Introduction

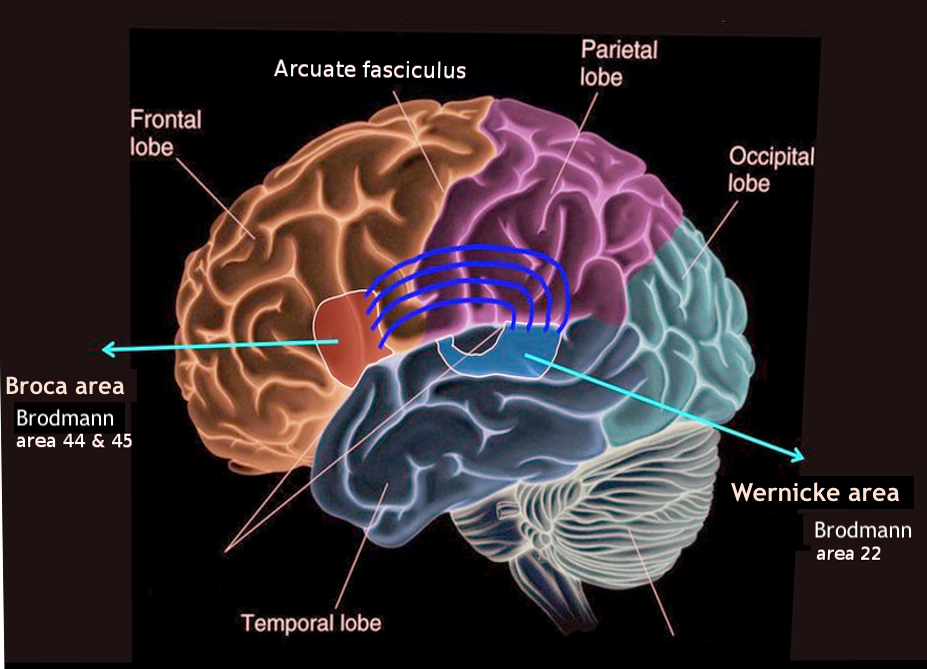

Wernicke area was first discovered in 1874 by a German neurologist, Carl Wernicke. It has been identified as 1 of 2 areas found in the cerebral cortex that manages speech. Wernicke area is located in Brodmann area 22, the posterior segment of the superior temporal gyrus in the dominant hemisphere.[1] Since 95% of people have a left dominant hemisphere, the Wernicke area is usually found on the left side. This area encompasses the auditory cortex on the lateral sulcus. Contrast this with Broca's area which is found in the inferior frontal gyrus right above the Sylvian fissure.[2] Because the Wernicke area is responsible for the comprehension of written and spoken language, damage to this area results in a fluent but receptive aphasia.

Receptive aphasia may be best described as one who is unable to comprehend/express written or spoken language. The patient will most commonly have fluent speech, but their words will lack meaning. The other aspect of Wernicke aphasia is that the patient has auditory incomprehension. This means an individual is unable to understand what is being spoken to them. Lastly, patients with Wernicke aphasia are unaware of their lack of comprehension. Due to the prominent involvement of the Wernicke area in basal life, various disease etiologies may result in damage to this area.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Wernicke area receives its vascular supply from the inferior temporal branch of the middle cerebral artery. The temporal lobe drains blood via 2 primary routes.

The first involves the anterior drainage of the temporal lobe via the superficial middle cerebral vein. As it is drained, it progresses toward the vein of Labbe which eventually empties into the transverse sinus.

The second route involves drainage of the inferior temporal love into the posterior choroidal vein. From there, it moves posteriorly behind the interventricular foramen to join with the thalamostriate vein and form the internal cerebral vein. The internal cerebral vein then joins the basal veins to form the great cerebral vein.

