Continuing Education Activity

A left ventricular aneurysm is one of the worst complications after acute myocardial infarction. The natural course leading to the formation of a ventricular aneurysm involves a full-thickness infarct that has been replaced by fibrous tissue. This inert portion cannot take part in the contraction and herniates outward during systole. Most of the LV aneurysms are asymptomatic and are found in follow-up echocardiography. However, large symptomatic LV aneurysms can cause heart failure, ventricular tachyarrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death. LV aneurysms are manageable through medical treatment directed towards its complications with anticoagulation, surgical resection of an aneurysm in a large aneurysm, valvular dysfunction, or worsening complications. This activity reviews the role of an interprofessional team in the diagnosis and treatment of LV aneurysms.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of a ventricular aneurysm.

Outline the appropriate evaluation of ventricular aneurysm.

Review the management options available for the ventricular aneurysm.

Describe interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to manage ventricular aneurysms and improve outcomes.

Introduction

About 1.5 million patients develop acute myocardial infarction per year in the United States.[1] Several complications, such as ischemic, mechanical, arrhythmic, embolic, or inflammatory complications, are associated with acute myocardial infarction. The development of mechanical complications after acute myocardial infarction is associated with significantly reduced short-term and long-term survival.[2] One of the most common complications occurring post-infarction is a ventricular aneurysm. LV aneurysm was first reported in 1951 by angiographic evidence. The term aneurysm applies to the bulging or outpouching of the weakened muscle wall. The natural course leading to the formation of a ventricular aneurysm involves a full-thickness infarct that has been replaced by fibrous tissue. This inert portion cannot take part in the contraction and herniates outward during systole. It leads to an expansion of a dyskinetic area and forms a thin circumscribed, fibrous and noncontractile outpouching.

A significant left ventricular (LV) aneurysm is present in 30% to 35% of acute transmural myocardial infarction.[3] The two major risk factors for developing LV aneurysm include total occlusion of the left anterior descending artery and failure to achieve patency of infarct site artery.[4] Ventricular aneurysms can be true or false aneurysms.[5] A true aneurysm is formed by full-thickness bulging of the ventricular wall. In contrast, a false ventricular aneurysm is formed by the rupture of the ventricular wall, which is contained by the surrounding pericardium. The inferior and anterior myocardial infarctions occur with almost equal frequency. It explains 85% of a true LV aneurysms location at the apical and anteroseptal wall. The incidence of an inferior-posterior or lateral wall aneurysm is very low, about 5% to 10%. This preference for the apical site may be explained because there are only three layers of muscle at the apex compared with four layers at the base. False aneurysms tend to involve the posterior or diaphragmatic surface more commonly than the apical or lateral wall. Most of the ventricular aneurysms are asymptomatic and are evident during routine diagnostic procedures. However, LV aneurysm symptoms can range from thromboembolic, arrhythmic, wall motion abnormalities, reinfarction, ventricular tachyarrhythmias, and risk of sudden cardiac death.

Etiology

Schlichter et al. (1954) described in detail the etiological causes of ventricular aneurysms. The etiology of LV aneurysm is classified as follows:

- Congenital aneurysm: It is a sporadic type in either of the ventricles. These aneurysms are usually large and lined with thin fibrous tissue. They have broad-based communication with the ventricular cavity and contain unclotted blood.[6]

- Acquired aneurysm: which can be classified into[7]:

- Ischemic: Almost 85% to 90% of the ventricular aneurysms occur in the setting of acute anterior wall myocardial infarction.

- Traumatic: They occur as a result of either accidental or surgical wounds.

- Infective: Common causes include infective endocarditis, rheumatic fever, syphilis, tuberculosis, septic emboli, polyarteritis nodosa, etc.

- Idiopathic: A ventricular aneurysm of unknown etiology usually occurs in Africans and occasionally in the white population. It is an unusual aneurysm often arising close to the mitral ring in the form of an annular subvalvular aneurysm. It stretches the mitral ring and interferes with the function of the papillary muscle, chordae tendinae, and cusps of the mitral valve.

