Continuing Education Activity

Thalassemias are a common cause of microcytic anemia and are due to impaired synthesis of the globin protein component of hemoglobin. Beta-thalassemia is an inherited disease with a wide phenotypic severity of the disease. Manifestations of the disease occur in the form of chronic anemia as well as significant pathology associated with bone marrow expansion and extramedullary hematopoiesis. This activity reviews the evaluation and management principles of beta-thalassemia and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of beta-thalassemia.

- Explain the evaluation of beta-thalassemia.

- Summarize the treatment options available for beta-thalassemia.

- Identify interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and outcomes in patients with beta-thalassemia.

Introduction

Thalassemias are a common cause of hypochromic microcytic anemia which arises from the reduced or absent synthesis of the globin chain of hemoglobin. Thalassemias are a quantitative defect of hemoglobin synthesis. This is in contrast with hemoglobinopathies, such as sickle cell disease, which are structural or qualitative defects of hemoglobin. Beta-thalassemia refers to an inherited mutation of the beta-globin gene, causing a reduced beta-globin chain of hemoglobin. The highest prevalence of beta-thalassemia mutations is in people of Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and Asian descent. Over 200 different thalassemia-causing mutations have been identified in the beta-globin gene, leading to the disease's wide genotypic and phenotypic variability.[1] The three classifications of beta-thalassemia are defined by their clinical and laboratory findings. Beta-thalassemia minor, also called carrier or trait, is the heterozygous state that is usually asymptomatic with mild anemia. Homozygosity or compound heterozygosity for beta-thalassemia mutations cause a more severe spectrum of anemias called beta-thalassemia intermedia and beta-thalassemia major. These two are distinguished clinically by transfusion dependence. Beta-thalassemia major requires routine transfusions, and intermedia does not.

Laboratory findings suggestive of thalassemia include microcytic hypochromic anemia. There may be significant anisopoikilocytosis (variation of size and shape) in cases of beta-thalassemia major on peripheral smear. Exclusion of iron deficiency and hemoglobin electrophoresis or high-performance liquid chromatography are often required for diagnosis. Treatment, if required, is primarily with blood transfusion, depending on the degree of anemia. Complications of beta-thalassemia include iron overload and bone-deforming marrow expansion with extramedullary hematopoiesis.

Etiology

Beta-thalassemia is an inherited disorder resulting from various mutations (over 200 disease-causing mutations have been identified) or, rarely, deletions of the beta-globin gene (HbB) on chromosome 11. These mutations are primarily point mutations that affect transcriptional control, translation, and splicing of the HbB gene and gene product.[1]

The spectrum of disease severity is due to the bi-allelic inheritance of two copies of the beta-globin gene, one on each chromosome 11, as well as the heterogeneous pool of disease-causing mutations. The genotypic variability of beta-globin synthesis is designated beta(+) for decreased production and beta(0) for absent production. The phenotypic variability is designated as either minor, intermedia, or major. Beta-thalassemia minor is heterozygosity with one unaffected beta-globin gene and one affected, either beta(+) or beta(0). Homozygosity or compound heterozygosity with beta(+) or beta(0) causes intermedia and major. These two are distinguished clinically by the severity of anemia and not by genotype.

Epidemiology

The frequency of beta-thalassemia mutations varies by regions of the world with the highest prevalence in the Mediterranean, the Middle-East, and Southeast and Central Asia. Approximately 68000 children are born with beta-thalassemia. Its prevalence is 80-90 million carriers, around 1.5% of the global population.[2] The reported carrier prevalence in Greek and Turkish populations in Cyprus is up to 15%.[3] The prevalence also parallels that of malaria as a proposed survival advantage provides the selective pressure for the high carrier frequency in these populations. Gene drift and founder effects are other reasons why thalassemia is more frequent in the areas mentioned above.[4]

Pathophysiology

Hemoglobin is a tetramer of two alpha globin chains combined with two non-alpha globin chains. Fetal hemoglobin (HbF) is the primary hemoglobin until six months of age and consists of two alpha chains and two gamma chains. Adult hemoglobin is primarily hemoglobin A (HbA), consisting of two alpha chains and two beta chains. A smaller component of adult hemoglobin is hemoglobin A2 (HbA2), consisting of two alpha chains and two delta chains.

