Introduction

The large intestine is the portion of the digestive tract where water is absorbed from indigestible material (see Image. Large Intestine). This section of the gut includes the cecum, appendix, entire colon, rectum, and anal canal. The large intestine begins at the terminal ileum with the cecum. Unlike the small intestine, the large bowel is shorter but has a much larger lumen. This segment is further distinguished from the small intestine by the presence of omental appendices, haustra, and teniae coli.[1][2][3] The omental appendices are small pouches of peritoneum filled with fat. The haustra are small pouches or sacculations that give the large intestine its segmented appearance. The teniae coli are 3 longitudinal bands of smooth muscle on the outer wall of the colon.

Disorders such as colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, and diverticulosis can impact large bowel function. Surgical interventions, such as colectomy, hemicolectomy, and proctectomy, are performed for colorectal cancer, severe inflammatory bowel disease, or bowel obstruction. A thorough understanding of the anatomy and function of this part of the digestive tract will help clinicians diagnose and manage gastrointestinal disorders, optimize surgical interventions, and improve patient outcomes.

Structure and Function

The key functions of the large intestine include the following:

- Absorption of water, nutrients, and vitamins

- Fecal compaction

- Potassium and chloride secretion

- Propulsion of waste toward the rectum

The cecum, the proximal blind pouch of the ascending colon, is located at the ileocecal junction in the right iliac fossa. The terminal ileum opens into the cecum through the medial wall. The ileocecal valve regulates this passage. Although the cecum lacks a mesentery, it remains highly mobile within the right iliac fossa. The appendix, a thin cylindrical structure measuring approximately 6 to 10 cm, is attached to the cecum at its posteromedial wall, about 1 to 2 cm below the ileocecal junction. The tip of the appendix often extends into the peritoneal cavity, most commonly resting in a retrocecal position. A short, triangular mesentery, the mesoappendix, provides vascular supply to the appendix.

The cecum is continuous with the 2nd part of the large intestine, the ascending (right) colon. This part of the large bowel runs superiorly along the right side of the abdomen, extending from the right iliac fossa to the right lobe of the liver. At this point, the right colon makes a left turn at the right colic (hepatic) flexure to continue as the transverse colon. The ascending colon is a retroperitoneal organ, with the right paracolic gutter—a deep vertical groove—separating its lateral side from the adjacent abdominal wall.

The transverse colon, the 3rd part of the large intestine, is the longest and most mobile segment. This central portion extends between the right and left colic flexures. The left colic (splenic) flexure is less mobile than the right and is anchored to the diaphragm by the phrenicocolic ligament. The transverse colon is suspended by a mesentery, the transverse mesocolon, which has its root along the inferior border of the pancreas. At the splenic flexure, the transverse colon transitions into the descending (left) colon.

The descending colon, a retroperitoneal structure, is positioned adjacent to the paracolic gutters. This segment terminates at the sigmoid colon, the 5th part of the large intestine. The sigmoid colon, an S-shaped loop of variable length, connects the left colon to the rectum and becomes the rectum at the level of S3.

The rectum occupies the concavity of the sacrococcygeal curvature. This segment of the large intestine is a fixed structure, primarily retroperitoneal and subperitoneal in location. At the level of the puborectal sling, formed by fibers of the levator ani muscles, the rectum transitions into the anal canal. The middle segment of the rectum, known as the ampulla, serves as an expanded reservoir for fecal storage.

The rectum has distinct anterior relationships depending on sex. In the male body, the rectum is positioned anterior to the rectovesical pouch, prostate, bladder, urethra, and seminal vesicles. In the female body, this section of the gut lies anterior to the rectouterine pouch, cervix, uterus, and vagina.

Embryology

Embryologically, the colon develops from 3 regions: the midgut, which gives rise to the cecum, appendix, ascending colon, and proximal 2/3 of the transverse colon; the hindgut, which forms the distal 1/3 of the transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, and upper anal canal; and the proctodeum, which contributes to structures below the dentate line. The midgut derivatives receive blood supply from the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), while the hindgut derivatives are supplied by the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA).

By week 5 of development, the primary intestinal (midgut) loop forms, with its apex connected to the yolk sac via the vitelline duct. The cephalic limb of this loop develops into the distal duodenum, jejunum, and part of the ileum, while the caudal limb gives rise to the distal ileum, cecum, appendix, ascending colon, and proximal 2/3 of the transverse colon.

During week 6, the midgut loop undergoes a 90° counterclockwise rotation as it herniates through the primitive umbilical ring, a process known as physiological umbilical herniation. At week 10, the herniated intestinal loop returns to the abdominal cavity, completing an additional 180° counterclockwise rotation, reducing the physiological umbilical herniation. In total, the midgut loop rotates 270° counterclockwise around the SMA axis.

The hindgut develops into the distal 1/3 of the transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, and upper anal canal. The hindgut also forms the epithelial lining of the bladder and urethra. The urorectal septum partitions the lower hindgut (cloaca) into the urogenital sinus anteriorly and the rectum with the upper anal canal posteriorly, extending to the pectinate line.

