Introduction

The anterolateral abdominal wall includes the front and side walls of the abdomen.

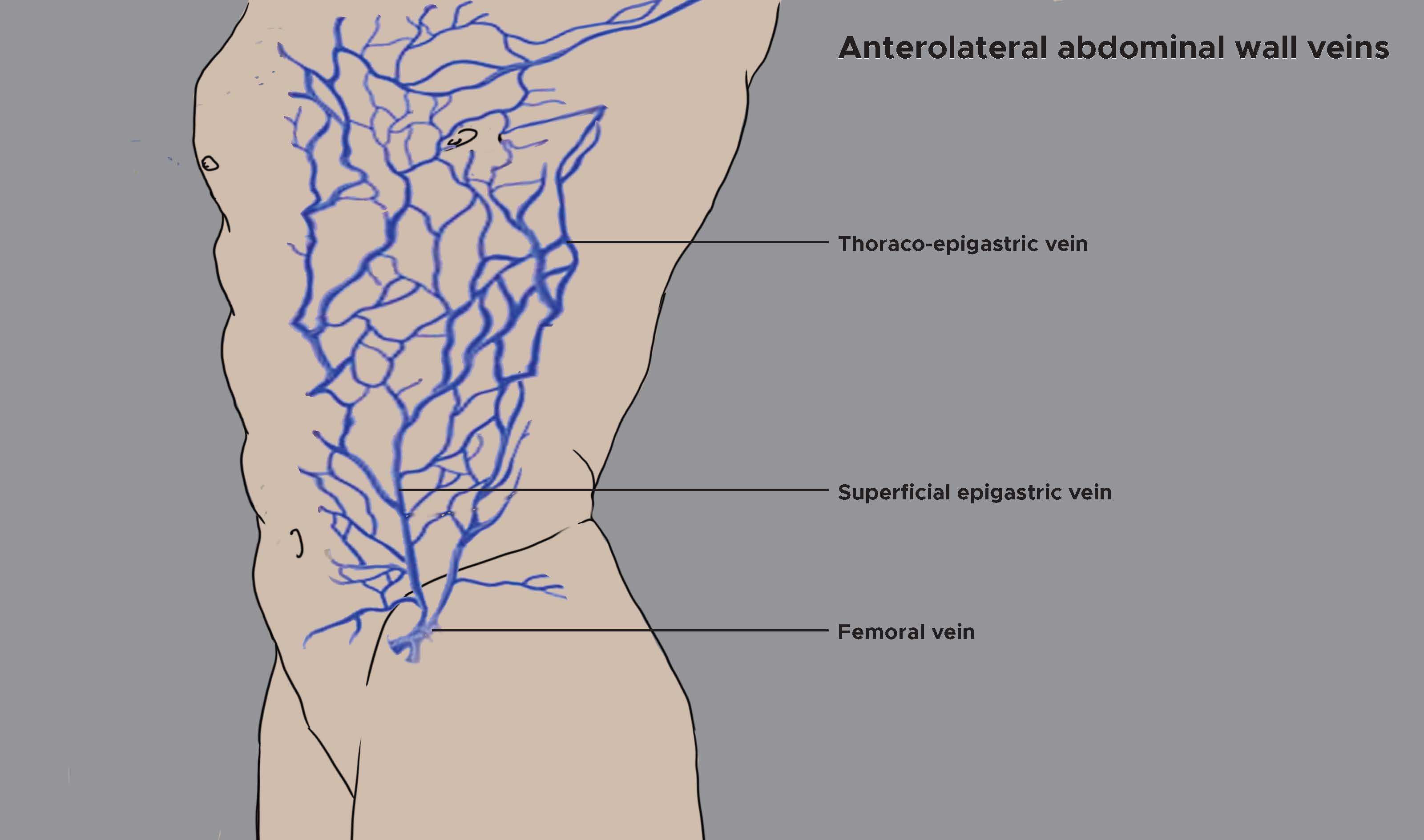

The venous drainage of the superficial anterolateral abdominal wall involves an elaborate subcutaneous venous plexus. This plexus drains superiorly and medially to the internal thoracic vein. It drains superiorly and laterally to the lateral thoracic vein. Further, the plexus drains inferiorly to the superficial epigastric vein and the inferior epigastric vein which are tributaries of the femoral vein and external iliac vein, respectively.

A layer of connective tissue lining the abdominal cavity namely the extraperitoneal fascia lies deep to the transversalis fascia and contains varying amounts of fat. The vasculature extending into mesenteries is located in this extraperitoneal fascia which is abundant on the posterior abdominal wall, especially around the kidneys, and continues over organs covered by peritoneal reflections.

