Continuing Education Activity

Supraventricular tachycardia refers to a group of rapid heart rhythm disorders originating at or above the atrioventricular node. Supraventricular tachycardia is characterized by a narrow QRS complex of less than 120 ms and an elevated heart rate. In adults, the heart rate exceeds 100 bpm, whereas in children, it can range from 180 to 220 bpm. Supraventricular tachycardia encompasses various atrial, junctional, and atrioventricular tachycardias, such as atrial ectopic tachycardia, atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation, and atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia.

This activity describes a comprehensive overview of supraventricular tachycardia, addressing its causes, underlying pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and current treatment approaches. Healthcare professionals gain insights into the complexities of supraventricular tachycardia and learn about both pharmacological and procedural management strategies, including the roles of catheter ablation and acute interventions. This activity equips participants with essential knowledge to effectively diagnose, manage, and support patients with supraventricular tachycardia.

Objectives:

Differentiate between subtypes of supraventricular tachycardia, such as atrial ectopic tachycardia, atrioventricular reentry tachycardia, and permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia, to guide appropriate management strategies.

Screen patients for potential reversible causes of supraventricular tachycardia, including electrolyte imbalances, structural heart disease, or medication effects.

Implement evidence-based treatment protocols for acute and long-term management of supraventricular tachycardia, including vagal maneuvers, pharmacotherapy, and, when necessary, synchronized cardioversion.

Coordinate follow-up care for patients with recurrent supraventricular tachycardia, ensuring timely access to specialty care and continuous monitoring of treatment efficacy and potential adverse effects.

Introduction

Supraventricular tachycardia is a general term for dysrhythmias originating at or above the atrioventricular node, characterized by a narrow QRS complex (<120 ms) with a heart rate exceeding 100 bpm, typically ranging from 150 to 220 bpm. Supraventricular tachycardia includes various conditions, including atrial, junctional (ectopic), and atrioventricular tachycardias.[1]

The most common types of supraventricular tachycardia are atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia and atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia. Both conditions are characterized by a rapid ventricular rate, which can significantly impact the patient's hemodynamic status.[2][3][4]

Etiology

The differential diagnosis includes sinus and ventricular tachycardia, which can be mistaken for supraventricular tachycardia with aberrant conduction. In individuals prone to supraventricular tachycardia, certain factors can trigger episodes, including medications, such as β-agonists for asthma; stimulants; caffeine; alcohol; and physical or emotional stress.[5][6]

Epidemiology

Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia has an incidence of 35 per 10,000 person-years, or 2.29 per 1000 individuals, making it the most common tachyarrhythmia among young adults. Women are at a 2-fold higher risk of developing paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia compared to men, whereas older individuals have a 5-fold increased risk compared to younger individuals.[7] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Atrioventricular Nodal Reentry Tachycardia," for more information.

Supraventricular tachycardia is the most common symptomatic arrhythmia in infants and children. Children with congenital heart diseases, such as the Ebstein anomaly of the tricuspid valve, are at higher risk for atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Atrioventricular Reciprocating Tachycardia," for more information. In addition, young adults who have undergone Fontan surgery or surgery for tetralogy of Fallot are at an increased risk for atrial arrhythmias. In children younger than 12, an accessory atrioventricular pathway causing reentrant tachycardia is the most prevalent cause of supraventricular tachycardia.[8][9]

Pathophysiology

Electrical impulses originate in the sinus node and travel through the surrounding atrial tissue to the atrioventricular node. At the atrioventricular node, there is typically a delay of about 100 to 120 ms at rest before the signals are transmitted through the His-Purkinje system. This system distributes the depolarization to the left and right bundles, ultimately reaching the myocardium and initiating myocardial contraction (see Image. Cardiac Electrical Conduction System). This pause at the atrioventricular node allows the atria to contract and empty their contents before the ventricles contract.

A narrow QRS complex (<120 ms) indicates that the ventricles are activated above the His bundle via the normal conduction pathway through the His-Purkinje system. In cases of a narrow complex tachycardia, the narrow QRS complex suggests that the arrhythmia originates from above the His-Purkinje system, which includes the sinoatrial node, the atrial walls, the atrioventricular node, or even within the His bundle itself.

