Continuing Education Activity

Rhombic flaps, characterized by their quadrilateral shape resembling a rhombus, are versatile local transposition flaps commonly employed in reconstructive surgery for small- to medium-sized skin defects. Originating from utilizing adjacent skin laxity, these flaps offer excellent cosmetic outcomes and are particularly useful in head and neck reconstructions after skin cancer resection. Variations of rhombic flaps, including the Limberg, Dufourmental, Webster, Quaba-Sommerlad, and note flaps, provide surgeons with options tailored to specific defect characteristics and patient needs. While effective, mastering the nuances of flap design, elevation, and closure is crucial to optimize outcomes and minimize complications in rhombic flap reconstructions.

Clinicians participating in this course gain comprehensive knowledge and skills essential for proficiently utilizing rhombic flaps in reconstructive surgery. Participants will learn to select the most appropriate flap variant for specific clinical scenarios through a detailed explanation of flap design principles, orientation, and techniques. Additionally, the course will cover intraoperative and postoperative management strategies, including flap assessment, complication recognition, and patient communication. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and emphasizing evidence-based practice, clinicians will enhance their competence in rhombic flap reconstruction, ultimately improving patient outcomes and satisfaction.

Objectives:

Identify the appropriate candidates for rhombic flap reconstruction based on the skin defect's size, location, and nature.

Differentiate between rhombic flap designs, including Limberg, Dufourmental, Webster, Quaba-Sommerlad, and note flaps, considering their advantages and limitations.

Assess flap viability intraoperatively and postoperatively, monitoring for ischemia or venous congestion signs.

Collaborate with interdisciplinary teams, including plastic surgeons, nurses, and wound care specialists, to ensure comprehensive care for patients undergoing rhombic flap surgery.

Introduction

Rhombic flaps are versatile geometric local transposition flaps commonly utilized for reconstructing small to medium-sized skin defects, particularly after skin cancer resection in the head and neck area. However, their utility extends beyond this, proving effective in various anatomical regions and pathologies, including spina bifida, burn contractures, chronic pilonidal sinuses, and hand and breast reconstruction.[1][2][3][4][5] Like other local flaps, rhombic flaps take advantage of skin laxity adjacent to a defect to permit reconstruction with skin with characteristics similar to those of the excised tissue. This approach enhances cosmetic outcomes compared to alternative reconstructive methods such as skin grafting and regional or free tissue transfer.[6]

