Continuing Education Activity

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD) is a rare clinical entity, often forgotten in the typical differential, but when identified, the treatment of it has the potential to improve the quality of a patient's life. The typical patient, for this diagnosis of exclusion, will present with recurrent biliary colic-type symptoms, generally after completion of a cholecystectomy, often in concert with transaminitis, pancreatitis, or both. More severe cases can progress to clinically apparent obstructive jaundice and chronic pancreatitis, although rare. While several of these signs and symptoms are also present in more morbid disease processes, once those are ruled out, attention should then be turned to Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction as a possible cause for the patient's complaints. This activity describes the evaluation and management of Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and reviews the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of the sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, medical conditions, and emergencies.

Assess the appropriate evaluation of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction.

Evaluate the management options available for sphincter of Oddi dysfunction.

Describe interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the care of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and improve outcomes.

Introduction

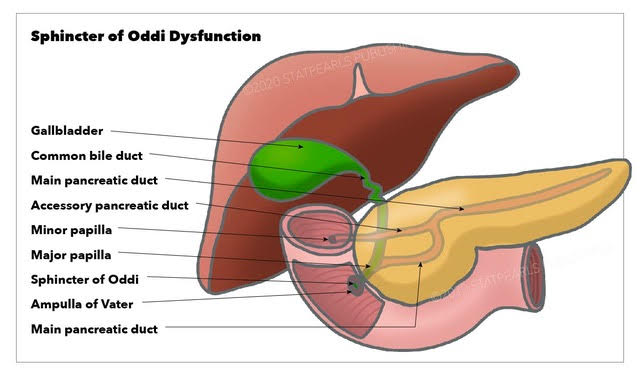

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD) is a rare clinical entity, often forgotten in the typical differential. When identified, its treatment has the potential to improve a patient's quality of life significantly. In a diagnosis of exclusion, the typical patient presents with recurrent biliary colic-type symptoms, generally after undergoing cholecystectomy, often in concert with transaminitis, pancreatitis, or both. More severe cases can progress to clinically apparent obstructive jaundice and chronic pancreatitis, although rare. While several of these signs/symptoms are also present in more morbid disease processes, once ruled out, attention should be turned to the SOD as a possible cause for the patient's complaints. See Image. Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction.

Etiology

The exact etiology of SOD is unclear. Conceptualizing this disease process is easier when it is understood that SOD is a broad term describing a spectrum of hepatobiliary disorders. These clinical entities result from many types of sphincter dysfunction, including spasms, strictures, or inappropriate relaxation. Moreover, this disease process can involve either biliary or pancreatic sphincters.[1] Clinical sequelae are reflective of the comingled nature of these organ systems.

Epidemiology

SOD occurs most frequently in females, generally aged 20 to 50. The prevalence is approximately 1.5%, but this is likely an underestimate due to under-testing and a lack of concrete biochemical markers for identification.[1] In persons with recurrent idiopathic pancreatitis and chronic pancreatitis, the prevalence of SOD may be as high as 72% and 59%, respectively.[2] Therefore, SOD should be much higher in the astute provider's differential. Risk factors for the development of SOD multiple include prior cholecystectomy, gallbladder agenesis, cholelithiasis, previous gallstone lithotripsy, liver transplantation, alcohol use disorder, hypothyroidism, and irritable bowel syndrome.[1][3] While this list is quite varied, an insult to the pancreaticobiliary system that could impact sphincter function or flow of bile is conceivable in each setting.

Pathophysiology

The Sphincter of Oddi has 3 main functions: regulation of bile flow into the duodenum, prevention of reflux into the bile or pancreatic duct, and promotion of gallbladder filling in between digestive cycles (see Image. Sphincter of Oddi, Anatomy). The basal pressure of the sphincter is 10 mmHg with an intermittent phasic increase in tone 2 to 6 times per minute of 50 to 140 mmHg. Cholecystokinin has been demonstrated to relax basal tone and inhibit phasic contractions. Cholecystokinin is released from enteroendocrine cells in response to a meal, exerting direct hormonal effects on the sphincter. Other gastrointestinal peptides have varying influences on the sphincter; these include gastrin, secretin, motilin, and octreotide.

Additionally, the sphincter is extrinsically controlled via parasympathetic innervation. This vagal innervation is mostly excitatory. As referenced above, SOD commonly presents with recurrent biliary colic-type abdominal complaints. Both stenosis and dyskinesia of the sphincter can result in the hallmark constellation of symptoms seen in this disease. It is theorized that trauma from stone passage can result in sphincter stenosis. While congenital syndromes and motility disorders may serve as the nidus for dyskinetic sphincter function, all of these can result in a pathologic process that falls under the umbrella of SOD.

History and Physical

Most patients presenting with SOD complain of biliary-type pain. Their discomfort is mostly located in the epigastrium and right upper quadrant, with radiation to the back and shoulder. It usually lasts around 30 minutes to several hours before resolving spontaneously.[1] This pain can be accompanied by nausea and vomiting. In contrast to biliary colic, symptoms are generally not post-prandial in nature, unless the primary source of their sphincter dysfunction relates to the pancreatic ductal component of the sphincter. Recurrent or chronic pancreatitis may also signify underlying sphincter dysfunction.

