Introduction

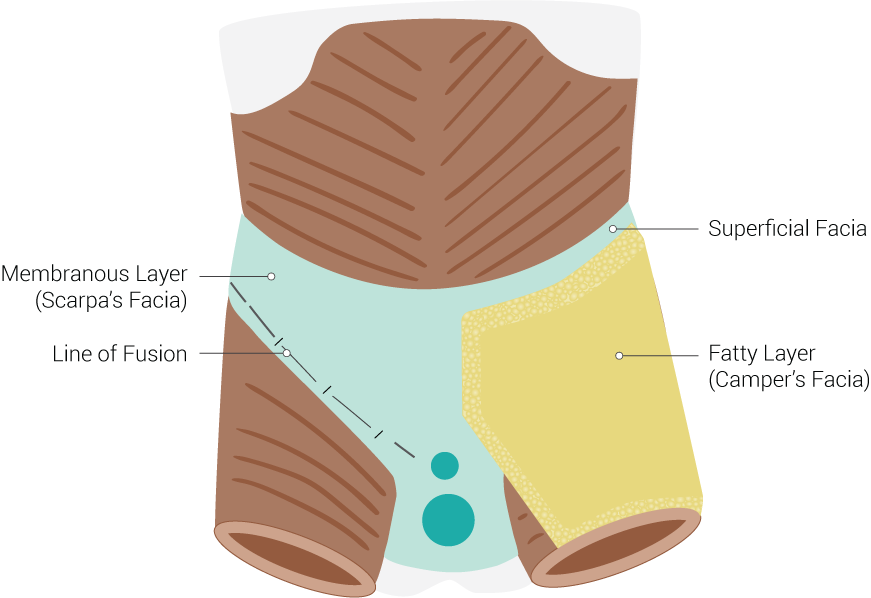

Scarpa's fascia is a membranous layer of the anterior abdominal wall. Passing through the abdominal wall layers from outside to inside nine distinct layers are identified: skin, subcutaneous tissue, superficial fascia, external oblique muscles, transversus abdominis muscle, transversalis fascia, preperitoneal adipose tissue, and peritoneum. One of these layers, the "superficial fascia" consists of two layers: a membranous Scarpa’s fascia and an outer fatty layer, the Campers’ fascia. Scarpa’s fascia lies below the Camper’s fascia and above the external oblique muscle. It is connected laterally to the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. Medially it fades into the linea alba and pubic symphysis. In the upper thigh just below the inguinal ligament, it blends in with the fascia lata. Scarpa’s fascia is named based on the region in which it is present. Scarpa’s fascia extends superficially to the spermatic cord and scrotum, where it is known as the dartos fascia. From within the scrotal area, the fascia is traceable backward, where it continues as Colles fascia as it blends with the deeper layers of the perineum. In females, Scarpa’s fascia extends into the labia majora. Scarpa’s fascia is a vital structure that providers need to be cognizant of because of its role in the repair of abdominal incisions and its clinical significance in forming fascial planes that limit bodily fluid extravasation.

Structure and Function

Scarpa’s fascia is a dense collagenous connective tissue layer of the anterior abdominal wall. It is considerably thinner than Camper’s fascia. It contains a large number of orange elastic fibers and loose connective tissue. Scarpa’s fascia serves an essential role in separating the overlying Camper’s fascia (fatty layer) from the muscle's underneath. It also allows Campers' fascia to slide freely over the underlying layer of the abdominal wall (external oblique fascia or rectus sheath) that reduces the friction of muscular force and aids in abdominal muscle flexion, extension, and rotation. Due to the parallel orientation of collagenous fibers to the direction of force, Scarpa’s fascia can withstand immense unidirectional tension forces. This feature allows the fascia to provide a supportive yet pliable case for the nerves and blood vessels transiting through and between the muscles. As part of the abdominal wall, Scarpa’s fascia also protects the organs lying within the abdominal cavity.

Embryology

Mesoderm, also known as the “middle layer,” gives rise to nearly all the connective tissues present in the human body. During embryogenesis, the mesoderm layer found on either side of the notochord, also known as the paraxial mesoderm gives rise to sclerotome and dermomyotome. The sclerotome forms the vertebral body, whereas the dermomyotome can further divide into dermatome and myotome that eventually forms the dermis and skeletal muscle, respectively. In humans, dermatome is identifiable around the third week of embryogenesis. Scarpa’s fascia, a connective tissue layer of the skin, has its origin from the dermatome.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The anterior abdominal wall receives its blood supply from the intercostal, subcostal, lumbar, and epigastric arteries. The supply to the lateral aspect of the abdominal wall comes from the inferior posterior intercostal arteries and lumbar arteries branching off the descending aorta. Scarpa’s fascia receives most of its blood supply from the epigastric vessels. Superior epigastric vessel branches of the internal thoracic artery course its way into the rectus sheath and eventually anastomoses with the inferior epigastric artery at the umbilicus. The inferior epigastric artery has its origin from the external iliac artery.