The pathogenesis of beta-thalassemia is two-fold. First, there is decreased hemoglobin synthesis causing anemia and an increase in HbF and HbA2 as there are decreased beta chains for HbA formation. Second, and of most pathologic significance in beta-thalassemia major and intermedia, the relative excess alpha chains form insoluble alpha chain inclusions that cause marked intramedullary hemolysis. This ineffective erythropoiesis leads to severe anemia and erythroid hyperplasia with bone marrow expansion and extramedullary hematopoiesis. The bone marrow expansion leads to bony deformities, characteristically of the facial bones which cause frontal bossing and maxillary protrusion. Biochemical signaling from marrow expansion involving the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathway inhibits hepcidin production causing iron hyperabsorption.[5] Inadequately treated patients and transfusion-dependent patients are at risk for end-organ damaging iron overload. Hepatosplenomegaly from extramedullary hematopoiesis and ongoing hemolysis also causes thrombocytopenia and hepatic dysfunction.

Beta-thalassemia minor causes microcytosis with, at most, mild anemia as a result of reduced HbA synthesis. Individuals with beta-thalassemia minor have one unaffected beta-globin gene, so they can still produce sufficient hemoglobin to supply the body’s regular demand without causing significant erythroid hyperplasia. Furthermore, the hemoglobin deficit is compensated by an increase in other hemoglobin forms, commonly HbA2.

Beta-thalassemia can also coexist with other hemoglobinopathies (hemoglobin S, C, and E, for example) and cause variably clinically significant anemias in the heterozygous beta-thalassemia carrier. Delta-beta-thalassemia is clinically similar to beta-thalassemia, and it occurs when there is a deletion of the neighboring delta and beta genes. The pathophysiology of delta-beta-thalassemia parallels that of beta-thalassemia, except there is not an increased HbA2 since the delta chain is also affected.

History and Physical

Beta-thalassemia minor is typically discovered incidentally on routine complete blood count. Patients may have mild symptoms of anemia without significant physical exam findings.

Patients with beta-thalassemia major (TM), if the diagnosis has not been determined prenatally, present between 6 and 24 months of age when hemoglobin production transitions from fetal (HbF) to adult (HbA). Severe anemia ensues and presents as feeding problems, irritability, failure to thrive, pallor, diarrhea, irritability, recurrent bouts of fever, and abdominal enlargement from hepatosplenomegaly. Untreated or undertreated infants, especially in resource-poor areas, will suffer from growth retardation, jaundice, brown pigmentation of the skin, poor musculature, genu valgum, hepatosplenomegaly, leg ulcers, development of masses from extramedullary hematopoietic sites, and skeletal deformities from bone marrow expansion. Frontal bossing, maxillary hypertrophy, and long bone deformities are common skeletal findings.[2]

Beta-thalassemia intermedia encompasses a wide range of clinical presentations, although, by definition, it is not severe enough to require regular transfusions. Intermedia can present in children as young as two years of age with growth and developmental delay. Milder forms of beta-thalassemia intermedia may first present in adults as fatigue and pallor. Beta-thalassemia intermedia can have variable degrees of physical exam findings suggestive of erythroid hyperplasia and extramedullary hematopoiesis as described for the beta-thalassemia major; however, this reactive hematopoiesis is sufficient to compensate for the anemia without requiring transfusion.[6] With longstanding hemolysis, patients with beta-thalassemia major and intermedia can have signs and symptoms of gallbladder disease secondary to gallstone formation.[7][8]

Evaluation

Clinical diagnosis of beta-thalassemia major (TM) is made in children less than 2 years of age that present with microcytic anemia, mild jaundice, and hepatosplenomegaly.

