Introduction

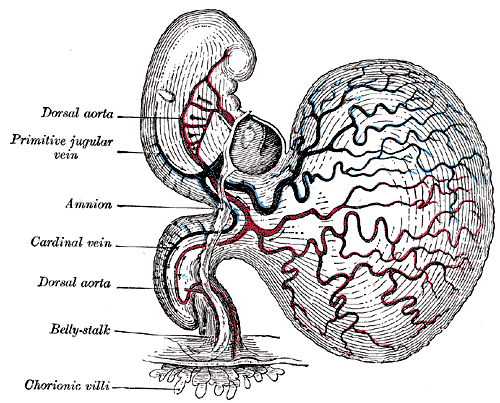

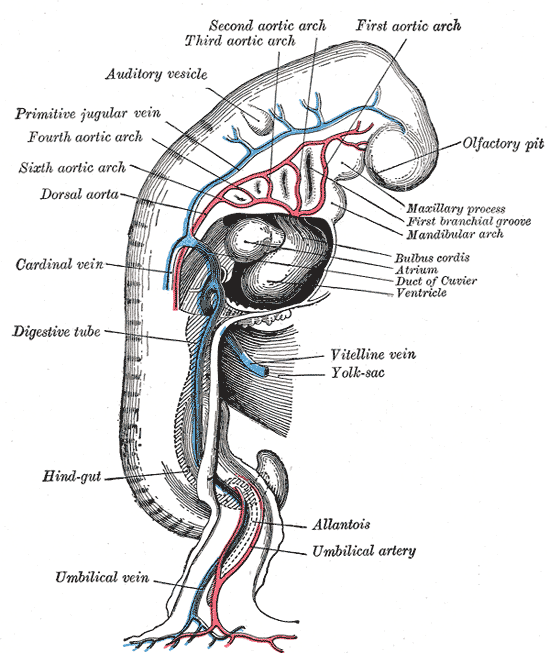

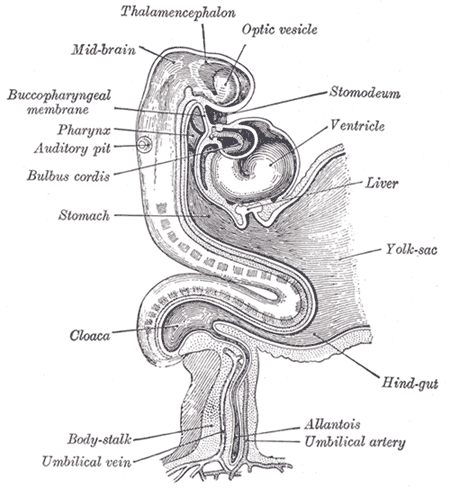

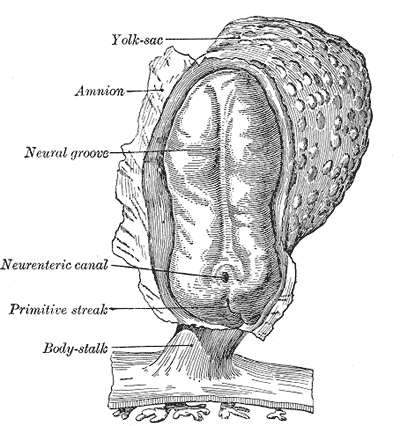

The yolk sac, or umbilical vesicle, is a small membranous structure outside the embryo with various functions during embryonic development (see Image. Human Embryo at 14 Days With Yolk Sac). The yolk sac reduces in size, communicates ventrally with the developing embryo via the yolk stalk, and later regresses. The yolk stalk is a term that may be used interchangeably with the vitelline duct, omphaloenteric duct, or omphalomesenteric duct. The yolk stalk serves to connect the yolk sac to the midgut, which is an early derivative of the gastrointestinal system (see Image. The Digestive Apparatus). Both the midgut and yolk sac are endodermal in origin. See Image. Embryology.

