[1]

Morioka T, Shigeto H, Ishibashi H, Nishio S, Yamamoto T, Yoshiura T, Fukui M. Magnetic source imaging of the sensory cortex on the surface anatomy MR scanning. Neurological research. 1998 Apr:20(3):235-41

[PubMed PMID: 9583585]

[2]

Yin PY, Hao MZ, Liu XD, Cao CY, Niu CM, Lan N. Neural Correlation between Evoked Tactile Sensation and Central Activities in the Somatosensory Cortex. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual International Conference. 2018 Jul:2018():2296-2299. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2018.8512779. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30440865]

[3]

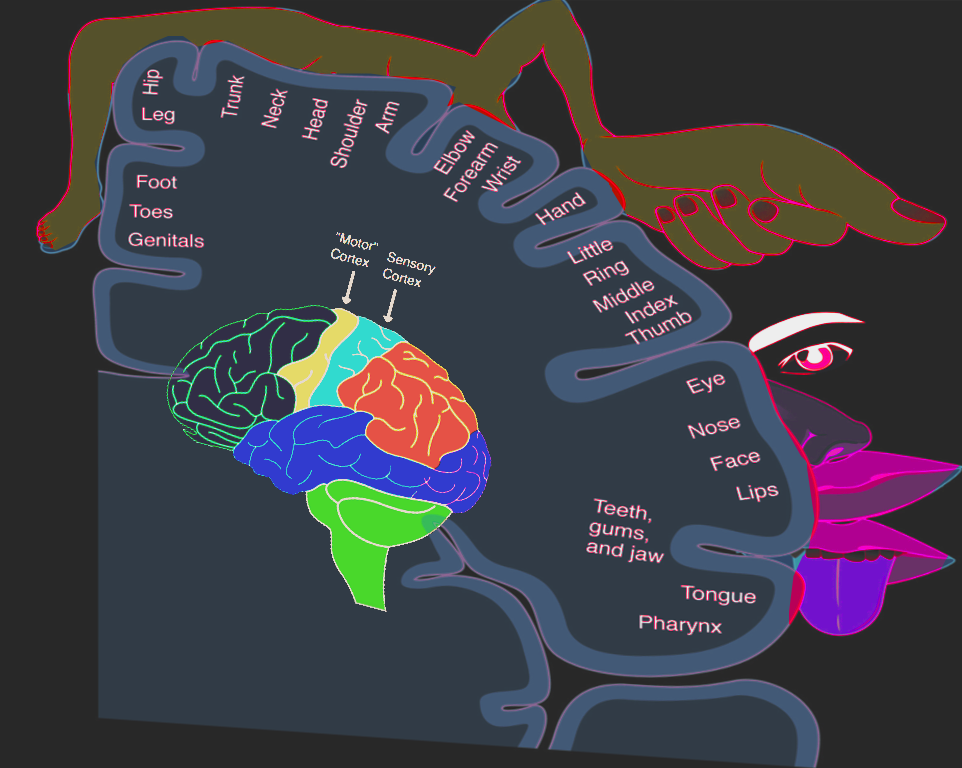

Gandhoke GS, Belykh E, Zhao X, Leblanc R, Preul MC. Edwin Boldrey and Wilder Penfield's Homunculus: A Life Given by Mrs. Cantlie (In and Out of Realism). World neurosurgery. 2019 Dec:132():377-388. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.08.116. Epub 2019 Aug 27

[PubMed PMID: 31470165]

[4]

Dall'Orso S, Steinweg J, Allievi AG, Edwards AD, Burdet E, Arichi T. Somatotopic Mapping of the Developing Sensorimotor Cortex in the Preterm Human Brain. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991). 2018 Jul 1:28(7):2507-2515. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhy050. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29901788]

[5]

Roux FE, Djidjeli I, Durand JB. Functional architecture of the somatosensory homunculus detected by electrostimulation. The Journal of physiology. 2018 Mar 1:596(5):941-956. doi: 10.1113/JP275243. Epub 2018 Jan 19

[PubMed PMID: 29285773]

[6]

Ha SK, Nair G, Absinta M, Luciano NJ, Reich DS. Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Histopathological Visualization of Human Dural Lymphatic Vessels. Bio-protocol. 2018 Apr 20:8(8):. pii: e2819. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2819. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29780855]

[7]

Jani RH, Sekula RF Jr. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Human Dural Meningeal Lymphatics. Neurosurgery. 2018 Jul 1:83(1):E10-E12. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyy171. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29917137]

[8]

Tamura R, Yoshida K, Toda M. Current understanding of lymphatic vessels in the central nervous system. Neurosurgical review. 2020 Aug:43(4):1055-1064. doi: 10.1007/s10143-019-01133-0. Epub 2019 Jun 18

[PubMed PMID: 31209659]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[10]

Al-Chalabi M, Reddy V, Alsalman I. Neuroanatomy, Posterior Column (Dorsal Column). StatPearls. 2023 Jan:():

[PubMed PMID: 29939665]

[11]

Navarro-Orozco D, Bollu PC. Neuroanatomy, Medial Lemniscus (Reils Band, Reils Ribbon). StatPearls. 2023 Jan:():

[PubMed PMID: 30252296]

[13]

Abdelrasoul AA, Elsebaie NA, Gamaleldin OA, Khalifa MH, Razek AAKA. Imaging of Brain Infarctions: Beyond the Usual Territories. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2019 May/Jun:43(3):443-451. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000865. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 31082950]

[14]

Shi J, Meng R, Konakondla S, Ding Y, Duan Y, Wu D, Wang B, Luo Y, Ji X. Cerebral watershed infarcts may be induced by hemodynamic changes in blood flow. Neurological research. 2017 Jun:39(6):538-544. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2017.1315499. Epub 2017 Apr 9

[PubMed PMID: 28393628]

[15]

Weill C, Suissa L, Darcourt J, Mahagne MH. The Pathophysiology of Watershed Infarction: A Three-Dimensional Time-of-Flight Magnetic Resonance Angiography Study. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association. 2017 Sep:26(9):1966-1973. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.06.016. Epub 2017 Jul 8

[PubMed PMID: 28694111]

[16]

Li Y, Li M, Zhang X, Yang S, Fan H, Qin W, Yang L, Yuan J, Hu W. Clinical features and the degree of cerebrovascular stenosis in different types and subtypes of cerebral watershed infarction. BMC neurology. 2017 Aug 29:17(1):166. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0947-6. Epub 2017 Aug 29

[PubMed PMID: 28851301]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence