Continuing Education Activity

The glenohumeral joint of the shoulder is the most commonly dislocated joint in the body and accounts for approximately 50% of all major dislocations seen in the emergency department. Most shoulder dislocations are anterior, and inferior shoulder dislocations occur are much lower frequencies. Inferior dislocations are generally not difficult to diagnose as the classic presentation is not subtle and can often be made from the doorway of an exam room. This activity describes the pathophysiology, evaluation, and management of inferior shoulder dislocations and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of inferior shoulder dislocations.

- Describe the presentation of a patient with an inferior shoulder dislocation.

- List the treatment and management options available for inferior shoulder dislocations.

- Explain the importance of enhancing care coordination amongst interprofessional team members to optimize outcomes for patients with inferior shoulder dislocations.

Introduction

The glenohumeral joint of the shoulder is the most commonly dislocated joint in the body and accounts for approximately 50% of all major dislocations seen in the emergency department. While anterior dislocations are very common and frequently seen in presentation, inferior shoulder dislocations have an incidence of about 1 in 200 (0.5%) of all dislocations. This is not subtle, and diagnosis usually can be made from the doorway of an exam room.[1][2][3]

Etiology

This type of dislocation is commonly referred to as luxatio erecta which means "erect dislocation" in Latin. This name derives from the typical way in which the arm is usually fully abducted and held above the head on presentation. [4][5][6]

The majority are traumatic such as when the rider falls and tumbles off a motorbike. The humerus neck is pushed against the acromion and there is usually inferior capsule tears. Soft tissue injury or fractures are common with inferior shoulder dislocation. In addition, neurovascular injury, including axillary nerve damage are not uncommon with these dislocations.

Epidemiology

Although it accounts for less that one percent of all shoulder dislocations, when luxatio erecta occurs, it is much more frequent in men than in women with a reported ratio of approximately 10:1.