- Postpartum: Rarely left ventricular aneurysm can be seen secondary to postpartum cardiomyopathy.

- Other causes: systemic hypertension, steroids, and NSAIDs use may predispose to aneurysm formation. Other causes include Chagas disease, sarcoidosis, etc.

Epidemiology

In the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS), 7.6% of patients had a left ventricular aneurysm in a total population of 15000 patients. The LV aneurysm was found in 22% of the anterior wall myocardial infarction within 3 months of infarction. Ventricular wall aneurysm is associated with high cardiac mortality that can be around 67% and 80% for 3 months and 1 year, respectively.[8]

Pathophysiology

The transmural myocardial infarction due to the occlusion of either the left anterior descending artery or the dominant right coronary artery leads to the formation of a true left ventricular aneurysm. Two principal mechanisms are involved in its formation, the early expansion phase, and the late remodeling phase.[9]

Early Expansion Phase

A true left ventricular aneurysm following acute myocardial infarction can occur as early as 48 hours or two weeks post-infarction.

Within hours of the infarction, the gross thinning of the infarct zone occurs. The migration of inflammatory cells in the infarct zone occurs by 2 to 3 days post-infarction. They contribute to the lysis of the necrotic myocytes by 5 to 10 days. Some viable myocytes are often present in the infarct area. There is a disruption of the collagen fibers, and along with the necrotic myocytes, it forms the nadir of myocardial tensile strength. Usually, in the infarcted zone, an extravascular hemorrhage can occur, leading to the decreased diastolic and systolic function of the heart. The factors contributing to the formation of the left ventricular aneurysm in the early phase include:

- Preserved contractility of the surrounding myocardium

- Transmural infarction

- Lack of collateral circulation

- Lack of reperfusion

- Elevated wall stress

- Hypertension

- Ventricular dilatation

- Wall thinning

Late Remodeling Phase

About 2 to 4 weeks post-infarction, remodeling of the myocardium begins with the appearance of highly vascularized granulation tissue. It is replaced by fibrous tissue 6 to 8 weeks post-infarction. As the myocardium becomes replaced by fibrous tissue, it greatly decreases the ventricular wall thickness due to the loss of myocytes.

Histopathology

The aneurysmal wall examined at necropsy and in surgical specimens shows aneurysmal wall thickness between 0.3 to 5 mm. The wall is composed almost entirely of fibrous tissue, with a few strands only of elastic tissue and necrotic cardiomyocytes. Also, extensive calcification in the aneurysmal wall is the characteristic finding of a true ventricular aneurysm. The size of the aneurysm varies between 5 x 7 cm and 1O x 15 cm in diameter. The usual site of the aneurysm is anterior, with extension laterally towards the septum, owing to the occlusion of the left anterior descending artery in anterior myocardial infarction. An area of pericarditis is usually noted over the aneurysm. Further, a ventricular aneurysm consists of a laminated mural thrombus and consists of old and recent thrombotic elements.

History and Physical

History

Small aneurysms are usually asymptomatic and are typically diagnosed by routine investigations. However, large aneurysms present with signs and symptoms of thromboembolism, wall motion abnormalities, contractility defects, arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death. Common symptoms associated with the ventricular aneurysm include:

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Palpitations

- Syncope

- Fluid retention causes swelling of ankles, feet, or abdomen

- Stroke, or thromboembolic phenomenon to any organ in the body

- Limb or visceral ischemia

Physical Exam

Clinical examination of the cardiovascular system reveals abnormalities pertinent to associated complications with the ventricular aneurysm. The physical signs which should suspect the presence of ventricular aneurysm include:

- Tachycardia

- Arrhythmias

- Pericardial rub

- Abnormalities of cardiac impulse

- Paradoxical splitting of the S2

- S3 heart sound

- Pedal edema

- Fine inspiratory basal crept

- Murmurs

Complications

The following complications can occur after an LV aneurysm.[10]

Heart Failure and Ischemia

The LV dilation, paradoxical motion, and high end-diastolic pressure due to aneurysm result in ischemia and heart failure secondary to cardiac output loss. The long-standing volume overload can further cause worsening of LV aneurysm entering a loop that enforces worsening heart failure and ischemia with worsening LV aneurysm.