Below the pectinate line, the lower anal canal arises from an invagination of the surface ectoderm, called the proctodeum. The junction between the upper and lower anal canal is marked by the cloacal (anal) membrane, which degenerates to establish continuity between the 2 segments.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

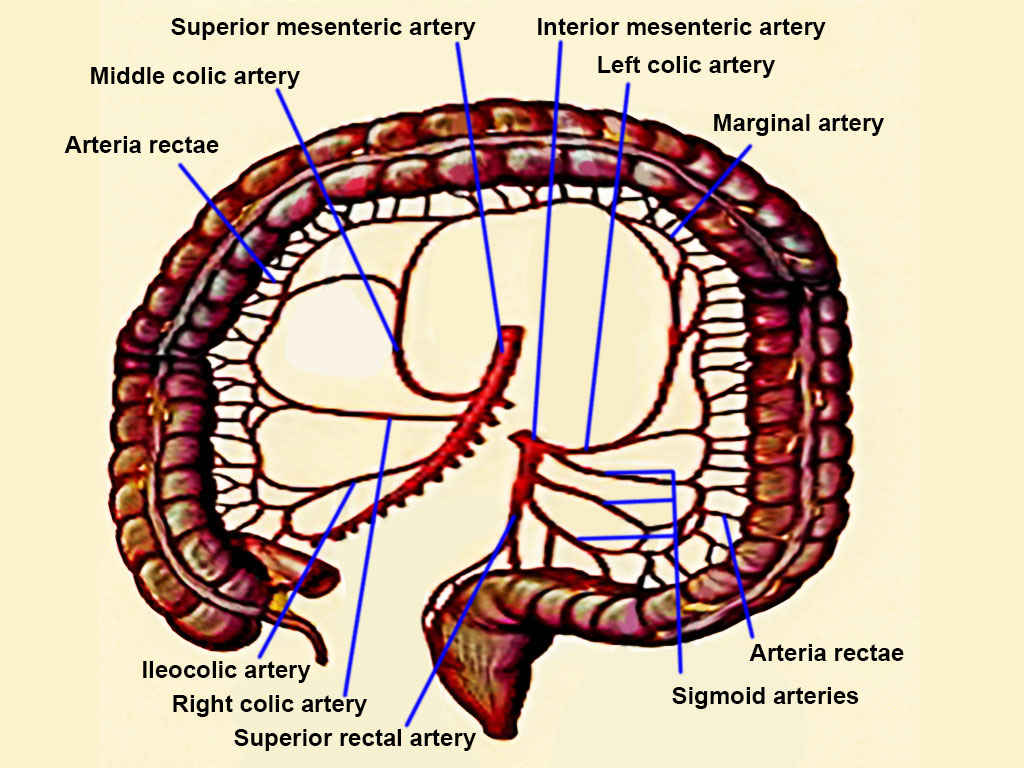

The SMA and IMA supply blood to the large intestine. These 2 vessels communicate through the marginal artery, which runs parallel to the entire length of the colon (see Image. Arteries of the Large Intestine).

The cecum receives blood from the ileocolic artery, a terminal branch of the SMA. This artery also gives rise to the appendicular artery, which supplies the appendix. The ascending colon and right colic flexure derive their blood supply from the ileocolic and right colic arteries, both branches of the SMA.

The transverse colon primarily receives arterial supply from the middle colic artery, another branch of the SMA. Additional blood flow comes from anastomotic arcades between the middle and left colic arteries, which contribute to the formation of the marginal artery (of Drummond).

The descending and sigmoid colonic segments are perfused by the left colic and sigmoid arteries, branches of the IMA. The transition of blood supply at the left colic flexure, where the SMA gives way to the IMA, marks the embryological shift from the midgut to the hindgut.

The rectum and anal canal receive blood from multiple sources. The superior rectal artery, a continuation of the IMA, supplies the upper portion. Additional contributions come from the middle rectal artery, a branch of the internal iliac artery, and the inferior rectal artery, which arises from the internal pudendal artery.[4][5]

Venous drainage generally follows the arterial supply. The inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) drains into the splenic vein, while the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) joins the splenic vein to form the hepatic portal vein. Lymphatic drainage of the large intestine follows the pathways of the primary blood vessels, directing fluid to their associated lymph nodes.[6]

Nerves

The midgut-derived ascending colon and proximal 2/3 of the transverse colon receive parasympathetic, sympathetic, and sensory innervation from the superior mesenteric plexus. The hindgut-derived structures, including the transverse colon's distal 1/3 and the descending and sigmoid colon, are innervated by the inferior mesenteric plexus.

Surgical Considerations

The appendix and the transverse and sigmoid colonic segments are intraperitoneal structures. However, the cecum is also intraperitoneal, as it is covered by the peritoneum on all sides and lacks a mesentery. The right and left colon, the rectum, and the anal canal are retroperitoneal structures.

Several surgical techniques are available for colonic resection, including right hemicolectomy, extended right hemicolectomy, left hemicolectomy, extended left hemicolectomy, and abdominoperineal resection. Simple excision with primary anastomosis is another option. Side-to-side and side-to-end anastomoses are preferred over transanal anastomoses due to a lower risk of anastomotic leakage.[7] The choice of procedure depends on the site and severity of colonic disease. When an anastomosis is not feasible, an ostomy allows stool to exit the body into an ostomy bag.[8][9][10]

Colonic ischemia (ischemic colitis) is a serious complication following aortic surgery or any perioperative event that leads to hypotension. This condition typically manifests as abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea in the postoperative period. Preventing ischemic colitis requires careful fluid management during the perioperative phase.[11][12]

Clinical Significance

The marginal artery of Drummond is a prominent collateral vessel that supplies the splenic flexure and plays a critical role in maintaining blood flow when a major colonic artery becomes occluded. Various conditions can affect the colon, including diverticular disease, colorectal cancer, bowel obstruction, lower gastrointestinal bleeding from polyps and arteriovenous malformations, strictures, and abnormal peristalsis. Colonic perforation is an uncommon cause of retroperitoneal abscess, occurring when the perforation involves the ascending or descending colon.[13]