Pathophysiology

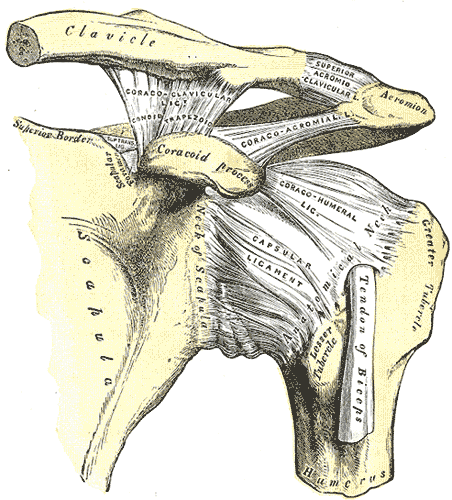

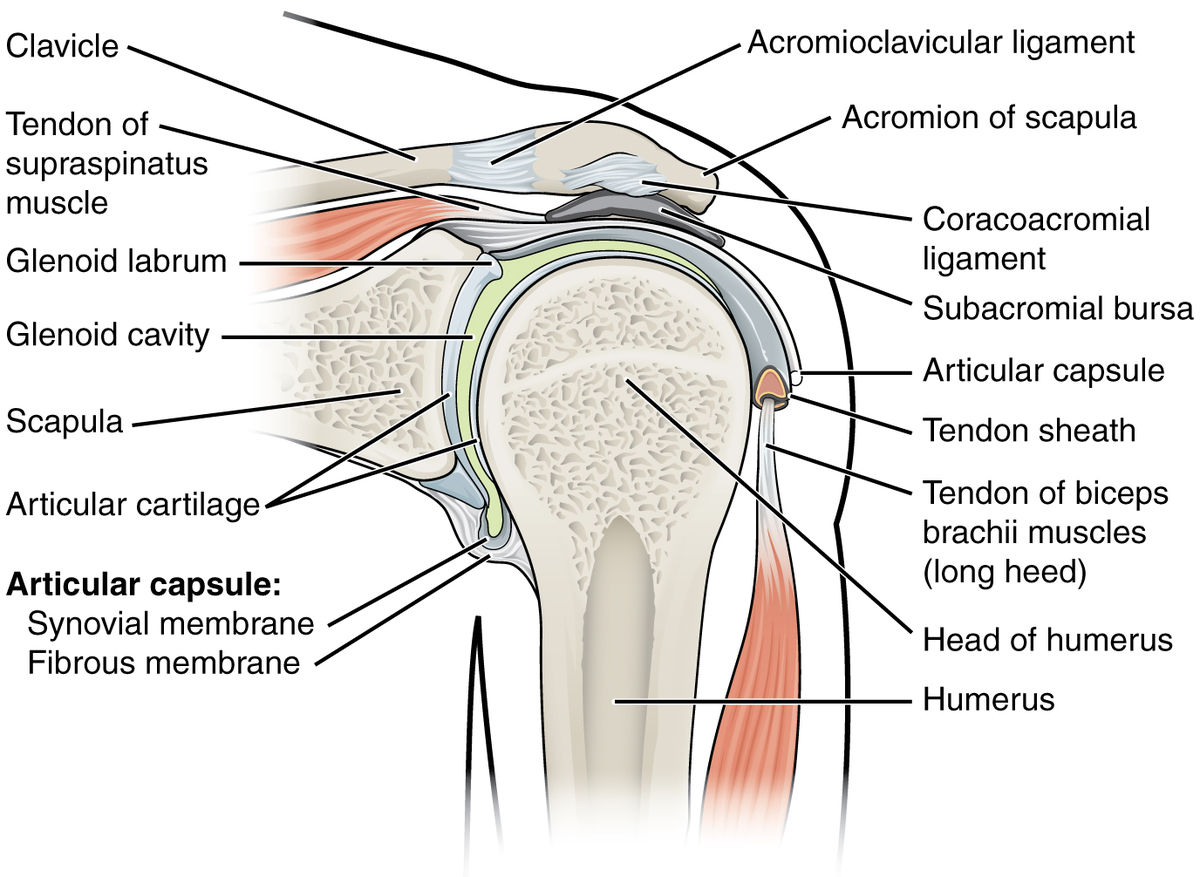

The upper extremity articulates with the axial skeleton through the joints of the shoulder girdle which includes the glenohumeral joint. The glenohumeral joint is a ball-and-socket joint that has the largest range of motion of any joint in the body. The glenoid fossa is about 1/3 the size of the humeral head articular surface and is extremely shallow, allowing for extraordinary mobility of the humeral head. A cartilaginous labrum along with muscular and tendinous attachments of the rotator cuff add to the stability of the joint, but given the above factors, dislocation is still a commonly encountered problem. Inferior dislocations frequently occur in patients who fall and grasp for an object overhead, hyperabducting the humeral neck against the acromion which forces the humeral head out of the socket, tearing the inferior capsule. This is typically associated with a serious injury to the shoulder complex. Also, high force trauma to the shoulder, such as that seen in motor vehicle crashes and falls from heights, also can result in dislocation, fracture, and other serious soft tissue and traumatic injuries. [7][8]

History and Physical

A patient who has suffered an inferior dislocation usually will present with severe pain and the evaluation begins with a good history and physical exam. Details of the mechanism of injury may be important to determine other injuries to the soft tissues surrounding the shoulder. If the injury occurred in a high force trauma, you will want to evaluate for other traumatic injuries. If the injuries occurred through a simple fall while the arm was abducted, there is a potential injury to the inferior capsule of the joint. MRI post-injury commonly has revealed rotator cuff injuries, glenoid labrum injuries, bone bruises, and impaction fractures of the superolateral aspect of the humeral head.

An inspection usually will reveal the classic appearance of the arm being fully abducted above the head with the elbow flexed at a 90-degree angle. You will want to assess for any distal neurovascular injuries, including assessment of the axillary nerve along with the radial and ulnar distributions of the brachial plexus, as these tend to occur in inferior dislocations. The patient will not be able to adduct the arm without significant pain, if at all. The examiner may be able to palpate the humeral head in the axilla or on the lateral chest wall. Keep in mind that a high index of suspicion must be maintained for other serious traumatic injuries to the thorax or abdomen if the dislocation involved high forces.