Ventricular Arrhythmias

The LV aneurysm can generate severe ventricular tachyarrhythmias leading to sudden cardiac death. The fibrous tissue at the LV aneurysm site or the transition zone of normal myocardium and the aneurysmal wall can be arrhythmia focus.

Thromboembolization

Stasis of blood at the aneurysmal site can increase the formation of a mural thrombus that can eventually dislodge and put the patient at risk of embolization to body organs, including the brain, to cause a stroke.

Ventricular Rupture and Cardiac Tamponade

Mature LV aneurysms have fewer chances of rupture due to dense fibrous tissue, but early immature aneurysms can rupture with the potential to cause cardiac tamponade and shock.

Evaluation

The evaluation can include the following diagnostic testings: [11]

Routine Investigations

Electrocardiogram

There are three key electrocardiographic features of LV aneurysm after acute myocardial infarction, including 1) Tall R wave in lead AvR known as Goldberger's sign. 2) Persistent ST-segment elevation with T wave inversion. 3) Small R waves in the leads of the distribution of the left ventricular wall. Other EKG findings can include ventricular arrhythmias that can be complications of LV aneurysm.

Chest Radiograph

In an anteroposterior or slightly oblique view of chest x-ray, a ventricular aneurysm forms a well-circumscribed opacity projecting beyond the regular cardiac outline. In contrast, in the lateral view, it forms a rounded or oval shadow, partially or entirely superimposed upon that of the heart.

Computed Tomography

CT scan is another reliable imaging modality for LV aneurysms. Cardiac CT can give a better view of the aneurysm wall and the presence of mural thrombus at the cost of risk of contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN). However, CIN can be prevented by prior hydration before giving contrast. In patients with ischemic heart disease, assessing LV segmental dysfunction in the form of wall-thinning and reduced wall motion is possible with electron-beam CT (EBCT).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The use of MRI as a noninvasive modality for identifying LV aneurysms and assessing resectability makes it a reliable test. For this purpose, dark-blood imaging may be employed to define the anatomy. It helps in delineating the bulging of the aneurysm. The blood pool motion in the aneurysm is characterized by dynamic bright-blood imaging.

