Introduction

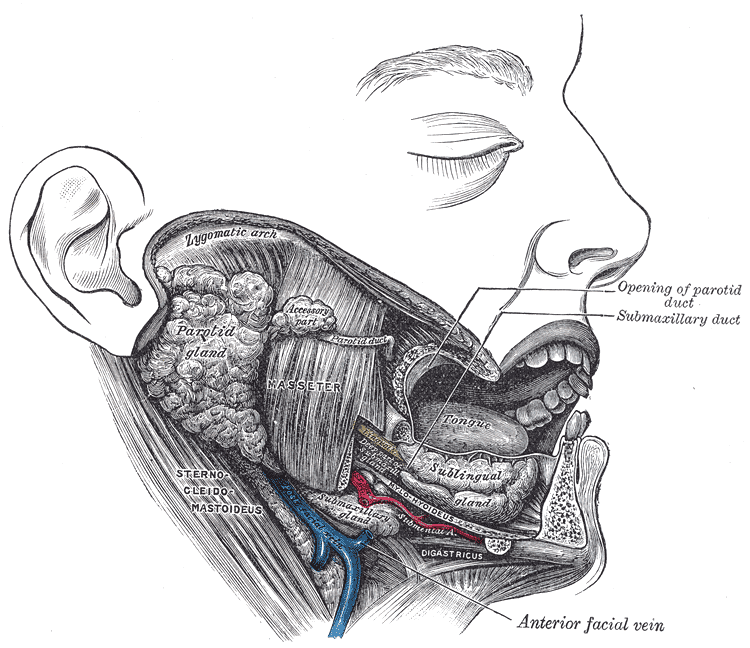

The submandibular gland is the second largest of the 3 main salivary glands, including the parotid and sublingual glands. The submandibular glands are paired with major salivary glands in the submandibular triangle (see Image. Submandibular Triangle). The glands have a superficial and deep lobe separated by the mylohyoid muscle [1]. The Wharton duct, the submandibular gland’s primary excretory duct, drains into the oral cavity at the sublingual caruncle. The sublingual caruncle is a papilla located medial to the sublingual gland and lateral to each side of the frenulum linguae [1]. The submandibular gland produces approximately 70% of the saliva in the unstimulated state. However, the parotid gland’s saliva production predominates once the salivary glands become stimulated (see Image. The Mouth, Dissection).[2]

Structure and Function

The submandibular gland is the second largest salivary gland (only the parotid gland is larger). The submandibular gland is in the posterior portion of the submandibular triangle, formed by the body of the mandible superiorly, the anterior belly of the digastric muscle medially, and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle inferiorly and laterally. The submandibular gland is surrounded by a capsule, which is a part of the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia. Like the parotid gland, the submandibular gland subdivides into superficial and deep lobes, separated by the mylohyoid muscle. The larger superficial lobe lies beneath the deep cervical fascia [3]. The submandibular gland’s main excretory duct is the Wharton duct. This duct has been measured to be approximately 5 cm long and 1.5mm in diameter. The Wharton duct originates at the submandibular gland hilum and then travels around the posterior portion of the mylohyoid muscle. The duct then crosses paths medially with the lingual nerve while traveling superiorly, eventually opening into the oral cavity at the sublingual caruncula. The sublingual caruncula is located on the floor of the mouth and is on either side of the lingual frenulum [2].

In general, saliva production lubricates the oral cavity, which allows for swallowing, initiating digestion, pH buffering, and dental hygiene. The submandibular gland tissue is a branched tubuloacinar gland composed of mucinous and serous acini. When the acini are grouped with their ducts, they are called adenomeres. Serous adenomeres predominate over mucous adenomeres in the submandibular gland, though the mucous cells are more active, which produces a slightly thicker fluid. The submandibular gland produces the most saliva (approximately 70%) in the unstimulated state; however, during salivary gland stimulation, the parotid gland produces more than 50% of the saliva [3]. The mucinous acini’s primary protein is mucin, which lubricates and competitively inhibits bacterial attachment to the salivary duct epithelium, allowing for antimicrobial protection of the submandibular gland. The serous acini’s primary protein is amylase, which functions to help metabolize starches in the oral cavity [2]. The composition of saliva depends on the salivary flow rate and can vary given each gland's flow rate and overall contribution. Saliva is made up of organic and inorganic components. Inorganic components include electrolytes, urea, and ammonia. The organic components of saliva consist of immunoglobulins, enzymes, and proteins [2].

Embryology

The submandibular gland develops after the parotid gland in the sixth week of prenatal development. The gland originates from epithelial buds surrounding the sublingual folds on the floor of the mouth. These epithelial buds develop into solid cords, which canalize to form the submandibular ducts. The striated and intercalated ducts develop by 16 weeks, and the acinar cells predominate by 24 weeks [4].

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood Supply

The submandibular glands receive their primary blood supply from the submental and sublingual arteries, which are branches of the facial artery, and the lingual artery, which are branches of the external carotid artery. The facial artery leads a tortuous path, passing through the gland capsule before crossing over the inferior border of the mandible. The common facial and sublingual veins drain the gland and flow into the internal jugular vein.

