Definition/Introduction

Most surgical or traumatic wounds require skin closure of some kind. Most commonly, this closure is done by suturing, as opposed to staples or surgical glues. A closure is a means of primary repair of skin and deeper layers (subcutaneous tissue, fascia, etc.) to promote wound healing. Suturing offers advantages like low dehiscence rates and greater tensile strength than other closure methods.[1][2]

Historically, some form of wound closure mechanisms have been employed and were very similar to modern sutures. Several thousand years before the common era (BCE), eyed needles, sometimes made of bone, were used to pass a suture through wounds. The suture materials included hemp, flax, hair, linen, pig bristles, grass, reeds, and other plants.[3] Sushruta described suturing with materials made of bark, tendon, hair, and silk in 500 BCE. Other famed surgeons also described using primitive sutures like Galen and Antyllus, as did Pare´and Lister.[4] At one point, the mouth of pincher ants was used to approximate wounds before the modern suture was devised, which became in vogue in the mid 20 century.[3][4]

Presently, there are innumerable options for sutures. Therefore, to appropriately choose a suture type, it is necessary to understand the characteristics of different sutures. The ideal sutures are easy for the surgeon to handle, provide appropriate strength and secure knots, can tolerate wound changes like swelling and recoil, cause minimal inflammation or infection risk, are easily visible, and are relatively inexpensive.[5][6][7][8] There is no known suture possessing all of these qualities. However, with good technique, proper choice for each incision can help improve aesthetic results.[2][5] Understanding all of the attributes of each type of suture is essential. To correctly choose, it is necessary to understand the differences between different filament types and different needles and in which clinical situations they are designed to be used.

Issues of Concern

There are many different types of sutures grouped by several different characteristics. Understanding these characteristics allows for ideal suture selection.

The main factors used to classify sutures types are:

- Absorbable vs. non-absorbable

- Synthetic vs. natural

- Monofilament vs. multifilament

The first main suture category is absorbable versus non-absorbable sutures. Sutures are considered absorbable if they lose most of their tensile strength over variable periods ranging from a few weeks to several months.[2][5][6][7] Absorbable sutures are often employed for deep temporary closure until the tissues heal or when it is not easy to remove them otherwise. In this fashion, they are useful for approximating edges of tissue layers, closing deep spaces or defects, and facilitating wound healing as part of a multi-layered closure.[1][2][5][9] When used superficially, they can have more inflammation, which can lead to more scarring. If using absorbable sutures superficially, the recommendation is that a rapidly absorbing suture is employed.[1]

Absorbable sutures can also classify as natural and synthetic sutures. Natural sutures are derived from purified animal tissues (usually collagen) and are sometimes made of the purified serosa of bovine intestines.[9][10] Silk and catgut (made from sheep submucosa) are all types of natural sutures.[2] Natural sutures differ from synthetic sutures in that they degrade (if absorbable, like catgut) by proteolysis, while synthetic sutures degrade by hydrolysis. Hydrolysis causes less of an inflammatory reaction than proteolysis, which is why natural sutures can be known for causing more inflammation at the suture site.[2][6][4][10] Catgut sutures can be treated with an aldehyde solution to strengthen the material (plain catgut sutures) and can undergo further treatment with chromium trioxide (which also strengthens and helps them last longer before absorption) like chromic catgut.[10]

Non-absorbable sutures are used for long-term tissue closure like vessel anastomosis, permanently ligating internal tubular structures or vessels, performing a second layer of bowel hand sawing anastomosis, hernia fascial defects closure, and other uses.[11][12][13]

Another important suture category is monofilament and multifilament. Monofilament sutures are single filaments (as their name implies) with less surface area than a multifilament (braided or twisted suture).[2][5][9] Monofilament sutures have higher memory which demands more handling care. Memory is the tendency of a suture to return to its original shape and makes the suture more prone to knot loosening. It should be addressed by holding the suture and slightly tugging it. They typically require more knots to ensure security but tend to fracture less than multifilament sutures. Monofilament sutures also pass through tissues more easily and cause a less inflammatory reaction than their multifilament counterparts.[2][9][10]

Conversely, multifilament sutures are more pliable; they hold knots more securely, have less memory, and are easier to handle by the surgeon. However, multifilament sutures also cause more friction through tissue and have increased capillarity and surface area, increasing their proclivity to inflammation and infection.[2][5][6][9] Multifilament sutures can be coated to make them slide through tissues more easily and have properties more similar to a monofilament suture. They can also be coated with antibiotics to make them more infection-resistant. However, they are more expensive than traditional sutures.[2][4]

