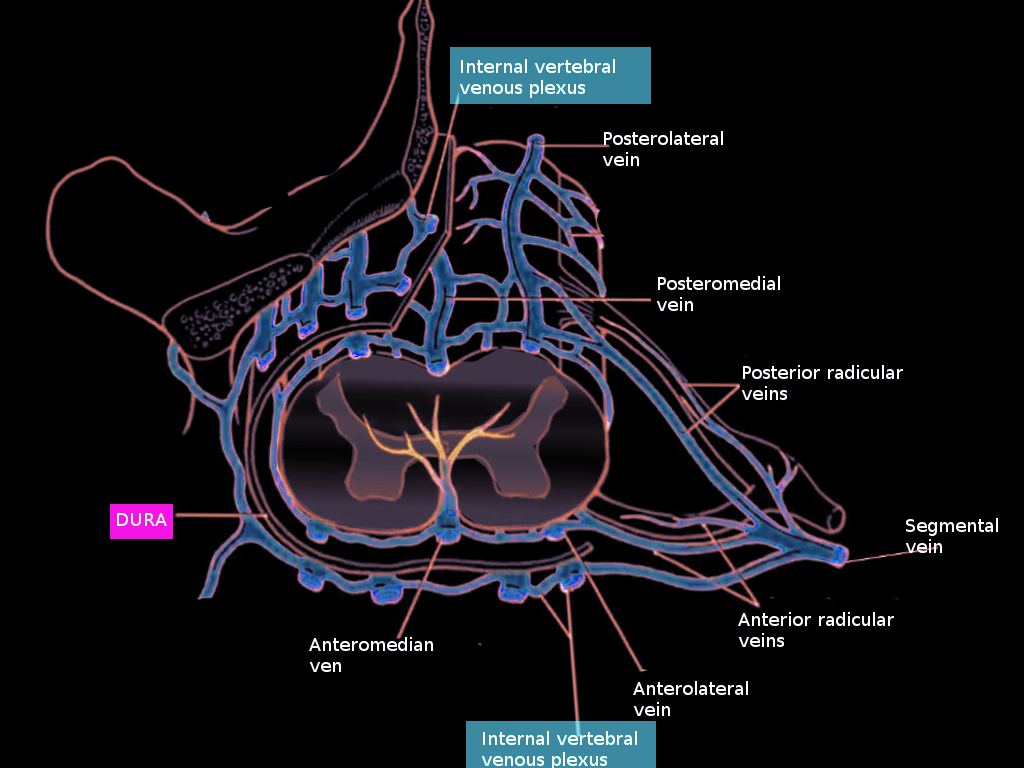

The intrinsic venous system refers to the collecting veins within the spinal cord parenchyma and further divides into central and peripheral drainage systems. In the central region of the cord, blood is drained centrifugally via numerous sulcal veins located both ventrally and dorsally. Ventral sulcal veins drain the medial portion of the anterior horn, the anterior commissure, and the white matter of the anterior funiculus.[1] The dorsal central veins drain the gray commissure and the white matter near the posterior median sulcus. The remaining areas of the cord are also drained centrifugally by peripheral radial veins.[3] Numerous anastomoses called transmedullary anastomotic veins link the radial and sulcal veins.[1] Blood from the sulcal veins empties into the anterior spinal vein, and blood from the radial veins drains into the posterior spinal veins.[2] Radial veins also form a venous ring at the surface of the spinal cord, which anastomoses with the anterior and posterior spinal veins as well as the pial plexus on the surface of the cord. These both belong to the extrinsic venous system.[3]

The pial venous network, radicular veins, as well as longitudinally oriented anterior and posterior spinal veins, comprise the extrinsic system of the spinal cord, which collects blood from radial and sulcal veins. The usually paired anterior spinal veins course from the medulla oblongata to the filum terminale. While the anterior spinal veins are typically in pairs in the cervical and thoracic regions, they become a single vessel in the lumbar area. It is located within the anteriomedian fissure and runs anteromedially, alongside the anterior spinal artery. The posterior median spinal vein begins at the conus medularis and can extend the length of the cord, usually within the posterior median fissure. It is often a single vessel but can be paired or even form a plexus.[3] Numerous ventral and dorsal radiculomedullary veins collect blood from the anterior and posterior spinal veins.[1] These veins course with the nerve roots without draining them.[3] The largest radiculomedullary vein, called the great anterior radiculomedullary vein (GARV), drains the thoracolumbar cord and can be mistaken for the artery of Adamkiewtz due to its size and common location.[1][2] Radiculomedullary veins exit the dura, usually with the nerve root. They are then joined farther distally by veins draining the nerve root, called superficial nerve root veins. Radiculomedullary veins then empty into the internal vertebral venous plexus of the extradural system.

