Introduction

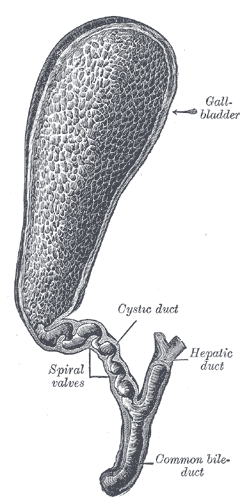

The gallbladder is a pear-shaped organ in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen (see Image. The Gallbladder and Bile Ducts Laid Open). It measures approximately 7 cm to 10 cm in length and 4 cm in width. Even though the organ is small, it is a common cause of abdominal pain due to gallstones, which often require surgical removal of the organ. Anatomically, the gallbladder is located anteriorly on the undersurface of liver segments IV and V. There are many variants of the anatomy of the biliary system, making exact knowledge of these anatomic possibilities crucial when performing gallbladder and biliary surgery. The gallbladder has an inferior peritoneal surface and a superior liver surface. It has no capsule; however, some authors describe an extension of the liver capsule (Glisson's capsule) covering the exposed surface of the gallbladder body. The gallbladder fundus is wide, and as it continues into the main body, it narrows in diameter. The gallbladder body tapers into the infundibulum, which connects to the neck and cystic duct. At the distal portion of the gallbladder and into the cystic duct are Heister spiral valves. These valves may be responsible for aiding gallbladder emptying with neural and hormonal stimulation. In most people, there is an inferior outpouching of the gallbladder infundibulum or neck called Hartmann's Pouch. Occasionally, a paucity is located at the top of the gallbladder fundus. This is called a Phrygian cap and has no pathologic or surgical significance.[1]

Embryology

By the end of the fourth week of embryogenesis, the hepatic diverticulum outpouches from the developing duodenum. The hepatic diverticulum becomes the biliary tree, while a second outpouching, known as the cystic diverticulum, immediately below develops into the gallbladder. The development of the biliary tree is extremely diverse among humans and leads to numerous variations of the biliary system.[2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

