Introduction

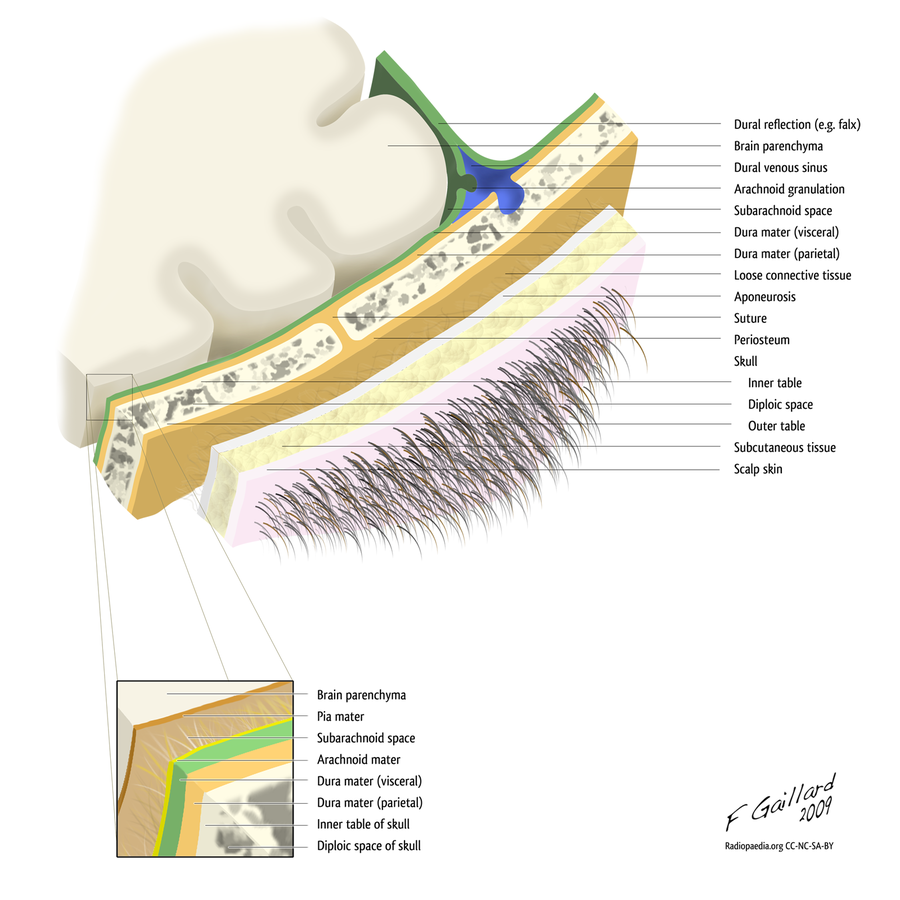

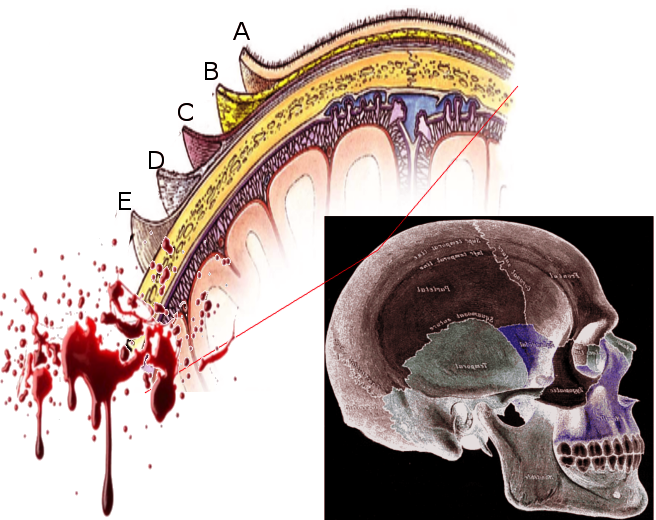

The scalp is composed of soft tissue layers that cover the cranium. It is an anatomic region bordered anteriorly by the human face, and laterally and posteriorly by the neck. It extends from the superior nuchal lines and occipital turbulences to the supraorbital foramen. Aesthetically, it serves as an area where hair can grow and physically, as a barrier that defends the body from foreign irritation. There are five layers to the scalp: the skin, connective tissue layer, galea aponeurotica, loose areolar connective tissue, and the pericranium.