The vertebral venous plexus, also called the Batson plexus refers to veins located extradurally within the spinal canal (internal plexus), surrounding the vertebral column (external plexus) as well as horizontal basivertebral veins that run through the vertebral bodies (basivertebral plexus).[1][2] These veins comprise the extradural spinal venous system and drain both the spinal cord and the vertebral column. The internal vertebral plexus is made up of two anterior longitudinal veins coursing on either side of the posterior longitudinal ligament and two posterior veins coursing anterior to the ligamentum flavum.[3] The internal plexus communicates with various intracranial venous plexus. Intervertebral veins link the external and internal vertebral venous plexus, and via segmental veins, drains blood into the extraspinal system.[2]

Intervertebral veins of the cervical cord empty into the vertebral, deep cervical, and jugular veins. Those of the thoracic cord drain into the hemiazygos and accessory hemiazygos veins on the left, and the azygos vein on the right. Intervertebral veins draining the lumbar region empty into the azygos and ascending lumbar veins.[1]

Nerves

Pathology within the spinal venous system can cause ischemic myelopathy via venous hemorrhage or venous obstruction.

- Venous hemorrhage directly into the cord can result from trauma or vascular malformations, and ultimately disrupts the normal functioning of the parenchyma. Intrathecal hypertension can result from cord hemorrhage with consequent venous engorgement and rupture of the internal vertebral venous plexus.[1]

- Venous occlusion due to emboli or thrombus from sepsis or malignancy or occlusion of the vertebral venous plexus during decompression sickness can also cause ischemic myelopathy.[3]

- Additionally, spinal stenosis and intervertebral disc herniation can cause radiculopathy via venous obstruction of radicular veins with consequent dilation of the veins and compression of nearby nerve roots.[1] Venous occlusion at the intervertebral foramen by a severely herniated disc can cause myelopathy via venous hypertension, albeit rare,[1][4] even in the absence of arteriovenous malformations. The herniated disc obstructs veins in the intervertebral foramen resulting in decreased venous return from the spinal parenchyma. [1] This causes venous congestion of the spinal cord since the veins are valveless. This congestion causes increase venous pressure and subsequent vasodilation of intramedullary arteries resulting in increased pressure in the tissues, intramedullary edema, decrease perfusion pressure, and ischemic injury.[1]

Muscles

Cord compression can cause both upper motor neuron and lower motor neuron disease. Compression involving descending motor pathways and motor nerve roots can affect lower motor neurons that could result in flaccid paralysis of the muscles innervated if there is no prompt identification and correction of the underlying cause.

Physiologic Variants

Numerous variations exist throughout the spinal venous system.

- Variations of intramedullary veins:

Venous angiomas, also called developmental venous anomalies are normal variants of intramedullary spinal veins and appear to correlate with cavernous malformations.[1]

- Variations of the anterior spinal vein:

There is considerable variability in the course that the anterior spinal vein takes in becoming the vein of the filum terminale. It has been shown to deviate from the conus medullaris and course along a sacral or lumbar nerve root.

- Variations of the posterior spinal veins:

The position, course, and anastomotic pattern of the posterior spinal veins show considerable variability. It is usually a single vessel near the conus, but it can be paired or form a plexus called the posterior venous plexus.[3] Truncular type drainage exists in 80% of cases and plexiform type drainage 20% of cases.

- Variation of radicular veins:

While 60% of radicular veins exit the dura with the nerve root, 40% exit through different foramina between adjacent spinal nerves.[1]

Surgical Considerations

The great anterior radiculomedullary vein (GARV) due to its large size (diameter up to 2 mm) and location in the thoracolumbar region, may be confused with the artery of Adamkiewicz. However, the key to the differentiation of these two vessels is that the artery of Adamkiewicz often has a very sharp ‘hairpin’ configuration at its junction with the longitudinal spinal veins of the extrinsic venous system, while the GARV forms a less acute angle described as a ‘coat hook’ configuration.[1][2]

Clinical Significance

Spinal venous pathology can be due to vascular, neoplastic, or infectious etiologies.

