Introduction

The metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint of the thumb plays an important role in normal hand gripping and pinching. The radial and ulnar collateral ligaments (UCL) are the primary stabilizers to varus and valgus stress on this joint. From the functional point of view, the UCL is of greater importance because it resists radially directed forces during forceful grasping. The term “gamekeeper’s thumb” was first coined in 1955 by Campbell who identified the UCL injuries as an occupational disease in Scottish gamekeepers. The gamekeepers sacrificed the rabbit by strangling the animals with their thumb and index finger, and the repeated valgus stresses resulted in UCL injury and chronic instability of the MCP joint. In the present day, this lesion occurs more frequently in acute sports-related injuries.[1]

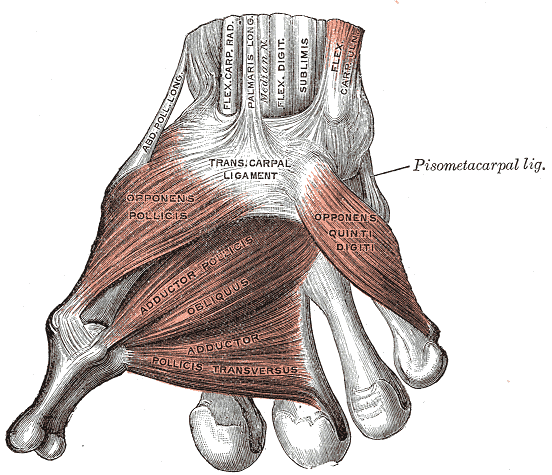

The UCL is composed of a proper collateral ligament (PCL) and an accessory collateral ligament (ACL). The PCL originates from the dorsal third of the metacarpal head and inserts on the volar aspect of the proximal phalanx. The ACL originates palmar to the PCL and runs continuously with the PCL to insert on the volar plate. The PCL is taut in flexion, while the ACL is taut in extension. Both ligaments ensure the ulnar stability of the MCP joint. The Adductor pollicis inserts on the proximal phalanx, functioning as a dynamic stabilizer of the MCP joint. It lies superficial to the UCL. Understanding the structural relationship between the adductor pollicis aponeurosis and the UCL is crucial to understand the pathoanatomy of the "Stener lesion."[2]

Etiology

The UCL measures 12-14 mm X 5-8 mm and originates from the head of the metacarpal. It inserts into the medial aspect and base of the proximal phalanx of the thumb. When the UCL is stressed, it can avulse the bone fragment at the insertion site- leading to the gamekeeper's thumb.

Injuries to the UCL are caused either by chronic repetitive valgus stresses, such as originally described in gamekeepers or by an acute hyperabduction trauma. Common causes include skiing injuries when the skiers fall on the abducted thumb with the ski pole in hand (skier’s thumb), or injuries in other sports such as hockey, soccer, handball, basketball, and volleyball.[2]

The one disorder associated with the gamekeeper's thumb is rheumatoid arthritis.

Epidemiology

The estimated incidence in the United States is approximately 200,000 patients per year. It is related to 86% of all injuries to the base of the thumb.

Pathophysiology

The UCL injuries can be categorized into 3 grades. A grade I injury refers to a stretched but still intact ligament. A grade II injury refers to a partial thickness tear of the ligament. A grade III injury refers to a complete rupture of the ligament. Most UCL injuries occur at the distal attachment on the proximal phalanx, and associated bony avulsion fractures are seen in 20% to 30% of UCL ruptures. When a grade III sprain occurs, the strong stress force may lead to a retracted proximal end of the UCL, lying superficial to the adductor pollicis aponeurosis. The interposition of the aponeurosis between the ruptured UCL and the proximal phalanx hampers reduction and healing of the torn ligament. This displaced tear, namely the Stener lesion, occurs in 64% to 87% of all grade III injuries.

History and Physical

The patient usually describes a specific eliciting event causing a combination of hyperextension and radial deviation to the thumb. Almost any type of valgus stress to the thumb can result in stress on the UCL.

In acute injuries, swelling, bruise, and local tenderness may be presented on examination. It is vital to examine the other normal thumb first and assess the range of motion and valgus stability; only then should the injured thumb be examined.