Evaluation

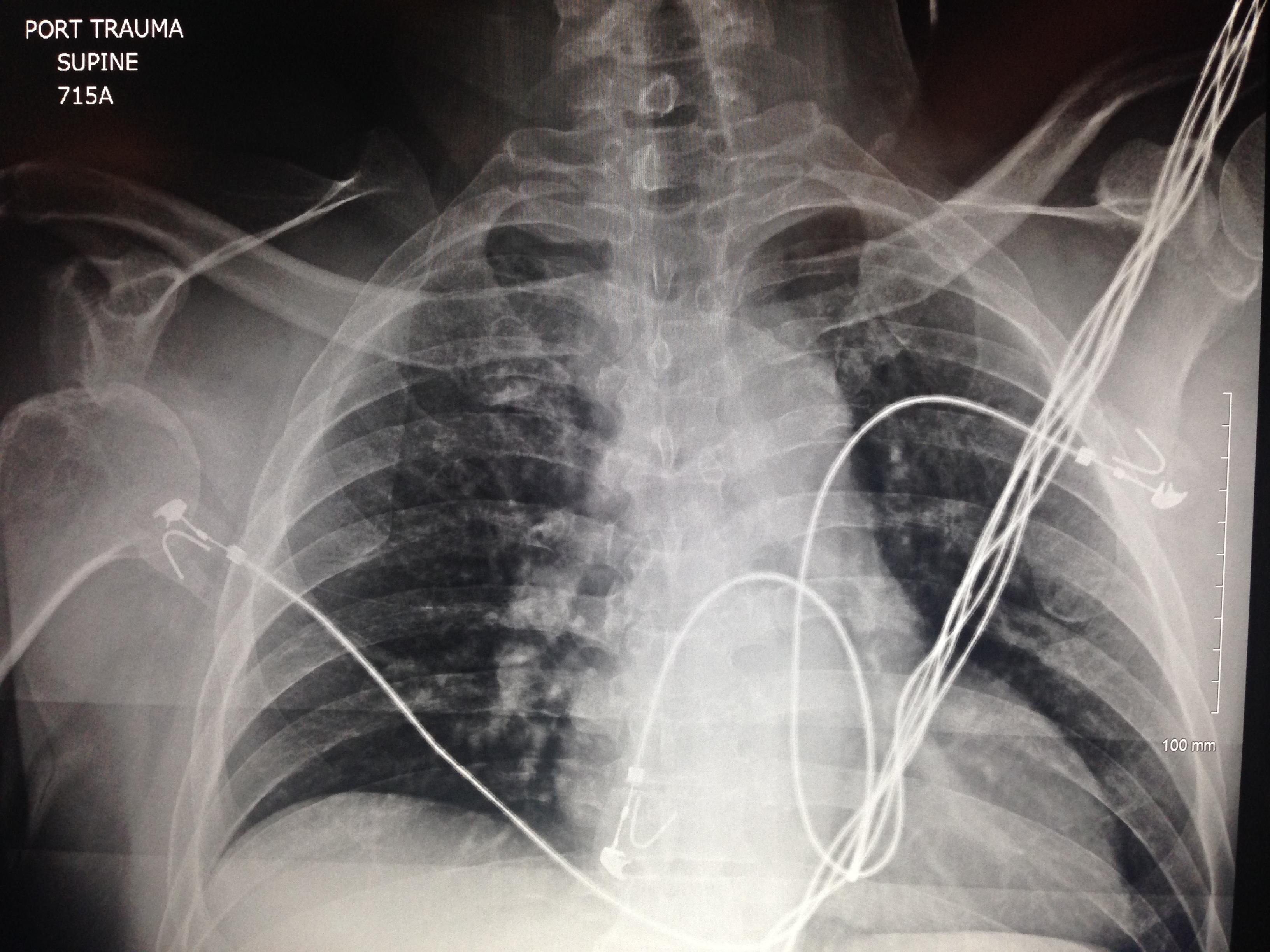

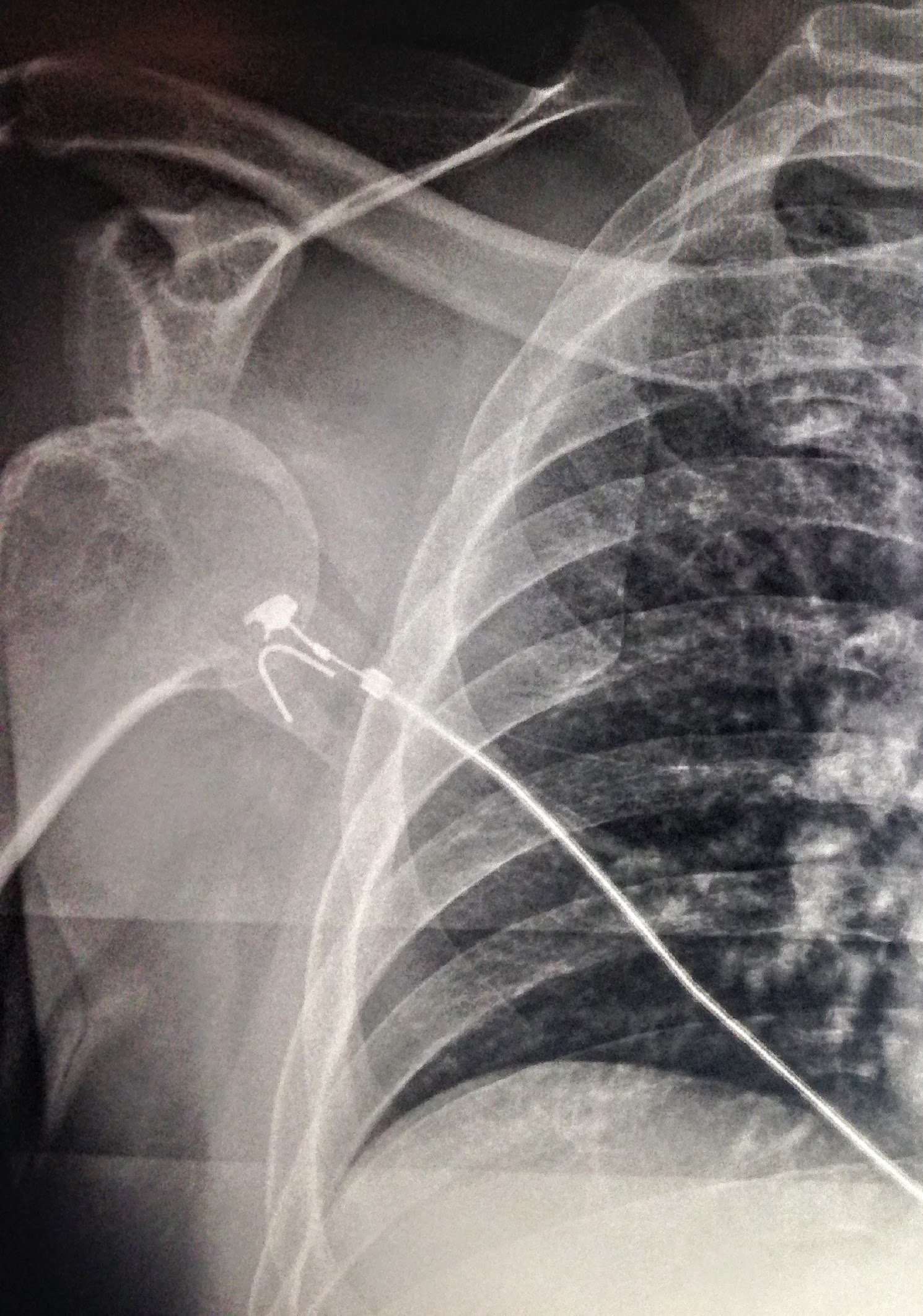

The diagnosis is confirmed with standard radiographs of the shoulder. Pre- and post-procedure anterior-posterior (AP) and scapular "Y" view radiographs should be obtained. Axillary views, while helpful in anterior and posterior dislocations, will not show the humeral head to glenoid relationship; an overlapping of those structures would be evident if that view is obtained. Inferior dislocation can be associated with concomitant fractures and physical exam alone is unable to differentiate this. Typically, films will show the superior articular surface of the humeral head inferior to the glenoid fossa. On Scapular "Y" view the head of the humerus will be sitting inferior to the normal expected position in the center of the glenoid, represented by the "Y" of the scapula.

If neurovascular injury is suspected, angiography or Doppler studies should be done. EMG may be used to assess nerve injury. MRI is frequently used to evaluate the extent of soft tissue injury.