Evaluation

Given the overlap of SOD symptoms with other biliary pathology, most patients undergo abdominal imaging (US, CT, HIDA scan, etc). However, in the algorithm for SOD, these studies are generally low-yield. But they can be beneficial in ruling out other more sinister pathology before focusing on SOD as the cause of the patient's complaints. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with manometry is considered the gold standard test for SOD.[4] Basal sphincter pressures of more than 35 to 40 mmHg on manometry are consistent with the diagnosis of SOD.[1] Importantly, however, even this modality may overlook patients with clinically apparent SOD. For types I, II, and III, the frequency of abnormal sphincter of Oddi manometry was (shown to be) 85.7%, 55.1%, and 28.1%, respectively.[5] Thus, for even the most clinically sound patient presentations (type I), some 15% of people failed to demonstrate the expected manometry, suggesting that isolated sphincter pressure measurements may not fully assess a disease process with more intermittent symptoms. Thus, although ERCP with manometry is the gold standard, it is only a single component of the diagnostic workup, which should be considered alongside other measures.

Laboratory evaluation should also be performed, specifically, a comprehensive metabolic panel, amylase, and lipase, to evaluate for hepato-pancreatic dysfunction. Functional examinations like the Nardi test can also help confirm the diagnosis. The Nardi test involves the simultaneous administration of morphine and neostigmine. The former causes biliary contraction, and the latter contracts the Sphincter of Oddi. The forward pulsion of bile into a contracted sphincter should reproduce the patient's symptoms if SOD is the source of their symptoms.[1] The patient's presentation, in combination with the results of their examination, should be used to stratify them into 3 classes of SOD. Specific diagnostic criteria for SOD include:

- Transaminitis (greater than 2 times the upper limit of normal on 2 or more occasions

- Common bile duct dilation (greater than 10 mm on US; greater than 12 mm on ERCP)

- Biliary pain

Utilizing these criteria, patients are classified as follows:

- Type I SOD: all 3

- Type II SOD: biliary pain and 1 of the other 2 criteria.

- Type II SOD: biliary pain only[3]

The results of this classification impact the subsequent treatment plan.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of SOD is aimed at reducing the basal pressure and resistance of the valve.[1] Noninvasive options include calcium channel blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, glyceryl trinitrate, and somatostatin, each with varying levels of success. For example, in a randomized controlled trial, nifedipine decreased cumulative pain scores and the number of symptom episodes, emergency department visits, and pain medication consumption compared to placebo.[6] However, combinations of the aforementioned therapies show even greater levels of symptom reduction. One study utilizing a combination of nifedipine, tricyclic antidepressants, and glyceryl trinitrate showed that 15.3% and 59.3% of patients reported complete symptom resolution or improvement in symptoms, respectively.[7]

Invasive interventions for the treatment of SOD include ERCP with sphincterotomy. This modality is highly effective and generally safe for patients with SOD, with reports of 90% and 70% resolution of symptoms in types I and II SOD, respectively.[1] Intrasphincteric botulinum toxin injections have been shown to reduce sphincter tone by approximately 50%, but unfortunately, they did not resolve patient symptoms in a small case series.[8] However, both botulinum toxin and stent placement have been suggested as possible interim steps to clarify whether or not sphincter relaxation/stenting resolves symptoms, thereby providing a means to predict patient response to a more definitive sphincterotomy. Patients with type I and type II SOD should be referred for management with ERCP and sphincterotomy. Type III SOD has been shown in a trial not to respond to procedural intervention.[9] These patients should instead be referred for medical management, including pain control, as discussed above.

Differential Diagnosis

As stated previously, SOD is generally regarded as a diagnosis of exclusion. The differential for epigastric or right upper quadrant pain is wide. It is, therefore, important that appropriate testing is performed to rule out other disease processes prior to formally diagnosing and treating SOD. The spectrum of obstructive biliary pathologies, including choledocholithiasis and malignant conditions such as cholangiocarcinoma, should receive specific attention. These must be considered if bile duct dilation and elevated transaminases are present.

Prognosis

While this disease process is not inherently dangerous, effective treatment may improve the patient's quality of life. While all-comers with suspected SOD may undergo ERCP and possible sphincterotomy, this is not necessarily warranted. Those with the greatest symptom improvement are types I and II, particularly with abnormal sphincter manometry. However, even in these patients, symptoms generally do not resolve entirely, suggesting a multifactorial cause for pain.[10] Predictions regarding responsiveness to intervention can be derived from the Milwaukee classification of SOD. Here, patient presentation, laboratory data, and imaging findings stratify patients to SOD types 1, 2, and 3, with clinically predictable responses to sphincterotomy available in this framework.[1]

Complications

Complications to the management of SOD are generally related to those seen with ERCP and other endoscopy evaluations. Perforation, anesthetic morbidities, and post-ERCP pancreatitis are inherent risks.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

SOD is a rare clinical entity, often neglected in the differential diagnosis. To that end, this disease process's workup, diagnosis, and management requires an interprofessional approach. Surgeons and gastroenterologists are most likely to encounter these patients and should maintain a healthy index of suspicion for this diagnosis of exclusion. Primary care physicians and pain management specialists should also know this clinical entity. Endoscopic proceduralists have a primary role in performing ERCP, manometry, and sphincterotomy. Nurses, technicians, and anesthesia providers assist them at each step. Finally, the medical management of this disease is facilitated by pharmacists and their staff.