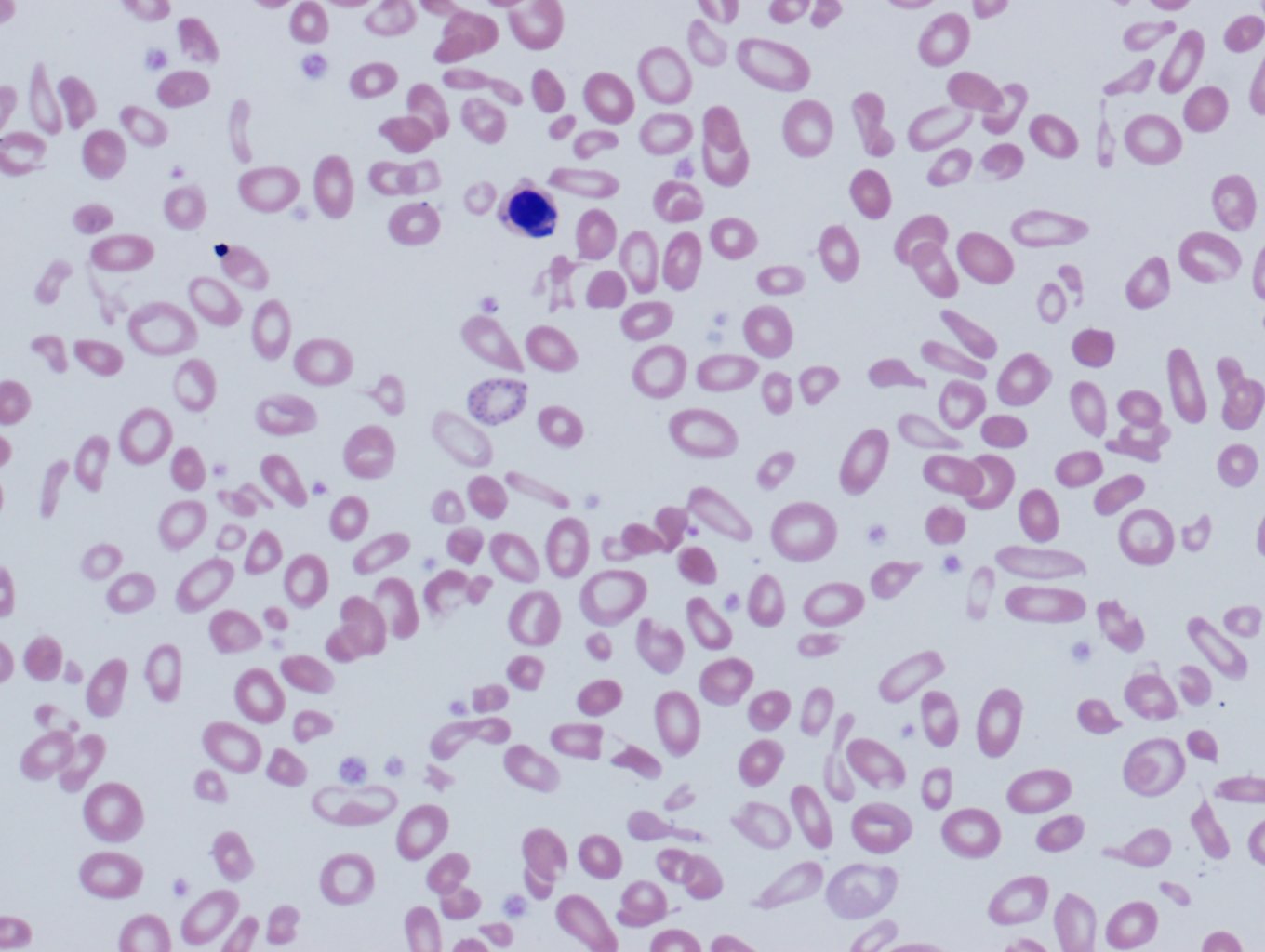

The complete blood count (CBC) of a patient with beta-thalassemia major will show microcytic hypochromic anemia with Hb levels less than 7g/dl, the mean corpuscular volume between (MCV) 50 and 70 fl, and mean corpuscular Hb (MCH) between 12 and 20pg. Beta- thalassemia intermedia presents with values of Hb between 7 and 10 g/dl, MCV 50 to 80 fl, and MCH 16 to 24pg. In beta-thalassemia minor, the red cell number is often elevated, reduced MCV, MCH, and the red cell distribution width (RDW) will typically show low elevations. The normal to mildly elevated RDW can help differentiate thalassemias from other microcytic hypochromic anemias, such as iron deficiency anemia and sideroblastic anemia where the RDW is typically very high. The peripheral blood smear will show microcytic hypochromic anemia with target cells, teardrop cells, and often coarse basophilic stippling (see Image 1). In severe forms of beta-thalassemia, there is anisopoikilocytosis with bizarre red cell morphology and numerous nucleated red blood cells.[2]

The CBC and peripheral smear findings are non-specific. A diagnosis of beta-thalassemia requires hemoglobin electrophoresis or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to demonstrate abnormal percentages of HbA, HbA2, and sometimes HbF. The general pattern of beta-thalassemia is a decreased HbA percentage and a mildly increased HbA2; less than 10% with variably increased HbF. A HbA2 above 10% suggests variant hemoglobin rather than beta-thalassemia. The magnitude of the HbA decrease depends on the genetic makeup of the affected individual. Patients with beta(+) alleles will have variably decreased HbA levels, and those that are homozygous beta(0) will produce no HbA. Beta-thalassemia minor characteristically has increased HbA2 (4-8%) with variably normal-to-low elevations of HbF. Beta-thalassemia major typically shows markedly elevated HbF (30-to-greater than 95%) with normal to mildly elevated HbA2. The distinction between beta-thalassemia major and intermedia is a clinical one and does not have diagnostic laboratory findings.

A common confounding factor in hemoglobin electrophoresis is a concomitant iron deficiency that masks an underlying beta-thalassemia minor. The resultant electrophoresis pattern appears normal. This is because iron deficiency anemia normalizes the HbA2 percentage that is the key finding in beta-thalassemia minor. Other causes of elevated HbA2 other than thalassemia include antiretroviral therapy, vitamin B12/folate deficiency, and hyperthyroidism. Hemoglobin electrophoresis and high-performance liquid chromatography can also elucidate other hemoglobinopathies complicating a beta-thalassemia trait.