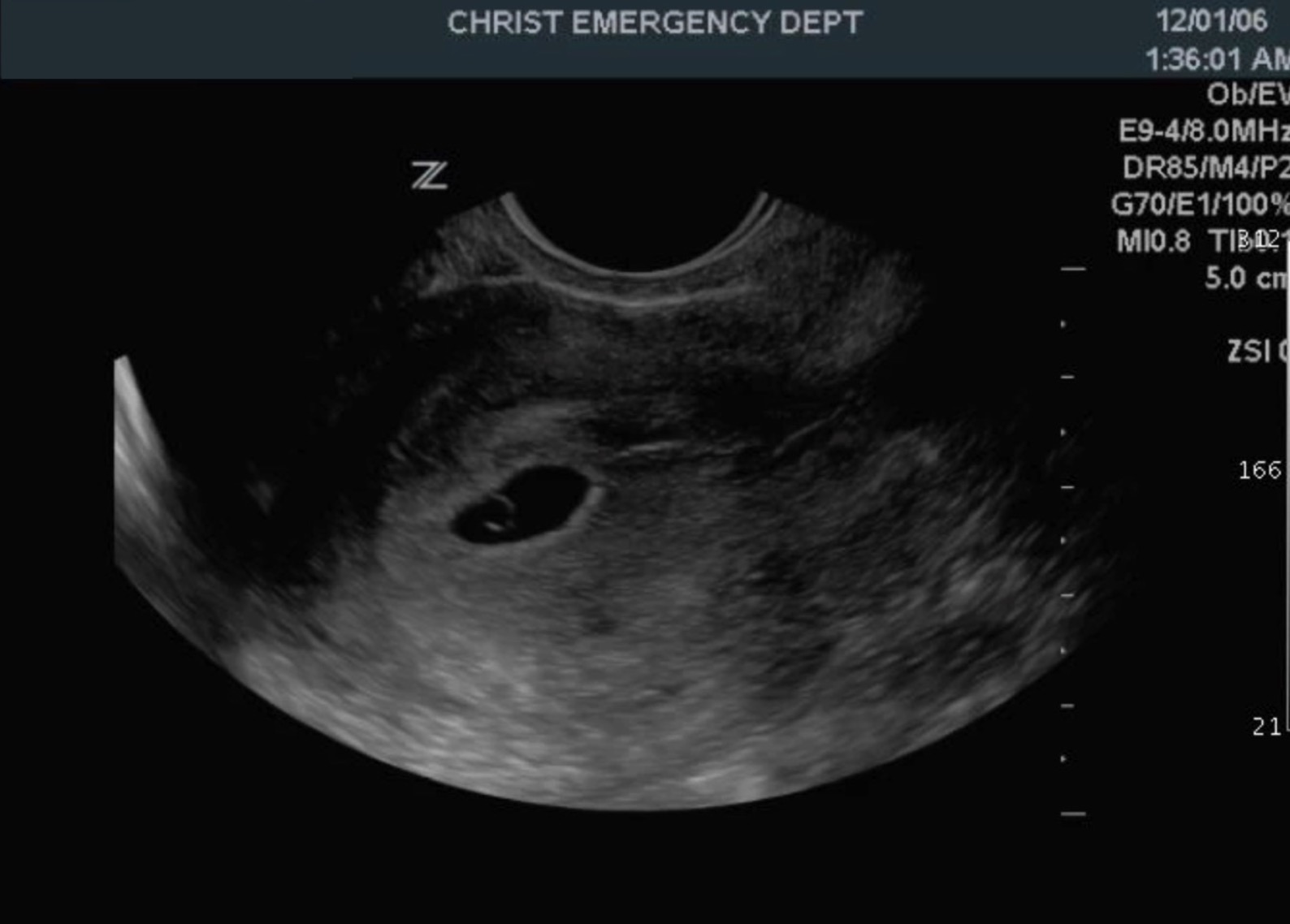

Although it contains no yolk in humans, the yolk sac has several critical biological functions during early gestation, including primitive hematopoiesis and germ cell production. Clinically, the yolk sac can be visualized using transvaginal sonography by five weeks post-fertilization, and its visual examination serves as a significant predictor of adverse pregnancy outcomes until its disappearance on sonography by the second trimester.