When accessory pathways are involved in supraventricular tachycardia, the most common type is orthodromic reentry supraventricular tachycardia. In this scenario, the electrical signal travels antegrade through the atrioventricular node and retrograde via an accessory pathway that connects the ventricles to the atria, resulting in persistent tachycardia.[10]

Antidromic reentry supraventricular tachycardia is a less common type of supraventricular tachycardia, in which the impulse flows from the atria to the ventricles through an accessory pathway and returns retrogradely to the atria via the atrioventricular node or through a different accessory pathway or pathways.[11] This type of supraventricular tachycardia typically results in a wide QRS complex due to abnormal ventricle conduction.

Permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia is a rare type of supraventricular tachycardia characterized by a nearly continuous form of orthodromic atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia. This tachycardia typically involves a slow-conducting concealed accessory pathway located in the posteroseptal region of the heart. Permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia is more frequently observed in the pediatric population. Although it responds to adenosine, it often recurs, leading to misdiagnosis or ineffective treatment. Over time, this can result in the development of end-stage cardiomyopathy, with patients being diagnosed only when referred for a transplant.[12]

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is characterized by preexcitation, identified by a delta wave (a slurred upstroke to the QRS complex) and a prolonged QRS duration (>100 ms). When patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome develop supraventricular tachycardia, it is typically an orthodromic reentry tachycardia where the atrioventricular node serves as the antegrade limb and the accessory pathway functions as the retrograde limb of the supraventricular tachycardia. Without a baseline ventricular conduction delay, such as a bundle branch block, the QRS complex becomes narrow during supraventricular tachycardia in these patients. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome," for more information.

Occasionally, patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome may present with an antidromic reentry tachycardia, in which the accessory pathway acts as the antegrade limb, and the atrioventricular node or another accessory pathway functions as the retrograde limb of the reentry circuit during the supraventricular tachycardia. In this scenario, the QRS complex is wide, making the tachycardia resemble ventricular tachycardia.

In cases of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome with supraventricular tachycardia, atrioventricular nodal blocking agents, such as adenosine or calcium channel blockers, are contraindicated. If atrial fibrillation develops in these patients, these medications could lead to preexcited atrial fibrillation, allowing unopposed antegrade conduction through the accessory pathway, which may lead to ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death.[13]

History and Physical

Patients may present with symptoms such as palpitations, chest discomfort, lightheadedness, syncope, dyspnea, or anxiety. In some cases, they may present with shock, exhibiting hypotension or signs of heart failure if the supraventricular tachycardia has persisted for several hours or days. The onset of symptoms is typically sudden and can be triggered by stress, whether from physical activity or emotional strain. Termination of the episode typically occurs abruptly as well.

During a physical examination, a rapid pulse at rest may be observed, along with tachypnea, occasional pallor, and diaphoresis. Patients beginning to decompensate may show signs of congestive heart failure, such as bibasilar crackles, a third heart sound (S3), or jugular venous distension.

Evaluation

When suspecting supraventricular tachycardia, it is important to initially assess the patient for signs of hemodynamic instability beyond just tachycardia. Indicators such as respiratory distress, hypotension, altered mental status, or chest pain should be assessed. The diagnosis can be confirmed by obtaining an electrocardiogram (ECG) and identifying the rhythm.[14][15][16]

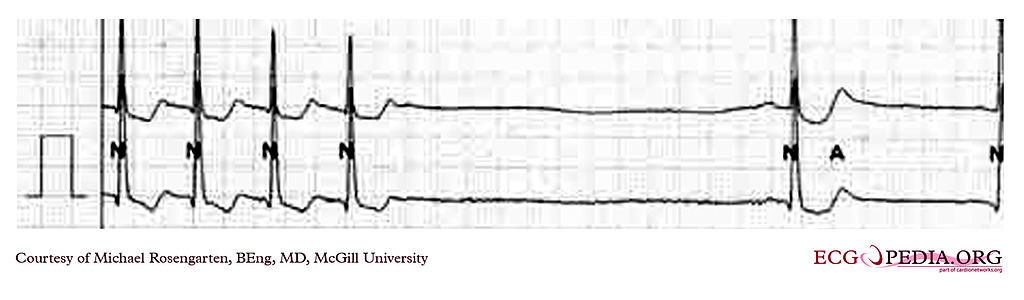

A typical ECG for atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia shows a narrow complex (QRS duration <120 ms) with regular tachycardia at a rate of approximately 180 to 220 bpm, often with no discernible P waves due to the near-simultaneous activation of the atria and ventricles (see Image. Supraventricular Tachycardia). If P waves are visible, they may present as a small deflection in the R wave of lead V1 (referred to as a pseudo-R' wave) or a small deflection in the S wave of the inferior leads (known as a pseudo-S wave).[17]

