Introduction

The abdominal wall surrounds the anterolateral aspect of the abdominal cavity, where many important organs are located.[1][2][3]

Chief layers of the abdominal wall include:

- Skin,

- Superficial fascia (the subcutaneous tissue which forms the thin, single layer above the umbilicus. Below the umbilicus, it is divided into two layers (1) the fatty superficial layer called Camper’s fascia and (2) the deep layer called Scarpa's fascia. Blood vessels and nerves run between these two layers.)

- Muscle,

- Fascia,

- Parietal peritoneum.

Structure and Function

The major functions of the abdominal wall include:

- Providing a durable and flexible covering to prevent the abdominal viscera from leaving the abdominal cavity.

- Protecting internal abdominal organs from trauma/injury.

- Maintaining the anatomical position of the abdominal organs.

- Assisting expiration by pushing the abdominal organs towards the diaphragm.

- Assisting in coughing and vomiting by increasing intra-abdominal pressure.

Embryology

At around the second week of life, the embryo starts to grow and fold upon itself. During this time, there are specific events controlled by growth factors that are occurring that include cellular differentiation, multiplication, migration, and deposition of cells at different sites. Several of these events coincide with the formation of the abdominal wall, and it is at this point that certain abdominal wall defects occur.

The embryo comprised of the ectoderm is a flat structure within the umbilical ring; it will become the surface epithelium and the endoderm, which will become the inner epithelium of the organs in the digestive tract.

As the embryo changes shape, the mesoblast layer starts to form and plays a vital role in the development of the basic abdominal wall structures. At about 3 to 4 weeks, the abdominal and thoracic cavities are distinct, and the folding of the embryo starts to develop along two perpendicular axes but in four directions: caudal, cranial, and laterally on each side. The cranial fold will contain the embryonic derivatives that eventually will come from the epigastric and thoracic walls. The caudal fold will lead to the development of the bladder, hindgut, and hypogastrium. The lateral folds will lead to the development of the lateral abdominal walls and midgut.

The ectoderm will remain in continuity with the amnion and ultimately will form the umbilical ring around a yolk sac which is quickly dissolving. The umbilical ring contains the umbilical vessels, allantois, vitelline duct, extraembryonic coelom, and associated vitelline vessels.

The next stage is the development of the abdominal wall at 6 to 10 weeks. As the midgut grows rapidly, it is at this stage that congenital defects of the abdominal wall appear.