Echocardiography

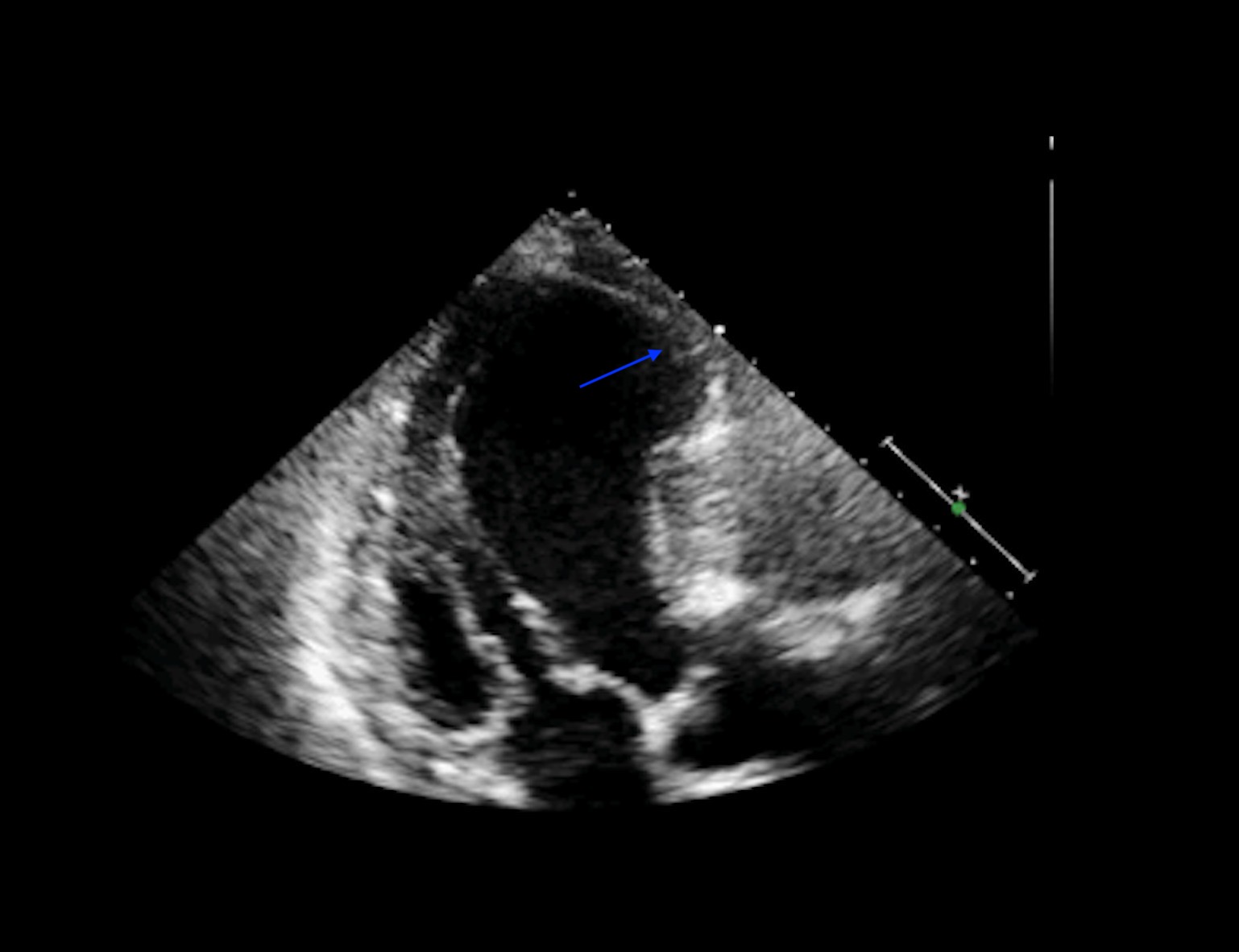

Two-dimensional echocardiography aids in a clear demonstration of a ventricular aneurysm. It may also help differentiate between a true and false type aneurysm by depicting a narrow neck compared to the size of the cavity. Color-flow echocardiographic imaging may identify abnormal flow within the aneurysm. This information may help identify a thrombus. A pulsed Doppler imaging can reveal an oscillatory to and fro motion of aneurysm that changes its variation with inspiration and expiration. Calculating LV systolic function and LV volume is possible with 3-D tomographic echocardiography. An echocardiogram showing a left ventricular aneurysm is seen in figure 1.

Nuclear Imaging

Radionuclide ventriculography may demonstrate a ventricular aneurysm.

Angiography

Left ventriculography has become the "gold standard" and most accurate test for diagnosing and localizing the left ventricular aneurysm site. It demonstrates a large, discrete area of dyskinesia (or akinesia), generally in the anteroseptal-apical walls. Occasionally, left ventriculography also may demonstrate mural thrombus. A quantitative definition of left ventricular aneurysms has been accomplished using a centerline analysis of left ventricular wall motion on left ventriculography in the 30-degree right anterior oblique view. It defines the aneurysm as a hypocontractile segment contracting more than two standard deviations out of the normal range. The outer portion of the aneurysm is termed dyskinetic, and the remaining portion is akinetic. The fraction of the total left ventricular circumference occurring as an aneurysm is calculated as the value percent.