Other potential etiologies, such as atrial ectopic tachycardia or atrial flutter, can be considered if P waves are detected. If the patient's ECG in sinus rhythm is available, the QRS complex during supraventricular tachycardia should match the QRS complex observed in sinus rhythm.[10][18]

A wide complex tachycardia may indicate either ventricular tachycardia or a supraventricular rhythm with aberrant conduction. The latter can occur in cases of preexisting bundle branch block, electrolyte disorders, or a paced rhythm. Differentiating between supraventricular tachycardia and ventricular tachycardia is crucial, as the management strategies for each condition differ.

In addition, reversible causes of supraventricular tachycardia should be ruled out, including electrolyte imbalances, anemia, or hyperthyroidism. For patients on digoxin, checking the drug level is essential, as supraventricular tachycardia can result from supratherapeutic levels. However, it is important to note that digoxin toxicity can occur at therapeutic doses if hypokalemia is present.[19]

Treatment / Management

During supraventricular tachycardia, it is essential to assess for signs of hemodynamic instability. These signs include angina, hypotension, altered mental status, hypoxia, and evidence of poor end-organ perfusion or shock.

Treatment of Unstable Patients

For unstable patients, the heart fills during diastole, which typically accounts for two-thirds of the cardiac cycle. A rapid heart rate significantly shortens the time for the ventricles to fill, decreasing blood flow from the heart during systole. This reduction in blood ejection results in lower cardiac output, leading to hypotension.

As cardiac output drops, patients may exhibit symptoms such as hypotension, hypoxia, chest pain, dyspnea, altered mental status, or other signs of shock. These symptoms are more common when the heart rate exceeds 150 bpm. In cases where the patient is unstable, immediate synchronized cardioversion should be considered.

A defibrillator must be set to sync mode, typically indicated by a marker on the device's screen highlighting each QRS complex. This synchronization ensures that the shock is delivered in line with the QRS complex, preventing delivery during the T wave, which could trigger ventricular fibrillation, known as the R on T phenomenon.

For patients with supraventricular tachycardia, the appropriate shock voltage for cardioversion is between 50 and 100 J. In children, the initial dose for cardioversion is between 0.5 and 1 J/kg, which can be increased to 2 J/kg if necessary (see Image. Supraventricular Tachycardia Termination on Electrocardiogram Tracing). If time permits, anxiolysis or analgesia may be considered before cardioversion, but this should be done once the patient is stabilized.[13]

Treatment of Stable Patients

In stable patients, vagal maneuvers can be attempted while in the supine position as a preliminary approach before preparing for chemical cardioversion. These maneuvers stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system, helping to slow impulse formation at the sinus node, reduce conduction velocity at the atrioventricular node, and increase the refractory period of the atrioventricular node.

Although the Valsalva maneuver is generally accepted, carotid sinus massage should be avoided in both pediatric and adult populations, particularly in patients with bruits, a history of cerebrovascular disease, transient ischemic attacks, or those who have undergone endarterectomy. The Valsalva maneuver and the application of ice to the face can effectively treat hemodynamically stable supraventricular tachycardia in infants and children. When performed correctly, these techniques can be applied rapidly and safely without affecting any follow-up treatments if they prove unsuccessful.[20]

The oculocardiac reflex refers to a moderate bradycardic response to ocular pressure elicited by tension on the extraocular muscles.[21] Although it has been used as a vagal maneuver, it is now avoided due to the risk of ocular injury.