Development

The primary yolk sac, or primary umbilical vesicle, forms from proliferating hypoblast cells after implantation. The inner cell mass becomes a bilaminar embryonic disc as it divides into the hypoblast, which forms the yolk sac, and the epiblast, which forms the amnion. The yolk sac and amnion develop simultaneously, which begins during days 8 through 14 of embryogenesis. The yolk sac has a lining of extra-embryonic mesoderm. Part of yolk sac development involves the enlargement of the primary yolk sac, the sequestering and subsequent disappearance of a part of it, while the yolk sac that continues to develop is referred to as the secondary yolk sac. Although yolk sac formation starts during the second week of development, it cannot be visualized clinically on ultrasound until around five weeks post-fertilization (7 gestational weeks). Growth of the yolk sac progresses linearly during weeks 5 through 10 post-fertilization.

Gastrulation also occurs during the second week of development. This process involves the migration and invagination of blastocyst cells, ultimately transforming the bilaminar embryonic disc into a trilaminar embryonic disc. The end product is the formation of the three primary germ layers within the developing embryo.[1] They are the endoderm, ectoderm, and mesoderm. The yolk sac is endodermal in origin. The endoderm gives rise to the respiratory and gastrointestinal tubes and their visceral organs, such as the lungs, liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. The ectoderm gives rise to many outer body tissues such as the epidermis, sweat, mammary glands, lens, cornea, and nasal and oral epithelial linings. The neural tube and neural crest also derive from the ectoderm. The mesoderm gives rise to muscles, connective tissue, the cardiovascular and lymphatic systems, and organs such as the spleen and kidneys.[2] See Image. Embryology, Human Embryo.

The yolk sac disappears near the end of the first trimester and eventually becomes sonographically undetectable, beginning around the 14th week of gestation.[3]

Cellular

The yolk sac gives rise to primordial germ cells, which develop in the embryo and eventually become ovaries or testes in the fetus. A yolk sac tumor, also known as an endodermal sinus tumor, is a rare but highly malignant tumor of these germ cells. Both children and adults may develop yolk sac tumors, but the incidence is higher in children. A yolk sac tumor is the most common testicular tumor in young children and infants. Yolk sac tumors are well-circumscribed. They produce alpha-fetoprotein, which can support the diagnosis if found to be elevated. On histology, perivascular structures called Schiller-Duval bodies are seen in yolk sac tumors and are pathognomonic if present. They appear as perivascular bodies with tumor cells organized around a blood vessel.[4]

The erythro-myeloid progenitors (EMPs) are present in the yolk sac, from which the macrophages will derive.

Biochemical

The biochemical process of hematopoiesis begins in the yolk sac; this is how the developing embryo can produce red and white blood cells and platelets. The primitive hematopoietic system is hypothesized to involve a sequential migration of hematopoietic stem cells. They travel from the yolk sac to the liver and later the liver to the bone marrow. The hematopoietic stem cells of adults are in the bone marrow.

The yolk sac contains cells that are CD34+, a nonspecific antigen associated with hematopoiesis. Researchers have observed these CD34+ cells in the bone marrow during the 14th week of gestation, further supporting this hypothesis of the migration of hematopoietic stem cells.[5]

Molecular Level

During the second week of embryonic development, implantation occurs, and the conceptus is referred to as the blastocyst, which contains the inner cell mass. The inner cell mass is an early derivative of the embryo. The blastocyst begins organizing itself into four extra-embryonic membranes. These are called the yolk sac, amnion, chorion, and allantois. Each membrane provides a supportive role for the developing embryo. The yolk sac, or umbilical vesicle, is the first of the extra-embryonic membranes to appear.

