Introduction

The sigmoid colon is the terminal portion of the large intestine before reaching the rectum. It connects the descending colon with the rectum. The sigmoid colon derives its name from a Greek letter sigma. Its location is usually in the pelvis, but as it is a mobile structure with a mesentery, it can often become displaced into the abdominal cavity. The primary function of the sigmoid colon is the absorption of water, vitamins, and minerals from the undigested food particles, just like the preceding portions of the bowel; however, it does so to a lesser extent. The sigmoid colon is a hindgut structure and receives its blood supply, innervation, as well as its lymphatic drainage, similar to other hindgut structures. Various common and uncommon diseases can affect the sigmoid colon, many of which could require surgical correction if medical management fails.[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

Structure:

The average length of the sigmoid colon is 25 to 40 cm (10 to 15.75 in). The sigmoid colon is an “S” shaped portion of the large intestine that begins in front of the pelvic brim as a continuation of the descending colon and becomes the rectum at the level of the third sacral vertebrae. Unlike the descending colon, the peritoneum surrounds the sigmoid colon, and thus, it is not a retroperitoneal structure. The sigmoid mesocolon attaches the sigmoid colon to the posterior wall of the abdomen. At the level of S3, it again becomes a retroperitoneal structure.

Function:

The sigmoid colon receives stool that has had most of the nutrients and water reabsorbed from it at this point. Its primary purpose is to remove the final components such as water, vitamins, and minerals from the gut contents through reabsorption to make the stool solid enough to be stored in the rectum. The sigmoid colon then pushes the firm stool into the rectum through a functional rectosigmoid sphincter with the help of strong peristaltic contractions in preparation for fecal excretion, allowing for the storage and initiation of the defecation reflex.[4]

Embryology

Much like the rest of the colon, the sigmoid colon is derived from the three basic germinal layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) and develops as a hindgut structure relative to the blood supply and innervation. Histologically, the epithelial lining arises from endoderm with the smooth muscle components and connective tissue involved in the peristaltic contractions originating from the mesoderm layer. The final ectoderm layer gives rise to the serosal covering of the sigmoid colon as well as the neural crest cells, which develop into the enteric nervous system, giving rise to the autonomous control of the gastrointestinal tract. Additionally, this portion of the colon develops and is maintained as an intraperitoneal structure and marks the transition from the retroperitoneal descending colon and rectum.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood Supply:

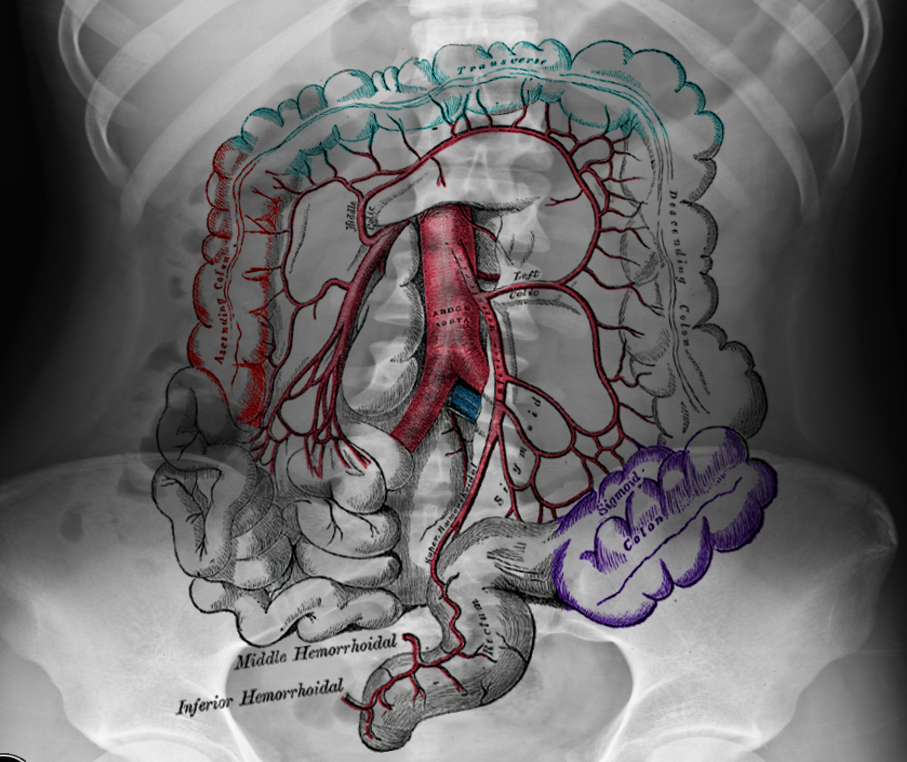

As the sigmoid colon develops as a hindgut structure, it receives its blood supply from the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) and in specific, the sigmoidal branches. Also, the sigmoid colon receives collateral blood flow superiorly from the left colic artery and inferiorly from the superior rectal arteries, both of which also originate from the IMA. The rectosigmoid junction is a major watershed zone known as Sudeck’s point, which is prone to ischemia in states of decreased perfusion. The arteries supplying this intraperitoneal organ traverse through the sigmoid mesocolon, which is a fold in the peritoneal lining of the abdominal cavity that tethers the colon to the posterior abdominal wall.