Any suture can have the addition of a dye. The dye helps with suture visualization. However, if sutures are under the epidermis, it is preferable to have them undyed, so they are not visible.[2][4][6]

Most sutures have smooth surfaces. However, there are newer sutures manufactured with barbs. These barbs help approximate wounds and do not require knots for security. Barbed sutures more evenly distribute tension along the wound. These sutures are also known to be more time efficient.[2]

Another critical property of a suture is its tensile or breaking strength, which generally comes from suture width. Sutures are numbered by their size relative to their diameter. Thick suture numbering is from 0-10, with #10 being the largest diameter. Thin sutures are those that have the greatest number of zeroes after them and range from 1-0 to 12-0 (12-0 having the least breaking strength).[2][5][6][10] There is about a 0.01 to 0.05 mm diameter difference between sizes.

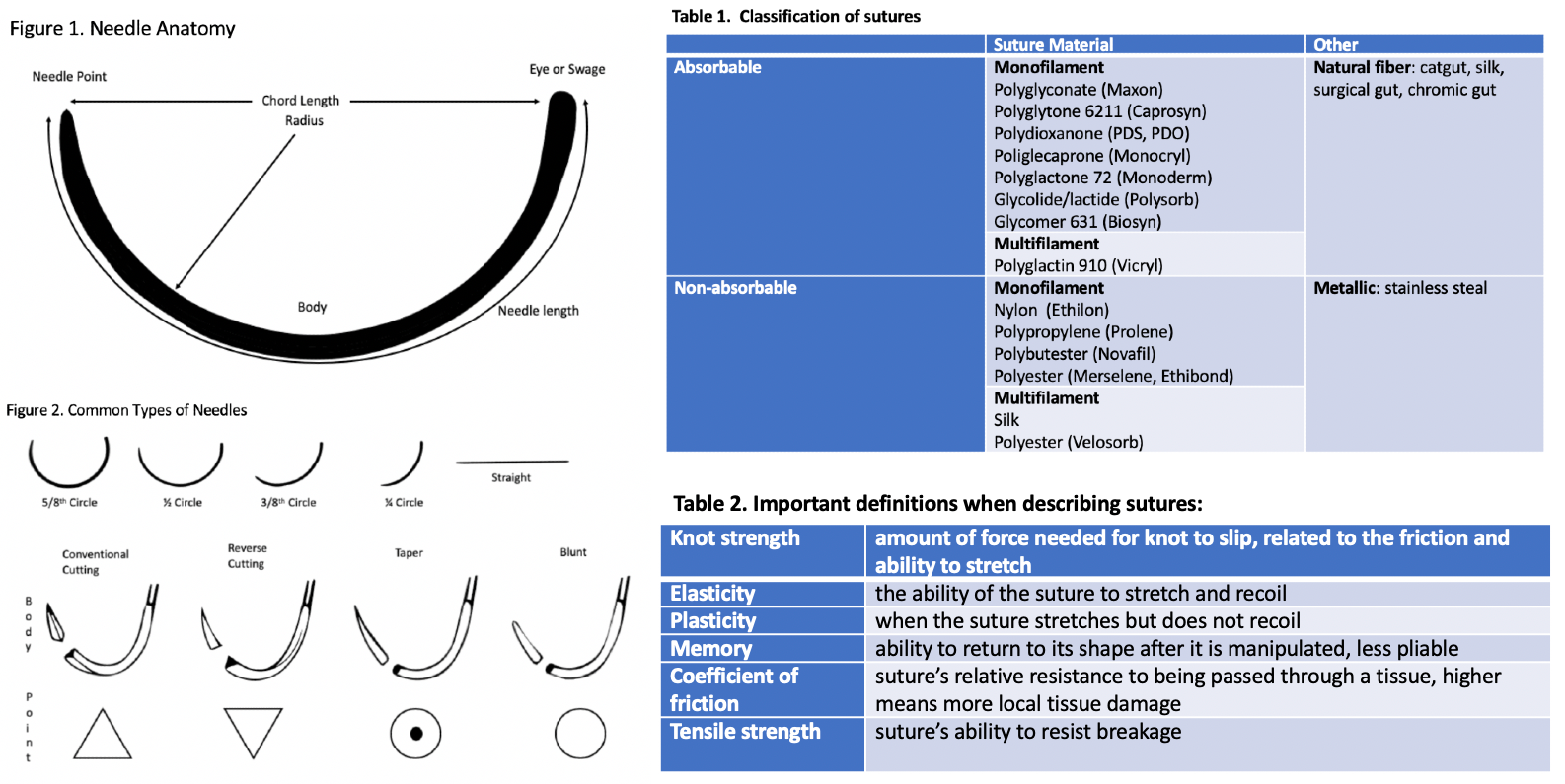

The next important aspect of sutures is the needle. The needle is made up of three main parts, the eye, body, and point.[2][5][10] The eye is where the suture attaches to the needle; this can be an actual needle eye, where the string threads through or a point where the suture thread gets swaged onto the needle (most modern needles are of this latter type). The body is the most substantial part of the needle and connects the eye to the point and determines the shape of the needle. The needle can be straight or curved, which is more common. The circle of a curved needle comes in different lengths, but most curves are 1/4, 1/2, 3/8, or 1/3 of a circle. The curve is vital in helping the surgeon know where the tip of the needle is at all times. Most skin closure sutures are curved and usually 3/8 of a circle.[2][5]

Amongst needles, there are different types based on the needle tip, mainly cutting or taper needles. Cutting needles have a tip with three sharp edges; a conventional cutting needle has the cutting surface inside the needle and a reverse cutting needle has it on the outside of the needle. Reverse cutting needles are commonly used for sewing skin.[5][3][6][9][10]

Taper needles are rounded and can be either sharp or blunt. They work by piercing the tissue without cutting it, essentially spreading the tissue as it passes through it. These are good for soft and delicate tissues and tendon repair. [5][6][10]

Examples

Natural Sutures: Plain Gut, Chromic Gut, Silk, Steel

Synthetic Sutures: Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl), Poliglecaprone 25 (Monocryl), Polydioxanone (PDS), Nylon (Ethilon, Dermlon), Polypropylene (Prolene, Surgipro)

Absorbable Sutures: Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl), Poliglecaprone 25 (Monocryl), Polydioxanone (PDS)

Non-absorbable Sutures: Nylon (Ethilon, Dermlon), Polypropylene (Prolene, Surgipro)

Monofilament Sutures: Nylon (Ethilon, Dermlon), Polypropylene (Prolene, Surgipro), Polydioxanone (PDS), Poliglecaprone 25 (Monocryl)

Multifilament Sutures: Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl), Silk, Nylon (Nuralon), Polyester (Tricon)