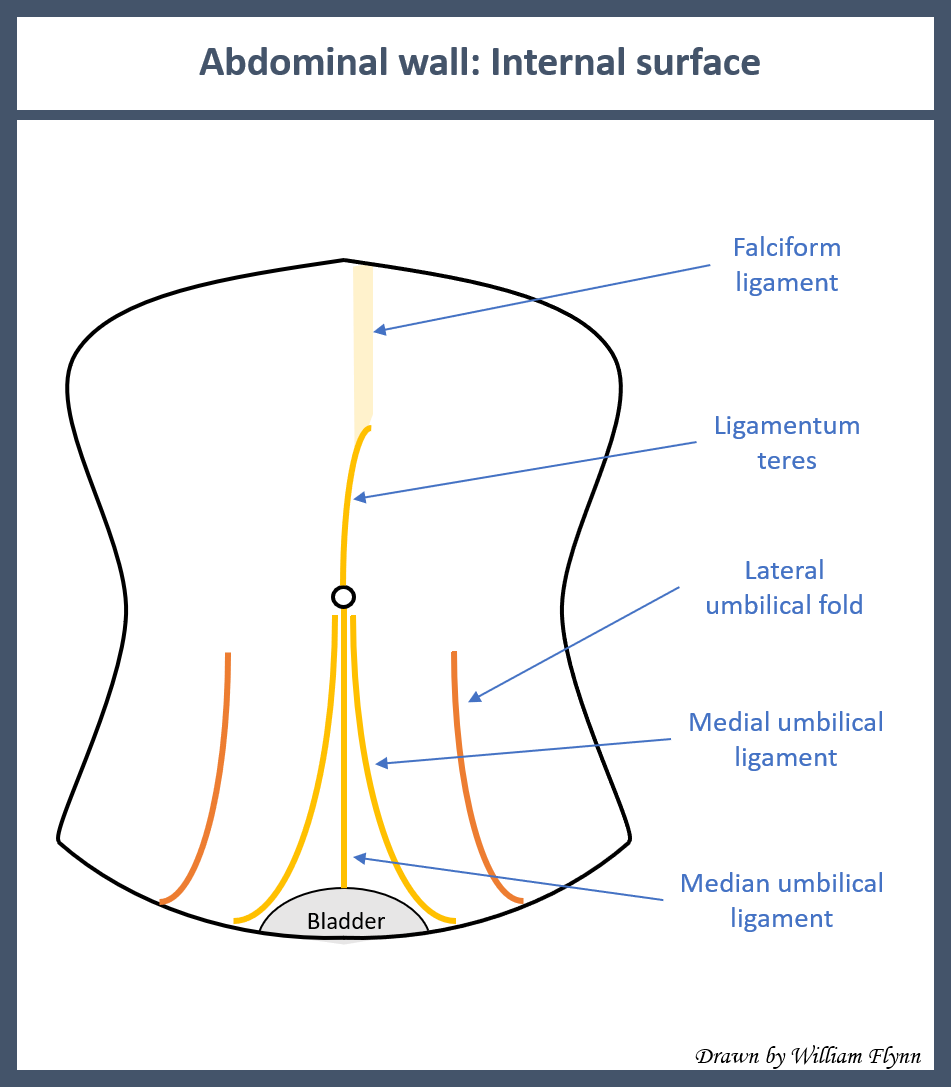

In the presence of normal development, there is a rotation of the midgut which returns to the abdominal cavity around weeks 10 to 12. If the abdominal wall development is not proper, the intestinal contents will remain herniated inside the umbilical cord. By the twelfth week, there is the obliteration of the extraembryonic space and the intestine returns to the abdominal cavity. At the same time, the vitelline duct, allantois, and other vessels are obliterated, leaving just two umbilical arteries and one umbilical vein covered by amnion.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The anterior abdominal wall is supplied by the following:

- Superior epigastric artery

- Inferior epigastric artery

- Deep circumflex iliac

- Superficial epigastric vessels

- Superficial circumflex iliac

There are thoracoepigastric veins running longitudinally which connect the lateral and superficial epigastric veins.

Nerves

Nerves of the anterior abdominal wall include:

- Subcostal nerve

- Iliohypogastric

- Ilioinguinal

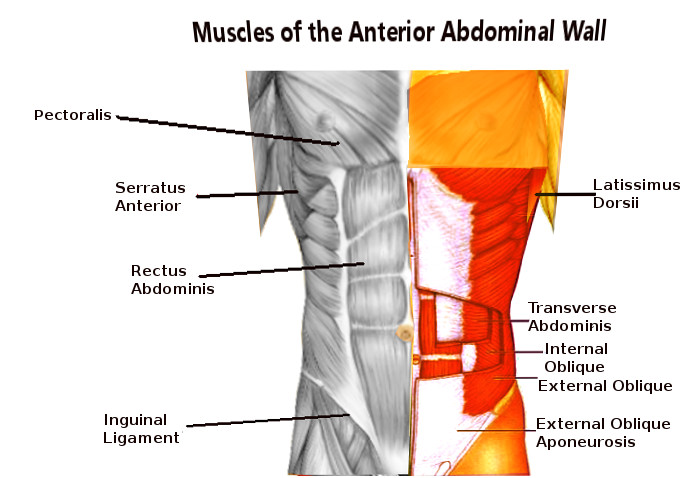

Muscles

The five muscles in the abdominal wall are divided into two groups: (1) two vertical muscles situated near the midline of the body and (2) three flat muscles located laterally and stacked on top of each other. The three flat muscles include the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis. The flat muscles flex and rotate the trunk. Because the fibers of these muscles criss-cross and interlink with each other, they also strengthen the abdominal wall and reduce the risk of herniation.[4][5][6]

Flat Muscles

- External Oblique - the most superficial and also the largest flat muscle of the abdominal wall. It runs in an inferior-medial direction and at the midline, its fibers form an aponeurosis and in the midline merge with the linea alba. This fibrous structure extends from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis.

- Internal Oblique - located deeper to the external oblique and is much thinner and smaller. Its fibers run superomedial and near the midline form an aponeurosis which contributes to the linea alba.

- Transversus Abdominis - the deepest of the flat muscles and its fibers run transversely. It also continues to the linea alba in the midline. Just beneath the transversus abdominis muscle is the transversalis fascia.

Vertical Muscles

- Rectus Abdominis - long paired vertical muscle located on either side of the midline. It is divided into two segments by the linea alba. The lateral border of the muscle is called the linea semilunaris. At several locations, the muscle is intersected by fibrous intersections which give rise to the “six-pack” seen in athletes. The rectus abdominis compresses the abdominal viscera, prevents herniation, and stabilizes the pelvis during ambulation.

- Pyramidalis - vertical muscle shaped like a triangle. It is located superficial to the rectus abdominis and located at the base of the pubic bone. The apex of the triangle attaches to the linea alba.

Rectus Sheath

The Rectus Sheath is an aponeurosis formed by the five muscles of the abdomen. It has an anterior and posterior wall for most of its length. The anterior wall is formed by the aponeuroses of the external oblique and half of the internal oblique. The posterior wall is formed by the aponeuroses of half of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis. About midway between the umbilicus and pubic symphysis, there is only the anterior wall of the rectus sheath and no posterior sheath. At this junction, the rectus abdominis muscle is in direct contact with the transversalis fascia. The area of transition at which the posterior wall disappears is the arcuate line.