Structure and Function

The scalp serves as a physical barrier to protect the cranial vault from physical trauma and potential pathogens that can cause infection.[1] In addition to its physical defenses, the scalp is important aesthetically. Hair grows on the skin of the scalp to not only aid in heat conservation but to also plays a role in an individual's appearance and sexual signaling. The first layer is the skin, which is thick and contains hair follicles and sebaceous glands. The hair follicles can extend into the dense connective tissue layer, where the nerves, lymphatics, and the vascular supply of the scalp reside. The galea aponeurotica, also called the epicranial aponeurosis, is a strong and immobile connective tissue layer continuous with the occipitofrontalis muscle. It is firmly attached to the subcutaneous dense connective tissue layer and serves to prevent stretching of the scalp, especially during surgery, which beneficially prevents complications. The loose connective tissue is important to the mobility of the scalp. It also serves as a flexible plane that separates the top three layers from the pericranium. The pericranium is the deepest layer of the scalp that is composed of dense irregular connective tissue. It tightly adheres to the calvarial bone of the skull. It contains the vascular supply that is vital to supporting the underlying calvarium.[2][3][4]

Embryology

The ectoderm is the outermost layer of embryonic tissue in the developing fetus. The notochord induces a process that separates the neural ectoderm from the external ectoderm. This creates a neural tube and crest, which forms the nervous system separate from the external ectoderm, which forms the epidermis. Also, the process of gastrulation creates mesoderm that derives from the overlying ectoderm. The epidermis gives rise to the epidermis consisting of the skin of the scalp while the mesoderm gives rise to the connective tissue composing the subsequent layers of the scalp.[5]

Aplasia cutis congenita is a congenital disorder characterized by the partial absence of skin in a specific region at birth. The region is usually the vertex of the scalp, but can also affect other parts of the body including the trunk and extremities. It can affect the epidermis alone or can cause a focal absence of the underlying layers, including the dermis, bone, or dura. The exact mechanism of aplasia cutis congenita is unclear but is thought to be associated with chromosomal abnormalities, teratogens, intrauterine problems, thrombotic events, and trauma.[6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

