Continuing Education Activity

Septic arthritis of the sternoclavicular joint is rare and represents less than 1% of all bone and joint infections. A sternoclavicular joint infection is, in the majority of cases, associated with other systemic illnesses and/or general poor health status. This activity should help enhance the readers understanding of sternoclavicular joint infections. It should also help the interprofessional team better understand the workup and diagnostic approach to the suspected infected sternoclavicular joint. Furthermore, this activity can serve as a guide for providing care to the patient with a painful sternoclavicular joint and suspected infection.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of sternoclavicular joint infections.

- Explain the usual history and physical examination findings of sternoclavicular joint infections.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for sternoclavicular joint infections.

- Describe some interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance upper extremity care and improve long term outcomes.

Introduction

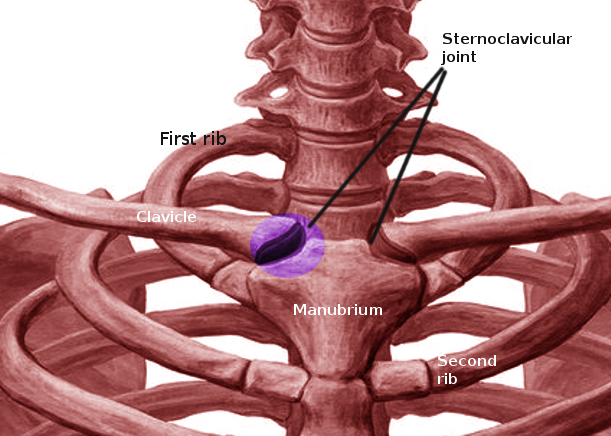

The sternoclavicular joint is a saddle-shaped diarthrodial joint that joins the upper extremity appendicular skeleton to the axial skeleton. The large medial clavicle articulates with the superomedial manubrium and costal cartilage of the first rib, forming a joint with very little bony stability.[1] Within the joint is an intra-articular disc ligament composed of dense fibrous cartilage that provides structural support and prevents medial displacement of the clavicle.[2] The surrounding robust costoclavicular ligament and capsule offers an added layer of support.[2] The primary restraints to anterior and posterior translation of the joint are the anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments.[3] Despite these restrictions, the sternoclavicular joint is actually very mobile and moves more than 30 degrees in the axial and coronal planes while having more than 45 degrees of rotation.[4] Functionally, it is quite similar to other amphiarthroses, such as the sacroiliac joint or pubic symphysis.[5]

Blood supply to the joint comes from the articular branches of the suprascapular and internal thoracic arteries.[1] The nerve to the subclavius muscle and the medial suprascapular nerves provide innervation to the sternoclavicular joint.[1]

Septic arthritis of the sternoclavicular joint is rare and represents less than 1% of all bone and joint infections.[5][6] A sternoclavicular joint infection is, in the majority of cases, associated with other systemic illnesses and/or general poor health status. Common concurrent issues include diabetes, intravenous drug use, immunosuppression, and rheumatoid arthritis.[7] While rare, prompt diagnosis and treatment are essential to prevent spread into the posteriorly located great vessels, mediastinum, and pleural space.[7]

Etiology

Ross et al. reviewed 180 cases of sternoclavicular joint septic arthritis and found that the most common offending bacteria were Staphylococcus aureus (49%), followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (10%) and Brucella melitensis (7%).[5] In a similarly designed study, Brancos et al. reported on sternoclavicular joint infections in a population of heroin addicts. They confirmed S. aureus and P. aeruginosa as the most common isolates.[8] In 2015, Jain et al. described tuberculosis (TB) as an unusual cause of sternoclavicular septic arthritis. They reported a small series of 9 men and 4 women who eventually received a diagnosis of sternoclavicular septic arthritis secondary to TB.[9]

Epidemiology

In the general population, sternoclavicular septic arthritis accounts for less than 1% of bone and joint infections.[6] Interestingly, it accounts for 17% of septic arthritis cases amongst intravenous drug users.[5] The classic involved patient demographic consists of males in the fourth to fifth decade of life. In the previously mentioned case series by Ross et al., 73% of sternoclavicular joint infections involved males with a mean age of 45.[5] Interestingly, no risk factor for infection was identifiable in almost a quarter of the patients in the study.[5] Von Glinski et al. reported 13 cases of sternoclavicular joint infection involving eight men with a mean age of 37 years.[10]

Pathophysiology

Infection of the sternoclavicular joint can occur via direct inoculation of the joint or contiguous spread from a nearby area; however, the most common pathway is hematogenous spread via the bloodstream. This particular mechanism explains why the prevalence of this rare condition is so much more commonly seen in patients with a history of intravenous drug abuse.[11]

A healthy patient may be able to contract a spontaneous sternoclavicular joint infection. Sanelli et al. describes a case of staphylococcal septic arthritis that is associated with no known predisposing risk factor. That patient was able to be managed with medical therapy alone.[12]

There have been reports of patients contracting sternoclavicular joint infections in association with dialysis. Renoult et al. first reported on the association of hemodialysis and sternoclavicular joint infection. They reported on two patients who were able to be treated non-operatively after addressing the condition.[13] Renal failure may further immunosuppress and predispose such patients to a sternoclavicular joint infection.

