Introduction

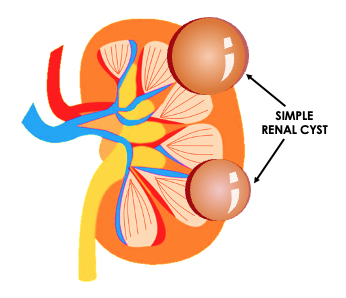

A renal cyst is the most common lesion of the kidney. Renal cysts are so ubiquitous that they are present in approximately 40% of the patients undergoing imaging. Cystic renal disease can be focal, multifocal, unilateral, or bilateral. Renal cysts can be acquired or the result of a congenital disease process. The acquired form is the most common.

Renal cysts can range from benign to malignant or indeterminate. A categorization system for adult renal cysts was introduced in the late 1980s, known as the Bosniak classification. It was introduced in attempts to standardize the characterization and management of renal cysts.[1][2][3]

The terminology of congenital renal cysts has changed throughout the years, with the current characterization known as the Potter classification. The Potter classification has four categories: Type I is infantile polycystic kidney disease, Type II is multicystic dysplastic kidney disease, Type III is adult polycystic kidney disease, and Type IV is obstructive renal dysplasia.[4]

Infantile polycystic kidney disease is also known as autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. ARPKD demonstrates no gender predilection with a ratio of 1:1. The age range of diagnosis is neonate to childhood, depending on the severity of the disease.[2]

Multicystic dysplastic kidney disease is a non-inherited kidney disease that develops in utero. It is most commonly unilateral, with a higher incidence on the left side. The diagnosis is often made while still in utero or very early in a neonate.[5][6][7]

Adult polycystic kidney disease is also known as autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. A patient with ADPKD has a normal appearance of the kidneys at birth and begins to develop multiple cysts bilaterally in their 20s to 30s.[8] It is the most common inherited cause of end-stage renal failure, with more than 50% of patients requiring dialysis by the age of 60 years.[8]

Obstructive cystic renal dysplasia results from an obstruction during development that causes scattered cysts throughout the affected kidney.[9][10]

Etiology

Autosomal recessive kidney disease is caused by a mutation in the PKHD1 gene located on chromosome 6, resulting in cyst formation in the collecting ducts.[2]

Multicystic dysplastic kidney disease is most commonly idiopathic.

Autosomal dominant kidney disease is caused by a mutation in either the PKD1 gene on chromosome 16 or the PKD2 gene on chromosome 4.[11][12]

Obstructive cystic renal dysplasia results from an obstruction of the ureter, bladder, or urethra.

Acquired renal cysts are most commonly idiopathic. They can develop in the infectious setting, can be a result of multisystem diseases such as Von-Hippel-Lindau and tuberous sclerosis, or can form during end-stage renal disease.[13]

Epidemiology

The presence of acquired renal cysts increases with advancing age. Simple renal cysts are the most common cystic renal lesions. They are thought to be present in up to 5% of the general population.[13] This prevalence increases to more than 25% in people older than 50 years of age.[13]

In the elderly population, renal cysts can account for up to 65% - 70% of renal masses. The prevalence of renal cysts was found to be higher in men compared to women in a retrospective magnetic resonance imaging study of 2,000 patients. They also reported a higher prevalence in patients with hypertension and a smoking history.[14]

Pathophysiology

Multicystic dysplastic kidney disease is caused by nonfunctioning kidney tissue in the affected area, which develops into cysts. It can ultimately lead to renal agenesis of the affected side.[15][16]

Obstructive cystic renal dysplasia results from an obstruction of the ureter, bladder, or urethra that increases pressure to the kidney, which creates cysts.

History and Physical

The presentation of a patient with cystic kidney disease varies with the underlying disease etiology. Physical examination is usually only pertinent to inherited renal disease, presenting as a palpable mass in a neonate or child.[2]

Patients with ADPKD commonly present with flank pain, renal failure, hypertension, or palpable masses.[8]

Acquired cystic kidney disease rarely becomes large enough to become palpable on physical examination.

Renal cysts are most often found incidentally during an ultrasound or cross-sectional CT imaging for other causes.

Taking a thorough family history is key to elucidating possible genetic factors in a patient with renal cysts.

