Introduction

Three layers called the meninges encase the brain and spinal cord. From superficial to deep, these layers are the dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater. The dura mater is a dense connective tissue layer that is adherent to the inner surface of the skull. Next is the arachnoid mater that is a thin impermeable layer, and the innermost is the pia mater, which is a vascular layer that closely invests over the brain and spinal cord.[1] These membranes define three potential clinically significant spaces: the epidural space, which exists between the skull and the dura mater; the subdural space, found between the dura mater and arachnoid mater; and the subarachnoid space, which is between the arachnoid mater and pia mater. The epidural space in the skull is a potential space, while it is actually present in the spinal cord. The subarachnoid space consists of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), major blood vessels, and cisterns. The cisterns are enlarged pockets of CSF created due to the separation of the arachnoid mater from the pia mater based on the anatomy of the brain and spinal cord surface. The cisterns are created due to the close and firm adherence of the pia mater to the brain and spinal cord surface while rather loosely to the arachnoid mater.

Structure and Function

Anatomically, the subarachnoid space exists between the arachnoid mater externally and pia mater internally. A network of fine delicate connective tissue called trabeculae connects these two layers and gives this space its characteristic spider web appearance. The subarachnoid trabeculae act as supportive pillars between the pia mater and arachnoid mater, and due to the curtain-like structure with holes, it allows the flow of CSF.[2] Besides trabeculae, there are major cerebral blood vessels that penetrate the nervous tissue within this space.

The subarachnoid space does not have a uniform depth across the central nervous system and forms extensions around the neurovascular structures, spaces, and cisterns. It forms sleeve-like extensions around the cranial and spinal nerves and terminates where the pia mater and the arachnoid mater fuses with the perineum of these nerves. Besides, this space surrounds the arteries and veins of the central nervous system up to the point where they penetrate the nervous tissue and divide into arterioles and venules. While the pia mater closely adheres to the surface of the brain and follows the contours of cortical sulci and gyri, the arachnoid mater only bridges over the sulci, resulting in the formation of CSF filled triangular spaces. Also, at some places where the brain draws away from the skull because of its natural variation in shape, the arachnoid mater and the pia mater are not in close approximation. This results in naturally enlarged CSF filled expansions called the subarachnoid cisterns. These expansions transmit intracranial vessels along with cranial nerves and hold significant clinical relevance.[3] Although theses cisterns are commonly described as separate compartments, they are not truly anatomically separate. They are in free communication with each other and with the rest of the subarachnoid space. Some major cisterns include[4]:

1) Cistern of the lamina terminalis:

It is located anterior to the third ventricle and contains the anterior cerebral arteries, the anterior communicating artery, the hypothalamic artery, Heubner's artery, and the origin of the fronto-orbital arteries.

2) Sylvian cistern:

Also known as the insular cistern, is found in the fissure between the temporal and frontal lobes. It contains the middle cerebral artery and vein and the fronto-orbital veins.

3) Suprasellar cistern:

Also known as the chiasmatic cistern contains the anterior aspect of the optic chiasm, optic nerves (cranial nerve II), the hypophyseal stalk, and the origin of the anterior cerebral artery.

4) Interpeduncular cistern

Located between the two cerebral peduncles of the midbrain. It communicates inferiorly with the pontine cistern and superiorly with the chiasmatic cistern and contains the bifurcation of the basilar artery, peduncular sections of the posterior cerebral artery and superior cerebellar artery, the posterior communicating arteries that connect with the peduncular segments of the posterior cerebral arteries, the basal vein and the oculomotor nerve (cranial nerve III).

5) Superior cistern

Located posterolateral to the midbrain. Its lateral extensions connect it to the interpeduncular cistern. It contains the great cerebral vein, the third part of the posterior cerebral arteries and the superior cerebellar arteries. Its infratentorial portion contains the trochlear nerve (cranial nerve IV).

6) Pontine cistern:

It is located anterior to the pons and receives CSF from the paired foramen of Luschka (lateral aperture) of the 4th ventricle. It contains the basilar artery, the origin of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, the origin of the superior cerebellar artery, and the abducens nerve (cranial nerve VI).

