Introduction

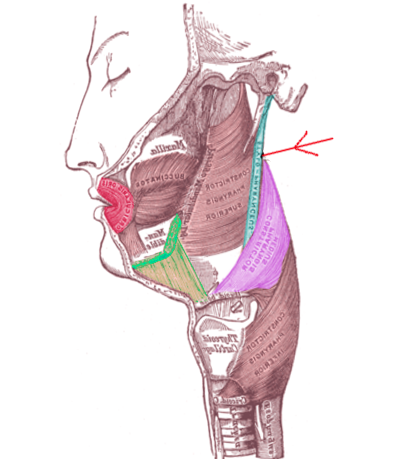

The stylopharyngeus muscle is a long, slender and tapered longitudinal pharyngeal muscle that runs between the styloid process of the temporal bone and the pharynx and functions during the pharyngeal phase of swallowing. The stylopharyngeus muscle, along with two other styloid muscles, i.e., the styloglossus muscle and the stylohyoid muscle, form the ‘bunch of Riolanus.’ It is the most vertical and medial among all the three styloid muscles.[1]

Structure and Function

The stylopharyngeus muscle plays an active role in elevating the larynx, pharynx, and in dilating the pharynx. This movement allows the passage of a large food bolus, thereby facilitating swallowing. Elevation of the pharynx causes compression of the lateral laryngeal walls, which further leads to the compression of the pharynx over the food bolus during deglutition.[2]

The stylopharyngeus muscle act as a significant dilating muscle of the nasopharynx. During breathing, the contraction of this muscle pulls the nasopharyngeal wall dorsally. This action prevents the dynamic collapse of the dorsal wall of the nasopharynx by supporting the wall during inspiration. There are three longitudinal muscles of the pharynx (stylopharyngeus, palatopharyngeus, and salpingopharyngeus), among which contraction of the stylopharyngeus muscle is the most effective for pharyngeal clearance.

Embryology

The stylopharyngeus muscle has its embryonic origin from the mesodermal derivative of the third pharyngeal arch. It starts forming between the fourth and seventh weeks of gestation.[2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The pharyngeal branch of the ascending pharyngeal artery (branch of external carotid artery) supplies the stylopharyngeus muscle. The lymphatic drainage of this region is via the middle posterior cervical nodes into the supraclavicular node group.

Nerves

All the muscles of the pharynx receive innervation from the tenth cranial nerve (vagus nerve) except the stylopharyngeus, which is innervated by the ninth cranial nerve (glossopharyngeal nerve). From the nucleus ambiguous that lies in the floor of the fourth ventricle, motor fibers travel in the glossopharyngeal nerve and innervate the muscle. After its exit from the cranial cavity, the glossopharyngeal nerve descends in the neck, running anterolaterally to the internal carotid artery. On reaching the inferior margin of the stylopharyngeus muscle, the nerve gives off several branches that provide motor innervations to this muscle.

Muscles

The stylopharyngeus muscle originates from the medial side of the base of a bony projection from the temporal bone, i.e., the styloid process.[1] It is the only pharyngeal muscle that has an origin outside the pharyngeal wall. It runs in a downward direction between the external and the internal carotid arteries. During its course, it penetrates the pharyngeal wall between two pharyngeal muscles (superior constrictor and the middle constrictor). There it runs in a longitudinal direction running deep to the superior constrictor muscle and superficial to the middle constrictor muscle. On the lateral pharyngeal wall, the stylopharyngeus muscle lies posterior to the superior constrictor muscle and anterior to the buccopharyngeal fascia.

Some of the fibers of the stylopharyngeus muscle become lost in the superior and middle constrictor muscles. Some fibers merge with the lateral glossoepiglottic fold while others join with the fibers of the palatopharyngeal muscle and insert into the posterior border of the thyroid cartilage/lamina.

The stylopharyngeus muscle has a topographical relationship with the piriform recess, which is the major route for pharyngeal swallowing and serves as the largest pocket providing post-deglutition retention. The lateral border of this recess (lateral glossoepiglottic fold or pharyngoepiglottic fold) is composed of the stylopharyngeus muscle and the palatopharyngeus muscle.

