Continuing Education Activity

Tibial shaft fractures are the most common long bone fractures and are seen in 4 percent of the senior population. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of tibial fractures and highlights the role of interprofessional team members in collaborating to provide well-coordinated care and enhance patient outcomes.

Objectives:

- Explain how a patient with a tibial fracture typically presents.

- Explain the evaluation of a patient with a probable tibial fracture.

- Contrast the management strategies for tibial fractures.

- Explore modalities to improve care coordination among interprofessional team members in order to improve outcomes for patients affected by tibial fractures.

Introduction

The proximal tibia is triangular in shape with a vast metaphyseal region narrowing distally. The tibia shaft is a long bone that articulates with the talus, fibula and the distal femur. The vascular anatomy is extensive and dependent on the compartment of muscles it supplies. The anterior tibial artery is the first branch of the popliteal artery, passes between the 2 heads of the tibialis anterior and Extensor hallucis longus (EHL) terminating as the dorsalis pedis. The posterior tibial artery is a continuation of the popliteal artery coursing in the deep compartment of the leg terminating as the medial and lateral plantar arteries. The peroneal artery terminates as the calcaneal arteries. It is important to understand the nerves and the compartments these nerves supply. The tibial nerve passes deep to the soleus, traveling down to the posterior aspect of the medial malleolus. The muscular branches of this nerve innervate muscles in the superficial and deep posterior compartments. The common peroneal nerve divides into the superficial and deep peroneal nerves. The superficial peroneal nerve is seen along the border between the lateral and anterior compartments and supplies the peroneus longus and brevis. The deep peroneal nerve, on the other hand, supplies the musculature of the anterior compartment and is sensory to the first web space. The saphenous nerve innervates the medial aspect of the foot and leg. The muscles of the deep compartment include popliteus, tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, and flexor hallucis longus. The muscles of the superficial posterior compartment include the gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantaris. Lateral compartment is composed of the peroneus longus and brevis. The anterior compartment is composed of the tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, extensor hallucis longus, and peroneus tertius.

Etiology

These fractures occur in a bimodal pattern involving both low-energy and high-energy mechanisms. With a low-energy injury, these are a result of a torsional force, indirect trauma resulting in spiral fractures, and/or a fibular fracture at a different level with a minimal soft-tissue injury.[1][2]High-energy mechanism injury is usually a result of direct trauma causing wedge or short oblique fractures and significant comminution and can be associated with soft-tissue injury, compartment syndrome, bone loss, and ipsilateral-skeletal injury.

Epidemiology

In general, the tibial shaft fractures are the most common long bone fractures and seen in 4% of the senior population.

History and Physical

Patient presentation and physical exam are the same for most tibia fractures. Patients with this injury present with the inability to bear weight and deformity. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for elevated compartment pressures, especially in the higher impact trauma patient.

Evaluation

Evaluating the range of motion and stability are often difficult due to pain.[3][4][5]