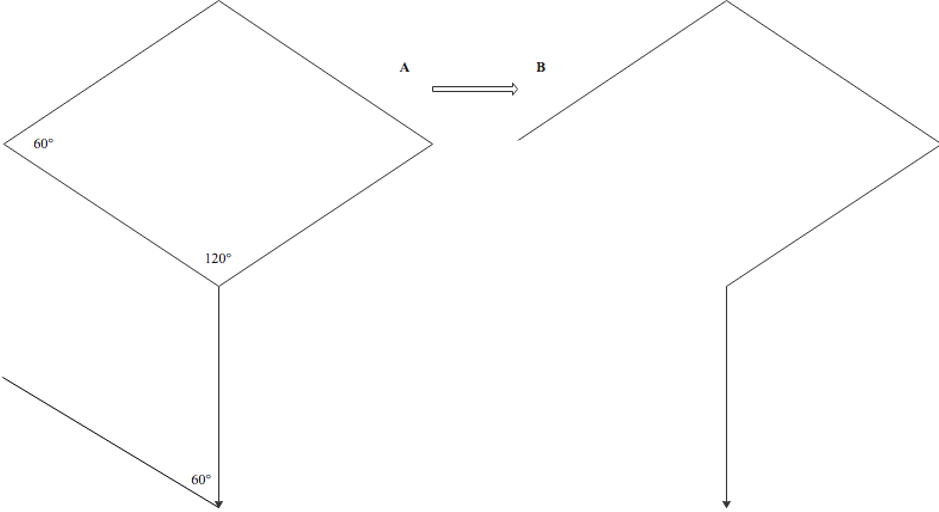

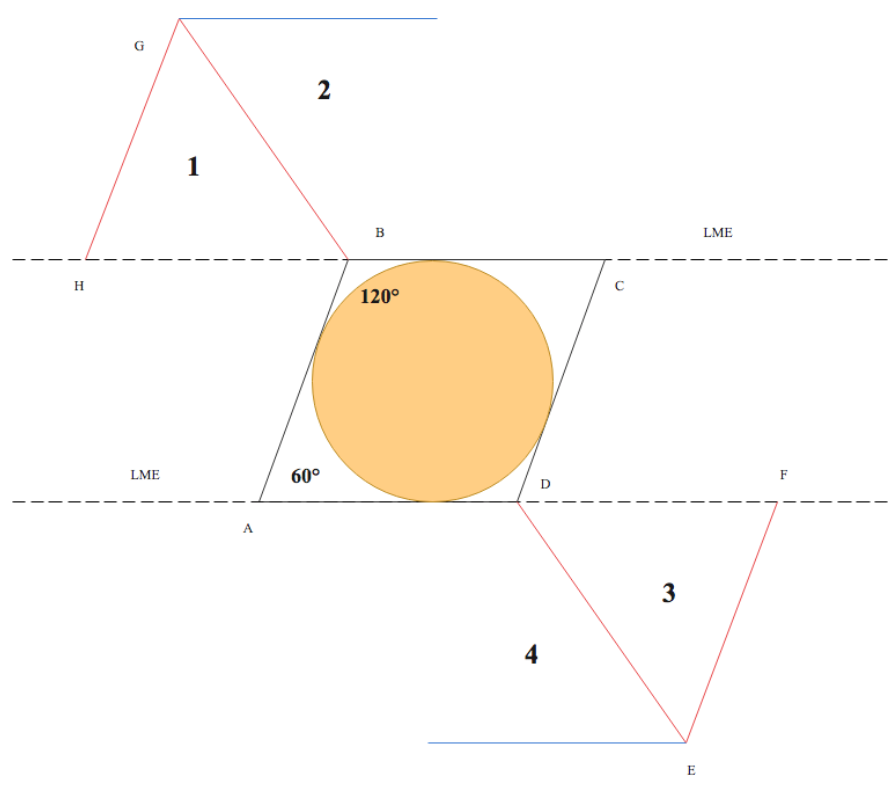

The term "rhombus" originates from Euclidean geometry, denoting a quadrilateral with 4 equal-length sides and opposing equal acute and obtuse angles. Conversely, "rhomboid" refers to any parallelogram with 2 acute and 2 obtuse angles. "Rhombic" accurately describes flaps resembling a rhombus, while "rhomboid" pertains to those resembling a parallelogram. Russian surgeon Alexander Limberg first described the rhombic flap in 1945 and published his findings in English in 1966.[7] Limberg's design features a characteristic quadrilateral rhombus shape, facilitating transposition through a 60° arc into corresponding skin defects (see Image. Classic Limberg Rhombic Flap Design).