Evaluation

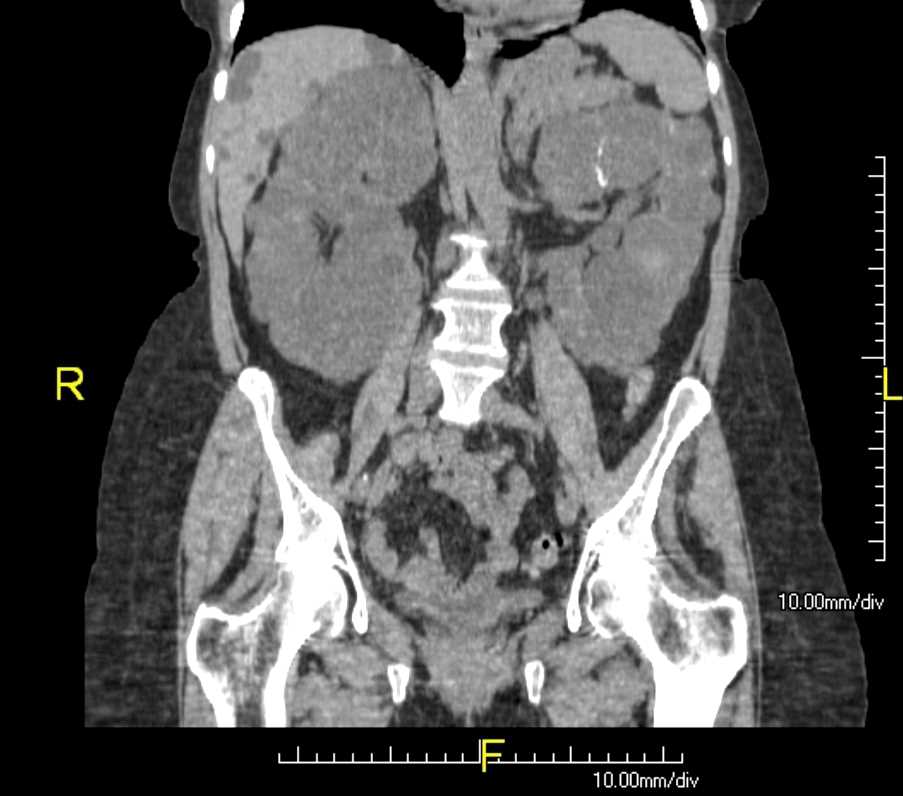

Renal cysts can be diagnosed by ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging scans (MRI).

Infantile polycystic kidney disease is usually first evaluated with ultrasound in utero.[2] The mother usually presents with oligohydramnios from the poor renal function of the fetus. After birth, an ultrasound is performed that will show enlarged kidneys with numerous small renal cysts bilaterally.[2] The kidneys can be further evaluated with an MRI, which normally shows a diffuse increase in the T2 signal.[2]

Multicystic dysplastic kidney disease is usually evaluated in utero versus early in neonates and presents as multiple non-communicating renal cysts.[15][16]

Adult polycystic kidney disease is often evaluated with ultrasound or CT. The classification of more than two cysts per side by the age of 30 helps in the diagnosis but is not definitive.[8]

Obstructive cystic renal dysplasia is typically diagnosed in utero, demonstrating a normal to small kidney size of the affected kidney with multiple scattered cysts.[17][18][19][20]

Ultrasound evaluation of a renal cyst can be described as simple or complex. A simple renal cyst has a well-marginated anechoic lesion with possible posterior acoustic enhancement. A minimally complex cyst may demonstrate a few septations. A complex cyst will demonstrate thick septations or walls and can have a hypoechoic appearance, signs of internal debris, or demonstrate enhancement after IV contrast infusion.

A simple cyst on MRI will demonstrate a low T1 signal and a high T2 signal, with no evidence of enhancement post-contrast.[13]

Bosniak Classification of Renal Cysts

The Bosniak classification system is used to stratify renal cysts and cystic masses according to their risk of malignancy.[13] If more than 25% of the lesion is solid, then it's considered a malignant cystic mass and handled accordingly.[13] Radiology will usually provide a Bosniak score in their report regarding any renal cystic structure. If not, ask them for it.

- Bosniak I describes lesions that are simple round cysts with imperceptible walls. No follow-up is needed, and there is a less than 1% chance of malignancy.

- Bosniak II lesions demonstrate minimal complexity with a few thin septations less than 1 mm in thickness, thin or small calcifications, and/or demonstrate a highly attenuated lesion less than 3 cm in diameter without contrast enhancement. Bosniak II lesions also require no follow-up and have a less than 1% chance of malignancy.

- Bosniak IIF lesions have minimal complexity, an increased number of thin septations with possible "perceived" or mild enhancement that is not measurable (<10 Hounsfield units), or a highly attenuated lesion larger than 3 cm. These lesions require follow-up with CT or ultrasound. Repeat cross-sectional imaging with IV contrast is recommended by most experts approximately 6 and 12 months after initial diagnosis and then annually for 5 years if there is no progression. If the lesions grow in size and develop internally enhancing soft tissue, they become category III lesions and require surgical treatment or ablation therapy. (The "F" stands for "Follow-up.") A Bosniak IIF lesion has a 5% chance of malignancy. Bosniak IIF or higher lesions should generally be managed and followed by urology.

- Bosniak III lesions are indeterminant in appearance in imaging studies, with thick septations and possible nodularity. They may also demonstrate measurable wall enhancement with IV contrast greater than ten Hounsfield units on CT. The recommended treatment is a biopsy and partial nephrectomy versus percutaneous microwave therapy or cryoablation. Bosniak III lesions have a 55% chance of malignancy.