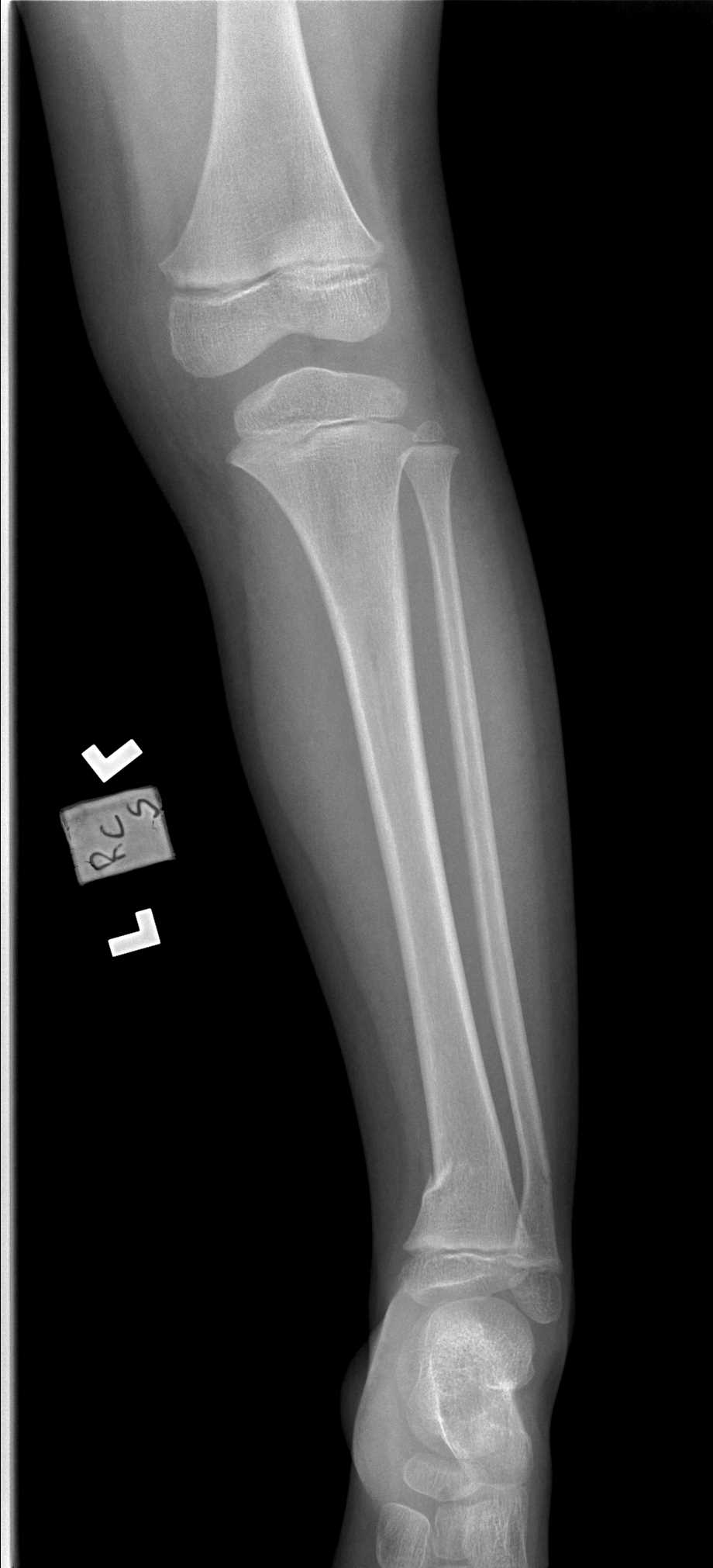

The neurovascular exam is very important to assess the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibialis arteries. The soft tissues must be assessed to identify any signs or symptoms of compartment syndrome. The skin should be evaluated for lesions, abrasions, fractures blisters and the condition of the compartments. To appropriately diagnose compartment syndrome, a high threshold of suspicion is necessary. Recommended imaging includes full-length AP and lateral views of the affected area, AP, lateral and oblique views of the ipsilateral knee and ankle. CT scan is indicated to identify an intra-articular involvement and exclude posterior malleolar fracture in spiral distal third fractures.[6][7][8]

Classifications

Some classifications help with treatment decisions.

Oestern and Tscherne

This is a classification of closed fracture soft tissue injury and is as follows:

- Grade 0: Injuries from indirect forces with minimal soft tissue damage

- Grade 1: Superficial contusion/ abrasion, simple fractures

- Grade II: Deep abrasions, muscle/skin contusion, direct trauma, impending compartment syndrome

- Grade III: Excessive skin contusion, crushed skin or muscle destruction, subcutaneous degloving, acute compartment syndrome, and rupture of a major blood vessel or nerve

The Gustilo-Anderson

This classification is used to assess open tibia fractures.