Lymphatic Drainage:

Lymphatic drainage for the sigmoid colon follows the path of the IMA and its bifurcating branches in a retrograde fashion, draining into lymph nodes located within the mesentery and eventually ending up in the preaortic inferior mesenteric nodes.[5][6]

Nerves

Gastrointestinal motility is under the control of through the enteric nervous system that develops as neural crest cells derived from the ectoderm germ layer migrate into the walls of the colon; this forms the myenteric or Auerbach plexus, which is between the circular and the longitudinal muscle layers, as well as the submucosal or Meissner plexus, which is located just beneath the intestinal mucosa. These nerves function independently from the central nervous system to control both motility and secretion. The enteric nervous system can fall under the influence of changes in sympathetic tone originating from the L1-L2 intermediolateral cell column of the spinal cord and parasympathetic tone from the S2-S4 pelvic splanchnic nerves.[5]

Muscles

The motility of the sigmoid colon, like the rest of the intestinal tract, relies on two layers of smooth muscle located within the wall of the structure. These layers consist of an inner circular layer of muscle tissue and an outer longitudinal layer. The longitudinal muscles form three bands of muscle that are visible on external examination of the colon known as taenia coli. These bands are seen throughout the sigmoid colon and terminate at the rectosigmoid junction, marking the transition from the proximal sigmoid colon to the distal rectum. These layers of smooth muscle are derived from the mesodermal germ layer and function in the breakdown, compaction, and propulsion of stool as it moves towards the rectum for eventual excretion.[5]

Physiologic Variants

The average length of the sigmoid colon measures between 25 and 40 cm (10 to 15.75 in). A physiological variant has been seen in which an individual develops a redundant loop of the sigmoid colon. The redundant loop is when the sigmoid colon measures more than 40 cm long or by appearing to be longer than what the person’s abdomen can accommodate. This redundant bowel can create a spectrum of clinical symptoms ranging from severe bowel and bladder dysfunction to no symptoms at all.[7]

Surgical Considerations

In the case of recurrent diverticulitis or volvulus, as well as for suspicious sigmoidal malignancy, the surgeon can perform a sigmoid hemicolectomy through the ligation of the associated vessels, resection of the diseased colon, and the creation of a colostomy or anastomosis between the descending colon and the rectum.[8]

Clinical Significance

Hirschprung's Disease:

Hirschsprung’s Disease or aganglionosis of the sigmoid colon is a disease that affects the contractile function of the caudal sigmoid colon. In this disease, neural crest cells fail to migrate properly to the distal colon. This failure of migration leads to disruption of the enteric nervous system and thus motility and function of the sigmoid colon. This anomaly is seen classically in newborns when they are unable to pass their first stool (meconium). This disease appears in nearly 5% of children born with Down syndrome, and research shows that mutations in both germline and somatic cells contribute to the pathogenesis.[9]

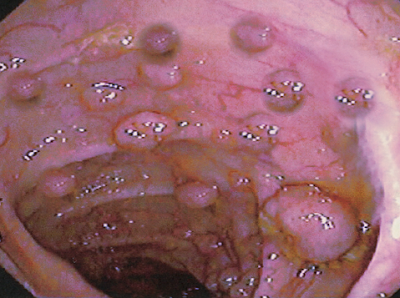

Diverticulitis:

Diverticulitis is a common disease of the sigmoid colon in which small diverticula or outpouchings of weakened bowel wall become inflamed. These outpouchings are false diverticula only containing the mucosa and submucosal layers. Diverticula form in the areas where blood vessels penetrate the bowel wall to supply the mucosa. These areas of bowel wall weakness can become inflamed and lead to abscess development, fistulas, or perforations leading to intense pain localized to the lower left abdominal quadrant due to peritoneal irritation. This condition's pathogenesis is multifactorial and is influenced by genetics, diet, activity levels, and fiber intake.[10]

Volvulus:

Sigmoid volvulus is a disease that develops when the colon twists around its mesocolon; this occurs in the region of the sigmoid colon due to the morphological "S" shape of the colon and the high amounts of pressure that can form as the stool is compacted and prepared for excretion. When this occurs, the blood vessels that reside within the mesentery can become occluded and lead to ischemia of the bowel. Also, the twisting of the bowel creates a distal obstruction inhibiting the movement of stool into the rectum. This typically will present in people with redundant bowel, as well as those that are sedentary and prone to constipation. The physical exam will show a distended, and tympanic abdomen, and imaging will reveal large amounts of distended bowel, often referred to as the “coffee bean sign”.[11]

Colon Cancer:

Neoplasms can arise within the sigmoid colon and typically will present with changes in bowel habits such as decreased stool caliber and hematochezia. Colon cancers tend to metastasize to the liver through portal drainage and, eventually, the lungs via the inferior vena cava.[8]