Introduction

The spinal cord is a collection of nerve tissue extending from the caudal aspect of the brainstem to the lumbar region of the spinal canal. It terminates at approximately the level of the L2 vertebral body as the conus medullaris. Together with the brain, it comprises the central nervous system (CNS). The spinal cord has various functions, which include: conveying afferent, sensory information from the peripheral nervous system to the brain; transmitting signals from the motor cortex of the brain to the periphery; and serving as the center of reflex responses.

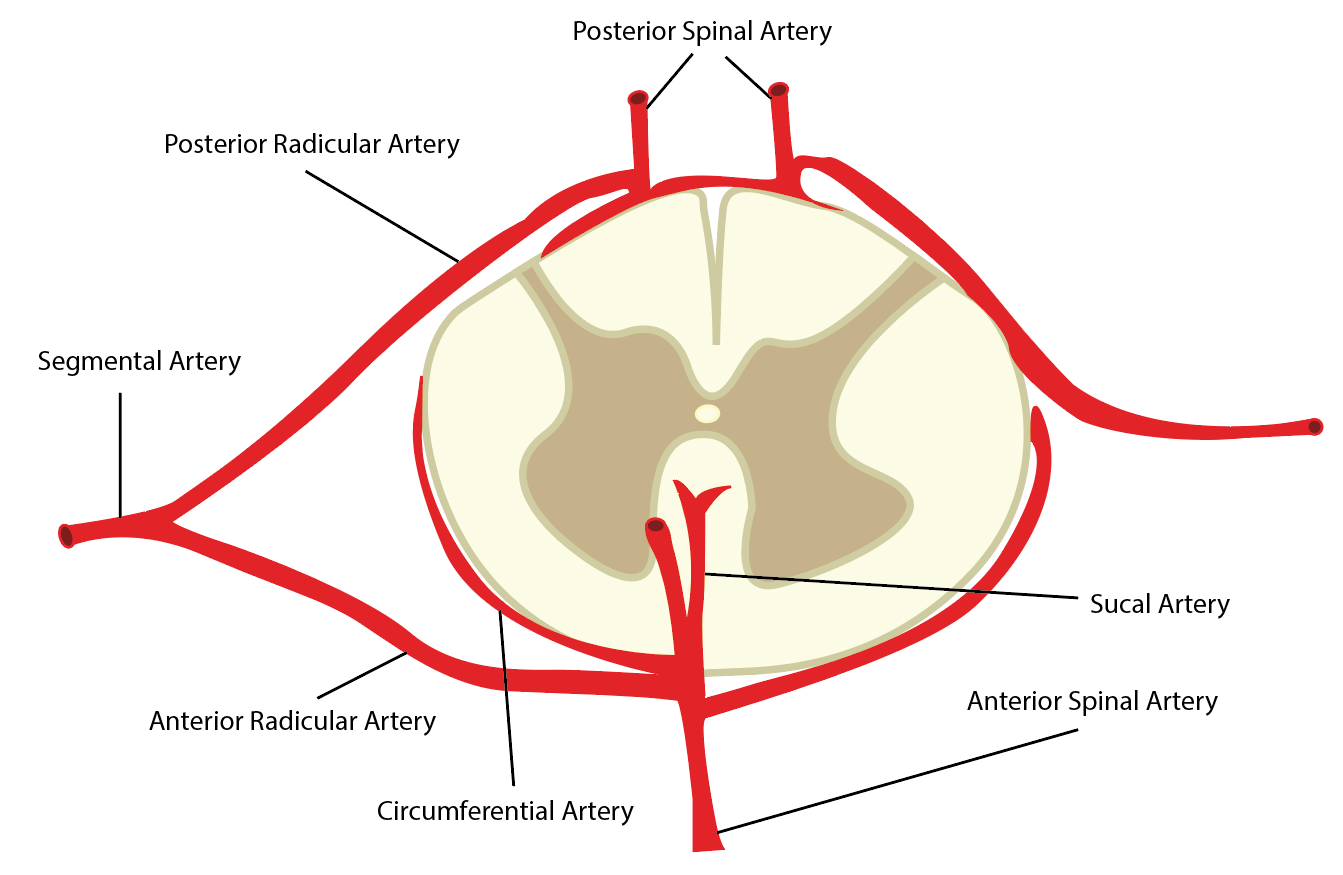

Arterial supply to the spinal cord is vital to supplement the high metabolic requirements of this nervous tissue. The vasculature has a certain degree of variability, although common features and structures exist. It includes vasculature lying directly superficial to the cord that courses longitudinally along the structure and radicular arteries that supply the cord transversely in a segmental fashion.