Structure and Function

The veins of the anterolateral wall carry deoxygenated blood into the systemic venous circulation and back to the lungs for oxygenation. The superficial abdominal veins dilate and provide a collateral circulation when the portal vein, superior vena cava, or the inferior vena cava get obstructed. The obstruction causes dilated, distended, and tortuous veins often resembling the venomous serpents on the head of the Greek god “Medusa” giving rise to the term “Caput Medusae.”[1][2][3]

Embryology

Veins of the systemic circulation are derived from the cardinal veins, and a portion of the inferior vena cava (IVC) along with the portal venous system are derived from the vitelline veins of the abdominal wall, which drain into systemic veins.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The veins of the anterolateral abdominal wall accompany the arteries supplying the anterior abdominal wall.[4][5][6]

Veins

Superficial Venous Drainage

The venous drainage of the anterior abdominal skin around the midline is by branches of the superior and inferior epigastric veins. The skin of the flanks is drained by branches of the intercostal, lumbar, and deep circumflex iliac veins. Also, the skin in the inguinal region is drained by the superficial epigastric, the superficial circumflex iliac, and the superficial external pudendal veins, tributaries of the femoral vein.

- The anterior cutaneous veins carrying deoxygenated blood from the superficial abdominal wall are tributaries of the superior and inferior epigastric veins and accompany the anterior cutaneous nerves.

- The lateral cutaneous veins are tributaries of the lower intercostal veins and accompany the lateral cutaneous nerves.

- The superficial inguinal veins drain into the femoral vein and drain the skin of the lower part of the abdomen. The superficial epigastric vein runs upward and medially and drains the skin up to the umbilicus. The superficial external pudendal veins run medially then pass in front of the spermatic cord and drain the skin of the external genitalia and the adjoining part of the lower abdominal wall. Laterally, the superficial circumflex iliac vein runs just below the inguinal ligament and receives blood from the skin of the abdomen and thigh.

Deep Venous Drainage

The anterior abdominal wall is drained by:

- Two large veins from above: the superior epigastric (medial) and musculophrenic (lateral)

- Two large veins from below: the inferior epigastric and the deep circumflex iliac

- Small tributaries of the intercostal, subcostal and lumbar veins, which accompany the corresponding arteries

The superior epigastric vein and musculophrenic vein are the two terminal tributaries of the internal thoracic vein inferior epigastric vein. The anterior intercostal veins carry deoxygenated blood from the diaphragm, the anterior abdominal wall and the seventh, eighth, and ninth intercostal spaces and continue upward and laterally along the deep surface of the diaphragm as far as the tenth intercostal space of the abdominal wall

The inferior epigastric vein drains into the external iliac vein near its lower end just above the inguinal ligament. It runs upward and medially in the extraperitoneal connective tissue, passes just medial to the deep inguinal ring, pierces the fascia transversalis at the lateral border of the rectus abdominis and enters the rectus sheath by passing in front of the arcuate line. Within the sheath, it drains the rectus muscle and ends by joining with the superior epigastric vein.

The venous drainage from the lateral abdominal wall drains above mainly into the axillary vein via the lateral thoracic vein and below into the femoral vein via the superficial epigastric and the superficial circumflex iliac vein. The level of the umbilicus is a watershed. Venous blood and lymphatic fluid drain upward above the plane of the umbilicus and downward below this plane.

Surgical Considerations

Veins of the anterolateral wall can get dilated due to multiple causes. Obstruction of the superior vena cava or inferior vena cava (by a mass or thrombus) can present as dilated, tortuous veins over the abdomen. Urgent surgery may be required in such situations. Supra-umbilical median incisions through the linea alba have several advantages such as being bloodless as most vasculature courses lateral to the linea alba. Furthermore, these incisions are safe to muscles and nerves but tend to leave a postoperative weakness through which a ventral hernia may form.[7]

Clinical Significance

Among the sites at which tributaries of the portal vein anastomose with systemic veins (portocaval anastomoses), the umbilicus is one of the important sites. Cutaneous veins surrounding the umbilicus (tributaries of the superficial and inferior epigastric veins) anastomose with small tributaries of the portal vein called paraumbilical veins. Elevated pressures of the portal venous system cause these anastomoses to recanalize to create dilated veins radiating from the umbilicus called caput medusae and can also result in esophageal and rectal varices. However, the blood flow in the dilated veins is normal and does not break the barrier of the watershed line.

The blockage of the hepatic portal vein or vascular channels in the liver can interfere with the pattern of venous return from abdominal parts of the gastrointestinal system. Vessels that interconnect the portal and caval systems can become greatly distended and tortuous, allowing blood in tributaries of the portal system to bypass the liver, enter the systemic caval system, and thereby return to the heart.

In vena caval obstruction, the thoracoepigastric veins open up, connecting the great saphenous vein with the axillary vein. In a superior vena cava obstruction, the blood in the thoracoepigastric vein flows downward, breaking the barrier of water-shed line. In an inferior vena cava obstruction, the blood flows upward, once again crossing the watershed line.