Continuing Education Activity

Volvulus occurs when a segment of the intestine twists around itself and its supporting mesentery, causing bowel obstruction and potentially cutting off the blood supply, which can lead to bowel ischemia. The condition presents with symptoms such as abdominal distension, pain, vomiting, constipation, and possibly bloody stools. If untreated, volvulus can progress to bowel necrosis. Colonic volvulus, particularly affecting the sigmoid and cecum, is a potentially life-threatening condition requiring prompt diagnosis and intervention. While some cases, like sigmoid volvulus, may be treated with non-surgical methods like decompression with a rectal tube, cecal volvulus often necessitates surgical intervention.

In this course, participants learn how to effectively evaluate and manage colonic volvulus, including the different treatment modalities based on the volvulus type. The course emphasizes the importance of timely surgical intervention to prevent recurrence and complications. Also highlighted is the critical role of an interprofessional team—including surgeons, radiologists, and gastroenterologists—in the diagnostic process, patient monitoring, and post-surgical care. This collaborative approach is essential for optimizing patient outcomes and reducing the risk of recurrence or complications.

Objectives:

Screen for risk factors that predispose patients to colonic volvulus, such as chronic constipation and prior abdominal surgery.

Differentiate between sigmoid volvulus and cecal volvulus to determine the appropriate treatment approach.

Identify the clinical signs and symptoms of colonic volvulus, including abdominal distension, pain, and potential bowel obstruction.

Communicate the importance of coordination among the interprofessional team for prompt diagnosis and treatment of volvulus to improve outcomes for the affected patients.