7) Cerebellopontine cistern:

Situated in the lateral angle between the pons and the cerebellum. It contains the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII), the vestibulocochlear nerve (cranial nerve VIII), the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V), and the anterior inferior cerebellar artery.

8) Cerebellomedullary cistern:

Also known as the cisterna magna is the largest subarachnoid cistern. It is located between the medulla oblongata and the cerebellum. It receives CSF from the fourth ventricle through foramen of Magendie (median aperture). It contains the vertebral artery, the origin of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, the glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX), vagus nerve (cranial nerve X), accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI) and hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII).

9) Lumbar cistern:

It is located at the lower lumbar spinal canal. It extends from the conus medullaris around the level of the first and second lumbar vertebrae to the level of the second sacral vertebra. It contains the filum terminale and the cauda equina. During lumbar puncture, the clinician draws CSF from this cistern.

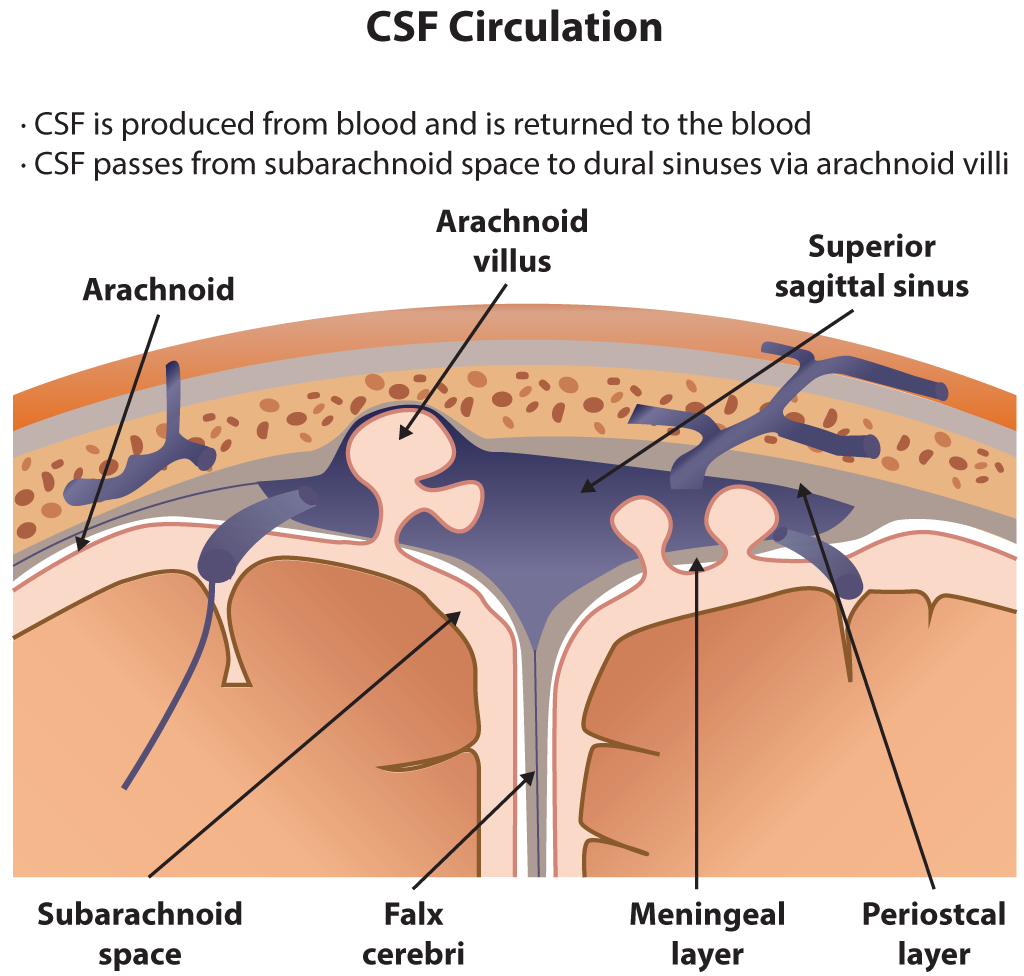

Functionally, the CSF flows within the subarachnoid space and the ventricular system. The choroid plexus primarily secretes the cerebrospinal fluid at a rate of 0.3 ml/min, and there are roughly 150 ml of CSF circulating at any given time.[5] While the ventricular system contains 25 mL, the rest is present within the subarachnoid space. A smaller amount of CSF is also secreted by the ependymal lining of the ventricles and the dura mater of the nerve roots sleeves in the spinal canal.[3] After production, CSF flows from the lateral ventricles through the left and right foramen of Monro and enters the third ventricle. Next, it flows into the fourth ventricle through the cerebral aqueduct. After that, CSF flows into the subarachnoid space through the foramen of Lushka laterally and foramen of Magendie medially. It flows superiorly and inferiorly overlying the cerebral cortex and spinal cord.[6] Eventually, it reaches the arachnoid granulations that are projections of the arachnoid mater into the superior sagittal sinus and act as an avenue for reabsorption of CSF into the blood through a pressure-dependent gradient.

Embryology

Research conducted on animal models reveals that the meninges of the forebrain originate from the neural crest cells and of the brainstem originates from the cephalic mesoderm. While the somatic mesoderm gives rise to spinal meninges, the formation of the primitive subarachnoid space begins with the closure of the neural tube, and by the tenth day of fetal development, it surrounds the telencephalon. However, it is not yet CSF filled and appears as an extracellular mass of mesenchyme that is composed of stellate mesenchymal cells with glycosaminoglycan substance. By the thirteenth day of fetal development, the CSF begins to seep in and replaces the ground substance of the mesenchyme peripherally. Typically, the subarachnoid space completely forms by the twenty-first day of infancy after birth.[7]