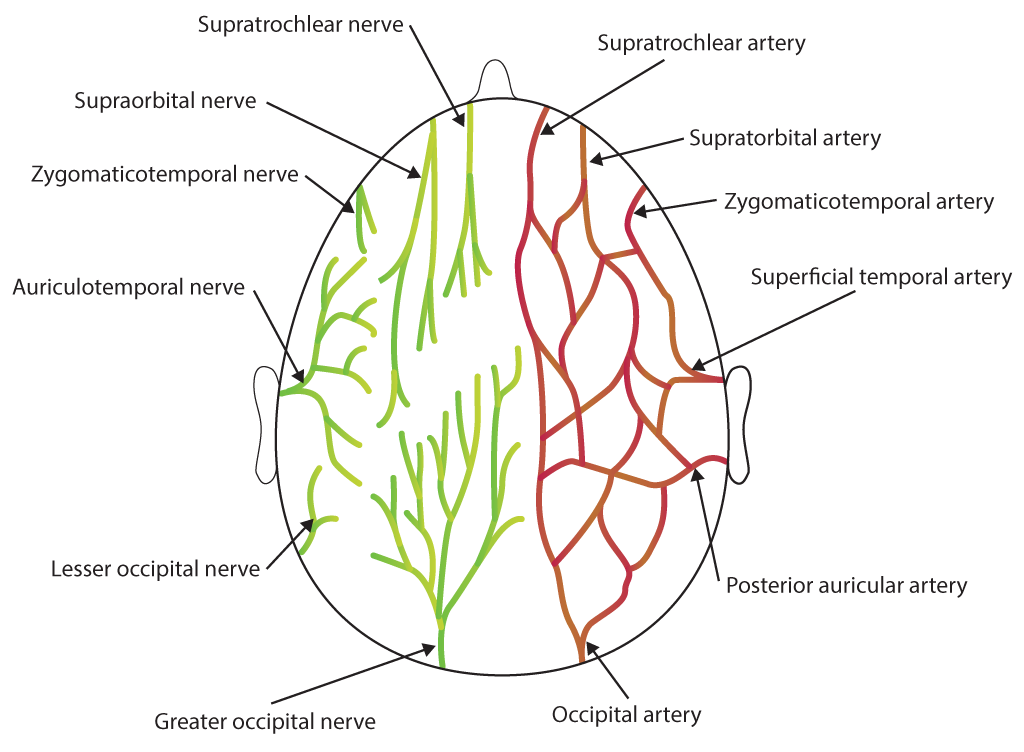

The vascular supply to the scalp comes from the common carotid artery, posterior intercostal arteries, and the terminal branches of the subclavian artery. These arteries connect through an impressive network of anastomoses, with anastomoses in the temporal region being the most numerous,

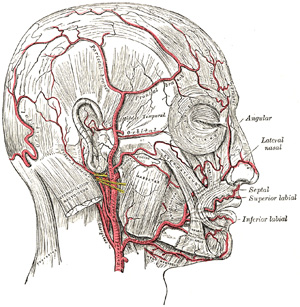

The common carotid artery bifurcates into the internal and external carotid arteries at the carotid sinus. Both give off branches that supply different areas of the scalp. The external carotid branches off to form the superficial temporal, posterior auricular, occipital, and the angular artery.

The superficial temporal artery, the terminal branch of the external carotid artery, passes over the posterior aspect of the zygomatic and divides into the frontal and parietal branches. The frontal is a terminal branch that runs a tortuous course in an anterosuperior direction across the temple. It supplies the anterior temple, superior to the eyebrows, while the parietal branch supplies the parietal region of the scalp. The posterior auricular artery originates superior to the stylohyoid and digastric muscles and travels to the deep tissues that intersect between the mastoid process and the cartilage of the ear. It supplies scalp posterior and superior to the auricle. The posterior auricular artery proximally gives off the occipital artery. The occipital artery ascends superiorly to penetrate the fascia between the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid. From there it tortuously ascends, and supplies the superficial fascia of the posterior scalp superior to the nuchal line, while also anastomosing with the superficial, posterior auricular arteries and the contralateral occipital artery. The posterior scalp inferior to the nuchal line is supplied by an association of vessels that also supply the trapezius and splenius capitis muscles. These vessels derive from the transverse cervical and posterior intercostal arteries.

The internal carotid artery gives rise to the ophthalmic artery that branches into the supratrochlear and supraorbital arteries that supply the anterior portion of the scalp. Both arteries arise from the skull through the supraorbital foramen and anastomose with their contralateral arteries and the superficial temporal artery to dominate the supply to the anterior scalp.[3][4][7][8]