Lymphatic drainage of the abdominal wall (Scarpa’s fascia and other associated structures) below the umbilicus occurs through the superficial inguinal nodes.[1] Lateral abdominal wall lymph drains to the upper lateral quadrant of the superficial inguinal nodes. The medial abdominal wall lymph, on the other hand, targets the upper medial quadrant of superficial inguinal nodes.

Nerves

Abdominal wall layers receive segmental sensory innervation in a dermatomal distribution. The skin sensation around the umbilicus corresponds to the T10 dermatome. The intercostal nerves (T7-T11), the subcostal nerves (T12) become the anterior cutaneous nerves as they pass through the rectus sheath towards the skin. The iliohypogastric and the ilioinguinal nerves (L1) also provide sensory innervation to the skin. The iliohypogastric nerve takes the sensory information from the skin above the suprapubic area. The ilioinguinal nerve provides sensation to parts of the skin above labia majora and medial thigh. All these nerves pass through Scarpa’s fascia as they make their way to the skin.

Muscles

Muscles of the abdominal wall consist of the external oblique, internal oblique, transversus abdominis, and rectus abdominis. The external oblique is the outermost muscle of the anterior abdominal wall that arises from the eighth rib and attaches to the anterior iliac crest. The internal oblique muscle fibers find its origin from the thoracolumbar fascia, run cranially and anteriorly, attaching to the lower ribs and xiphoid process. Transversus abdominis fibers lie obliquely on the lateral aspect of the abdomen. It originates from lower costal cartilages, lumbar fascia, iliac crest, inguinal ligament, and attaches to the linea alba and pubic symphysis. Whereas, the rectus abdominis muscle fibers course along medially the entire length of the abdomen and attaches to the xiphoid process and lower costal cartilages cephalad and pubic bone and pubic symphysis caudad. Scarpa’s fascia lying directly above the external oblique serves as an essential structure that separates the underlying anterior abdominal wall muscles from the skin and subcutaneous tissue lying above.

Physiologic Variants

Scarpa’s fascia is found predominantly in the lower abdomen with well-developed fibers that course along the lateral aspect of the abdomen just superficial to the rectus sheath. Compared to the lateral aspect, the fascia is not as well developed along the midline of the abdomen. Scarpa’s fascia was previously believed to be restricted to the lower abdomen and perineum. As per recent radiological findings, the fascia extends over the entire torso.[2][3] Researchers found the variation in the arrangement and thickness was related to the body region, and gender.[4] The membranous layer of superficial fascia or the Scarpa's fascia is found thicker in posterior than anterior parts of the body. There are reports that it tends to be more pronounced in females than in males.

Surgical Considerations

Scarpa’s fascia plays a significant role during the healing process of the abdominal incisions.[5] Recent reports suggest the preservation of Scarpa’s fascia during abdominoplasty reduces the formation of seroma postoperatively.[6] Most frequent complication associated with abdominoplasty is seroma, a collection of serous or haemoserous fluid. Taking care to leave the adipose-fascial tissue undisturbed as much as possible, is important to reduce the duration and volume of drained fluid, which in turn decreases the length of hospital stay. Scarpa’s fascia preservation during abdominoplasty has also shown better outcomes in terms of good aesthetic results.

Another critical role of Scarpa’s fascia that is under investigation is its use in reconstructive surgery. Scarpa’s adipofascial flap is indicated for wide scalp defect repair.[7]

Clinical Significance

The initial belief was that Scarpa fascia prevented hernia formation, but this is not true. The fascia is not strong at all. Today the thinking is that the superficial fascia acts as a scaffolding that attaches the abdominal wall skin to the deeper layers so that there is no sagging.

During certain medical disorders including acute pancreatitis, fluid may collect in pockets created by fascial planes, or if there is a rupture, one may see bruising as in Grey Turner sign or Cullen sign. Skin discoloration (Grey Turner sign) boundaries observed in extraperitoneal hemorrhage correlate with the firm attachment sites of the Scarpa's fascia to the external oblique aponeurosis.[8] Similarly, discoloration seen due to leakage of bile in the retroperitoneal space, also known as Fox’s sign, correlates well with the caudal attachments of the Scarpas' fascia to the fascia lata of the thigh.[9] If the volume of fluid leak is overwhelming, then the discoloration is not limited to the lower abdomen and may be observed extending up in the torso. The upper boundary of discoloration seen in such cases results from Scarpa’s fascia adhering firmly to the deep fascia below the clavicle and upper axilla.[10]

Trauma or surgery can lead to scar tissue formation or adhesions that spans adjacent structures. Due to the presence of such scar tissues, fascia can eventually fail to make the original connections between structures. In some cases, fascial stiffness may also undergo alteration, causing reduced shearing ability.[11]