The inner cell mass begins to form a bilaminar embryonic disc with different cells on each side. Ventrally, hypoblast cells line the bilaminar disc and proliferate to form the yolk sac, the extra-embryonic membrane that sits in the cavity of the blastocyst. The yolk sac also gives rise to the allantois at three weeks post-fertilization (five gestational weeks). The allantois is a tubular outpouching of the yolk sac that is involved in removing nitrogenous waste products and is associated with the development of the urinary bladder. The allantois connects the dome of the bladder to the yolk sac during fetal development. The allantois begins to involute during the 4th and 5th months of pregnancy, forming the urachus. The lumen of the urachus eventually closes after birth, which prevents further communication between the bladder and umbilicus. Subsequently, the urachus becomes the median umbilical ligament, a fibrous supportive structure that extends internally from the bladder to the umbilicus.[6]

The chorion also develops from the yolk sac and functions to nourish the developing embryo. It also produces chorionic fluid, which is essential for cushioning and protecting the embryo. Furthermore, due to its vascularity, the chorion is involved in gas and nutrient exchange. Its chorionic villi can extend and contact maternal blood vessels since it is the outermost layer of the extra-embryonic membranes. The villi also contribute to the formation of the placenta.

The dorsal side of the bilaminar disc contains cells of the epiblast, which form the amnion, another extra-embryonic membrane. The amnion resides in the amniotic cavity. The process of amnion formation also occurs during the second week of development. The amnion is responsible for surrounding the embryo with amniotic fluid, which supports the development and movement of the embryo.

Function

The yolk sac is responsible for critical biological functions during early gestation. Before the placenta forms and can take over, the yolk sac provides nutrition and gas exchange between the mother and the developing embryo. It is also the main organ of embryonic blood cell production via blood islands near the yolk sac. Primitive hematopoiesis occurs in the yolk sac before the liver and bone marrow sequentially take over. Other functions of the yolk sac include the production of stem cells and primitive macrophages, the production of germ cells, metabolic regulation, and the synthesis of proteins such as albumin, alpha-fetoprotein, and apolipoproteins. The yolk sac also contributes to the formation of the umbilical cord.

Mechanism

Embryogenesis entirely depends on the vascular system of the yolk sac, also known as vitelline circulation. Vitelline circulation refers to the bidirectional blood flow between the yolk sac and embryo, which is critical for nutrient exchange until the full establishment of placental function. The yolk sac contains an extensive capillary plexus for absorbing nutrients and oxygen that pass on to the embryo. The primitive aorta supplies blood to the yolk sac, where this absorption occurs at the capillaries, and then the vitelline veins drain and direct blood to the embryo.[7]

Testing

The yolk sac is clinically significant as it is the first structure that is visible sonographically during pregnancy. Clinicians can detect the yolk sac on transvaginal ultrasound starting at five weeks post-fertilization. The gestational sac refers to the round, fluid-filled pouch within the uterus surrounding the developing embryo and yolk sac. On transvaginal ultrasound, the gestational sac appears as a round or oval structure surrounded by a smooth, circular, and echogenic lining. The yolk sac appears as a round, hypoechoic structure inside the gestational sac with surrounding walls that are echogenic. See Image. Gestational Sac. Normal yolk sac size ranges from 3 mm to 5 mm, and the normal shape is circular.