Introduction

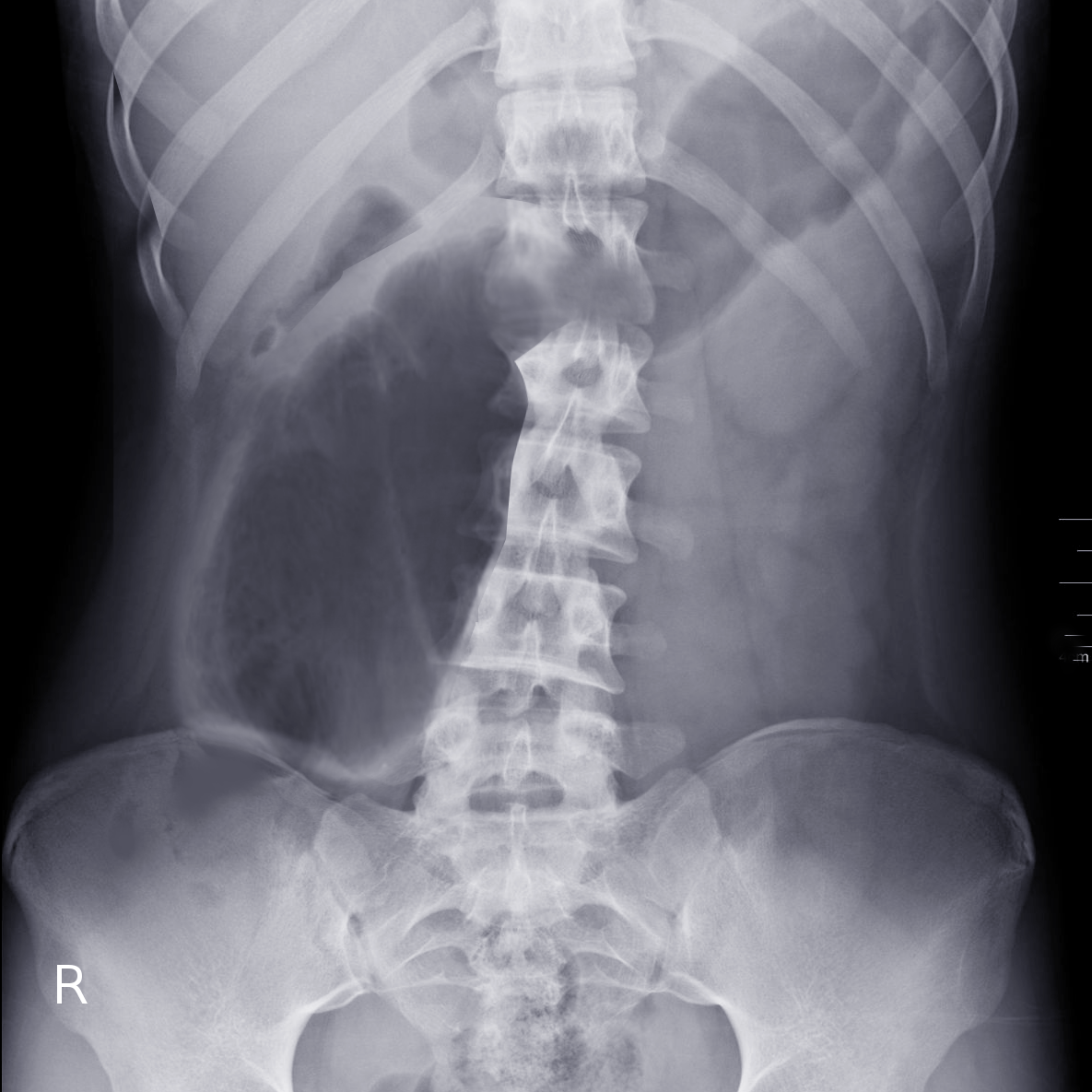

Volvulus occurs when a loop of intestine twists around itself and the mesentery that supplies it, causing a bowel obstruction. Symptoms include abdominal distension, pain, vomiting, constipation, and bloody stools. The onset of symptoms may be insidious or sudden. The mesentery becomes so tightly twisted that the blood supply is cut off, resulting in bowel ischemia. Pain may be significant, and fever may develop (See Image. Cecal Volvulus).

Risk factors for volvulus include intestinal malrotation, Hirschsprung disease, an enlarged colon, pregnancy, and abdominal adhesions. A higher incidence of volvulus is also noticed among hospitalized individuals with neuropsychiatric disorders such as Parkinson disease or multiple sclerosis. High fiber diet, chronic constipation with chronic use of laxatives and/or enema, and associated myopathy like Duchene muscular dystrophy are also associated with an increased risk of sigmoid volvulus. In adults, the sigmoid colon and cecum are the most commonly affected. On the contrary, splenic flexure is least prone to volvulus. In children, the small intestine and stomach are more commonly involved. Diagnosis is mainly clinical; however, characteristic radiological findings on plain radiographs, ultrasound, and upper gastrointestinal series help differentiate from other differentials (See Image. Cecal Volvulus Radiograph).[1] The present topic covers volvulus in adults with specific differences from midgut volvulus in children. However, a detailed discussion of malrotation and midgut volvulus is beyond the scope of this topic.

Sigmoidoscopy or a barium enema can be attempted as an initial treatment for sigmoid volvulus. However, due to the high risk of recurrence, bowel resection with anastomosis within 2 days is generally recommended. If the bowel is severely twisted or the blood supply is cut off, emergent surgery is required. In a cecal volvulus, part of the bowel is usually removed. The cecum may be returned and sutured in place if it is still healthy. However, conservative treatment in both cases is associated with high recurrence rates.

Etiology

Volvulus is associated with intestinal malrotation, an enlarged colon, a long mesentery, Hirschsprung disease, pregnancy, abdominal adhesions, and chronic constipation. In adults, the sigmoid colon is the most commonly affected part of the gut, followed by the cecum. In children, the small intestine is more commonly involved.[2] In most cases, sigmoid volvulus is an acquired disorder. On the other hand, cecal volvulus may occur due to incomplete dorsal mesenteric fixation of the right colon or cecum or an elongated mesentery. Sigmoid volvulus is more common in individuals with neuropsychiatric disorders, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinsons disease.

Neuroleptic drugs can also interfere with colonic motility and may trigger volvulus. Nursing home patients who are bedridden and have chronic constipation have a greater risk of developing sigmoid volvulus. A higher incidence of volvulus is also noticed among patients with associated myopathy like Duchene muscular dystrophy or visceral myopathy. In developing countries, a high-fiber diet leads to overloading of the sigmoid colon, causing it to twist around the mesentery. Similarly, Chagas disease or megacolon can also predispose to sigmoid volvulus. Rarely, appendicitis or surgery may lead to excessive adhesions leading to volvulus.