The presence of a spinal epidural abscess usually results in congestion within the internal vertebral venous plexus. This enlarged venous plexus can mechanically compress the spinal cord resulting in myelopathy. Sepsis can also occur by way of the vertebral plexus. Also, since direct connections exist between the pelvis, the Batson plexus, and cranial venous sinuses, emboli and malignancies can disseminate via this hematogenous route.[1]

The most common pathologies involving the spinal venous system are arteriovenous fistula (AVF) and arteriovenous malformation (AVM), of which there are four types. Myelopathy can result from several mechanisms depending on the location and classification of the lesion. Possible mechanisms include hemorrhage into the cord parenchyma or mass effect from hemorrhage, vascular steal, venous hypertension, and congestion. The typical result of all these mechanisms is venous outflow obstruction and compressive myelopathy. Other vascular lesions include aneurysms and neoplastic vascular lesions such as hemangioblastomas and cavernous malformations.[5]

Type 1 Arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) are called dural AVFs and occur when a surface spinal cord vein directly receives blood from a nearby radicular artery. This vascular lesion consists of a single vessel, is located on the dura [5] and most commonly occurs where radicular veins exit the dura, given that its integrity becomes compromised in that area. Type 1 AVFs have a predilection for the thoracolumbar region.[1] Blood flow is usually slow and can flow either forward into the vertebral venous plexus or backflow into the spinal veins of the extrinsic system. With the feeding artery directly draining into the radicular vein, the vein becomes arterialized with increased venous pressure, hyalinized thickened walls, and also becomes more tortuous.[5] This pressure often backs up into the perimedullary venous plexus on the surface of the cord, and ultimately within the intramedullary radial veins.[6] Venous hypertension results over time, which causes decrease perfusion of the cord parenchyma, cord edema, decreased arterial perfusion, ischemia, and hypoxia; this manifests as progressive myelopathy.[7] MRI is diagnostic and usually shows hyperintensity with peripheral sparing (cord edema), serpentine, and dilated intervertebral veins, along with flow voids within engorged perimedullary venous plexus. Flow voids are seen with T2 weighted images and refer to the loss of MRI signal in flowing fluids such as blood, CSF, and urine. It is related to the velocity of moving protons within the flowing fluid.[6] This backward flow causes damage to the spinal cord parenchyma. A complete angiographic workup is needed because 15 to 20% of people with Type 1 AVFs have other AVMs.[5]

Type 2 Intramedullary AVMs are usually found in younger patients and most commonly in the thoracolumbar (70%) and cervical cord (30%). Lesions are located intradurally within the spinal cord parenchyma and usually consist of a medullary artery draining into a nidus. Flow is high, which may cause arterial steal from adjacent spinal cord segments. Patients often present with hemorrhage into the spinal cord, resulting in damage via mass effect, vascular steal, or venous hypertension. The rate of hemorrhage is similar to cerebral AVMs - 4% annually and 10% if a prior bleed has occurred. They are considered the true AVMs of the spine and are similar to cerebral AVMs.[5]

Type 3 AVMs are called juvenile AVMs. They involved both intradural and extradural areas simultaneously, such as the spinal cord parenchyma, the vertebrae, and paraspinal muscles. This malformation is large, and the nidus usually receives blood from several arteries that enlarges the vein. Hemorrhage presents in 33% of cases, and 50% of patients have associated aneurysms. The annual hemorrhage rate is 2.1%. Patients may present with symptoms of venous congestion, mass effect, and arterial steal syndrome. These AVMs are called Cobb syndrome when the complete somite is involved.[5] There is an association of this malformation with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.

Type 4 AVMs are called intradural-perimedullary AVFs. These are direct shunts between the pial venous plexus and arteries on the surface of the spinal cord, which results in a dilated aneurysmal venous pouch.[1] They are intradural but extramedullary. The pathophysiology of myelopathy resulting from this lesion is due to an increase in spinal venous pressure.

Other Issues

In addition to ensuring the preservation of spinal cord blood flow following surgery for AVFs obliteration, it is essential to accurately identify all the arterialized veins that drain the fistula and to achieve complete interruption of the fistula as recurrence can cause progressive myelopathy.[8] Traditional methods to confirm fistula obliteration are invasive intraoperative intravascular pressure measurements and intraoperative angiography, followed by postoperative angiograms at follow-up. The use of Doppler technology intraoperatively has several benefits. It allows for fistula identification before entering the dura, which allows for a more restricted hemilaminectomy. Doppler is also a noninvasive way of confirming the obliteration of the fistula and even may eliminate the need for follow-up postoperative angiograms.[8]

Multiple sclerosis patients have demonstrated chronic internal jugular, vertebral, and azygos vein obstruction, which causes congestion in the spinal venous system. It is still uncertain if this chronic cerebral venous insufficiency plays any role in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis.