Continuing Education Activity

Tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS) is sometimes referred to as "tibial nerve dysfunction" or "posterior tibial nerve neuralgia." This condition is an entrapment neuropathy associated with the compression of tarsal tunnel structures. TTS may be considered carpal tunnel syndrome's counterpart at the ankle, though this lower limb condition is much less common.

TTS can mimic more frequently encountered clinical entities like diabetic neuropathy and plantar fasciitis. Inaccurate diagnosis and inappropriate management can produce complications such as foot deformities and functional impairment.

This activity for healthcare workers is designed to enhance learners' competence in evaluating and managing TTS. This activity is also intended to equip learners to collaborate effectively with an interprofessional team caring for patients with TTS.

Objectives:

Differentiate tarsal tunnel syndrome from other lower limb conditions based on signs and symptoms.

Implement evidence-based individualized treatment plans for an individual with this tarsal tunnel syndrome.

Identify the potential complications of tarsal tunnel syndrome.

Develop interprofessional team strategies to improve care coordination for patients with tarsal tunnel syndrome.

Introduction

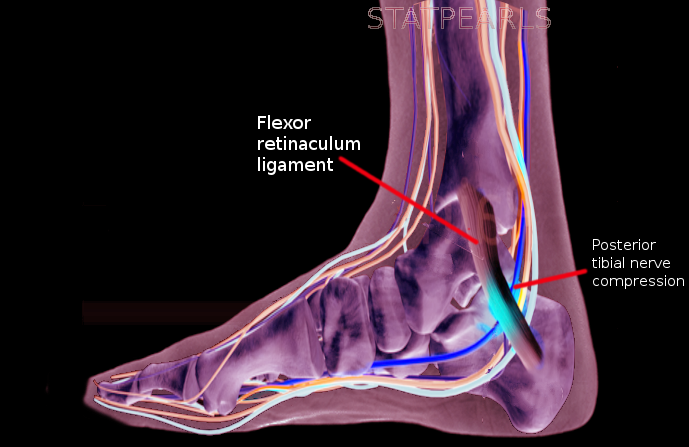

Tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS), sometimes referred to as "tibial nerve dysfunction" or "posterior tibial nerve neuralgia," is an entrapment neuropathy arising from the compression of the tarsal tunnel structures, particularly the posterior tibial nerve (see Image. Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome).[1] This condition is often compared to carpal tunnel syndrome in the wrist, as both involve nerve compression in a confined space. However, TTS is much less common than carpal tunnel syndrome.[2][3][4][5] The diagnosis is often clinical, though diagnostic tests may help identify a treatable source or rule out other serious conditions.

Anatomy of the Tarsal Tunnel

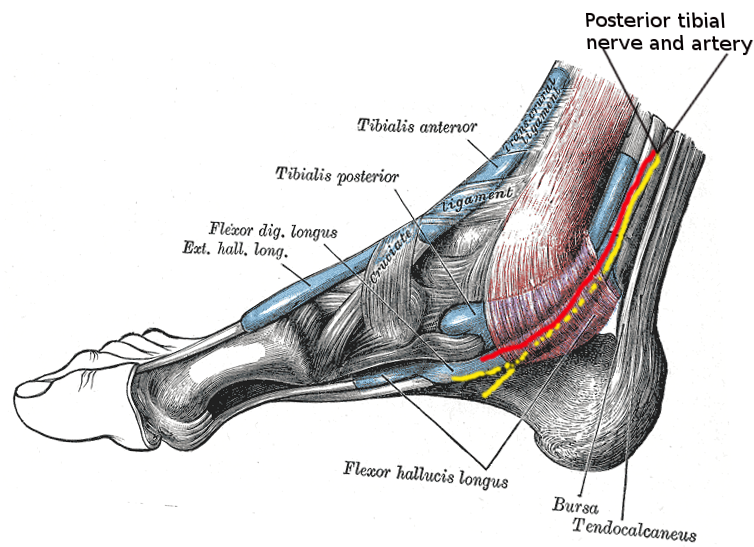

The tarsal tunnel is a narrow fibro-osseous space that runs posteroinferior to the medial malleolus (see Image. Tarsal Tunnel Anatomy). The tunnel's roof consists of the flexor retinaculum, passing from the medial malleolar tip to the medial calcaneal process and plantar aponeurosis. The floor comprises the medial surfaces of the tibia, talus, and calcaneus.

The tarsal tunnel houses multiple essential structures, including the following:

- Tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus (FDL), and flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendons

- Posterior tibial artery and vein

- Posterior tibial nerve (L4 to S3)

The orientation of these structures within the tarsal tunnel is noteworthy. The structures from medial to lateral are the tibialis posterior tendon, FDL tendon, posterior tibial artery and vein, posterior tibial nerve, and FHL tendon. Meanwhile, the structures from anterior to posterior are the tibialis posterior tendon, FDL tendon, posterior tibial neurovascular bundle (artery, vein, and nerve), and FHL tendon.

The posterior tibial nerve passes between the FDL and FHL muscles before it bifurcates in the tarsal tunnel, forming the medial and lateral plantar nerves. In 5% of people, the bifurcation occurs proximal to the tarsal tunnel.[6]

The medial plantar nerve passes deep to the abductor hallucis and FHL muscles. This nerve has the following functions:

- Provides afferents in the medial half of the foot

- Provides afferents in the first 3 foot digits

- Supplies efferents to the 1st lumbrical, abductor hallucis, flexor digitorum brevis, and flexor hallucis brevis

The lateral plantar nerve passes directly through the abductor hallucis muscle belly and has the following functions:

- Provides afferents in the medial calcaneus

- Supplies afferents in the lateral heel

- Provides efferents in the flexor digitorum brevis, quadratus plantae, and abductor digiti minimi

The medial calcaneal nerve typically branches off the posterior tibial nerve proximal to the tarsal tunnel and provides sensory innervation to the posteromedial heel. This nerve diverges from the lateral plantar nerve or runs superficial to the flexor retinaculum in 25% of patients.

Etiology

TTS causes may be intrinsic or extrinsic.[7][8] Intrinsic causes of this condition include abnormalities of the tarsal tunnel structures, such as tendinopathy, tenosynovitis, perineural fibrosis, osteophytes, hypertrophic retinaculum, and space-occupying lesions like varicose veins, ganglion cysts, lipomas, neoplasms, and neuromas. Meanwhile, extrinsic TTS causes include external or systemic conditions affecting the tarsal tunnel, such as poorly fitting shoes, trauma, anatomic-biomechanical abnormalities (eg, tarsal coalition, valgus or varus hindfoot), generalized lower extremity edema, systemic inflammatory arthropathies, diabetes, and postsurgical scarring.

The impingement mechanism can be identified in approximately 80% of cases. Idiopathic tarsal tunnel syndrome is rare. Arterial insufficiency can lead to nerve ischemia.

Epidemiology

The incidence of TTS is unknown. The condition is relatively rare and often underdiagnosed. What is known, however, is that TTS incidence is higher in females than males, and the condition can be seen at any age.

Pathophysiology

TTS results from the compression of the posterior tibial nerve or one of its 2 branches, the lateral or medial plantar nerve, within the tarsal tunnel. Up to 43% of patients have a history of trauma, including events like ankle sprains. Abnormal biomechanics can contribute to disease progression. Risk factors include systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, gout, mucopolysaccharidosis, and hyperlipidemia.

History and Physical

Patient Examination

The predominant patient complaint when obtaining history is pain directly over the tarsal tunnel radiating to the arch and plantar foot. The pain may radiate up to the calf or higher.[9] Patients with TTS frequently report sharp, shooting foot pain, plantar numbness, pain radiation and paresthesias along the posterior tibial nerve distribution, pain on extremes of dorsiflexion and eversion, and a tingling or burning sensation. These symptoms may localize to the medial ankle or plantar foot surface or be vaguer, making diagnosis difficult. Symptoms vary depending on whether the entire posterior tibial nerve or one of its branches is compressed. The symptoms may worsen at night, with walking or standing, or after physical activity and typically improve with rest. The patient may experience foot muscle weakness. Dysesthesias may worsen at night, disturbing sleep.

The provider may observe pes planus, pronated foot, or talipes equinovarus on physical examination. Atrophy, intrinsic foot muscle weakness, and toe contractures may be appreciated in chronic cases. TTS may affect gait, so clinicians must look for abnormalities such as excessive pronation or supination, toe eversion, excessive foot inversion or eversion, and antalgic gait. Tarsal tunnel tenderness may be elicited on deep palpation.