A normal yolk sac seen on ultrasound confirms that the pregnancy is viable and intrauterine. If a yolk sac is not visible, the pregnancy is not viable, or the gestational age may be incorrect. The recommendation is that clinicians repeat the transvaginal ultrasound 1 to 2 weeks later. For example, if the patient does not remember the date of her last menstrual period, the yolk sac may not be visible due to her actual gestational age being less than five weeks post-fertilization (seven gestational weeks). Having a history of irregular menstrual cycles may also cause inaccurate dating of gestational age.[8]

Underlying maternal conditions and factors that may cause irregular menstrual cycles are broad. They include polycystic ovarian syndrome, diabetes, systemic lupus erythematosus, immature hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, endometriosis, thyroid disorders, and eating disorders.[9]

Pathophysiology

During the sixth to tenth weeks post-fertilization, physiologic herniation and rotation of the embryonic bowel occur at the midgut. Herniation of the midgut involves the projection of the embryologic bowel into the developing umbilical cord within the yolk stalk, or vitelline, omphaloenteric, or omphalomesenteric duct. At the base of the umbilical cord, the midgut undergoes two episodes of physiologic rotation. Initially, the midgut rotates 90 degrees counterclockwise using the superior mesenteric artery as an axis. The midgut then returns to the abdomen as the abdominal cavity has enlarged. The second rotation is 180 degrees counterclockwise and takes place around ten weeks post-fertilization. In total, 270 degrees of rotation occur. This herniation occurs due to a lack of space inside the abdominal cavity. The fetal midgut, kidneys, and liver are large at this time. The abdominal cavity, however, grows at a much slower rate than the midgut. Herniation allows the midgut enough space to grow rapidly outside of the peritoneum in the extra-embryonic coelom. Upon completion of herniation and rotation, the yolk stalk degenerates. Degeneration commonly occurs in the seventh week of gestation.

The yolk stalk is connected to the midgut prior to herniation and is commonly referred to as the vitelline duct by clinicians. In approximately 2% of people, the vitelline duct fails to degenerate and persists. This outcome results in a gastrointestinal outpouching called Meckel's diverticulum, characterized by a complete or partial opening between the umbilicus and the bowel. Meckel's diverticulum is the most common congenital abnormality of the gastrointestinal tract. In its classically described form, it sits within 2 feet of the ileocecal valve and measures approximately 2 inches long. However, Meckel's diverticulum is highly variable in appearance, and it may be asymptomatic or manifest as symptoms of its heterotopic gastric or pancreatic mucosa that are often present. For example, as heterotopic gastric mucosa produces acid in the bowel, it may cause gastrointestinal bleeding, ulcers, and eventual perforation if left untreated.[10]

A patent urachus is a rare congenital anomaly in which the urinary bladder remains connected to the outside world via the umbilicus. This occurs due to a failed involution of the urachus. It often presents in neonates with urine leakage from the umbilicus after birth. If the urachus only partially involutes, a fluid-filled urachal cyst is formed. Complications of urachal anomalies include infection, urachal neoplasms, stone formation, and umbilical granulomas.[6]

Clinical Significance

The gestational sac and yolk sac are the first abnormal structures identifiable during a spontaneous abortion, a term synonymous with miscarriage or pregnancy loss. More specifically, an abnormal yolk sac is identifiable on ultrasound at least seven days before a spontaneous abortion, most of which occur during the first trimester. This finding is crucial for effectively managing and counseling patients during a spontaneous abortion.[3]

During the first trimester, sonographic findings of the yolk sac give clinicians important information in terms of pregnancy outcomes. Absent, small, and large yolk sacs are associated with pregnancy loss compared to yolk sacs of pregnancies that continue past the first trimester.[3] A yolk sac is defined as small or large when it falls below the fifth percentile or surpasses the 95th percentile, respectively, for the expected size. Measurements of the yolk sac merit consideration in addition to growth percentiles. Defined abnormal measurements are less than 3 mm or greater than 6 mm in size. Small and large yolk sacs have both correlated with spontaneous abortions. Other abnormal ultrasound findings associated with spontaneous abortions include irregularly shaped and calcified yolk sacs. It is important to note that an abnormal yolk sac finding does not always indicate spontaneous abortion. Although uncommon, viable pregnancies can occur with oval-shaped and enlarged yolk sacs.[8] Some studies have found abnormal yolk sac shape to be more specific for spontaneous abortion than abnormal size, although both are considered strong predictors.[11]