Muscles

Although the result of all speech production is a series of muscle movements, new research demonstrates that the neurologic mechanisms involved in speech production are not simply limited to motor commands that move muscles. Before motor commands can be sent, the speaker must create a mental image of the sounds comprising the words. This stage can be exemplified by the fact that one knows that the word “snow” rhymes with “blow” but not with “flow” without needing to say these words aloud.[3] A disruption of this contemplative retrieval process results in the improper displacement of spoken words. This phenomenon is a cardinal feature of both Wernicke and Broca aphasia. As Wernicke aphasia is most commonly associated with solely comprehensive deficits, impairment in speech production remains a steady component as well. Newer imaging studies have shown that the Wernicke area may indeed have a broader location in the temporal lobe. As it has always been known that damage to Wernicke area results in receptive aphasia, this is not always the case. Some individuals use the right hemisphere for language, and isolated damage to Wernicke area that spares the white matter may not cause severe receptive aphasia.

Surgical Considerations

The temporal lobe is a crucial component in regulating essential processes such as language, memory, and emotion. Thus, surgery must be performed with extreme care to avoid detrimental results. Because temporal lobe surgery commonly has more risks than benefits, it is mainly reserved to treat temporal lobe epilepsy.

Clinical Significance

Wernicke area is most commonly damaged due to vitamin B1 (thiamine deficiency) resulting in Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. While most often associated with chronic alcoholism, Wernicke encephalopathy may also occur due to poor nutrition, increased metabolic requirement, or in the setting of renal dialysis (water-soluble vitamin depletion).[4] Recent statistics showed that 12.5% of patients at autopsy with a history of chronic alcoholism showed Wernicke encephalopathic lesions. Wernicke lesions may consist of vascular congestion, petechial hemorrhages, and microglial proliferation. Chronic cases also include gliosis, demyelination, and loss of neuropil with relative preservation of neurons. Although neuronal loss is most prominent in the relatively unmyelinated medial thalamus, atrophy of the mammillary bodies is the most specific finding associated with Wernicke encephalopathy.

Wernicke Syndrome

The cardinal symptoms of Wernicke syndrome include gait ataxia, horizontal nystagmus, and encephalopathy. The encephalopathy may be characterized by inattentiveness, delirium, and profound disorientation to person/place/time. Although horizontal nystagmus is the most common ocular finding, vertical nystagmus may also occur. The ataxia experienced in these patients is a combination of vestibular dysfunction, cerebellar involvement, and polyneuropathy. Other uncommon findings may include severe hypotension, hypothermia, or coma.

Korsakoff Syndrome

Korsakoff syndrome has a more chronic onset and is characterized by confabulation, memory loss, hallucinations, and personality changes. Diagnostic imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to illustrate contrast enhancement in the mamillary bodies and thalamus.[5] A strong precipitating factor of the encephalopathy is the administration of glucose before thiamine in these patients. For this reason, it is extraordinarily important to administer thiamine to patients presenting with alcohol abuse symptomology.

Hyperemesis Gravidarum

During pregnancy, expecting mothers may experience a phenomenon labeled as hyperemesis gravidarum. Over 75% of pregnant women experience severe nausea and vomiting during the first and second trimester of pregnancy. When vomiting becomes severe enough to result in weight loss, it is termed hyperemesis gravidarum. In addition to the variety of electrolyte abnormalities experienced, Wernicke encephalopathy may emerge due to water-soluble vitamin deficiency (Thiamine).

Brodmann Area 22 Damage

Wernicke area may be directly damaged via direct insult to the superior temporal gyrus. These etiologies may include transient ischemic attack (TIA), stroke, cerebral abscess, neoplasm, encephalitis, or seizures. Common presentations of patients with damage to this area include a variety of paraphrastic errors in which either whole-word is improperly substituted (chair for table) or phonemic substitutions such as "cable" for "table." Comprehension may be assessed by giving a series of commands with increasing difficulty. The token test is frequently used in which a series of commands involving 20 tokens of different shapes, sizes, and colors presented in increasing complexity. An impairment in comprehension may be due to failure of word recognition, auditory memory, syntactic structure formation, or speech sound discrimination.[6]