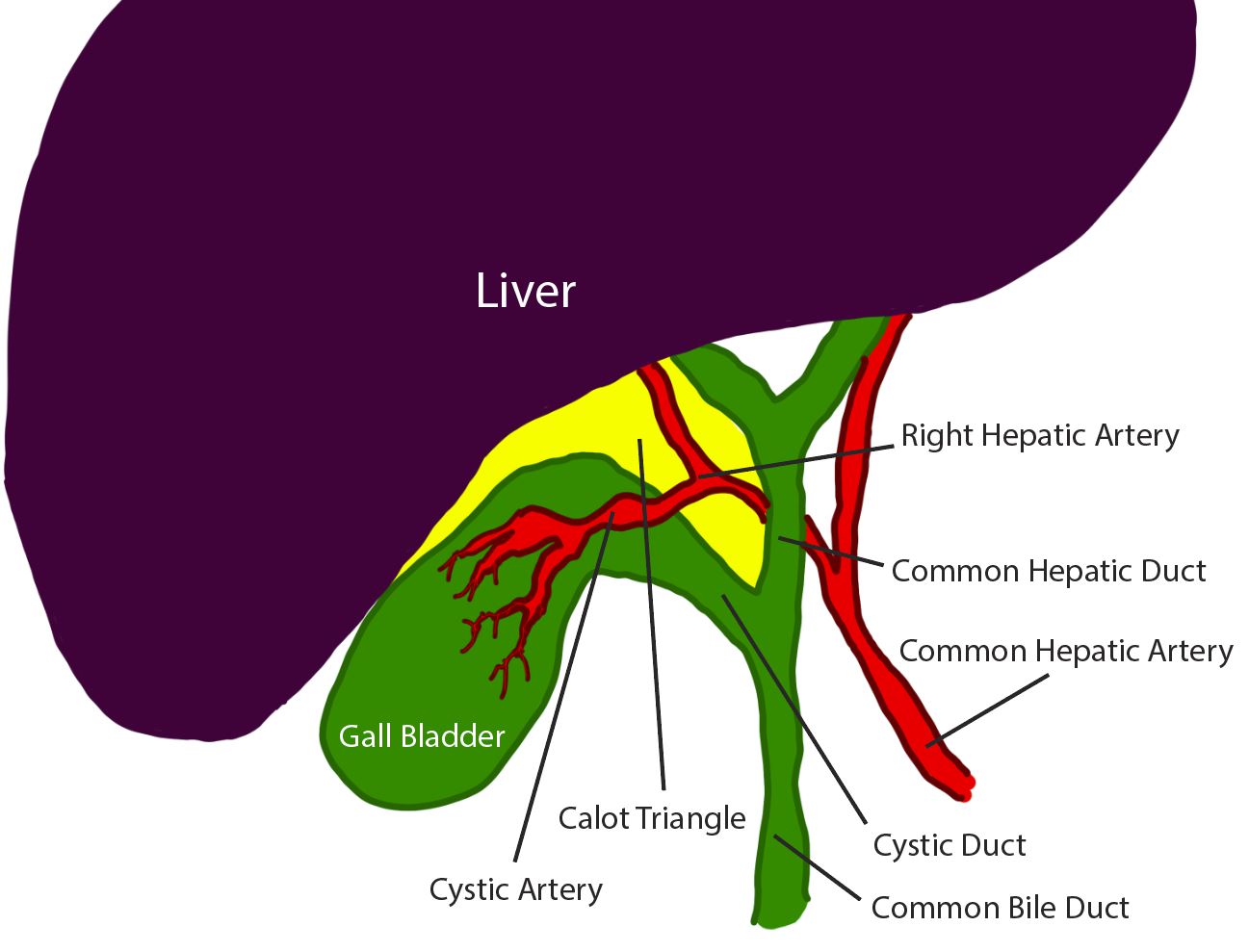

The gallbladder receives most of its blood supply from the cystic artery. The cystic artery is a branch of the right hepatic artery that arises from the common hepatic artery. Anatomic variants of this vascular supply are also frequently encountered. The common bile duct receives blood from the proper hepatic, the right gastric, the gastroduodenal, and the posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries. These small vessels must be preserved during surgery to ensure adequate cystic and common bile duct perfusion. Disruption of these vessels increases rates of duct ischemia and leaks. There is no formal cystic vein. Venous drainage directly empties into the gallbladder bed of the liver by short venules from the gallbladder into the liver parenchyma. Larger venous sinuses of the liver can also be encountered during cholecystectomy, and these can be problematic when trying to control bleeding. Subserosal and submucosal lymphatics drain the gallbladder to the cystic lymph node of Lund or node of Calot located in the Calot triangle (see Diagram. Diagram of the Calot Triangle and Local Anatomy). Cancer of the gallbladder often bypasses this lymph node and spreads directly to nodes located in the porta hepatis.[3]

Nerves

The gallbladder and cystic duct receive innervation from the following 3 nerves: 1) the right phrenic nerve conveys sensory information, 2) the hepatic branch of the right vagus nerve provides parasympathetic innervation, and 3) the celiac plexus provides sympathetic information. Gastric surgeries such as resections, bariatric procedures, or vagotomies done for peptic ulcer disease de-innervate the gallbladder and cause dysfunction of the organ. This, in turn, leads to the formation of gallstones and cholecystitis. When such surgeries are often performed, prophylactic cholecystectomies are done simultaneously to prevent cholecystitis.[4]

Surgical Considerations

The triangle of Calot is of surgical importance. It has the following boundaries: 1) cystic duct on the right, 2) common hepatic duct on the left, and 3) the undersurface of the liver superiorly. The original definition of this triangle from 1891 listed the cystic duct, common hepatic duct, and the cystic artery as boundaries. This has since been modified to allow for better identification of landmarks for locating the cystic artery. Of surgical importance is that within the modern definition of the triangle of Calot, it runs the cystic artery and lymph node. Sometimes, the gallbladder neck is connected to the first part of the duodenum with loose fibrous bands known as the peritoneal cholecystoduodenal fold.

The left and right hepatic ducts join outside the liver to form the common hepatic duct. The cystic duct joins the common hepatic duct after exiting the gallbladder to form the common bile duct. The short common bile duct travels inferiorly in the hepatoduodenal ligament along with the hepatic artery on the right and the portal vein posteriorly. The normal common bile duct diameter varies from 4 mm to 7 mm. Dilation of this duct usually indicates a distal obstruction from a common bile duct stone, benign stricture or neoplasm of the bile duct, pancreatic head, or ampulla Vater.

The union of the pancreatic duct forms the distal end of the common bile duct to form the common channel known as the ampulla of Vater. The ampulla of Vater is surrounded by a smooth muscle called the sphincter of Oddi, which prevents the reflux of duodenal secretions into the bile duct.

Microanatomy

The gallbladder wall is composed of several layers. The innermost layer comprises columnar epithelium arranged in a microvillous formation, like the intestine's lining. The other layers are the lamina propria, smooth muscularis, and serosa. Rotitansky-Aschoff sinuses are deep inclusions from the mucosal layer extending into the muscularis layer.[5]

Clinical Significance

The gallbladder stores bile (30 ml to 50 ml), which is released during the digestive and absorptive processes in the intestine. Contraction of the gallbladder with the release of bile into the biliary tree and duodenum is caused by gastric distension and fatty food content. This stimulates the secretion of cholecystokinin (CCK) from inclusion cells of the duodenum, which causes gallbladder contraction. Disruption of neuro innervation, blockage of the cystic duct from gallstones, or other etiologies can cause chronic or acute cholecystitis symptoms. Tests such as a nuclear HIDA (hepatobiliary) scan with CCK or ultrasound are used to diagnose gallbladder disease. The gallbladder is distensible; when the cystic duct is obstructed, it can enlarge to twice its size. This may result in infection requiring surgical removal.[6]