Surgical Considerations

The subarachnoid trabeculae and cistern are of great importance during neurosurgical procedures. The topography of the cisterns is of considerable significance during neurosurgery to preclude injury to the neurovascular structures. During surgery, careful sectioning of the trabeculae allows easy mobilization of the brain without retraction and protection of cranial nerves, arteries, and veins within the subarachnoid cisterns.[2]

Clinical Significance

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

The subarachnoid space is susceptible to blood collection secondary to damage to any of the cerebral blood vessels that travel close to the brain surface beneath the arachnoid mater. Most subarachnoid hemorrhages (SAH) are traumatic in nature, while a small portion of cases is the result of vascular malformations like aneurysms. During the hemorrhage, the build-up of clotted blood and fluid within the rigid skull not only irritates the lining of the brain but also increases pressure on the brain surface, which can lead to shift and herniation. Also, the part of the brain previously supplied with oxygen-rich blood from the affected artery now suffers from ischemia. Furthermore, blockage of the normal CSF circulation can enlarge the ventricular system (hydrocephalus) and lead to symptoms like loss of consciousness, lethargy, and confusion. After 5 to 10 days, the irritating by-products of blood cause the arterial walls to contract, resulting in vasospasm or decrease in lumen diameter of the artery. This condition leads to an interruption in blood flow, causing a secondary stroke.[8]

The hallmark symptom of SAH is thunderclap headache, and typically the patient calls it the "worst headache of my life." Additionally, the patient may also complain of nausea, seizures, vomiting, and diplopia. The initial diagnosis is confirmed by imaging, typically a CT scan of the head. If the CT scan is normal, but the clinical suspicion is high, an alternative way to establish the diagnosis is a lumbar puncture for CSF analysis. This test typically reveals xanthochromia or yellowish appearance of the CSF, which is evidence of blood or its products within the CSF. A CT angiography should be included in the evaluation if there is SAH present. Management of SAH varies depending on the underlying cause and the extent of brain damage and typically provides symptom relief (pain medications and anticonvulsants), repair of the damaged vessel (surgery), and preventing complications.[9]

Papilledema

The sheath of the optic nerve is continuous with the brain's subarachnoid space. In the event of raised intracranial pressure, there is relative sparing of the brain itself from the detrimental consequences of high pressure. However, the increased pressure is transmitted through to the optic nerve, creating protrusion and pinching of the optic nerve at its head. The retinal ganglion cells' fibers at the optic disc become engorged and bulge forward. Long-standing optic disc edema can eventually lead to loss of fibers and permanent visual damage.[10]