Light touch and 2-point discrimination should be tested. The patient may have diminished plantar sensation in the medial or lateral plantar nerve distribution. Muscle strength and foot range of motion should be assessed. Strength deficits are typically a late finding in TTS.

The Tinel test may be performed by repeatedly tapping over the tarsal tunnel. Pain or tingling in the posterior tibial distribution is a positive test and a strong predictor of surgical relief after decompression.[10] However, the sensitivity of this test is low at 25% to 75%. Meanwhile, the specificity of the Tinel test is 70% to 90%.

Another test that may be performed during the physical examination is the dorsiflexion-eversion test, which involves passively dorsiflexing and everting the ankle to the end of the range of motion and holding for 10 seconds. Reproduction of symptoms is due to posterior tibial nerve compression in this position and is a positive sign. This test is positive in 82% of patients with TTS.

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome Severity Rating Scale

The condition's severity may be assessed using the TTS severity rating scale below. A score of 10 is a normal finding, while 0 indicates that the condition's symptoms are severe.

- Scoring for each symptom:

- 2 points for the absence of features

- 1 point for some features

- 0 points for definite features

- The 5 symptoms:

- Spontaneous pain or pain with movement

- Burning pain

- Tinel sign

- Sensory disturbance

- Muscle atrophy or weakness [11]

However, this evaluation tool may not be adequate for patients with vague symptoms. Although TTS is a clinical diagnosis, further tests may be necessary if clinical assessment is inadequate to differentiate between serious foot disorders.

Evaluation

No specific test exists for detecting TTS, so the diagnosis is often made clinically. However, imaging and neurophysiological studies can help rule out other conditions or identify the cause of the symptoms.