Lymphatics

The lymph nodes associated with the submandibular gland are not within the gland’s capsule but instead are located adjacent to the submandibular triangle. The submandibular lymphatics comprise 3 to 6 nodes beneath the body of the mandible. The nodes are palpable on the superficial surface of the submandibular gland. Malignant tumors may drain into these regional lymph nodes, requiring more extensive neck dissection for the complete treatment of cancer.

Nerves

The submandibular glands receive their parasympathetic input via the chorda tympani nerve, a branch of the facial nerve, via the submandibular ganglion. The nerve functions in a secretomotor capacity. The chorda tympani branches from the motor branch of the facial nerve in the middle ear cavity, which then exits the middle ear through the petrotympanic fissure. The chorda tympani nerve then travels with the lingual nerve to synapse at the submandibular ganglion. The chorda tympani carry the submandibular ganglia's pre-ganglionic fibers. The post-ganglionic fibers reach the submandibular gland and release acetylcholine along with other neurotransmitters, such as substance P and neuropeptide Y. Acetylcholine, the primary neurotransmitter, and the muscarinic receptors, work to stimulate myoepithelial cell function and salivary secretion [4]. Sympathetic nerve cell bodies are located in the superior cervical ganglion and extend post-ganglionic fibers that travel with external carotid artery branches to innervate the submandibular gland. Sympathetic input also increases salivary secretion and can induce local inflammation [4].

Surgical Considerations

An operation to excise the submandibular gland usually involves electrocautery and dissection by a transcervical, transoral, or endoscopic approach. Structures most at risk of injury during submandibular gland excision are the intracapsular facial artery and vein, the overlying marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve, and the hypoglossal and lingual nerves medially [4].

Clinical Significance

Neoplasia

Neoplastic disease may affect the submandibular gland, though it makes up less than 2% of all head and neck cancers [5]. Approximately 50% of submandibular gland tumors are malignant. Adenoid cystic and mucoepidermoid carcinomas are the most common submandibular gland malignancies reported. Metastasis to the major salivary glands can occur, commonly associated with primary head and neck cancers. Most tumors present with an asymptomatic swelling in the floor of the mouth or inferior mandible and present similarly to benign conditions, making diagnosis difficult. Evaluation often includes cross-sectional imaging and ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy. Treatment course may include submandibular gland excision for benign tumors and some low-grade malignancies. Selective neck dissection and adjuvant radiation therapy are therapeutic approaches for advanced tumor staging or aggressive pathologies. Chemotherapy is a less common choice in salivary malignancies [5].

Sialolithiasis

Salivary stones obstructing an excretory duct is a common salivary gland disease. The pathophysiology of salivary stones is related to salivary stasis and overall inflammation of the excretory duct. Salivary stones may cause swelling of the duct or gland, causing colicky peri-prandial pain. Salivary stones are manually palpable when lodged in a duct. Ultrasound can aid in diagnosis, adjunctive CT, and MR sialography if the workup is negative, but clinical suspicion should remain high. Initial treatment is conservative, which comprises oral hydration and sialagogues. Surgery is only recommended when conservative treatment fails and symptoms persist [2]. About 80% to 90% of salivary stones are found in the Wharton duct and are thought to originate from the submandibular gland. The primary etiology for this observation is salivary stasis, which is attributable to 2 factors. First, the Wharton duct is longer and more vertically angulated than the parotid duct, leading to increased salivary stasis. Second, as discussed above, the submandibular gland tissue is composed of mucinous and serous acini, which produce a more viscous fluid, adding to the mechanical stasis caused by the Wharton duct [2].

Sialadenitis

Sialadenitis is salivary gland inflammation caused by infection and obstruction by stones or microorganisms, most commonly Staphylococcal bacteria or the mumps virus. If sialadenitis occurs in the submandibular gland, there is a higher likelihood that salivary stones may be causing the inflammation; this is due to the partially viscous and serous saliva composition of the submandibular gland and possibly attributed to the salivary stasis caused by Wharton’s duct discussed above. Due to the higher likelihood of an obstructing pathology, radiographs, and CT imaging may be of more value to help identify a radiopaque obstructing stone. It is also important to rule out Ludwig’s angina through a clinical exam and imaging [2]. Fever, pain, and gland swelling may accompany the inflammation. If the etiology is a bacterial infection, then antibiotics are recommended. Otherwise, oral hydration and sialagogues are the recommended approaches. Surgical intervention may be required if abscess formation complicates the infection [2].

Sialadenosis

Sialadenosis is a benign, noninflammatory enlargement of the submandibular glands. It is a more common presentation in patients with malnutrition-associated diseases such as bulimia or diabetes. Patients with advanced liver disease due to alcoholic and non-alcoholic cirrhosis are also, particularly at higher risk for sialadenosis. The pathogenesis underlying sialadenosis is believed to be primarily caused by autonomic neuropathy. The gland’s secretory granules can accumulate in acinar cells, disrupting the glands' autonomic innervation [6].