Treatment / Management

As thalassemia minor is a carrier state, it is typically asymptomatic. Genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis might be indicated when carriers are detected. Thalassemia major is treated with red blood cell transfusion. The aim of transfusion is mainly to suppress erythroid expansion. It also serves to mitigate symptoms of anemia and to inhibit gastrointestinal iron absorption. Severe anemia and growth delays are indications for transfusions as well as clinical signs of erythroid expansion, including facial changes, bony expansion, and splenomegaly. The goal hemoglobin level for most transfusion regimens is pretransfusion hemoglobin of 9 to 10 g/dL and posttransfusion hemoglobin of 13 to 14 g/dL.[9] Regular transfusions put patients at risk of iron overload, transfusion reactions, and also developing red cell antibodies, which makes finding suitable donor blood for subsequent transfusions difficult. Bone marrow transplant and cord blood transplant offer the only potential cure for beta-thalassemia.[10] In patients without pre-transplant complications of clinical progression of the disease, stem cell transplantation of HLA-identical siblings has a disease-free survival rate of over 90%. Cord blood transplant is a consideration for parents who already have a child with beta-thalassemia and later identify an HLA-compatible fetus in a subsequent pregnancy.[11]

The iron status of routinely transfused patients must be monitored. Clinical signs of iron overload and serial serum ferritin remain the most reliable method to evaluate iron overload. Iron chelation therapy is generally started after patients have received 10 to 20 transfusions or have serum ferritin levels more than 1000 ng/mL. Other nutritional sequelae of thalassemia include relative folate deficiency, calcium depletion, and vitamin C deficiency.[7] Symptomatic hypersplenism is common in thalassemia intermedia and major and may be treated with splenectomy. Post-splenectomy patients have an increased susceptibility to blood-borne infections with encapsulated bacteria and should receive appropriate immunizations.