Treatment / Management

The management of LV aneurysms includes medical and surgical.[10]

Medical Management:

Small or medium, or large LV aneurysms with no symptoms can be safely monitored with an expected five-year survival of up to 90%. The management can include optimization of coronary artery disease risk factors for ischemia prevention, afterload reduction with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and anticoagulation to prevent thromboembolism. In patients with large LV aneurysms with symptoms, the management is the same as asymptomatic cases, plus specific treatment for complication/symptoms treatment and perform surgical management if there is any indication. In terms of anticoagulation, the risk of LV mural thrombus is highest within the first month after acute infarction; therefore, it is always prudent to employ anticoagulation in all patients using warfarin the first three months after LV infarction. Long-term anticoagulation should be reserved for patients with large, friable thrombi protruding into the ventricular cavity, documented systemic embolization beyond the three months, or while receiving anticoagulants, and globally impaired LV function.

Surgical Management

Relative indications for ventricular aneurysm operation include:

- Documented expansion

- Large size

- Angina

- Congestive heart failure

- Arrhythmia

- Rupture

- Pseudoaneurysm

- Congenital aneurysm

- Embolism

All patients considered for surgery must undergo right and left cardiac catheterization with coronary arteriography and left ventriculography. An echocardiographic assessment of the mitral valve should be done with +2 mitral regurgitation with cardiac catheterization and should be evaluated for intrinsic valve disease not amenable for annuloplasty. The left ventricular aneurysmal repair constitutes aneurysmectomy, aneurysmorrhaphy, and ventricular restoration that requires cardiopulmonary bypass and a balanced anesthetic technique. The ultimate size of the left ventricular cavity at the end of the procedure is critical to patient outcomes. Using preoperative and postoperative three-dimensional techniques to image the left ventricle, Cherniavsky and colleagues proposed that the aneurysm resection or patch should produce a postoperative left ventricular end-diastolic volume of about 150 mL.

The early surgical approaches, including nondirected aneurysmectomy or infarctectomy with or without revascularization for patients with LV aneurysm and drug-refractory ventricular tachycardia, were abandoned because of high operative mortality. With the advancement of electrophysiologic mapping techniques to demarcate the site of arrhythmogenic focus, a directed subendocardial ablation of the arrhythmia focus of LV aneurysm can be performed. This technique consists of an aneurysmectomy, along with excision of a 2-3 mm thick layer of subendocardial peri-infarcted tissue. With such an approach, tachycardia can be eliminated in 90% of patients with an operative mortality of about 10%.

Relative contraindications for left ventricular aneurysm correction surgery include greater anesthetic risk, myocardial dysfunction, cardiac index less than 2.0 liters/m2 per minute, severe mitral regurgitation, evidence of subendocardial infarction, and lack of a thin-walled aneurysm with prominent margins.

Pseudoaneurysm

Untreated LV pseudoaneurysm can have a mortality of up to 50%. Surgery is the preferred treatment for pseudoaneurysm and holds perioperative mortality up to 10%. Percutaneous transcatheter device closure is preferred over open surgery.[12]

Differential Diagnosis

A ventricular aneurysm can mimic a variety of clinical conditions, which include:

- Angina pectoris

- ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- Left ventricular pseudoaneurysm

- Ventricular wall rupture

- Pericarditis

- Myocarditis

- Cardiac tamponade

- Myocardial trauma

- Takotsubo cardiomyopathy

Prognosis

The natural history and prognosis of ventricular aneurysms are not well defined because most of the reports are based on retrospective data and autopsy studies. In two autopsy studies, in which the age of the aneurysm had to be estimated from a retrospective analysis of case notes, the 5-year mortality rates were 30 and 80%. The most common cause of death was recurrent myocardial infarction and not congestive heart failure. In clinical studies, the prognosis depends on the size of the aneurysm and the presence of symptoms. In the study of Mourdjinis et al., the 5-year mortality was 50% overall, but only 10% in patients with small aneurysms.