Common Rhombic Flap Variations

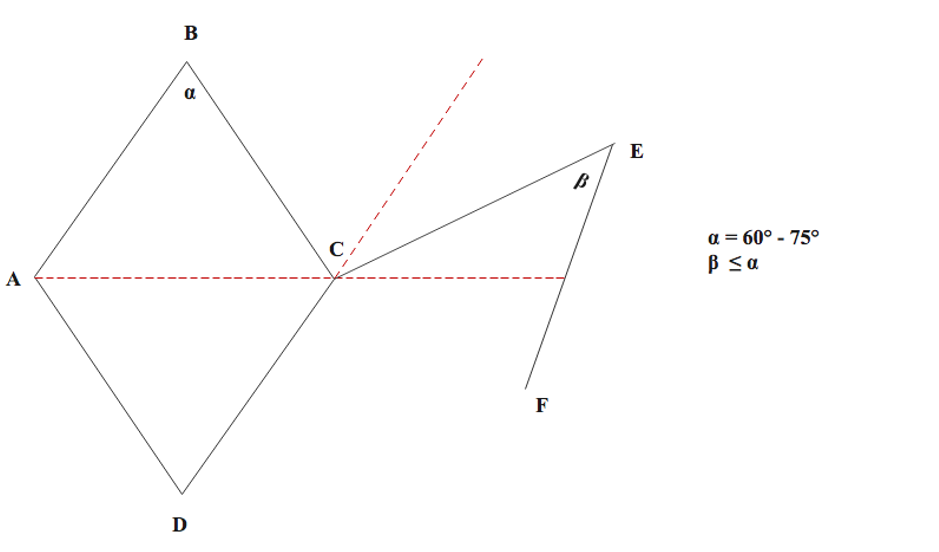

In 1962, Claude Dufourmental refined Limberg's rhombic flap design, proposing a modification involving a narrower flap with a more acute rotation angle. This adjustment aims to facilitate closure and minimize the standing cutaneous deformity at the pivot point of transposition (see Image. Dufourmental Rhombic Flap Modification).[8] When designing the defect, the acute angle (α) must fall between 60° and 75°. The flap itself is created by aligning the first incision (CE) to bisect the angle between the line of the short diagonal axis of the rhombus defect and its adjacent side, with the incision's length equaling 1 side of the defect. The flap angle (β) may equal the defect angle (α) or be slightly smaller if needed, providing flexibility in design and placement. Unlike the Limberg rhombic flap, the shape of the Dufourmental flap doesn't precisely match the defect; however, complete closure occurs through secondary movement of surrounding skin, similar to the Limberg flap. Advocates of the Dufourmental modification argue its superiority over the Limberg flap due to improved blood supply and easier donor site closure facilitated by a wider pedicle and a more adaptable design.[8][9][10] Sebastian et al reported the Dufourmental flap's superior versatility in surgical reconstruction compared to the Limberg flap, particularly in chronic pilonidal disease (see Image. Limberg Rhombic Flap for Pilonidal Sinus).[11]

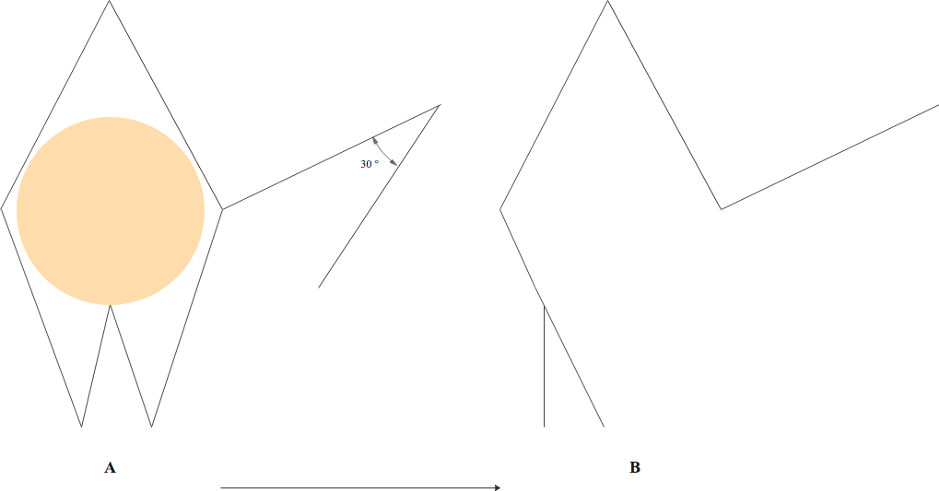

In 1978, Webster modified Limberg's rhombic flap design, incorporating a more acute 30° flap angle and an M-plasty to close the defect base (see Image. Webster Rhombic Flap Modification). The narrower 30° flap angle aims to decrease tension during donor site closure. At the same time, the M-plasty divides the rotation arc between two 30° angles, enhancing tension distribution and reducing tissue distortion at the flap's pivot point. In Webster's original case series, favorable outcomes were reported, including reduced scar widening and areas of skin excess, attributed to a more balanced tension distribution.[12] Like the Dufourmental modification, the Webster rhombic flap design necessitates significant secondary tissue movement for closure, as the flap's shape does not precisely match the defect.