Structure and Function

Blood supply to the spinal cord is highly complex and anastomotic to ensure adequate supply to the entire structure. Variability in the vasculature is not uncommon. Additionally, blood flows preferentially to certain regions of the spinal cord, particularly the cervical and lumbar enlargements.[1]

Longitudinally, the spinal cord receives vascular supply by the anterior spinal artery (ASA) and a pair of posterior spinal arteries (PSA). These three arteries typically originate from the distal vertebral arteries at the superior aspect of the spinal cord. However, some literature has described the PSAs as branches of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. The ASA is the predominant supply of the spinal cord. It supplies the anterior two-thirds of the cross-sectional area through its terminal branches, the central arteries. The paired PSAs provide blood to the spinal posterior one-third cross-sectional area. The three vessels also connect circumferentially around the structure via the pial plexus, often referred to as the vasocorona. It supplies the periphery of the cord via small perforators, known as rami perforantes.[2][3]

Segmentally, numerous anterior and posterior radicular arteries (see below) provide collateral blood flow to the entire vertebral column, including the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs, in addition to the spinal cord.[1][3]

Embryology

The cardiovascular system is the initial organ system formed in neonatal development. Its primary functions include gas exchange, nutritional supplementation, and metabolic waste removal to maintain the viability and growth of the cells and tissues. Additionally, the vascular system is a significant provider of hormonal regulation and guidance, specifically the vascular endothelial growth factor (VGEF).[4][5]

During development, the peri-neural vascular plexus (PNVP) supplies blood to the spinal cord. Some of the PNVP eventually integrates into the CNS to become the intra-neural vascular plexus (INVP). The INVP is susceptible to environmental and hormonal cues that lead to preferential patterning of blood supply.[5]

Present throughout the CNS vascular system, the blood-brain barrier (BBB) plays an important role in protecting the neural tissue from variations in blood composition in addition to blood-borne pathogens. The BBB derives from the development of widespread tight junctions formed by endothelial cells that prevent cellular diffusion into the neural tissues.[6]

The artery of Adamkiewicz is a vital vessel that supplies the lumbar spinal cord. It is often identified by a trademark “hairpin” loop that arises due to differential growth of the spinal column and the spinal cord.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Cervical Spinal Cord

Arterial supply to the cervical spinal cord displays a marked variation between individuals because of differences in embryonic development—the ASA and two PSAs branch off the distal vertebral arteries at the level of the foramen magnum. The ASA courses midline on the ventral sulcus of the spinal cord, while the PSAs travel parallel to each other in a paramedian location on the dorsal aspect. In the cervical spine, two or three supportive anterior and posterior radiculomedullary arteries branch from the vertebral arteries. The largest of these radiculomedullary vessels is the artery of cervical enlargement, usually identified between the C4-C8 vertebral levels, most often coursing along the C6 nerve root. The radiculomedullary arteries join with the ASA and PSAs to carry supplemental blood flow to these nervous tissues. The provision of supplemental flow to the cord is from branches of the vertebral, ascending cervical, and deep cervical arteries, and potentially the ascending pharyngeal and occipital arteries.[1][3]

Thoracic Spinal Cord

The diameter of the ASA through the thoracic spinal cord is notably narrower compared to its size in the cervical and lumbar regions. Thus, much of the blood flow to the thoracic spine derives from segmental arteries branching from the dorsal aorta. Most often, nine pairs of posterior intercostal arteries in addition to one pair of subcostal arteries supply the spinal cord in the thorax; however, variation in the quantity of segmental vasculature is not uncommon. Rostral to the T3 level, the segmental arteries arise from the supreme intercostal artery, also known as the superior intercostal artery. Caudal to this level, minor segmental arteries branch directly from the dorsal aorta and derive their name according to the rib under which they track. Anatomically, the minor segmental arteries branch from the aorta at one to two vertebral levels caudal to their perfusion site and are seen traveling in an upward course from their site of origin to the spinal column.[3]

Lumbar Spinal Cord

The largest and most important radiculomedullary artery supplying the lumbar spinal cord is the artery of Adamkiewicz (AKA). Like most other vasculature structures supplying the spinal cord, its level of origin is variable based on embryonic development. It usually originates between T8-L2, most commonly at T10/T11. The artery lies to the left of the spinal cord and forms a hairpin loop as it bifurcates into ascending and larger descending branches to meet the ASA. There is little, if any, collateral blood supply inferior to the AKA and ASA junction on the cord’s anterior surface. However, the largest posterior radiculomedullary artery often enters the spinal cord below the junction of the AKA and ASA, serving as the most distal collateral blood supply to the cord.[1][3]

The ASA and the two PSAs course caudally past the conus medullaris. At this level, the ASA is at its thickest. After coursing inferiorly past the conus, with the filum terminale, the ASA ends as a collection of rami cruciantes that anastomose with each distal PSA.[3]

Physiologic Variants

The vasculature of the spinal cord is highly variable in size and structure. This is attributable to differences in embryological development and proliferation as well as metabolic needs. Some variants are described in the text above, such as the development of the artery of Adamkiewicz, the branching origin of the PSAs, and the number of segmental radicular arteries supplying the thoracic spinal cord. However, these are not the only identified instances of variation in spinal cord vasculature.