Treatment / Management

Treatment will usually require procedural sedation to get adequate muscle relaxation and facilitate a closed reduction via traction-counter-traction. In some cases, a "buttonhole" deformity exists (humeral head is trapped in a tear of the inferior capsule), in which case open reduction is required. To reduce an inferior shoulder dislocation, extend the arm at the elbow and then apply overhead traction in the longitudinal direction of the humerus, an assistant may also apply cephalad pressure over the humeral head to help guide it into the joint. If needed, counter-traction can be applied toward the patient's feet by wrapping a sheet over the shoulder allowing the force to be applied in the opposite direction.

After reduction, bring the abducted arm into adduction against the body while supinating the forearm. Alternatively, a two-step closed reduction technique can be utilized. Here, the inferior dislocation is first converted into an anterior dislocation before being reduced. One hand is on the shaft of the dislocated humerus and the other hand on the medial condyle. An anteriorly directed force on the shaft rotates the humeral head from an inferior to an anterior position. The humerus is then adducted and any of the common anterior reduction techniques can be used (e.g. traction-counter-traction, Stimson, Cunningham, etc.) to reduce the head of the humerus into the glenoid fossa. The advantages of the two-step maneuver are that it requires a single operator, fewer attempts, minimal force, and only local analgesia or minimal procedural sedation. Often a "clunk" is felt or heard as the humeral head returns to its normal anatomic position and the range-of-motion will once again be free allowing the arm to be adducted and the forearm supinated.

Once back into anatomical position the arm should be placed in a shoulder immobilizer to avoid recurring dislocation as the soft tissue and muscle stabilizers are injured and will be lax. After reduction is achieved another thorough neurovascular exam should be performed, most neuropraxia will resolve after reduction. Post-reduction x-rays are also usually done to confirm reduction and check for any procedural injuries. In rare cases, closed reduction is not possible (i.e. the "buttonhole deformity" discussed earlier) and an operative reduction must be performed. Indications for surgery include irreducible dislocation by closed techniques, open dislocation, and vascular injury.

Differential Diagnosis

- Clavicular fracture

- Frozen shoulder

- Fracture of the humerus

- Rotator cuff tear

Prognosis

The majority of individuals who suffer inferior shoulder dislocation are young. A significant number of them will suffer a recurrent dislocation in the future. Rotator cuff tear is often the key pathology. Minor trauma accounts for the majority of recurrent dislocations. Some patients with pain may not be able to return to sporting activities and others may have restricted arm and shoulder use for 2-6 weeks. Recurrence rates among athletes vary from 30-90%.

Complications

- Fracture

- Neurovascular injury

- Frozen shoulder

- Soft tissue injury

Pearls and Other Issues

Inferior shoulder dislocation injuries when due to a traumatic mechanism are almost always accompanied by moderate to severe soft tissue injury, proximal humerus fractures, avulsion fractures of the greater tuberosity, fractures of the acromion, clavicle, coracoid process, or glenoid rim, and rotator cuff tears. Rotator cuff and greater tuberosity fractures can occur in approximately 80% of patients. Neurovascular compromise may affect the axillary nerve and brachial plexus. About 60% of patients have neurologic dysfunction, with the axillary nerve most commonly injured. Arterial injury occurs in three percent of patients that presents with absent radial pulses. Neurologic dysfunction typically resolves with shoulder reduction as the brachial plexopathy is also reduced. Adhesive capsulitis and recurrent dislocations are known long term complications of all shoulder dislocations. Despite the associated injuries, in a case series of 11 patients all were treated with closed reduction techniques and no one had persistent instability at follow up.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An inferior shoulder dislocation is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes the orthopedic nurses and therapists. While the diagnosis of an inferior shoulder dislocation is relatively simple, clinicians should assess for any distal neurovascular injuries, including assessment of the axillary nerve along with the radial and ulnar distributions of the brachial plexus, as these tend to occur in inferior dislocations. The patient will not be able to adduct the arm without significant pain, if at all. The examiner may be able to palpate the humeral head in the axilla or on the lateral chest wall. Keep in mind that a high index of suspicion must be maintained for other serious traumatic injuries to the thorax or abdomen if the dislocation involved high forces. To ensure proper long term healing and to mitigate any associated disability, orthopedic referral should be recommended for all patients that have been dislocated and reduced. The outcomes in most patients are fair but recurrence is a common problem.