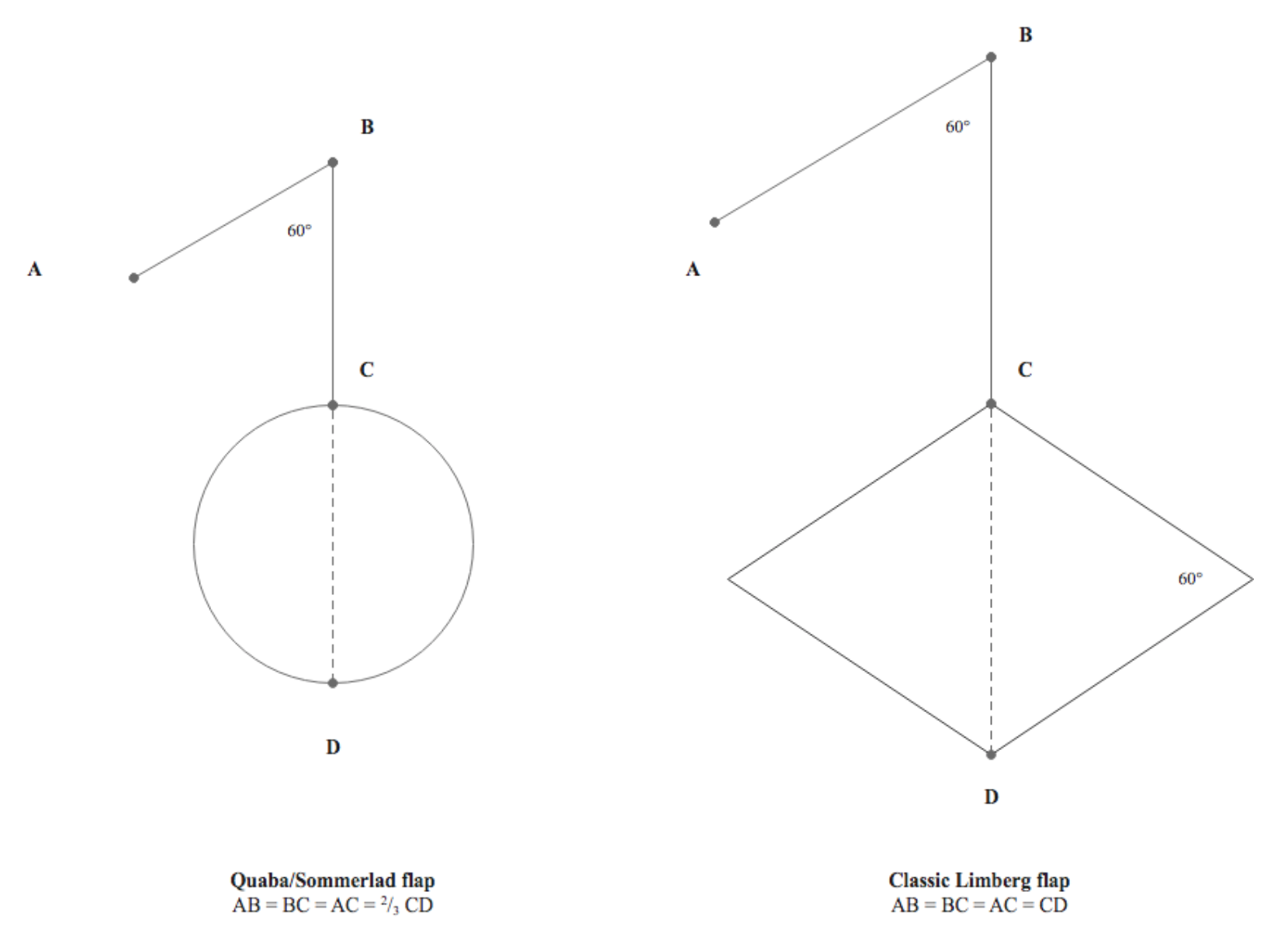

In 1987, Quaba and Sommerlad introduced a rhombic flap modification for reconstructing circular defects. This technique involves utilizing a rhomboid flap to reconstruct a round defect, with each side of the flap measuring two-thirds the diameter of the defect and a flap angle of 60° similar to Limberg's original description (see Image. Comparison of Quaba-Sommerlad Modification and Classic Limberg Rhombic Flap Design.). The authors documented a series of 175 patients with head and neck skin defects reconstructed using Quaba-Sommerlad flaps. Advantages cited over the classic design included enhanced flexibility in flap transposition and donor site orientation, along with the absence of a need to sacrifice healthy tissue to create a rhombus-shaped defect.[13]

The Quaba-Sommerlad flap shares similarities with another rhomboid transposition flap known as the "note flap," first described by Walike and Larrabee in 1985 (see Image. Note Flap).[14] Named for resembling a musical eighth note in certain orientations, the note flap employs a quadrilateral flap to close circular defects. However, unlike the Quaba-Sommerlad rhomboid flap, the note flap's first limb is incised tangentially to the circular defect, making it distinct among rhombic flap variants. Additionally, the side of the note flap measures 1.5 times the diameter of the defect, rather than only two-thirds. Both the note flap and the Quaba-Sommerlad flap utilize 60° flap angles in their designs.