- Bosniak IV lesions describe a solid mass with cystic versus necrotic components. These are considered almost unquestionably malignant. The recommended treatment is partial or total nephrectomy. Bosniak IV lesions have virtually a 100% chance of being cancerous.

Treatment / Management

Infantile polycystic kidney disease treatment is mostly supportive, with dialysis and transplant, but overall, patients tend to have a poor prognosis. See our companion StatPearls reference article on "Polycystic Kidney Disease of Childhood."[2]

Multicystic dysplastic kidney disease has a controversial treatment of nephrectomy of the affected side.[15][16] If a nephrectomy is not immediately performed, close follow-up is recommended because there is a low risk of malignant transformation.[15][16] Patients typically have a normal life expectancy as long as the contralateral kidney has normal function.[16]

Adult polycystic kidney disease is the leading inherited cause of end-stage kidney disease and results in the requirement of dialysis and transplant in the vast majority of cases by middle age through the early 60s.[8] See our companion StatPearls reference article on "Polycystic Kidney Disease."[8]

Removal of the obstruction effectively treats obstructive cystic renal dysplasia.

Differential Diagnosis

If the patient presents with a symptomatic renal cyst, which may include abdominal pain or urinary obstruction, then the differential is broad. Given that the kidneys are bilateral structures, almost every organ can be implicated in pain caused by a renal cyst. It is worth noting, however, that most renal cysts are asymptomatic and are most commonly found incidentally. The differential diagnosis for a symptomatic cyst includes, but is not limited to:

- Adrenal neoplasm

- Gallbladder disease

- Hernia

- Kidney stones

- Pyelonephritis

- Renal neoplasm

- Splenic infarction

- Trauma

Prognosis

The prognosis of renal cysts varies widely with their etiology. Simple Bosniak type I cysts have a minimal chance of malignancy, whereas Bosniak type IV cysts are almost certain to be associated with a renal cancer.[13]

In recessive (pediatric) polycystic kidney disease, approximately 30% of patients will not survive their first week of life, and patients surviving beyond that will require lifelong dialysis or kidney transplant while also often having cystic liver disease.[2]

Dominant (adult) polycystic kidney disease has a variable onset, but if it progresses to end-stage renal failure, then the patient will require dialysis or a kidney transplant.[8]

Complications

The prognosis of renal cysts and the complications that can occur secondary to them and their treatment varies widely based on the etiology, nature, location, and characteristics of the cyst.

Bosniak type I cysts can be safely observed and thus pose no risk of complication, whereas Bosniak type IV cysts will require surgery that is accompanied by a significant risk of complications such as damage to surrounding structures like the liver, spleen, or stomach.[13]

Patients with recessive (pediatric) polycystic kidney disease that survive their first few weeks of life will require lifelong dialysis or kidney transplant, as will patients with dominant (adult) polycystic kidney disease who progress to end-stage renal failure.[21][22]

Dialysis can be complicated by infections or damage to vascular structures.[22][23]

Patients who receive transplants are at higher risk for infections due to immunosuppression, transplant rejection, as well as the complication profile that accompanies the major surgery entailed during a transplantation procedure.[24][25]

Deterrence and Patient Education

While there is no way to deter the formation of renal cysts, it is important to educate patients who develop or inherit them about the nature of these lesions.

Patients with incidentally found Bosniak type I or II cysts should be reassured there is a minimal to no chance of malignancy, and no scheduled follow-up is required.[13]

Patients with Bosniak type IIF cysts should be educated about the need for them to have regular imaging studies and attend their follow-up visits to ensure the cyst is not progressing.[13]

Patients with Bosniak type III or IV cysts should be educated about their significant risk of malignancy, and a long-term care plan should be established both for the surgical management of their complex cyst and for their postoperative care.[13]

The parents of patients with recessive (pediatric) polycystic kidney disease should be educated on their child's lifelong need for dialysis as well as the possibility of a kidney transplant in the future.[2]

Likewise, patients with dominant (adult) polycystic kidney disease who progress to end-stage renal failure should be informed about dialysis as well as the possibility of a future kidney transplant.[8]

Pearls and Other Issues

The most common associated disease with infantile polycystic kidney disease is Caroli disease of the liver and hepatic fibrosis.[2]

There are many associated findings of adult polycystic kidney disease, including berry aneurysms, hypertension, liver cysts, and cysts within different organs.[8]

There is an association between VACTERAL (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb abnormalities) and congenital heart disease with obstructive cystic renal dysplasia.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of renal cysts is best done with an interprofessional team that includes a urologist, nephrologist, geneticist, pediatric urologist, and a primary clinician with the assistance of a nurse practitioner or physician assistant.

Hereditary cysts are progressive and may eventually affect renal function. Thus, these patients have to be monitored for life. For those without symptoms, the management is supportive. When renal function declines, end-stage renal disease is a possibility, and the nephrologist should be involved early in the care of these patients.

The nurse can answer questions and help educate the patient on options for dialysis and renal transplant. Unfortunately, patients with genetic cystic disorders also typically have other organ involvement, and their prognosis is guarded.[Level 5][26][27]