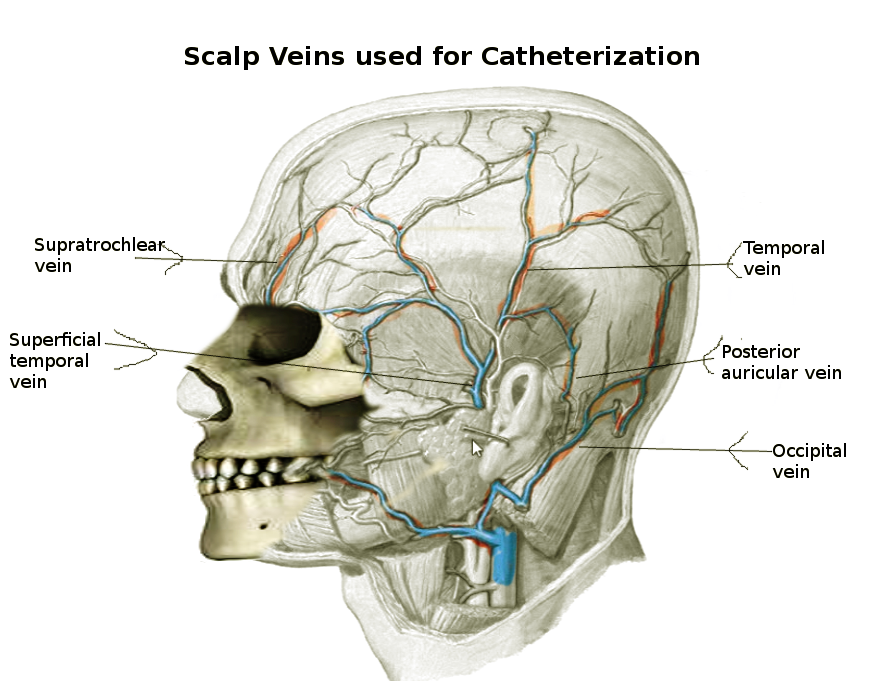

The scalp drains into superficial and deep venous systems. The superficial veins follow their respective arteries. The supraorbital and supratrochlear veins drain the superficial scalp anteriorly. While the superficial temporal, occipital, posterior auricular drain the superficial scalp posteriorly. Like the artery, the superficial temporal vein has parietal and frontal branches. The frontal vein communicates with the dural sinuses via a connection with the parietal emissary vein. This vein, found in the loose areolar connective tissue layer, runs superiorly along the lateral side of the head where it penetrates the cranium and communicates with the superior sagittal sinus.

The pterygoid venous plexus is responsible for draining the deep scalp. It is between the temporalis and lateral pterygoid muscles. The plexus is comprised of veins that are named after tributaries of the maxillary artery. These veins include the middle meningeal, sphenopalatine, buccinator, pterygoid, deep temporal, masseteric, infraorbital, and alveolar veins. The pterygoid plexus also has a communicating vein that travels through the inferior orbital fissure to connect the cavernous sinus to the ophthalmic vein. The plexus eventually drains in the maxillary vein.[9]

The lymphatic vessels of the scalp are located in the subcutaneous connective tissue layer and follow the venous drainage. In general, the anterior portions of the scalp drain through the parotid nodes, which continue to drain through the deep cervical and submandibular lymph nodes. The scalp posterior to the auricle drains to the occipital and posterior auricular (mastoid) lymph nodes. The mastoid lymph nodes specifically drain the area of the scalp located directly posterior to the ear and drain into the occipital lymph nodes. The occipital lymph node drainage covers the rest of the posterior scalp.[9]

Nerves

The ophthalmic division (V1) of the trigeminal nerve branches into the frontal nerve, which eventually bifurcates into the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves. These nerves supply sensation to the scalp anteriorly.

Laterally, sensory innervation is from the zygomaticotemporal and the auriculotemporal nerve, which branch off the maxillary division (V2) and the mandibular division (V3) of the trigeminal nerve, respectively.

Posteriorly, the scalp receives innervation by the lesser and greater occipital nerves. The lesser spinal nerve originates from the cervical plexus and provides sensory innervation specifically to the scalp posterior to the ear in a lateral distribution. The greater spinal nerve comes from the dorsal rami of the cervical spinal nerve 2 (C2), specifically innervating the posterior scalp in a superior distribution, up to the vertex.[3][4][10]

Muscles

As previously mentioned, the galea aponeurotica is a continuation of the occipitofrontal muscle. The occipitofrontalis muscle is split into the occipital and frontal bellies. The frontalis belly originates from the galea aponeurotica anteriorly and inserts into the superior orbicularis oculi at the level of the eyebrow. The occipitalis muscle origin is a posterior attachment at the mastoid and superior nuchal lines and inserts on the galea aponeurotica. These muscles are innervated by the superior zygomatic and posterior auricular nerve, respectively. They work in conjunction to pull the scalp back and elevate the eyebrows. The contraction of the frontalis muscle specifically creates wrinkles on the forehead. Of note, the loose connective tissue layer extends deep to the muscles. Bleeding into this space can track down to the orbicularis oculi causing a periorbital hematoma, more commonly known as a “black eye.”[8]