- Type I is limited periosteal stripping, clean wound less than 1 cm

- Type II mild to moderate periosteal stripping; wound greater than 1 cm in length

- Type IIIA significant soft tissue injury, significant periosteal stripping with a wound that is usually greater than 1 cm in length with no flap required

- Type IIIB is significant periosteal stripping and soft tissue injury with a flap required due to inadequate soft tissue coverage

- Type IIIC these are significant soft tissue injury with a vascular injury requiring repair

Treatment / Management

Non-Operative Treatment

Closed-reduction and nonoperative treatment in a long leg cast is acceptable for fractures in less than 5 degrees of varus-valgus angulation, less than 10 degrees in anterior-posterior angulation, greater than 50% cortical apposition, less than 1-cm shortening and less than 10 to 20 degrees of flexion and less than 10 degrees of rotational malalignment after reduction.

Operative Treatment[2][9][10]

External Fixation

Treatment of choice when significant soft tissue compromise is present or in polytrauma cases where damage-control orthopedics is needed.

Intramedullary Nailing (IMN)

This is the treatment of choice for operative fixation.

When comparing outcomes of IMN with external fixation, IMN is associated with decreased malalignment and compared to closed treatment, IMN is associated with decreased union time and time to weight bearing.

Percutaneous Plating-Shaft

This method is often used in the distal tibia or proximal-third fractures that are too proximal or distal for intramedullary nailing.

Amputation

This is another treatment method but can be difficult to get the patient to buy into this treatment. The mangled extremity severity score (MESS) can help predict when an amputation is necessary. A score of 7 or greater is highly predictive of amputation. MESS has a high specificity but low sensitivity in predicting amputations. Relative indications include significant soft tissue trauma, warm ischemia greater than 6 hours, and severe ipsilateral foot trauma. It is important to note that loss of plantar sensation is not an absolute indication for amputation.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis before radiographs should include stress fractures in active individuals as well as bone contusion.

Prognosis

Fracture of the proximal third of the shaft has a higher rate of nonunion compared to midshaft fractures. This is in combination due to the deforming forces in the proximal aspect of the tibia as well as limited soft tissue coverage. However, if managed and fixed appropriately, outcomes are typically good. Nonoperative management of tibia fracture has a high success rate if the alignment is maintained. The risks of this type of treatment increase with oblique fracture patterns. The most important predictor of eventual amputation is the severity of the ipsilateral extremity soft tissue injury. It has been shown that there is no significant difference in functional outcomes between amputation and salvage.

Complications

The complications of percutaneous plating include increased rates of nonunion and delayed union, wound dehiscence and long plates may irritate the superficial peroneal nerve proximally or distally. Malunion in valgus and procurvatum is seen most commonly in proximal-third fractures. Nonunion is an uncommon complication with intramedullary nail fixation but is treated by dynamization of the nail. Malrotation is most commonly seen in proximal and distal-third fractures. Knee pain is the most common complication after intramedullary nailing which occurs during the patellar tendon splitting and paratenon approach. Compartment syndrome is another complication which can be seen in both open and closed fractures.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

For tibial shaft fractures that are treated non-operatively, the patient should remain non-weight bearing for 6 weeks while in a long leg case. Patients treated in an external fixation, especially for length unstable fractures should remain non-weight bearing for 6 weeks for extra-articular fractures and up to 12 weeks for intraarticular fractures. For length-stable fractures, some surgeons choose to allow patients to bear weight as tolerated when they have transverse tibial shaft fractures that are stable. For operative fixation, whether it be IMN or plating the same applies as for external fixation. Weight-bearing as tolerated length stable, extra-articular, transverse shaft fractures, and non-weight bearing for unstable, oblique, or comminuted fractures for 6 weeks in the extra-articular setting and 12 weeks when the joint surface is involved.

Maintaining active knee and ankle range of motion is important during the recovery period.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis should be administered to non-weight bearing, lower extremity fractures.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of tibial fractures requires an interprofessional team that includes an orthopedic surgeon, emergency department physician, radiologist, nurse, and a physical therapist. These fractures have very high morbidity and the nurse monitoring the patient should be aware of the risks of deep vein thrombosis and compartment syndrome. The leg has to be monitored for pulse, color, temperature and neuropathic changes to ensure that compartment syndrome is not developing. Even after treatment, most patients need a prolonged recovery period combined with physical therapy. The outcomes are good for simple tibial fractures but complex fractures can result in residual pain, prolonged wound healing and difficulty with gait.[11][12]