Pharmacotherapy with Adenosine

If vagal maneuvers are not effective, pharmacotherapy becomes necessary. The first-line medication for supraventricular tachycardia is adenosine, an endogenous nucleoside that creates a transient blockade of the adenosine A1 receptors. This blockage interrupts conduction through the atrioventricular node, disrupting the reentry circuit and allowing for restoration of the sinus rhythm.[22]

Continuous ECG monitoring during adenosine administration can help diagnose the mechanism of tachycardia in patients suspected of having focal atrial tachycardia. Adenosine is rapidly metabolized in the body and should be administered as a rapid intravenous push, preferably through a large peripheral vein.[23]

The adverse effects of adenosine are typically self-limited due to its short duration of action and quick metabolism. These adverse effects may include flushing, chest discomfort, and dyspnea. After administration of adenosine, transient arrhythmias may occur, such as sinus pauses, sinus bradycardia, asystole, and premature atrial or ventricular depolarizations. There have been case reports of bronchoconstriction following adenosine administration, particularly in patients with preexisting obstructive lung disease.[24]

Notably, methylxanthines, such as caffeine and theophylline, can negate the effects of adenosine.[25] Adenosine is not contraindicated in pregnant or lactating patients, as it is believed to be rapidly metabolized and poses a low risk to a fetus or nursing infant due to its natural presence in the body.[26]

Synchronized Cardioversion

Intravenous or oral β-blockers, diltiazem, or verapamil are suitable options for the acute treatment of hemodynamically stable patients with supraventricular tachycardia. For hemodynamically stable patients with atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, intravenous amiodarone may be considered when other therapies are ineffective or contraindicated. Synchronized cardioversion is recommended for hemodynamically stable patients with atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia if pharmacological treatment does not terminate the tachycardia or is inappropriate.[13]

If these measures are ineffective, overdrive pacing—where the heart is paced at a faster rate than its natural rhythm—can help terminate supraventricular tachycardia. However, this approach carries an increased risk of ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation; therefore, it should be used cautiously, with cardioversion readily available.

Patients with recurrent supraventricular tachycardia without preexcitation may require long-term maintenance therapy with oral β-blockers or calcium channel blockers to maintain sinus rhythm.[10] In patients with recurrent supraventricular tachycardia who also have structural or ischemic heart disease, the use of flecainide or propafenone may be beneficial.[27][28] Intravenous amiodarone may be considered for the acute treatment of hemodynamically stable adults and pediatric patients with supraventricular tachycardia when other therapies are ineffective or contraindicated.[13][20]

Notably, adenosine does not terminate supraventricular tachycardias when the atrioventricular node is not part of the reentry circuit, such as in cases of atrial ectopic tachycardia, atrial flutter, and atrial fibrillation. In addition, adenosine is typically ineffective in terminating ventricular tachycardia.[29]

Interventional Options

Radiofrequency or cryoablation of an atrial focus can effectively treat atrial tachycardia. In cases of atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, the procedure targets the slow atrioventricular node pathway. For atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia, ablation may be performed on one or more accessory pathways. These approaches can provide a definitive solution, potentially eliminating the need for long-term medication.[30]

Paroxysmal Junctional Reentrant Tachycardia

Many infants and children require treatment with multiple antiarrhythmic medications. Options include β-blockers, diltiazem, and verapamil.[13] Some studies suggest that combination therapy using flecainide and amiodarone may be more effective in controlling tachycardia and reversing cardiomyopathy, particularly when the condition is diagnosed and treated early. Catheter ablation is considered the most effective treatment option when accurate cardiac mapping is performed.[12]

Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome

For the acute treatment of hemodynamically unstable patients with preexcited atrial fibrillation, synchronized cardioversion is recommended. Small observational studies suggest that ibutilide or intravenous procainamide can be effective in treating preexcited atrial fibrillation in patients with hemodynamic stability.[13]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for supraventricular tachycardia includes sinus tachycardia and ventricular tachycardia.

Prognosis

Most patients with paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia generally have a good outcome with treatment. For individuals with structural cardiac defects, the prognosis varies depending on the specific type of defect. Healthy individuals without structural defects have an excellent prognosis. Notably, pregnant patients who develop supraventricular tachycardia face a slightly increased risk of complications, particularly if they have an unrepaired heart defect.[31][32][33]

Untreated permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia can result in tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy, a condition that can be reversed with appropriate treatment.[34] Early diagnosis and intervention are crucial to prevent long-term cardiac damage and improve overall outcomes for affected patients.