Numerous authors have described multiflap variants involving 2, 3, and even 4 rhombic flaps.[15][16][17][18] These variants have been applied to reconstruct larger defects and in areas with reduced pliability of adjacent skin. El-Tawil et al published a series of 8 patients with pilonidal sinus disease reconstructed with double rhombic flaps, resulting in low recurrence and complication rates and obviating the need for complex reconstruction. Additionally, successful reconstruction of meningomyelocele defects with triple and quadruple rhombic flaps has been reported, yielding positive patient outcomes.[17][19] While numerous designs of rhombic flaps exist for various anatomical sites, this article primarily focuses on the widely reported Limberg flap method employed in reconstructing head and neck skin defects.

Anatomy and Physiology

The rhombic flap is a "random pattern" local flap because it relies upon the unnamed vessels of the subdermal plexus for its blood supply, like the vast majority of other local flaps.[20][21][22][23] This plexus, situated at the junction of the reticular dermis and subcutaneous fat, gives rise to arterioles that supply the dermis and epidermis.[24] The rich anastomotic blood supply of the subdermal plexus ensures perfusion and venous drainage for random pattern flaps without needing a named artery within the flap itself, as seen in axial flaps.

Preserving the subdermal plexus is essential during flap elevation. This is achieved by including a thin layer of subcutaneous fat on the flap's undersurface and avoiding aggressive dissection at the flap's base, which remains connected to the surrounding skin.[25] Successful flap transposition relies on careful orientation, considering the lines of maximal extensibility and relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs). The rhombic flap should be oriented so that its short diagonal axis is perpendicular to the RSTLs.[10][26]

Particularly in the head and neck region, placing incisions within existing creases or boundaries between aesthetic subunits will leave the least conspicuous scars.[27] Furthermore, distributing tension with consideration for adjacent facial landmark structures with free margins helps prevent distortion, minimizing potential complications such as ectropion, nasal alar notching, and eyebrow asymmetry.[26]

Indications

Reconstruction options for small- to medium-sized defects that cannot be closed primarily include local flaps or free skin grafts (see Image. Reconstructive Ladder).[28] Local flaps offer advantages over skin grafting, such as better color and texture matching and fewer wound sites, as they use skin adjacent to the defect for reconstruction. These flaps can be applied to various anatomical regions, particularly facial defects involving the cheek, eyelids, chin, temple, and nose.[27]

The choice between advancement, rotation, transposition, or interpolation flaps depends on factors such as the size and location of the defect, its relationship to surrounding structures, aesthetic subunit boundaries, and existing wrinkles or scars. Suppose a transposition flap is deemed the optimal reconstructive method. In that case, the decision then revolves around whether to utilize a bilobed flap, a rhombic flap, or a variant, typically based on surgeon preference.

Contraindications

In skin cancer surgery, incomplete oncological clearance is often considered an absolute contraindication to flap reconstruction. Consequently, reconstruction may be deferred until histopathological clearance can be confirmed or until Mohs micrographic surgery is performed. Relative contraindications may include patient factors such as heavy smoking, poorly controlled diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, anticoagulation therapy, prior radiation treatment, extensive sun damage to the area, or peripheral vascular disease, all of which may increase the risk of flap necrosis and wound healing complications.

While many medical comorbidities are modifiable, sufficient time for preoperative medical optimization, including smoking cessation, suspension of coagulant medication, and glycemic control, may be necessary. Certain anatomic regions should be avoided for local flap reconstruction due to poor adjacent skin laxity or proximity to landmarks vulnerable to tension-related disruption.