History and Physical

An extensive history involving the assessment of systemic symptoms is vital as many of the conditions that affect the sternoclavicular joint are systemic. The clinician should question the patient regarding a family history of sternoclavicular arthritis, intravenous drug use, and systemic complaints such as subjective fevers, chills, night sweats, and malaise. Pain localized to the sternoclavicular joint or medial clavicle is a high-risk patient, or an individual with systemic symptoms should raise suspicion for infection.

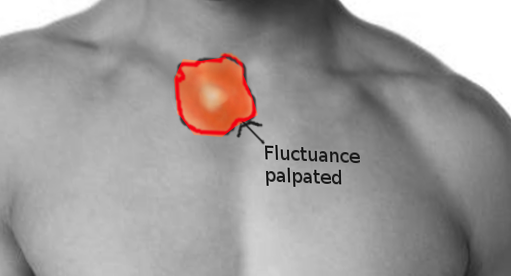

An infected sternoclavicular joint is likely to be swollen, warm, tender, and erythematous on physical examination. Patients are painful both with direct palpation of the joint as well as passive/active range of motion of the ipsilateral shoulder. Typically, sternoclavicular joint septic arthritis is a unilateral condition, while inflammatory arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis affects both joints simultaneously. One should pay attention to any fluctuance, joint translation, joint asymmetry, and bony enlargement. Joint asymmetry should raise concern for a sternoclavicular joint dislocation, which may represent a surgical emergency if directed posteriorly with neurovascular changes.[14]

Evaluation

As in most cases of orthopedic infections, an elevated white blood cell count (WBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) present as elevated. These markers are relatively nonspecific and may increase in cases of gout, systemic illness, or infection of another joint. As previously stated, these patients may be immunosuppressed and may be unable to elicit a systemic response that produces impressive inflammatory labs. It is also reasonable to routinely obtain blood cultures on these patients at the time of presentation, as estimates are that nearly two-thirds of patients with sternoclavicular joint infections are systemically septic.[5]

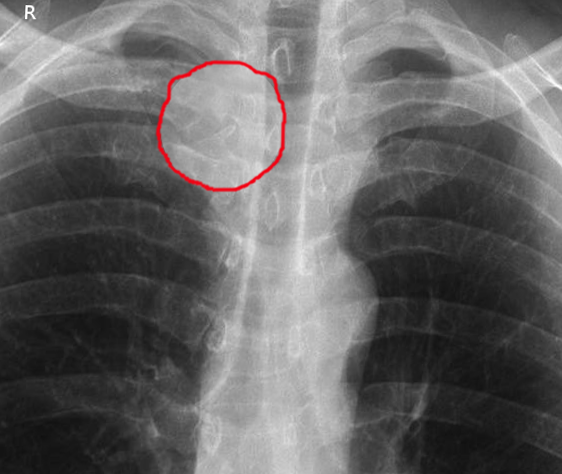

Imaging studies for these patients are, unfortunately, nonspecific and are most helpful in ruling out other painful etiologies. If deemed necessary, an MRI is an excellent tool to evaluate for joint effusion, nearby abscess, or early osteomyelitis.[5] Radiographs of the sternoclavicular joint may be helpful but likely only in the setting of osteomyelitis as isolated septic arthritis would lack bony involvement by definition. Von Glinski et al. obtained chest radiographs in all patients in their series of 13 to assess surrounding tissues.[10]

CT scan may hold some additional value as it may show earlier bony changes as well as demonstrate the presence of any peri-articular or retrosternal abscess. Von Glinski et al. described a series of 13 patients, of whom 10 had a periarticular abscess that was identifiable on a preoperative CT scan.[10]

The gold standard for diagnosing sternoclavicular joint septic arthritis remains arthrocentesis. Aspirated joint fluid should undergo evaluation for crystals, cell count, percentage of neutrophils, and the presence of bacteria using gram stain and culture. A total nucleated cell count greater than 50000 with over 90% neutrophils with no crystals is concerning for infection. A positive gram stain or culture is virtually diagnostic regardless of the other synovial fluid analyses.

Rochuae et al. reported on a group of sternoclavicular joint arthritis patients and found that only 53% had proven bacteremia at the time of evaluation.[15] Blood cultures are a reasonable adjunct to obtain during patient evaluation. However, this relatively low positivity rate means blood cultures cannot be solely relied upon to isolate the offending organism.