Rather than existing as a single continuous vessel, duplication of the ASA until the C5/C6 level is common. Radicular arteries supplying the ASA also differ in both number and origin. Literature has identified the average number of cervical radicular arteries to be two to three, arising from all branches of the subclavian artery in the neck. Specifics are less defined in the thoracic and lumbar regions due to an even more irregular and unpredictable pattern display.

The PSAs display an equal amount of irregularity. The posterior spinal arteries are more numerous and richer in collateralization than their anterior counterpart. They often present as discontinuous in a cruciate configuration and provide blood supply to the spinal cord in a contralateral fashion.[1][2][3]

Surgical Considerations

Many vascular complications can arise during surgical procedures of the spine. Besides the complex vasculature providing blood flow to the nervous structures in the spinal cord, the vertebral column is near vital vascular structures, including the aorta, iliac vessels, and carotid and vertebral arteries. Anterior cervical exposures come close to the carotid sheath, and injuries to the carotid artery—especially during revision surgery—have been documented.[7] Posterior cervical procedures, mainly those involving lateral mass screw placement, risk injuring the vertebral arteries that course in the transverse foramina, entering the C6 and exiting the C2 vertebrae.[8]

Potential vascular complications in the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine are injuries to the major vessels and their branches and the sequelae of compromising the blood supply to the thoracic and/or lumbar spinal cord. Paraplegia due to a unilateral vascular injury of a thoracic segmental vessel is uncommon. However, bilateral disruption of the segmental blood supply, such as in the case of aortic surgery or aortic dissection, presents a higher risk of paraplegia.[9] Thoracic and vascular literature has extensively documented the consequences of bilateral disruption of the blood flow to the thoracic cord during complex thoracic and thoracolumbar aneurysm reconstructive surgery.[10]

The transthoracic approach to the anterior thoracic spine typically requires the mobilization of segmental arteries over several vertebral levels. A right-sided approach is recommended to avoid the pericardial structures since the artery of Adamkiewicz has been reported to originate on the left side of the aorta between T8 and L1 in 75% of patients.[11]

Clinical Significance

Adequate vascular supply to the spinal cord is vital in maintaining the integrated function of the central nervous system. Supply to the cord is highly complex and interconnected to maintain the tissue’s metabolic needs.

Acute central cord syndrome is the most common type of spinal cord injury, accounting for over two-thirds of all incomplete cervical spinal cord injuries. Its predominant etiology is from cervical spine hyperextension trauma that compresses the spinal cord. Trauma to the cord often results in centro-medullary hemorrhage and edema. Characteristic symptoms are upper extremity weakness, sensory deficits, and bowel, and bladder dysfunction. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is vital for diagnosing central cord syndrome and other complications such as hemorrhage and spinal column instability. Treatment specifics vary based on severity, but ensuring spinal column stability is always paramount. Surgical approaches are necessary in severe cases with marked instability and neurological impairment.[12]

Spinal cord infarction (SCI) results from an interruption in spinal cord blood supply and can lead to acute spinal syndrome. Though the development of SCI is rare (comprises only 1% of stroke), infarct of the anterior spinal artery and/or the artery of Adamkiewicz is overwhelmingly more common than infarct of a posterior spinal artery. Lesions of the anterior supply lead to clinical presentation characterized as an anterior spinal syndrome. Symptoms will depend on the location and severity of the infarct but include sudden back pain progressing to sensation deficits, extremity weakness or paresis, and bladder or bowel dysfunction. Onset is typically sudden, with peak symptoms arising within 30 to 45 minutes. In the typical ASA infarct, the anterior two-thirds of the cord are affected, leading to bilateral weakness, progressive sensory loss, and potential autonomic symptoms. An infarct of a PSA will typically cause unilateral symptoms. Diagnosis is made via detection on MRI, often after visualization of the trademark “owl’s eye” hyperintensity appearance on T2 axial images. Underlying etiology is wide-ranging; thus, a range of treatment methods exist.[13][14]

Similarly, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) of spinal origin is uncommon but has received coverage in the literature. Spinal SAH is attributable to either arteriovenous fistula or malformation, as well as a spinal aneurysm. Symptoms usually include sudden onset neck or back pain and extremity weakness with signs indicating spinal cord compression. Again, computed tomogram (CT)/computed tomogram angiogram (CTA) and MRI are important for urgent diagnosis. Treatment varies depending on severity, location, and size, but both conservative treatment and endovascular or surgical management have proven effective.[15][16]