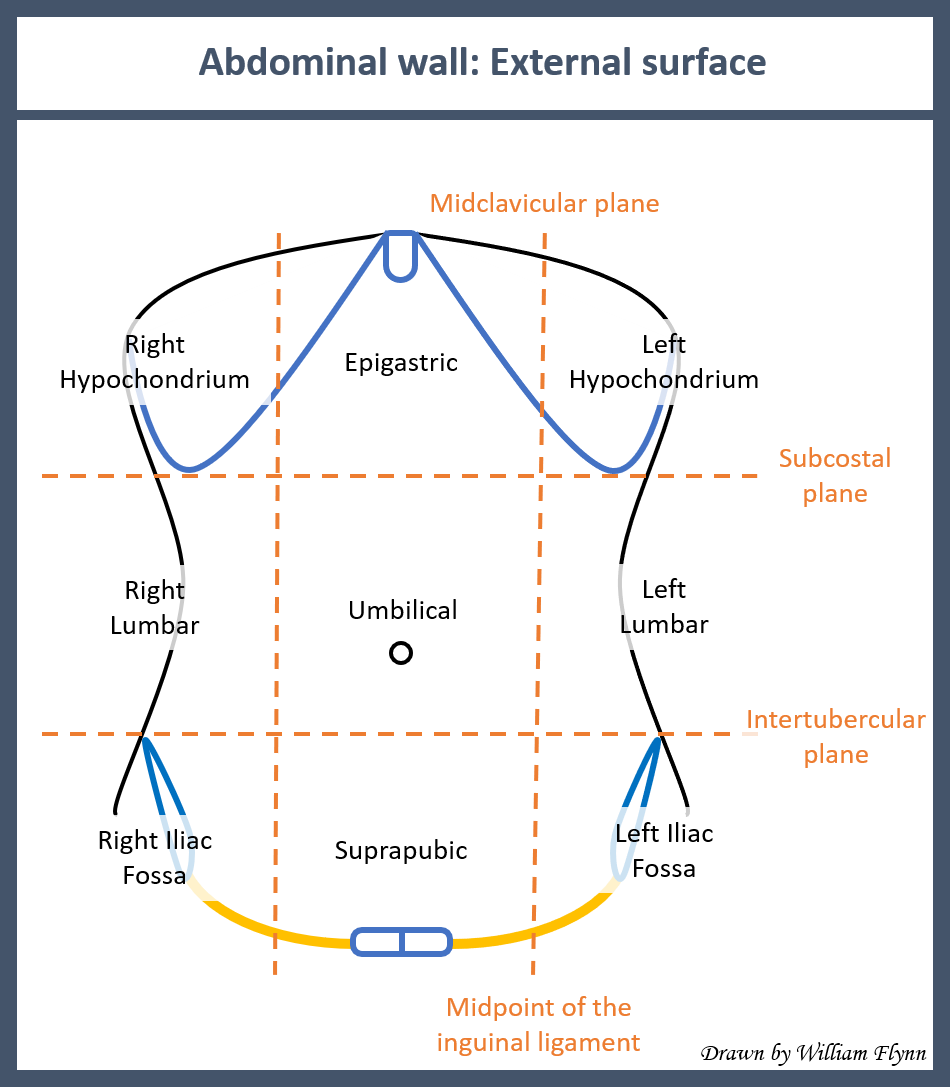

Surgical Considerations

Surgeons need to understand the anatomy of the abdominal wall so that the correct incision is made when entering the abdominal cavity.[7][8]

- A midline incision is made through the linea alba with a slight curve at the umbilicus. The linea alba is poorly vascularized, and hence blood loss is minimal, and no nerves are excised. This is perhaps the most versatile incision when approaching abdominal organs.

- A paramedian is an incision made just lateral to the linea alba. It provides access to the kidney, adrenal, and spleen. However, this incision is rarely used today as it required ligation of blood vessels and cutting of nerves.

- A transverse incision is made below the umbilicus. It was once used, but since it has poor healing, this incision is rarely used today.

- Pfannenstiel or suprapubic transverse incision is made just a few centimeters above the pubis. Before making this incision, the bladder must be emptied/decompressed to prevent injury.

- A subcostal incision is made just below the rib cage and allows access to the spleen or gallbladder. It is a limited incision with restricted exposure.

- McBurney’s incision consists of splitting the muscle fibers instead of cutting them. It is located a third of the distance from the anterior superior iliac spine and the umbilicus. It is widely used during an appendectomy.

Clinical Significance

The major pathology of the anterior abdominal wall are hernias that include the following:

- Umbilical

- Femoral

- Inguinal

- Ventral

- Incisional

- Spigelian