Introduction

The tympanic membrane (eardrum, myringa) is a thin, semitransparent, oval membrane, approximately 1 cm in diameter, that separates the external acoustic meatus from the tympanic cavity.[1][2] It is positioned at the lateral end of the external acoustic meatus and it is tilted medially from posteriorly to anteriorly and superiorly to inferiorly. Therefore, the lateral surface of the tympanic membrane faces anteriorly and inferiorly.

Structure and Function

The tympanic membrane consists of three layers, a thin sheet of connective tissue covered by epithelium on both sides. Its lateral (outer) surface is covered by a thin epidermis, i.e., stratified squamous keratinized epithelium, that is continuous with the epidermis of the external acoustic meatus. The medial (inner) surface is covered by a simple cuboidal epithelium that is continuous with the epithelium of the mucous membrane of the tympanic cavity.[3] The middle fibrous layer (lamina propria) is made up of fibroelastic connective tissue and contains the blood vessels and nerves of the tympanic membrane.[4] However, unlike most connective tissue, only a small amount of fibrils are made up of type I collagen, and instead, most are made of type II and type III collagen.[5]

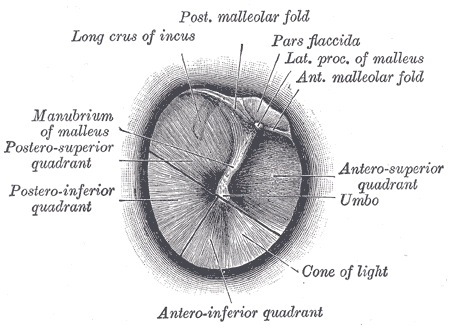

The fibrous layer is thickened at the edge of the inferior part of the tympanic membrane, forming a tough ligamentous ring, with which the tympanic membrane is lodged into the tympanic sulcus on the temporal bone. The manubrium of the malleus is attached to the medial surface of the tympanic membrane, and it pulls its anterior and inferior portion medially, giving it a conical shape. The central point of maximum depression is called the umbo, and it marks the end of the manubrium. When observing the lateral surface of the tympanic membrane, superiorly and anteriorly from the umbo, a line, the malleolar stria that corresponds to the manubrium of the malleus can be seen. Directly above the stria, the lateral process of the malleus bulges and forms the malleolar prominence. The part of the tympanic membrane above the malleolar prominence is not taut as it bridges the tympanic sulcus and is therefore called the pars flaccida (also called Shrapnell's membrane). The rest of the tympanic membrane, below the prominence, is taut and is called the pars tensa.[6] On the medial surface of the tympanic membrane, the border between the pars flaccida and tensa is marked by the anterior and posterior malleolar folds, whose purpose is to hold the lateral process in place. These ligamentous bands also contain the chorda tympani as it passes behind the tympanic membrane. Anatomically, the tympanic membrane can be separated into four quadrants using an imaginary line drawn vertically along the manubrium of the malleus and a line passing through the umbo and perpendicular to the first line. The quadrants are named: anterosuperior, anteroinferior, posteroinferior, and posterosuperior.

There are also microstructural differences in the lamina propria of the pars tensa and flaccida. While the pars tensa has organized radial and circular fibers, the pars flaccida instead has loosely arranged elastic collagen.[4] On the other hand, the pars flaccida is well vascularized, but the pars tensa lacks blood vessels in its semitransparent major portion.[7] Also, unlike the pars tensa, the pars flaccida contains numerous mast cells. Finally, contrary to popular belief, the pars flaccida is thicker than the pars tensa while being more elastic.[5]

The tympanic membrane has a rather simple function, sound transmission, and amplification. Similar to the membrane on a drum, the tympanic membrane vibrates as it encounters sound. It then transmits these vibrations to the ossicles of the middle ear to be further passed on to the cochlea of the inner ear for transduction.

Embryology

The tympanic membrane is derived from the invagination and meeting of the first pharyngeal groove (cleft) with the first pharyngeal pouch, and as such, it is comprised of two germ layers (ectoderm and endoderm). The lateral (external) epithelium is ectodermal in origin and is formed from the canalization of an ectodermal plug involved in the formation of the external acoustic meatus in the first pharyngeal groove. The medial aspect of the tympanic membrane is a continuation of the lining of the middle ear, which is endodermal in origin from the first pharyngeal pouch. The fibrous middle layer is derived from mesenchyme of neural crest origin and encases both the handle of the malleus and chorda tympani of the same origin. The chorda tympani is the pre-trematic nerve (coursing in the caudal aspect) of the first pharyngeal arch.[4] A common misconception is that the fibrous middle layer is derived from mesoderm, which would mean that the tympanic membrane is comprised of all three germ layers. However, since it is derived from neural crest mesenchyme, it is actually ectodermal in origin.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The lateral surface of the tympanic membrane is supplied by the deep auricular branch of the maxillary artery. The medial surface is irrigated by the anterior tympanic artery, a branch of the maxillary artery, and the posterior tympanic artery, a branch of the posterior auricular artery.[8] The lateral side of the tympanic membrane is drained into the external jugular vein, while the medial side is drained into the transverse venous sinus, which ultimately drains into the internal jugular vein.