Epidemiology

Colonic volvulus constituted nearly 2% of all the cases of bowel obstructions admitted in the United States between 2002 and 2010. Sigmoid volvulus, accounting for 8% of all intestinal obstructions, occurs between the third and the seventh decades of life. This condition is more frequent in older men, Black individuals, adults with chronic constipation, and those with associated neuropsychiatric disorders. On the other hand, cecal volvulus is more common in younger women.[3] The age group of midgut volvulus is strikingly different from colonic volvulus; it is typically seen in babies with rotation anomalies of the intestine. Segmental volvulus of other gut portions can occur in people of any age, usually because of abnormal intestinal contents or adhesions.

Pathophysiology

Sigmoid volvulus is typically caused by 2 mechanisms: chronic constipation and a high-fiber diet. In both instances, the sigmoid colon becomes dilated and loaded with stools, making it susceptible to torsion. The direction of the volvulus is counterclockwise. With repeated attacks of torsion, there is a shortening of mesentery due to chronic inflammation. Subsequently, adhesions develop, which then entrap the sigmoid colon into a fixed twisted position. Cecal volvulus can be either organoaxial (cecocolic or true cecal volvulus) or mesentericoaxial (cecal bascule). In the organoaxial variety, the ascending colon and distal ileum twist around each other clockwise. However, in the mesentericoaxial sub-type, the caecum is not completely fixed and is located anteriorly over the ascending colon at a right angle to the mesentery. Since there is no twisting of the vascular pedicle, vascular compromise is rarely associated with cecal volvulus.[4] In contrast to colonic volvulus, midgut volvulus in children is invariably due to rotation anomalies of the intestine.[5]

History and Physical

Patients with sigmoid volvulus are usually older adult men with a history of chronic constipation. Although most patients have an acute onset of symptoms, nearly one-third may have an insidious presentation. Signs and symptoms of volvulus include abdominal pain, distension, vomiting, constipation, obstipation, hematochezia, or fever.[6] Patients presenting to the hospital after a significant delay may have diffuse tenderness, guarding, and rigidity, suggesting perforation peritonitis. In severe abdominal distension, patients often develop hemodynamic instability and respiratory compromise. In contrast, newborns with midgut volvulus have sudden onset bilious emesis, upper abdominal distension, hematochezia, or inconsolable crying. Older children with midgut volvulus may also present with features including episodic abdominal pain, diarrhea, and failure to thrive.[5]

Evaluation

Diagnosis of colonic volvulus is clinical; however, radiological investigations are often required for diagnostic confirmation due to overlapping clinical features with other diseases. The first investigation to be performed is a plain radiograph of the abdomen. Specific signs, including a "bent inner tube" or a "coffee bean" sign, are characteristics of sigmoid volvulus. These refer to the appearance of the air-filled closed loop of the colon, which forms the volvulus, revealing a thick inner and a thin outer wall. Similarly, plain radiographs of cecal volvulus patients reveal distended small and large bowel. Contrast enema should be performed only after perforation peritonitis is ruled out. Demonstration of a "bird's beak" at the point where the colon rotates to form the volvulus is characteristic of sigmoid volvulus.

Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis is generally not indicated in patients with colonic volvulus, however, when performed an upward displacement of the appendix with large and small bowel obstruction is suggestive of cecal volvulus.[7] Similar to colonic volvulus, in children with midgut volvulus, radiological features include a paucity of gas throughout the intestine with few scattered air-fluid levels on plain radiograph and an abnormally placed duodenojejunal junction with the small bowel looping entirely on the right side of the abdomen on upper gastrointestinal series.[5] Laboratory studies, including complete blood count and serum biochemistry, may show a left shift with leucocytosis and electrolyte abnormalities. However, these are non-specific.

Treatment / Management

In all the cases of volvulus, patients need to be resuscitated before surgery. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should also be administered in these patients preoperatively. Vitals monitoring, including measurement of the urine output, should be done periodically. Some clinicians also advocate nursing the patient in a left lateral position to avoid compression over the vena cava. The initial treatment for sigmoid volvulus is sigmoidoscopy, which can also help in establishing a diagnosis of sigmoid volvulus. Spiraling of the mucosa and difficulty negotiating the scope beyond the site of obstruction are classical features of sigmoid volvulus on sigmoidoscopy.[8] For endoscopic treatment, gentle insertion of the endoscope just below the site of torsion and air insufflation is attempted. If unsuccessful, the endoscope tip can be used to follow the twisted mucosa and reach the apex. Alternatively, a soft flatus tube or red rubber tube can be inserted. This leads to detorsion and decompression. The success rate of sigmoidoscopic reduction lies between 50% to 100%.[8] A flatus tube is kept in situ after the endoscopic reduction to prevent an early recurrence. Due to a high recurrence rate, a bowel resection within 2 days is recommended. Contraindications to endoscopic reduction include suspicion of bowel gangrene manifesting as fever, persistent hematochezia and features of sepsis, and perforation peritonitis. Immediate resuscitation and surgery are recommended in these cases.