Equipment

The following equipment is necessary for rhombic flap creation:

Preparation

- Surgical site marker

- Measuring tape or caliper

- Local anesthetics such as lidocaine 1% with 1:200,000 adrenaline with a syringe and needles

- An antiseptic solution such as 1% chlorhexidine solution or povidone-iodine

- Surgical drapes

Intraoperative

- Scalpel (#15 blade)

- Forceps

- Dissecting scissors such as tenotomy scissors

- Suture scissors

- Skin hooks

- Bipolar electrocautery and topical thrombin

- Normal saline solution for washout

- Sutures: size and type depend upon the anatomical location and surgeon preference (eg, absorbable for deep dermal and nonabsorbable for simple interrupted)

Postoperative

- Sterile tape strips

- Skin adhesive

- Surgical dressing tape

- Additional dressings, if indicated

Personnel

Rhombic flap transfer is usually performed by plastic surgeons, maxillofacial surgeons, dermatologists, or otorhinolaryngologists. Depending on the procedure setting, additional staff will be required in addition to the surgeon. Only a single assistant may be necessary if performed in an outpatient clinic. A surgical technician, a circulating nurse, an anesthesia provider, and potentially a surgical first assistant will be present in the operating room.

Preparation

Before performing a rhombic flap procedure, informed consent should be obtained from the patient. This process involves providing a comprehensive explanation of the procedure, aftercare instructions, potential benefits, risks of complications, and a discussion of alternative management options. Patients should be given adequate time to consider this information before signing the consent form. Additionally, it is advisable to document preoperative photographs in the patient's medical record.

Rhombic flaps are typically transferred under local anesthesia for small- to medium-sized facial defects. However, larger or more complex defects, especially those complicated by patient comorbidities, may necessitate general anesthesia or sedation. In such cases, a preoperative anesthetic evaluation may be required to ensure patient safety.

Technique or Treatment

Once hemostasis within the defect has been ensured, the initial step in rhombic flap transfer involves designing the flap and delineating the planned incisions. This process entails identifying the adjacent tissue from which the flap should be elevated. Primary considerations include assessing areas with the greatest skin laxity (through palpation and pinch testing), the proximity of anatomical landmarks susceptible to tension-related distortion (such as eyelids, earlobes, lips, eyebrows, and nostrils), the orientation of relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs) and lines of maximum extensibility (LME), and the presence of aesthetic subunit boundaries or facial rhytides for scar concealment.

Once the donor site for the flap is identified, a rhombus is marked around the defect. The specific proportions of the rhombus vary depending on the type of rhombic flap planned. The defect should have opposing angles of 120° and 60° for a Limberg flap, ensuring adequate resection margins per relevant guidelines. The short axis of the defect runs between the 2 opposing 120° angles. The first limb of the flap incision continues along the short axis with a length equal to the sides of the defect. The second limb is drawn parallel to 1 side of the defect at a 60° angle from the first limb (see Image. Classic Limberg Rhombic Flap Design).[25]

The rhombus of a Dufourmental flap is similar in configuration to a Limberg flap, but the first limb of the flap is drawn to bisect the angle between the defect's short axis and a line extending from the defect's side. The second limb forms a 60° angle with the first (see Image. Dufourmental Rhombic Flap Modification). In the case of a Webster flap, the angle at the apex of the rhombus is 60°, but the opposing angle at the base of the defect is divided into an M-plasty. The flap is designed with its first limb perpendicular to the defect's side, while the second limb forms a 30° angle with the first (see Image. Webster Rhombic Flap Modification).

Regardless of the chosen variant, the rhombus should be oriented with the short axis of the flap parallel to the LMEs and perpendicular to the RSTLs to facilitate transposition through inherent skin laxity. Although each rhombus allows for 4 possible flap designs, only 2 are viable for ensuring the short axis of the flap is parallel to the LMEs (see Image. Rhombic Flap Designs Around a Defect). After the flap has been marked, the local anesthetic should be infiltrated under the planned flap and out to a 2- to 4-cm radius around both the flap and the defect.[29] The surgical field is then cleaned and draped before the procedure commences.