In the prospective CASS study, the cumulative 4-year survival rate in patients with angiographic LV aneurysms is 71%. The mortality was dependent on the extent of coronary disease and the degree of LV dysfunction. The presence of an aneurysm per se did not add to the risk of death. Whether surgical intervention with aneurysmectomy alters the natural history or outcome of the condition remains controversial. Large-scale prospective studies comparing conservative and surgical approaches are lacking.

The most recent reported 5-year survival figures following surgery range from 68 to 79%, with only 10% operative mortality. For conservatively treated patients, the survival data at five years is slightly different, ranging from 66.7 to 70%. In the CASS study, the comparison of patients with medically or surgically treated improved survival with surgery was reported only in selected high-risk subgroups, for example, those with triple-vessel disease. This study suggests that survival is determined primarily by revascularization and not aneurysmectomy. Cosgrove et al. demonstrated that the 7-year survival of patients undergoing aneurysmectomy was 65% in those undergoing complete revascularization, compared with 50% for those in whom revascularization was incomplete.

The prospective, randomized STICH (Surgical Treatments for Ischemic Heart Failure) trial may provide more definitive data regarding the effect of surgery for ventricular restoration on survival, ventricular size and function, quality of life, and exercise capacity.

Complications

A left ventricular aneurysm can be associated with a variety of complications such as malignant arrhythmias, heart failure, cardiac ischemia, thromboembolism, and rupture of the ventricle. Almost one-third of the patients with ventricular aneurysms develop arrhythmias. The location of arrhythmogenic focus is usually between that of the normal myocardium and the affected myocardium.[13] This arrhythmogenic focus can be localized with the help of endocardial mapping within 2 cm of the origin. Unfortunately, in patients with polymorphous ventricular tachycardia and after myocardial infarction (within six weeks), the endocardial mapping may fail to localize the site.

The common complications associated with the in-hospital repair of ventricular aneurysm include[14]:

- Low cardiac output

- Ventricular arrhythmias

- Respiratory failure

- Bleeding

- Dialysis-dependent renal failure

- Stroke

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Critical care is a complex and dynamic endeavor for cardiac surgical patients. Successful outcomes after cardiac surgery depend on optimal postoperative care. Balanced fluid resuscitation, adequate inotropic support, attention to rewarming, preventive measures for deep venous thrombosis and bedsores, and ventilator management are vital components.[15]

Patients undergoing cardiac surgery suffer from adverse pathophysiological and psychological consequences of cardiac events, making them the prime candidates for cardiac rehabilitation. An individualized program formulation for an appropriate medical, rehabilitative, and surgical strategy to prevent the recurrence of cardiac events is the primary goal of such a program. It should curtail the pathophysiological and psychological effects of heart disease. It should limit the risk of reinfarction or sudden death. It should aim at relieving cardiac symptoms and reverse atherosclerosis by instituting programs for exercise training, education, counseling, and risk factor alteration. It should reintegrate heart disease patients into successful functional status in their families and society.

Consultations

The management of the ventricular aneurysm encircles around consultations from various specialties. The interprofessional team of healthcare providers consists of a primary care provider, cardiologist, interventional cardiologist, cardiac surgeon, interventional radiologist, pulmonologist, intensivist, anesthesiologist, etc.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Life after myocardial infarction can be a challenge for the patients. The patients face challenges in keeping compliance with new medications, access, and adherence to medication and medication-related adverse effects that may impact patients socially and financially. As myocardial infarction is the leading cause of ventricular aneurysms, a post-MI treatment plan including patient education, communication, and exercise intends to improve patient outcomes, hospital admissions, complications, and myocardial recurrence infarction.