Follow up

In patients with beta-thalassemia major (TM), follow-up is mandatory to monitor transfusion therapy response and chelation therapy side effects. It is recommended a physical exam is performed every month, an assessment of liver function tests every two months, serum ferritin every three months, growth and development every six months in pediatric patients, ophthalmologic, and audiology examinations. In patients 10 years of age and older, a complete cardiac evaluation, thyroid, parathyroid, endocrine pancreas, adrenal and pituitary function evaluations, liver ultrasound, serum alpha-fetoprotein for early detection of hepatocarcinoma, and bone densitometry for osteoporosis are recommended to be performed annually.[1] MRI of the liver and heart to detect iron overload and repeated according to the severity of iron overload. In patients with Gilbert syndrome genotype, regular gallbladder echography for early detection of cholelithiasis is recommended.[12][13]

Differential Diagnosis

The major differential diagnosis in hypochromic microcytic anemia are:

- Alpha thalassemia

- Anemia of chronic disease

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Sideroblastic anemia

- Lead nephropathy

Beta-thalassemia can be differentiated from sideroblastic anemias because thalassemias lack ring sideroblasts in the bone marrow and lack elevation of erythrocyte protoporphyrin. Iron deficiency is easily ruled out with reference range iron studies (serum iron, total iron-binding capacity, percent transferrin saturation). Hemoglobinopathies typically require hemoglobin electrophoresis or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for diagnosis.

Prognosis

Prognosis before 2000 was poor. In the United Kingdom (UK), approximately 50% of beta-thalassemia major (TM) patients died before age 35 years.[14] Now since 2000, prognosis has changed dramatically; over 80% of patients live longer than 40 years in the UK. This is due to the apparition of noninvasive methods to measure organ iron before the appearance of clinical symptoms, new chelators, and increased blood safety measures.[15]

Complications

Complications are related to overstimulation of bone marrow, ineffective erythropoiesis, and iron overload from blood transfusions.

Iron accumulates in the heart, causing heart failure, which is the most common cause of death in beta-thalassemia major (TM) due to iron accumulation. The symptoms differ from nonanemic patients because of adaptation to chronic anemia. Usually, these patients have dyspnea, with resting tachycardia, low blood pressure, high ejection fraction, and high cardiac output.[16] Atrial fibrillation is another long-term complication of iron oxidative stress. According to several studies, it is more prevalent in TM patients than in the general population.[17]

Iron also accumulates in endocrine glands causing hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, and hypogonadism.[18]

Thromboembolic events such as deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and recurrent arterial occlusion are more common in thalassemia patients than in the normal population. This complication is due to a chronic hypercoagulable state, particularly in thalassemia intermedia. They have low levels of protein C and protein S, increased D-dimer levels.[19]

Other complications are chronic hepatitis (from blood transfusion infection of hepatitis B and C viruses), cirrhosis (iron overload), hypersplenism, HIV infection, and osteoporosis.[2]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Thalassemia minor patients must be educated about the hereditary nature of their disease and they must be informed that their parents, siblings, and children may be affected. If both parents have beta-thalassemia minor, there is a one-fourth chance that a child has thalassemia major. Careful genetic counseling is needed when one parent has thalassemia minor and the other parent has other beta globin-related diseases, such as sickle cell carriage. Patients with beta-thalassemia minor should be told that iron supplementation would not improve their anemia as they don't have iron deficiency anemia.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Clinically significant beta-thalassemia presents in childhood, making it a familiar diagnosis for all providers providing pediatric care. While the pediatrician or family practice provider may be the first to discover a hematologic abnormality, coordination with an interprofessional team comprising hematologists, pathologists, and nurses familiar with beta-thalassemia is necessary for optimal diagnosis and management. Care plans may include nutrition counseling and exercise consultation.[20][21] [Level 2]