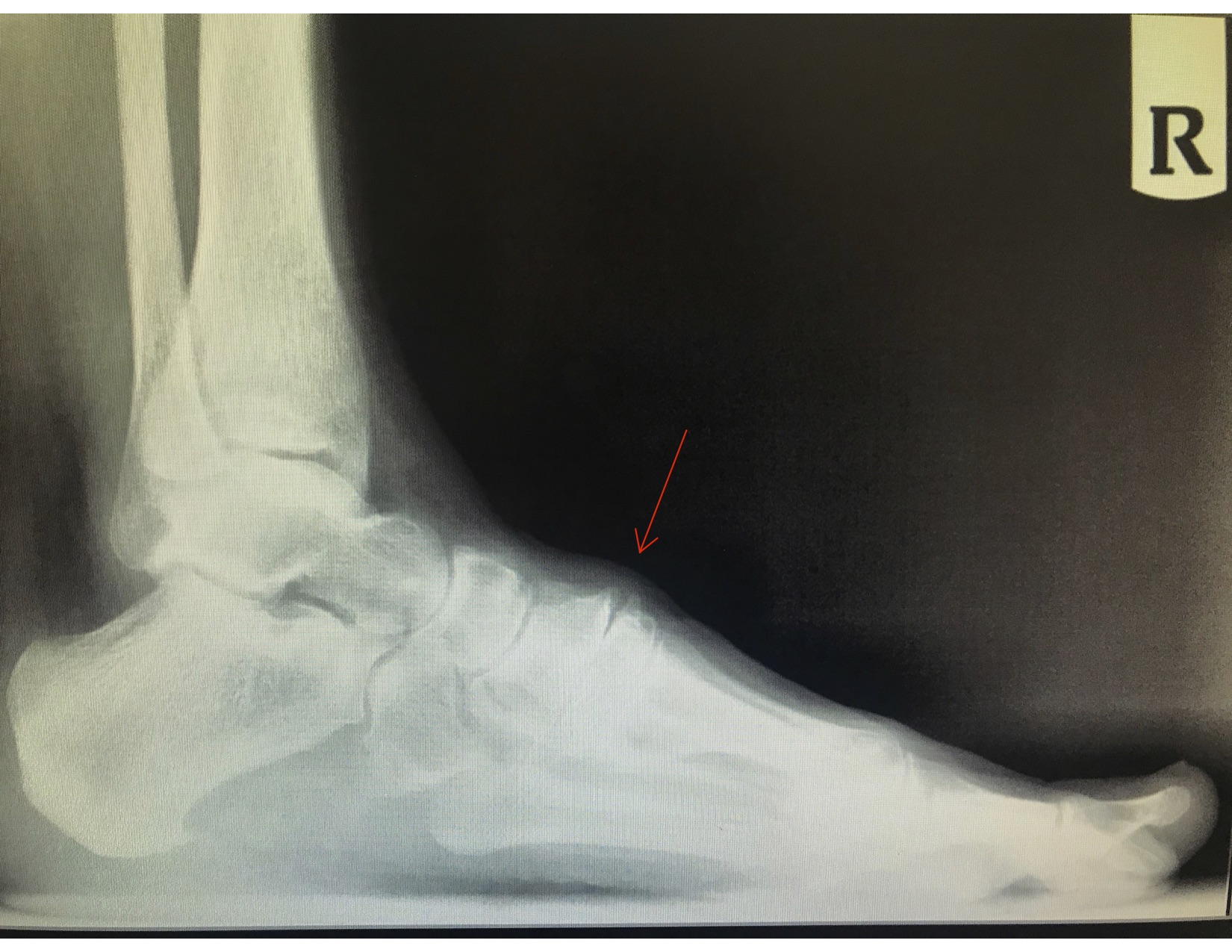

Plain ankle and foot radiography is the initial imaging study of choice (see Image. Anterior Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome from Osteophyte Formation). X-rays can help identify structural abnormalities, including osteophytes, hindfoot varus and valgus, tarsal coalition, and evidence of previous trauma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not sensitive for diagnosing TTS but may help include or exclude other causes of the patient's symptoms.

Ultrasound may be used to evaluate soft tissue structures. This modality allows visualization of the posterior tibial nerve and its bifurcations. Ultrasound and MRI can evaluate other soft tissue abnormalities, including tendonitis or tenosynovitis, lipomas or other growths, varicose veins, and ganglion cysts.[12]

Electromyography and nerve conduction studies are frequently abnormal in patients with TTS. Sensory nerve conduction studies are more likely to be abnormal than motor nerve conduction studies. However, the sensitivity and specificity of these tests are suboptimal. False-negative results are not uncommon and thus do not rule out the diagnosis.

Treatment / Management

TTS management remains challenging due to uncertainties in the diagnosis and in identifying patients who would benefit from the currently recommended interventions. Treatment may be conservative or surgical. Management choices are generally guided by the disease etiology, degree of foot and ankle function loss, and presence of muscle atrophy.[13][14]

The success of conservative management varies based on the etiology. The goal is to reduce pain, inflammation, and tissue stress. Ice may be used to treat inflammation and pain. Nonopioid analgesics, ie, acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), may also help. Neuropathic pain medications that may be prescribed on a trial basis include gabapentin, pregabalin, and tricyclic antidepressants. Topical lidocaine and NSAIDs have also been used for symptom relief. Corticosteroid injection may also be administered for pain relief and making the diagnosis.

Physical therapy soft tissue modalities that may help enhance foot and ankle function include ultrasound, iontophoresis, phonophoresis, and electrical stimulation. Tibialis posterior strengthening and kinesiology tape can help improve foot stability by supporting the arch and reducing biomechanical stress in the area. Activity modification, calf stretching, and nerve mobility or gliding can help alleviate the symptoms.

Orthotic shoes may be used to correct biomechanical abnormalities and offload the tarsal tunnel. A medial heel wedge or heel seat may reduce nerve traction by inverting the heel. Night splints, controlled ankle movement walkers (CAM walkers), or walking boots may be tried. Footwear with appropriate arch support may help reduce symptoms. Patients who fail to respond to other conservative treatments may temporarily be placed in a walking boot.

Ganglion cysts may be aspirated under ultrasound guidance. Corticosteroid injections into the tarsal tunnel may help reduce edema. Surgery is indicated if conservative management fails to alleviate the symptoms or if a definitive cause of entrapment is identified.[15] Patients with symptoms caused by a space-occupying lesion generally respond well to surgical management. Abnormally slow nerve conduction across the posterior tibial nerve is predictive of failed conservative therapy.