The ninth cranial nerve curves around the posterolateral border of the stylopharyngeus muscle to pass between the superior and middle constrictor muscles and reach the tongue.

Physiologic Variants

Various studies have mentioned the presence of the supernumerary muscles of the pharynx that originate from the petrous portion of the temporal bone and get inserted on the superior constrictor muscle. This muscle is known as the petropharyngeus muscle. Apart from the petropharyngeus, other variations of the stylopharyngeus muscle may also be present such as the occipitopharyngeus, mastoidopharyngeus, and the azygopharyneus. These supernumerary muscles have been thought to play a role in abnormal swallowing, pharyngeal clearance, phonetics, modulation of respiration, obstructive sleep apnoea, and dysphagia.

Studies have also reported the presence of an additional muscle sheet of the stylopharyngeus muscle that inserts into the tonsillar bed. These muscle fibers are short in the course and intermingle with the palatopharyngeus muscle and the superior constrictor of the pharynx. The incidence of occurrence of this additional muscle is high in females compared to that in males; this may be the result of aging, which may cause degenerative changes in the main stylopharyngeus muscle (descending bundle). Unlike the descending bundle, the additional insertion does not contribute to pharyngeal clearance. Their function is to pull the tonsillar bed dorso-superiorly.[3]

Surgical Considerations

In lateral pharyngoplasty, during the myotomy of the superior constrictor muscle, particularly the inferior portion, part of the stylopharyngeus muscle fibers may get cut. The total preservation of the stylopharyngeus muscle during the surgical procedure provides better results with a complete return to normal deglutition within few days.[4]

The procedure of tonsillectomy may induce scarring that involves the stylopharyngeal muscle and its variant.

Clinical Significance

The stylopharyngeus muscle forms a part of a significant anatomical structure known as stylopharyngeal septum (styloid diaphragm). While entering the pharyngeal spaces, this septum is considered to be an important surgical landmark.[5] The inferior border of this diaphragm divides the submandibular gland area in the anterior region and the carotid vessels in the posterior region. The superior border of this diaphragm divides the parotid gland area in the anterior region and the retrostyloid structures in the posterior region. Thus, this diaphragm acts as a hammock for the submandibular and the parotid glands.

Also, the stylopharyngeus septum divides the parapharyngeal space into two compartments (retrostyloid and prestyloid). The presence of any deep-lobe parotid tumors or any ectopic salivary gland tumors specifically occupies the prestyloid space. Their growth may displace other significant anatomic structures posteriorly. In such cases, stylopharyngeus muscle and the styloglossus muscle can be considered as the safe posterior boundary during dissection as they protect the significant anatomic structures of the retrostyloid space.[6][7]

During the surgery for neurogenic tumor of the cranial nerves, the superior control of the internal carotid artery can be achieved by dissecting the area present between the stylopharyngeus muscle and the styloglossus muscle.[7] Along with the other longitudinal pharyngeal muscles (palatopharyngeus, and salpingopharyngeus), the stylopharyngeus muscle causes pharyngeal shortening and plays an important role in pharyngeal clearance. This avoids postdeglutitive overflow aspiration.[8][9] The contraction of the stylopharyngeus muscle flattens the piriform recess. Thus, helping in the clearance of the piriform recess.

Glossopharyngeal nerve anesthesia bilaterally produces a dysfunction of the stylopharyngeus muscle resulting in the collapse of the dorsal wall of the nasopharynx.

Occasionally, the stylopharyngeus muscle may compress the cervical part of the internal carotid artery. The patient may mimic symptoms of Eagle syndrome, which is usually due to an elongated styloid process. In such cases, routine radiographs would not be useful in symptomatic patients as the styloid process would appear to be normal. The compression may only be visible on CT angiography or conventional angiography. The level of compression is usually medial and distal to the styloid process. It may occur only with head rotation.[10]

Other Issues

The posture of the head influences the contraction of the stylopharyngeus muscle affecting pharyngeal clearance. A chin-down position renders pharyngeal clearance by the stylopharyngeal muscle relatively ineffective.[3]