Complications

Complications may arise from medications, such as β-blockers, diltiazem, verapamil, and amiodarone, or from the radiofrequency and cryoablation procedures. Potential complications associated with these procedures include:

- Hematoma

- Pseudoaneurysm of the artery

- Bleeding

- Myocardial infarction

- Heart block and the need for a pacemaker

- Stroke

- Death

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated on lifestyle modifications to help prevent triggers of supraventricular tachycardia. Common triggers include caffeine, alcohol, and stimulant use. Limiting or avoiding these triggers can help reduce the frequency of attacks.

Other lifestyle modifications include maintaining a healthy weight and avoiding dehydration. Regular exercise, balanced nutrition, and adequate fluid intake can improve cardiovascular health.

Medication adherence is crucial for effective management. Antiarrhythmics and β-blockers should be taken as prescribed. Patients should be educated about the potential adverse effects of these medications and report any symptoms to healthcare providers during follow-up care. If symptoms are severe or do not resolve with self-care measures, the patient should be advised to go to the emergency room immediately.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind about supraventricular tachycardia include the following:

-

Ventricular tachycardia is an umbrella term for tachycardias that originate above the ventricles. Common forms include atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia, and atrial tachycardia.

-

Most supraventricular tachycardias are due to reentrant circuits involving the atrioventricular node or accessory pathways.

-

Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia involves a reentry circuit within the atrioventricular node. In contrast, atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia, as in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, consists of an accessory pathway between the atria and ventricles.

-

Supraventricular tachycardia typically presents as a narrow complex tachycardia (QRS duration <120 ms).

-

A wide complex QRS may indicate an antidromic pathway or aberrant conduction.

-

Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia on ECG typically shows regular, narrow QRS complexes with a rate of 150 to 220 bpm; P waves may be absent or hidden within the QRS complex.

-

Symptoms of supraventricular tachycardia can include palpitations, chest pain, lightheadedness, dyspnea, and anxiety.

-

Hemodynamic instability is indicated by hypotension, altered mental status, hypoxia, or shock and warrants immediate intervention.

-

For stable patients, attempt vagal maneuvers, such as Valsalva, which can terminate atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia.

-

Adenosine is the first-line medication for acute supraventricular tachycardia, especially if atrioventricular node involvement is suspected.

-

Synchronized cardioversion is indicated for hemodynamically unstable patients with supraventricular tachycardia.

-

Adenosine temporarily blocks the atrioventricular node and helps diagnose and treat atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia and atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia. However, it is ineffective for atrial tachycardia, atrial flutter, or atrial fibrillation.

-

β-blockers; calcium channel blockers, such as diltiazem and verapamil; and intravenous amiodarone may be considered in refractory cases.

-

Patients with recurrent supraventricular tachycardia may benefit from β-blockers or calcium channel blockers.

-

Catheter ablation is an effective definitive treatment for recurrent or symptomatic cases, particularly atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia, and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.

-

Prolonged untreated supraventricular tachycardia may lead to tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy.

-

Caution should be exercised with digoxin toxicity in patients on digoxin, as it can precipitate supraventricular tachycardia or atrial tachyarrhythmias, especially with hypokalemia.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A cardiologist or cardiac electrophysiologist specializing in heart arrhythmias manages paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. As these arrhythmias cannot be prevented, treatment is the primary focus. Most patients experience a sudden onset of symptoms, so diagnosis and management typically occur in an acute care setting.

Various healthcare team members play vital roles in the diagnostic process. The emergency care physician suspects or makes the initial diagnosis, nurses establish intravenous access and administer medications, pharmacists prepare the medications, and nurses and technicians monitor the patient using continuous ECG. Pharmacists also play a key role in educating patients about potential adverse effects, drug interactions, and the importance of follow-up care for those prescribed medications.

For patients with recurrent supraventricular tachycardia or who do not respond well to medications, catheter ablation is an effective treatment option. This procedure, which has a high success rate, is typically performed by experienced electrophysiologists and can often eliminate the need for long-term medication.