Surgical management involves flexor retinaculum resection from its proximal attachment near the medial malleolus down to the sustentaculum tali. Surgical success rates vary from 44% to 96%. Patients with a positive Tinel sign preoperatively tend to respond better to surgical decompression than those who do not. Younger patients and those with a short history of symptoms, early diagnosis, clear etiology, and no previous ankle pathology also respond well to surgery.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of TTS is broad and includes the conditions listed below. A thorough clinical examination and judicious use of diagnostic studies can help distinguish these conditions from TTS.

- Achilles tendonitis

- Deep flexor compartment syndrome

- Degenerative changes, such as calcaneal spurs and foot arthroses

- Inflammatory conditions of the foot and ankle ligaments and fascia

- Intersection syndrome of the FHL and FDL at the knot of Henry

- L5 and S1 nerve root compression

- Morton metatarsalgia

- Neurogenic intermittent claudication

- Plantar fasciitis

- Polyneuropathy

- Retrocalcaneal bursitis

Prognosis

The prognosis of TTS varies. The response is generally favorable in patients with an identifiable etiology, especially if diagnosed early in the disease course. Patients without an identifiable cause and who do not respond to conservative therapy generally do not do as well with surgical intervention. A positive Tinel sign is a strong predictor of surgical relief.

Complications

Untreated or refractory TTS can result in neuropathies of the posterior tibial nerve and its branches. Patients may have persistent pain, and muscle weakness and atrophy can develop. Postoperative complications include impaired wound healing, infection, and scar formation. Pain and other symptoms may not adequately resolve even with surgical decompression.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative rehabilitation protects the joint and nerve integrity and controls inflammation, pain, and swelling. As rehabilitation continues, the therapist and patient can work to prevent scar tissue contraction and adhesions and maintain soft tissue and joint mobility. Return to normal gait, walking, and running are long-term goals.

Consultations

TTS is a difficult, rare diagnosis to make. As such, cases are best managed by an orthopedic specialist. Depending on the etiology, surgical management may be indicated.

Deterrence and Patient Education

No clear guidelines exist for preventing TTS. However, the following general measures can help:

- Wear proper footwear.

- Avoid prolonged standing or walking.

- Maintain a healthy weight.

- Warm up and stretch before physical activities.

- Strengthen foot muscles.

- Avoid foot and ankle overuse.

- Keep workspaces ergonomically designed to reduce stress on the lower limbs.

- Maintain foot posture and alignment.

Patients should be aware that foot and ankle pain has many causes, some of which are uncommon, including TTS. Patients must be advised to seek immediate medical help if they develop foot and ankle pain and other concerning symptoms such as burning, numbness, tingling, and muscle weakness.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind when evaluating and managing TTS are as follows:

- TTS is an entrapment neuropathy of the medial ankle that can arise from various causes.

- TTS is an uncommon but underdiagnosed cause of foot and ankle pain.

- Patients present with pain from the tarsal tunnel radiating down to the plantar foot, though symptoms can vary.

- No diagnostic modality can specifically identify TTS. The diagnosis is clinical, but various studies can help rule out treatable causes.

- Conservative therapy can be tried in most patients.

- Surgical decompression can provide good results if a definitive cause amenable to surgery is identified.

No specific preventive guidelines have been established for TTS. However, at-risk patients should be advised to seek medical help immediately if symptoms arise. Early intervention can help prevent the progression of TTS and improve outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

TTS is best managed by an interprofessional team that consists of a primary care physician, radiologist, podiatrist, orthopedic surgeon, orthopedic nurse, and physical therapist. The primary care physician is often the first to examine the patient and provide initial treatment. These professionals also monitor patients on follow-up. The radiologist can interpret the imaging studies and help guide treatment decisions. The podiatrist and orthopedic surgeon can lend their expertise in diagnosing foot and ankle disorders and performing warranted procedures.

A physical therapist can help improve the patient's foot and ankle function and address other TTS manifestations like inflammation and pain. The orthopedic nurse monitors patients, administers medications, reinforces education, and coordinates care.

The overall prognosis for patients with tarsal tunnel syndrome is guarded. Relapse and remission are common, and some patients never achieve complete relief from symptoms.