A mass lesion palpated proximal to the MCP joint may suggest a Stener lesion. The UCL integrity is evaluated by a stress test that applies radial stress on the proximal phalanx with the MCP joint in full extension and 30 degrees of flexion, to evaluate the ACL and the PCL respectively. Sometimes the lesion is too painful to perform the stress test in acute injuries, and local anesthetic injection can improve patient cooperation. The examiner assesses both the endpoint and the metacarpal-phalangeal deviation. The absence of a firm endpoint in the stress test indicates a UCL complete tear. A resultant metacarpal-phalangeal deviation more than 35 degrees on the affected side or a difference more than 15 degrees between the affected side and the normal side is also indicative of a complete UCL tear. The physical examination can differentiate a partial or a complete tear, but the determination of a Stener lesion requires further imaging evaluation because the physical finding of a palpable mass at the tender site is not pathognomonic.[2][1]

Evaluation

In all cases, an x-ray should be obtained before a physical exam to exclude metacarpal fractures.

The plain radiograph is the first-line imaging tool to evaluate the associated fracture and MCP joint subluxation. The avulsed bony fragment of the proximal phalanx in the plain radiograph usually indicates the distal end of the injured UCL. A displaced tear is diagnosed when the displacement of the bony fragment is more than 1 mm.

If the plain radiograph is normal, but there is a clinical suspicion of the gamekeeper's thumb, further imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or high-resolution ultrasound (US) can be performed. MRI is regarded as the gold standard to diagnose a UCL injury, with a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 95%, but has the disadvantage of high cost and less availability. The MRI can identify a partial/complete tear, bone edema, and associated fracture.

The US is a useful diagnostic tool for UCL injuries as it is cost-effective, widely available, and capable of real-time dynamic examination. On US examination, a partial tear is depicted as a general thickening of the UCL with hypoechoic change. In a non-displaced complete tear, a well-defined defect may be demonstrated, but the proximal and distal ends of the ligament remain in its anatomic positions. A displaced complete tear is typically seen as the so-called “yo-yo” sign, a hypoechoic mass proximal to the MCP joint line, which is corresponding to the retracted proximal end of the UCL. It is reported that the accuracy of US to diagnose a Stener lesion ranges from 81% to 100%, depending on the experience of the examiner.[3]

In some patients, stress testing may be required to confirm the diagnosis. This usually requires local anesthesia into the MCP joint and then performing the physical exam.

Treatment / Management

The key factor in deciding the treatment plan is whether the UCL injury is displaced or non-displaced. A displaced UCL complete tear cannot heal by itself and requires a surgical intervention to prevent permanent instability and degenerative changes of the MCP joint.

The repair should ideally be done within the first 21 days of the injury. Late repairs have been known to have marked pain and weakness on pinch grip. In addition, there is a risk for arthritis of the MCP joint. Surgery requires reducing the joint and using K-wire to maintain the joint in position. The UCL is repaired. The avulsed bone may be removed if small but if the fragment is large, it should be reduced and reattached with wire. Patients who have timely surgical repair have favorable outcomes. Patients with a delayed diagnosis have less favorable outcomes.

If the complete tear is treated conservatively, there is a 50% failure risk. Braces may be an option for patients who refuse surgery. A thumb spica splint can be used but obtaining complete stability is rare.

A non-displaced tear is immobilized with a protective splint for 4 to 6 weeks. The MCP joint is fixed, and the interphalangeal joint is free to move to prevent stiffness. Associated fractures, if not displaced, are also managed conservatively. Physical therapy can be applied to facilitate recovery.[4][5]

Differential Diagnosis

- Stener lesion

- Fracture of the phalanx

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Osteoarthritis

Complications

Complications related to surgery include the following:

Neuropraxia associated with stretching of the radial sensory nerve. The neuropraxia may last 6-12 months.

Post-surgical stiffness of the interphalangeal and MCP joint is a very common complication. Hence, rehabilitation is a must.

For those who do not seek timely treatment, chronic instability is common. The longer the delay for treatment, the less likely will the repair be successful. In addition, the dorsal capsule, extensor pollicis longus, and extensor pollicis brevis muscles will atrophy, which further adds to the instability of the joint. The patient will notice that the thumb rotates into supination and will be displaced volarly.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of game keeper's thumb is complex; it is also associated with high morbidity if not appropriately treated. The condition is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a hand surgeon, emergency department physician, orthopedic surgeon, orthopedic nurse, and physical therapist. Patients who ski and use the thumb frequently in certain occupations should be educated that if the thumb is injured, it is important to seek treatment early. If the UCL is torn is displaced, surgery is necessary. Unfortunately, even after surgery good outcomes are not assured. All patients need extensive rehabilitation. Recovery is often prolonged and chronic pain is common.