A commitment to cardiac rehabilitation consists of compliance to medication regimens, managing comorbidities, modifying lifestyle, including diet and weight-loss strategies, if required, and routine follow-up with primary health providers can improve patient outcomes and quality of life. All these culminate in helping the patients in preventing post-MI complications, namely ventricular aneurysms.

Pearls and Other Issues

The incidence of LV free wall rupture in autopsy studies of patients with sudden death after an acute myocardial infarction is approximately 5%. A one-third of the pseudoaneurysms are located inferiorly. If free wall rupture occurs, but hemorrhage is contained by pericardial adhesions of peri-infarction pericarditis, the patient may survive, and left ventricular pseudoaneurysm is formed. The outer wall of the left ventricular pseudoaneurysm has no myocardial tissue and is avascular. Communication with the left ventricle is relatively narrow. The chest x-ray may show a pericardial mass with a characteristic notch at the border of the mass. Ventriculography will show the pseudoaneurysm unless a thrombus fills the cavity of the left ventricular aneurysm. Two-dimensional echocardiography will reveal a bulge in the left ventricle free wall characterized by a narrow neck and the presence of a clot in most cases. A characteristic finding is an abrupt discontinuity of the endocardial image between the pseudoaneurysm and the adjacent normal myocardium. The presence of a localized pericardial effusion should also suggest the diagnosis. Because of its tendency to rupture, a left ventricular pseudoaneurysm must be excised irrespective of symptomatology.[16]

Risk factors for hospital mortality include increased age, incomplete revascularization, increased heart failure class, female gender, emergent operation, an ejection fraction of less than 20% to 30%, concurrent mitral valve replacement, preoperative cardiac index of less than 2.1 L/m^2 per minute, mean pulmonary artery pressure greater than 33 mm Hg, serum creatinine concentration greater than 1.8 mg/dL, and failure to use the internal mammary artery.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional care team is an established entity in cardiovascular medicine. It improves the clinical outcomes while adhering to the evidence-based practice guidelines. As many as nine specialties can be in contact with one single patient, identifying and caring for their individual needs. Improvement in communication between different healthcare disciplines helps reduce the length of stay of patients and also impacts morbidity and mortality. Through leadership commitment from the cardiologist and cardiac surgeon, a programmatic approach can improve the delivery of quality evidence-based care in managing the ventricular aneurysm. To treat cardiovascular diseases, a new concept of a heart team is set into motion and has become the subject of increasing interest. Implementing a heart team can help put various issues into perspective for patients and their families. This interprofessional team includes an experienced cardiac surgeon, interventional cardiologist, and primary cardiologist, who work together to help focus on specific patient considerations and expectations.[16]

- A cardiologist has an essential role in managing the patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction and subsequent follow-up to monitor for post-infarction complications.

- An interventional cardiologist is involved in the decision-making process for disease management that encompasses revascularization therapies for patients with ischemic heart disease.

- The cardiac surgeon's role in the heart team involves deciding the optimal timing of the surgery.

- An anesthetist holds an integral position in the team to evaluate anesthetic risks in the perioperative management of the patient.

- An interventional radiologist helps in the diagnosis of the ventricular aneurysm by carrying out various imaging modalities.

- An intensivist after the cardiac surgery is an expert in the management of noncardiac complications as well as management of severe cardiac cases requiring a combination of mechanical ventilator support, antimicrobial regimens, hemodynamic tailoring, and renal replacement therapies.

- A clinical pharmacist offer suggestions for individual patient care through prospective or retrospective review based on pharmacological principles and provide medication education for patients and health care providers at all levels.

- A cardiac nurse plays a pivotal role in monitoring the patients as first-care responders and providing immediate care with the clinician's guidance.

- A physiotherapist is the profession of choice to lead cardiac rehabilitation programs.

- Pharmacists can be invaluable resources in anticoagulation management and dosing.

This interprofessional team approach will drive better outcomes for patients with LV aneurysms. [Level 5]