Physiologic Variants

The intricate network of arteries that interconnect and form the blood supply to the scalp is susceptible to considerable variation between different individuals. For example, some individuals have small superficial temporal and occipital arteries that cannot adequately supply their respective areas on the scalp. In compensation, these people have significantly larger posterior auricular arteries. Also, the posterior auricular artery can directly anastomose with the supraorbital artery and contribute to the supply of the anterior scalp and forehead.[7][11]

Surgical Considerations

As discussed in the previous section, no matter the variation, the rich array of anastomoses will cover the complete blood supply to the scalp. In patients who have traumatically experienced a complete avulsion of the scalp, surgical repair of just one of the arteries can successfully replant the supply of the scalp and prevent necrosis.[3][11]

The mobility and flexibility of the loose areolar connective tissue allow smooth separation between the upper layers and pericranium. Due to its ability to be easily dissected, this layer of the scalp serves as an essential plane of entry in craniofacial surgery. It provides the ability for the creation of scalp flaps that can preserve vital neurovascular structures in superficial layers of the scalp.[8]

Clinical Significance

The loose areolar connective tissue is a harbor for a potential infection that can spread to the meninges. Named ‘the danger zone’ of the scalp, the tissue contains valveless emissary veins that have direct access to the cranial cavity. Pus and blood can build up in the flexible tissue, and provide a route for meningitis.[9]

Tearing of the emissary veins in the loose areolar connective tissue layer causes the build-up of blood that gets trapped between the tense tissue of the galea aponeurotica and the pericranium. This condition is called a subgaleal hematoma (SGH). Although it can present in adults, SGH usually occurs in neonates after delivery with vacuum assistance. It can also present in pre-school aged children with innocent head trauma (i.e., brushing hair).[12]

This extensive network of anastomoses, especially the anastomosis of the superficial temporal vein with the posterior auricular and occipital veins, sets up the potential for extensive bleeding with any deep laceration to the scalp. This bleeding also becomes exacerbated by the fact that the dense connective tissue layer firmly adheres to the blood vessels of the scalp, preventing vasoconstriction.[9]

Giant Cell Arteritis is a medium to large artery vasculitis that mostly affects patients above the age of 70. Some of its symptoms include pain in the temple region, headache, flu-like symptoms, jaw claudication, and can be associated with polymyalgia rheumatic. Its etiology is unknown, but it is due to granulomatous inflammation of the superficial temporal artery. Diagnosis is usually made clinically but can be confirmed with a biopsy of the superficial temporal artery.[13]

The superficial skin of the scalp has a dark and warm environment filled with hair follicles and heavy sebum production that makes it prone to fungal infection. These different mycotic infections can cause varying degrees of pruritus, alopecia, inflammation, scaling, and scarring of the epidermis. Different infections are caused by different organisms that dictate what kind of treatment is necessary for cure. For example, dandruff and seborrheic dermatitis are due to the Malassezia fungus and can be treated topically, while tinea capitis, also known as scalp ringworm, is due to infection by the dermatophytes Tricophytan or Microsporum and are usually treated systemically.[1]

Psoriasis is an autoimmune disorder that can cause scaly lesions on the scalp in 50% of cases. Immune cells migrate from the dermis to the epidermis and signal for the excessive proliferation of the superficial epidermal layer of the scalp. Like the infectious disorders of the scalp, psoriasis can correlate with a certain degree of pruritus, scaling, scarring, and alopecia that is variable between different individuals. At this point, there are no cures, but the disease is managed based on the severity of the disease. If Psoriasis only affects a certain area like the scalp, it can be treated locally with topical corticosteroids, emollients, and vitamin D analogs. If the Psoriasis affects multiple parts of the body and causes systemic symptoms like arthritis, it should receive treatment with systemic medications like methotrexate.[1][14]