Barbed Sutures: Stratafix, Quill, Durabarb

Suture Removal

Sutures should be cut immediately under the knot during removal; this allows the least amount of skin surface contamination to be dragged through the inside of the wound when the suture is pulled out.

Table 1. Classification of sutures[2]

Table 2. Important definitions when describing sutures[5][6][10]

Figure 1. Needle Anatomy

Figure 2. Common Types of Needles

Clinical Significance

While there are many properties to sutures, it is most important to be able to determine which sutures are best for individual clinical scenarios. This determination depends on the thickness and location of the tissues, the amount of tension across the wound, and the risk of infection.[5][9] One must choose the caliber, type of filament (absorbable or non-absorbable), and the tissue and needle needs.

There is no specific algorithm for suture choice; however, a few rules are helpful. For instance, if there is a high infection risk, a monofilament absorbable suture is chosen. For running intradermal sutures, thin monofilament absorbable sutures with minimal reactivity are typically used.[9] When suturing the skin, particularly in cosmetically sensitive areas, the smallest suture for the area should be used.[9] Trials have shown no major differences between absorbable and non-absorbable sutures regarding cosmesis and complications, scars, and patient satisfaction.[8][14][15][16]

For absorbable sutures, if more strength is required, one can choose a suture with a longer absorption time. Slow healing tissues, like fascia and tendons, should be closed with non-absorbable or slow absorbing sutures, while faster healing tissues like the stomach, colon, and bladder require absorbable sutures.[11] Urinary and biliary tracts are prone to stone formation, so synthetic absorbable sutures are better in this situation, while sutures prone to digestive juices should be those that last longer. Natural sutures do very badly in the GI tract.[4][11][17] A non-absorbable suture is best when prolonged tension (fascial closure, tendon repair, bone anchoring, or ligament repair) is necessary for suitable healing.[10]

In general, surgeons typically use either polypropylene or polydioxanone sutures for fascia, depending on how strong the repair needs to be. Polypropylene is also very common in cardiovascular surgery. Deep dermis closure is with either polyglycolic acid or poliglecaprone 25 sutures. If closing the epidermis with a running subcuticular suture, poliglecaprone 25 is preferred. If one is performing interrupted sutures on the skin surface, nylon is ideal; polydioxanone for near dark hair and fast absorbing or chromic gut suture if it is on a child or in an area where sutures are difficult to remove. Many good choices exist depending on provider preference, experience, and the desired result.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Many interprofessional healthcare team members need to be familiar with suturing materials and techniques, especially since nurses, surgical assistants, and other personnel often perform suturing for the surgeon or other clinician or help remove sutures.