Nerves

The lateral surface of the tympanic membrane receives sensory innervation from the auriculotemporal branch of the mandibular nerve, a branch of the trigeminal nerve (V3), the auricular branch of the facial nerve (CN VII), the auricular branch of the vagus nerve (CN X), and the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX). The medial surface of the tympanic membrane receives sensory innervation from the tympanic branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX).[9]

Muscles

There are no direct muscle attachments to the tympanic membrane. However, the tensor tympani muscle can pull the malleus inward to increase the tension across the tympanic membrane, effectively stiffening it. This involuntary activity is part of the acoustic reflex, which protects the tympanic membrane and the cochlear apparatus from acoustic, vibrational trauma precipitated by very loud sounds, including the sounds of chewing and talking. The stapedius muscle completes this reflex by retracting the stapes from the oval window to avoid damaging the cochlea with high-amplitude vibrations. The acoustic reflex requires approximately 40 milliseconds to take effect. Thus it is ineffective against very sudden loud sounds, for example, a gunshot.[10][11]

Surgical Considerations

Otoscopic Examination

The tympanic membrane can be visualized during an otoscopic examination. Considering that the external acoustic meatus is curved anteriorly and inferiorly, the external ear is gently pulled back and up to straighten the meatus and allow a clear view of the tympanic membrane. When performing an otoscopic examination on an infant, the external ear is pulled back and down due to the bony portion of the meatus not being fully developed. When light is directed at the tympanic membrane, a characteristic feature to be observed is the anterior cone of light, which radiates anteroinferior from the umbo. The tympanic membrane should be pearly-grey in color, translucent, shiny, and mobile on insufflation. If any of the aforementioned features of the tympanic membrane is altered, a pathological process, usually in the tympanic cavity, should be considered.

Myringotomy

Sometimes (e.g., recurrent otitis media infections), an incision in the tympanic membrane needs to be made, usually to allow drainage of fluid from the middle ear, and this procedure is called myringotomy (tympanostomy). The incision is made either in the posteroinferior (more often) or anteroinferior quadrant. The reason why inferior quadrants are incised instead of superior ones is that no important structures (e.g., chorda tympani) pass behind inferior quadrants, and they are generally devoid of blood vessels.

Clinical Significance

Rupture of the tympanic membrane may be caused by head trauma, loud blasts of sound, direct membrane trauma, barotrauma, and infection. The acoustic reflex provides some protection from loud sounds. Q-tips should only be used to clean the external ear and not be inserted into the external auditory canal. Fliers and divers may avoid barotrauma by equalizing the pressure across the tympanic membrane. Equalization is done by allowing air entry into the Eustachian tube, which connects the middle ear to the nasopharynx; techniques include performing a Valsalva maneuver with pinched nostrils, yawning, and swallowing. In the case of tympanic membrane rupture, patients may complain of pain and bloody effusion from the external auditory canal and may experience some conductive hearing loss and tinnitus. If no infection persists, the damaged tympanic membrane heals on its own. Patients should be advised to minimize water entry into the ear while the membrane is perforated to avoid injury to middle ear structures. Interestingly, intentional rupture of the tympanic membrane has been found to have been a typical practice among aquatic hunters of the Bajau people in the Southeast Asian Pacific. This would have been done to allow diving to great depths as part of their hunts. As a result, many of these hunters experience hearing impairment.[1]

Otitis media is a middle ear infection, which can cause an accumulation of pus behind the tympanic membrane. This may lead to pain or discomfort. Otoscopic examination typically reveals an erythematous and bulging tympanic membrane with obscured surface landmarks from distortion, possibly with a fluid layer or pus behind it. Recurrent otitis media infections may warrant tympanostomy tube placement to facilitate the drainage of pus and equalize the pressure across the tympanic membrane. The tympanostomy tubes are left in place for several months and are either removed later or fall out on their own.[12]

Cholesteatoma is keratinization of squamous epithelium, often associated with the pars flaccida in the posterior and superior portion of the tympanic membrane. It is a destructive lesion that tends to expand, and it can engulf the ossicles and even erode the skull. Cholesteatoma must be fully excised to prevent further growth. Deafness, vertigo, abscess, and septicemia may result if left untreated.[13]