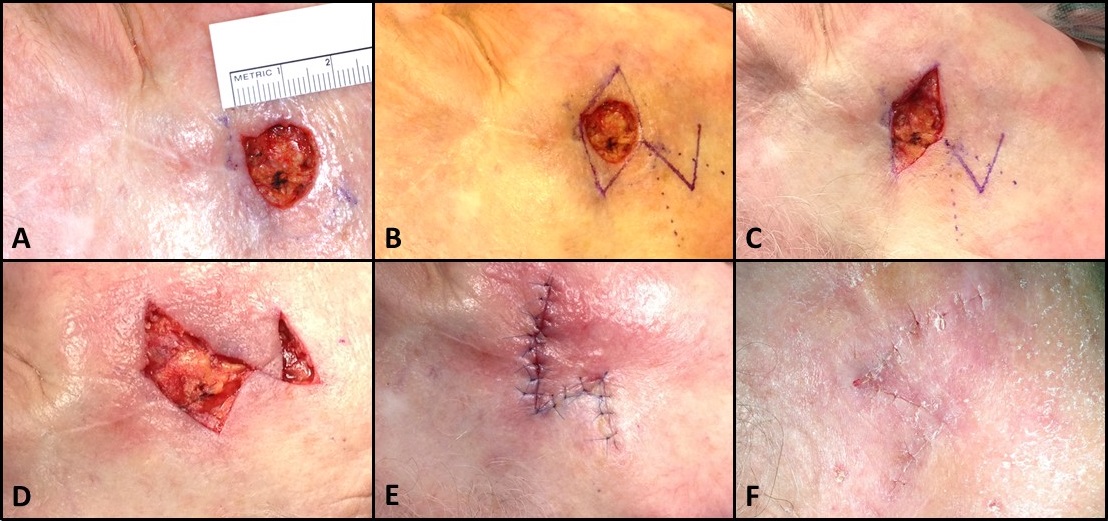

If necessary, the defect is converted into a rhombus by excising surrounding skin down to the subcutaneous layer, although this step is not required for Quaba-Sommerlad or note flaps. The flap is then incised with a scalpel and elevated in the subcutaneous plane using dissecting scissors, ensuring sufficient thickness to include the subdermal plexus. An assistant may provide counter-traction using skin hooks to aid in this process. Similarly, undermining up to 2 to 4 cm around the flap and defect enables secondary tissue movement for tension-free closure. However, undermining more than 2 to 4 cm may improve redraping but is liable to increase closure tension, somewhat counterintuitively.[30] While flap transposition is the primary tissue rearrangement component of this reconstruction method, secondary movement of surrounding skin towards the flap is also important. Essentially, rhombic flap transposition resembles an eccentric variant of the Z-plasty technique, where the Z-plasty flaps are asymmetric, and the rhombic flap serves as the smaller, more acutely angled flap. This concept is illustrated by the resulting Z-shaped scar after Dufourmental rhombic flap transposition (see Image. Rhombic Flap for Mohs Defect of the Right Cheek).

Following flap elevation and undermining, achieving thorough hemostasis with bipolar electrocautery is recommended to ensure a dry wound bed and minimize the risk of hematoma formation. However, caution should be exercised to avoid electrocautery on the undersurface of the flap unless absolutely necessary to prevent damage to the flap's delicate microvasculature. Alternatively, pressure application or topical thrombin can typically achieve hemostasis on the flap.

After elevation, the flap is transposed into the defect. The donor site should be closed first by bringing point F to point C (see Image. Dufourmental Rhombic Flap Modification); this is the point of maximum tension during closure. The remainder of the closure should be completed in 2 layers. On the face, buried, interrupted 5-0 poliglecaprone sutures in the deep dermis and simple, interrupted 6-0 polypropylene sutures on the skin surface are typically used. Suppose a standing cutaneous cone deformity arises at the pivot point near the base of the flap, point D (see Image. Dufourmental Rhombic Flap Modification). In that case, additional skin may be excised to correct the contour, ensuring the flap's base is not narrowed excessively to compromise circulation. A rule of thumb for a random pattern local flap on the face is that the width of the base should be at least one-third of the flap's length. On the trunk or extremities, the width-length ratio for a local flap is greater, at 1:2, due to relatively poorer cutaneous perfusion.

After completing the case and ensuring the flap appears well-perfused, a gentle compressive dressing is applied and left in place for 24 to 48 hours. Polypropylene sutures are removed 6 to 7 days post-surgery to prevent long-term suture marks ("train track" scars). Cyanoacrylate skin glue may be applied in mobile face areas to avoid wound dehiscence and scar widening.

Complications

Complications of rhombic flap reconstruction should be fully explained during the consent process and may be divided into general and specific complications. General complications common to most surgical procedures include pain, bleeding, bruising, infection, wound breakdown, damage to nearby anatomical structures, and unsightly scarring or dissatisfaction with the cosmetic outcome.