Surgical options for sigmoid volvulus include bowel resection and bowel conservative surgery. Bowel resection is recommended over conservative surgery (sigmoidopexy or mesenteric plication) as recurrence rates are higher with the latter. If there is no faecal peritonitis, a primary resection can be done. If there is bowel perforation, then a Hartmann procedure can be performed. A minimally invasive approach for sigmoid volvulus can be considered depending on the surgeon's preference and experience. Older adult patients may benefit from minimally invasive procedures.[9]

Endoscopic decompression for cecal volvulus has low success rates (nearly 20%) and is also associated with high recurrence rates. In a cecal volvulus, the cecum can be detorsed and cecopexy can be performed. However, a part of the cecum often needs to be removed. The ideal procedure for cecal volvulus right hemicolectomy. If the bowel is necrotic, then resection with an ileostomy or a colostomy is necessary. If the patient is critically ill and is not fit for general anesthesia, a percutaneous tube cecostomy can be performed as an interim procedure. A definite procedure can be attempted when the anesthesia team declares the patient fit.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for volvulus include the following:

- Abdominal hernia

- Appendicitis

- Acute mesenteric ischemia

- Colon cancer

- Constipation

- Colonic polyps

- Diverticulitis

- Intestinal perforation

- Intestinal pseudo-obstruction

- Intussusception

- Megacolon, chronic

- Megacolon, toxic

- Mesenteric artery ischemia

- Ogilvie syndrome

- Pseudomembranous colitis

- Rectal cancer

Prognosis

Any delay in the diagnosis of cecal or sigmoid volvulus can be associated with high morbidity and mortality. Mortality rates appear to be much higher for cecal volvulus than sigmoid volvulus. When volvulus is treated non-surgically, recurrence rates are very high, approaching 40% to 60%. When surgery is done in unstable patients, mortality rates of 12% to 25% have been reported.

Complications

If untreated, volvulus can cause bowel strangulation, gangrene, perforation, and peritonitis. Complications of surgery include the following:

- Recurrence (if conservative surgery is performed)

- Anastomotic leak

- Wound infection

- Pelvic abscess

- Sepsis

- Fecal fistula

- Complications of colostomy and/or ileostomy

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Resumption of the enteral feeds may be delayed in some patients, especially those having perforation peritonitis or those who had undergone resection of the necrotic bowel with anastomosis. In these conditions, a nasogastric tube provides optimal bowel decompression. Total parenteral nutrition can be considered in patients who require prolonged fasting due to resection of a major proportion of the small bowel. Colostomy and/or ileostomy care must be taught to the patients and their relatives.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The older adult population must be taught the risk factors associated with colonic volvulus. These include chronic constipation, high-fiber diet, chronic dependence on enemas or laxatives, association with neuropsychiatric disorders and myopathies, and the use of neuroleptic drugs. Similarly, Chagas disease or megacolon can also predispose to sigmoid volvulus. Rarely, appendicitis or surgery may lead to excessive adhesions leading to volvulus. Patients must also be informed about the available treatment options, including conservative strategies and complications. A need for enterostomy (colostomy and /or ileostomy) must always be explained to the patients before the surgery for volvulus.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with volvulus often present to the emergency department. While the diagnosis is not difficult, the management is not always straightforward. Thus, involving an interprofessional team is important. Involving the radiologist immediately so that a diagnosis can be made urgently. Monitoring the patient before and after the surgery is exceedingly important and must be done in the intensive care unit or high-dependency unit under the care of an intensivist. Immediate consultation with a surgeon is necessary to plan for surgery. The role of a gastroenterologist is also vital, as immediate treatment of sigmoid volvulus is detorsion utilizing the sigmoidoscopic reduction technique. In the postoperative period, clinicians should provide prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis, pressure ulcers, and gastritis. Clinicians also play a critical role in educating patients and their relatives about stoma care. Open communication between the team is vital to achieve good outcomes.