Treatment / Management

While there are reports of successful treatment with needle arthrocentesis and antibiotics, the mainstay of treatment for sternoclavicular joint infections is surgical irrigation and debridement with tailored intravenous antibiotic therapy.[9][16] Care should be taken to evaluate the surrounding chest wall for loculated abscesses that may be a source of continued infection at the time of operative irrigation and debridement. Particular aggressive organisms or recalcitrant infections may require resection of the medial clavicle with possible soft tissue coverage given the subcutaneous nature of the sternoclavicular joint. When resecting the medial clavicle, the vital retrosternal structures, as well as the surrounding ligamentous structures, must be protected.[1] If the supporting ligamentous structures are damaged, pain and instability can result.[17]

In a series of 10 patients who underwent resection arthroplasty for sternoclavicular joint septic arthritis, Chun et al. reported good functional results with intramedullary ligament reconstruction and 4 to 8 weeks of intravenous antibiotics.[18] There are multiple studies available in the literature detailing joint resection techniques as well as closure methods.[9][19][18] Whitlark et al. describe a single-stage washout with implantation of antibiotic laden beads and a good outcome in a single case.[20]

Less invasive management may be an option in less advanced disease or an immunocompetent host. Multiple authors have reported on cases or case series that were manageable with antibiotics alone.[13][12] However, due to a lack of larger studies with longer follow up, the success rate of this treatment technique is not well described. Isolated aspiration or needle lavage has also been suggested but lacks significant literature to prove its reliability.

If there becomes a significant soft tissue defect from adequate debridement, additional flap coverage may be required. Although uncommon, it is possible to need a soft tissue transfer. Opoku-Agyeman et al. reported on several surgical configurations for pectoralis major flaps in the reconstruction of sternoclavicular defects.[21] These techniques include a pectoralis split and advance, split and rotate, or entire pectoralis harvest and transfer. These techniques may be considered in surgical planning if significant debridement is required. Primary muscle flap closure has demonstrated excellent outcomes in a series of 40 patients, as described by Kachala et al.[19]

A multidisciplinary approach, including the involvement of infectious disease, may optimize the patient outcome. Postoperatively, or in the case of medical management, the mainstays of antibiotic therapy for any septic arthritis should be a post-operative course of antibiotics of at least two weeks depending on the offending agent and the recommendations of your infectious disease team.[22]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of sternoclavicular joint infection includes sternoclavicular joint arthritis, clavicular osteomyelitis, clavicular fracture, sternal fracture, pleuritis, gout, dislocation, condensing osteitis of the clavicle, mediastinitis, or rib fracture.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with sternoclavicular joint infections recognized promptly and treated appropriately is excellent. Burkhart et al. reported a case series of sternoclavicular joint infections treated with joint resection with no resulting limitations of the affected upper extremity.[23] Untreated infections can develop into extrapleural or intrathoracic abscesses and quickly become life-threatening if the retrosternal structures are involved.[1]

Initial post-operative care will revolve around clearing the infection and obtaining adequate soft tissue healing. After achieving source control, the function of the limb is the primary focus. In an excellent review of sternoclavicular joint instability, Sewell et al. describe physical therapy as being beneficial for patients with SC joint instability.[24] Being able to offer treatment as a postoperative adjunct for a patient experiencing slow recovery may increase patient rehabilitation and improve the overall outcome.

Complications

Complications include: the need for repeat surgery, osteomyelitis, skin loss over the affected area requiring flap coverage, instability of the joint, need for joint reconstruction, inability to clear the infection, and progression to the chest wall or mediastinal involvement. In addition, patients may have chronic pain with shoulder range of motion or pain with heavy lifting in cases of chronic infections or delayed diagnoses.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Correcting modifiable risk factors and providing education regarding the dangers of intravenous drug use may lower the incidence of sternoclavicular joint infections.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of patients with sternoclavicular joint infection are complex and best done with an interprofessional team. The nurses may be the first to identify the pathology in in-patients, especially in those with central catheters. Outpatients usually present to the emergency room.

A combination of history, physical examination, and laboratory findings is necessary to diagnose sternoclavicular joint infection. Many of these patients likely present to primary care providers or emergency departments, so a basic knowledge of this condition is required to make a prompt diagnosis and avoid the spread of the infection or a poor outcome. The services of radiology are vital as imaging is often used to confirm the diagnosis. The infectious disease expert should be consulted for antibiotics and the duration of therapy. A surgeon is usually involved, as many patients require drainage and debridement. The board-certified infectious disease pharmacist should pay attention to culture results and ensure that the patient is on the appropriate antibiotics compared to antibiogram data. The pharmacist can also verify dosing and duration and check for potential drug interaction, informing the team if there are any issues. Nursing can assist the clinician during the case, verifying patient compliance, acting as a bridge to the clinician for the patient and other providers (e.g., physical therapist), and providing patient counsel.

Prompt referral to an orthopedic or thoracic surgeon is vital if the infection has resulted in osteomyelitis of the sternum or clavicle. Orthopedic and thoracic surgeons must provide education on the ramifications of a missed diagnosis to other healthcare providers. Close communication between the team members is vital for improving outcomes. [Level 5]