Specific complications of partial or complete flap failure are uncommon. Still, they can result from technical errors such as overly aggressive thinning and undermining the flap or closure under excessive tension (see Image. Local Flap Complication). Patient factors, including smoking, vasculopathy, or postoperative picking at the surgical site, can also contribute to flap failure.[27]

Hematoma accumulation under the flap can lead to inflammation and edema, compromising venous outflow and causing flap congestion. Prompt identification and drainage of hematomas are essential. Vascular compromise in a flap without a hematoma is typically due to venous obstruction. Topical nitroglycerin cream may promote vasodilation, but leech therapy may be necessary in some cases. Medicinal leeches relieve venous congestion by removing blood from the flap and improving perfusion through anticoagulation, facilitated by the presence of hirudin in their saliva. However, patients undergoing leech therapy should receive prophylactic fluoroquinolone antibiotics due to the risk of Aeromonas hydrophila transmission from leeches.

If salvage efforts fail, local wound care with minimal debridement of necrotic tissue is recommended, as the eschar acts as a "biological dressing." Healing by secondary intention may be necessary for resurfacing the area. Alternatively, readvancement of the flap's leading edge into the remaining wound may suffice if only the distal tip of the flap has failed, a common scenario due to relatively low perfusion pressure.

Additionally, disruption of lymphatic drainage may result in a "trapdoor" deformity characterized by persistent flap elevation relative to surrounding tissue, resulting in an abrupt step-off along incision lines. This phenomenon is more common in superiorly-based flaps, as inferiorly-based flaps typically have better lymphatic and venous drainage. Another complication is the "pincushion" deformity, where postoperative wound bed contraction or transfer of an oversized flap leads to a rounded, heaped-up appearance of the transferred tissue. Poor flap orientation planning may also result in scar tethering or webbing to adjacent anatomical structures, distorting aesthetically important features such as eyelids, lips, or eyebrows.[25] Additionally, specific anatomic regions may pose risks of damage to underlying structures; for instance, designing a flap within the temporal region may risk disruption to forehead motor function.

Clinical Significance

Rhombic flaps are highly versatile flaps that may be used to reconstruct various defects. When fundamental anatomical and mechanical principles are applied, favorable cosmetic and functional outcomes are obtained.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of rhombic flaps requires a coordinated effort among various healthcare professionals to ensure patient-centered care, optimize outcomes, promote patient safety, and enhance team performance. Physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals each bring unique skills and expertise to the team. Physicians and advanced practitioners play a crucial role in the initial assessment, surgical planning, and execution of rhombic flap procedures. Their expertise in surgical techniques and patient care guides decision-making throughout the process. Nurses provide preoperative education, assist in flap elevation and wound care, and monitor patients postoperatively for any signs of complications or flap compromise. Pharmacists play a vital role in medication management, ensuring appropriate pain management, prophylactic antibiotic administration, and monitoring for any drug interactions or adverse effects.

Interprofessional communication among team members is essential to clearly understand patient needs, surgical plans, and postoperative care instructions. Regular communication promotes collaboration, reduces errors, and improves patient outcomes. Care coordination involves seamless transitions between preoperative assessment, surgical intervention, and postoperative care, ensuring continuity and consistency in patient care. By working collaboratively and leveraging their respective skills, healthcare professionals can optimize patient-centered care, improve outcomes, enhance patient safety, and promote overall team performance in the context of rhombic flap procedures.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Achieving optimal patient outcomes for patients undergoing rhombic flap transfer depends upon well-orchestrated interprofessional team care. Although surgeons or dermatologists perform the surgery, they form only part of the extended healthcare team. The involvement of specialist nurses in the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative settings is essential to facilitating smooth patient care and promptly recognizing complications. Other allied health professionals play important roles, including physician associates, operating room staff, pathologists, and pharmacists.[31] The specialist multidisciplinary team of pathologists, radiologists, surgeons, and dermatologists in skin cancer is crucial to confirm adequate oncological clearance. These team members also coordinate ongoing surveillance and care.

After suture removal, patients should maintain regular follow-up appointments with the healthcare team to monitor the aesthetic outcomes of flap transfer, especially for facial reconstruction. Patients, especially those with darker complexions, are advised to avoid sun exposure to the site for 12 months to prevent postoperative scar hyperpigmentation. Sunscreen with a solar protection factor of 30 or higher is recommended outdoors. Additionally, many patients may benefit from dermabrasion to the site 6 to 12 weeks after surgery to enhance the color and texture match between the flap and surrounding skin.