Introduction

The radial artery is one of two continuations of the brachial artery, the other being the ulnar artery. It supplies the anterior compartment of the forearm. The radial and ulnar arteries originate as a bifurcation of the axillary artery in the cubital fossa and serve as the major perforators of the forearm. Following its bifurcation, the radial artery runs along the lateral aspect of the forearm between the brachioradialis and flexor carpi radialis muscles.[1] Immediately proximal to the wrist, it splits into the superficial and deep palmar branches forming an anastomosis with the distal branches of the ulnar artery in the hand. The radial artery is quite superficial. It is easily palpated proximal to the wrist crease immediately lateral to the tendon of the flexor carpi radialis muscle.

Structure and Function

Arterial walls are composed of three tissue layers:

Tunica Adventitia (Externa)

This is the outer covering of the artery. It is composed of connective tissue, collagen, and elastic fibers, which allow distension of the wall during various pressure changes.[2]

Tunica Media

It is located between the adventitia and intima. It is composed of circumferentially oriented smooth muscle and elastic fibers.

Tunica Intima

The inner layer is composed of an elastic membrane and smooth endothelium.

Embryology

The initial proposal of embryological development of the upper limb as gradual sprouting of arterial trunks from a primitive axial artery was in 1933 by Singer. In 1995, Rodriquez-Baeza et al. proposed a method in which terminal branches of the superficial arterial segments of the brachial artery form anastomotic connections with the primitive axillary artery, and regression patterns are responsible for the definitive arterial pattern.[3] Variations in these superficial branches may be responsible for anatomic variations of the axillary artery.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

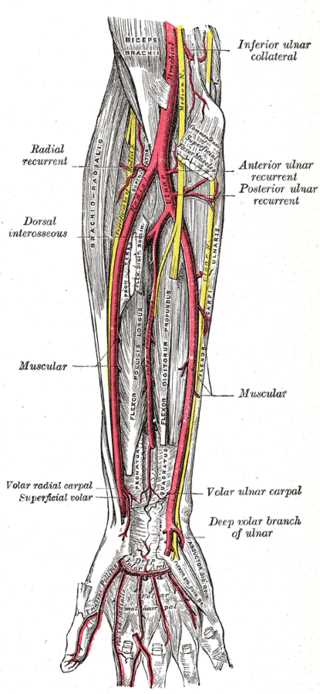

The branches of the radial artery are best organized based on their anatomical location; in the forearm, wrist, or hand. They are listed below based on their order of origination traveling distally along the upper extremity.

Forearm

Radial Recurrent artery – Originates below the origin of the radial artery, typically on its lateral aspect, and travels proximally between the branches of the radial nerve to anastomose with the radial collateral artery, a branch of the deep artery of the arm.

Muscular branches – distributed along the medial aspect of the radial artery as it travels distally and provides multiple perforators to muscles on the radial aspect of the forearm.

Palmar (volar) carpal branch – Arising near the distal aspect of the pronator quadratus. It travels across the carpal bones and anastomoses with the palmar carpal branch of the ulnar artery.

Superficial palmar branch – Originating from the medial aspect of the radial artery over the radial styloid, it travels distally to anastomose with the terminal branches of the ulnar artery to form the superficial palmar arch.

Wrist

Dorsal carpal branch – Originates distal to the radial styloid and travels superficially over the scaphoid and anastomosis with the ulnar dorsal carpal branches to form the dorsal carpal arch.

First dorsal metacarpal artery – Arises at the level of the first metacarpal as the radial artery enters the palmar aspect of the hands to form the deep palmar arch. It is composed of two arteries that supply the medial aspect of the first digit and the lateral aspect of the second digit.

Hand

Princeps pollicis artery (principal artery of the thumb) – Arises as the radial artery travels medially. It supplies the lateral aspect of the thumb and the proper palmar digital arteries.

Radialis indicis artery (radial artery of the index finger) – originates near the principal artery of the thumb and runs between the heads of the first dorsal interosseous muscle to supply the lateral aspect of the index finger. Occasionally an anatomical variant may be present in which the radialis indicis arises from the princeps pollicis artery.

Deep palmar arch – The deep palmar arterial arch is formed primarily by the radial artery. It lies across the bases of the metacarpals. The deep palmar arterial arch arises from the princeps pollicis, radialis indicis, and three palmar metacarpal arteries. It terminates by anastomosing with the superficial palmar arterial arch.

Nerves

Because the sympathetic nervous system supplies the peripheral blood vessels, the radial artery is supplied by sympathetic nerves. It is supplied primarily by the sympathetic branches of the C6 nerve root, although the hand can also be supplied by C7 on the radial side. Note that this terminology of the autonomics having a sensory function is a contradiction in terms, as the sympathetic nervous system, like the autonomics in general, is defined as a two-neuron general visceral efferent (motor) system. In reality, the sympathetics also carry visceral sensory fibers as well. Note, for example, the sympathetics through the cardiac nerves supply the sensory innervation of the heart, although some authorities believe the base of the heart may carry vagal sensory innervation as well. This concept of vagal innervation has been used to explain the precordial pain (sympathetic) radiating into the neck (vagus) observed in angina pectoris.

Muscles

The radial artery supplies the posterolateral aspect of the forearm as well as vascular territories, including the elbow joint, carpal bones, thumb, and lateral index finger. It passes beneath the brachioradialis. In the distal forearm, the brachioradialis narrows to its insertion on the styloid process of the radius. The radial artery then travels in the anatomical snuffbox (la tabatiere anatomique de Cloquet) to pass between the two heads of the first dorsal interosseus muscle.

Physiologic Variants

The radial artery commonly occurs as a bifurcation in the antecubital fossa at the level of the radial neck and continues distally in the anterior forearm. Literature has documented that the brachial artery has multiple physiologic variants. These include a high origin from the axillary artery or the brachial artery, under the pronator teres, or in some patients, a congenital absence.[4][5][6]

Rodríguez-Niedenführ et al. refer to multiple terms used to refer to the concept of "high bifurcation." [4] Haladaj et al. reported the previous nomenclature for high bifurcation included: a double brachial artery, high bifurcation of the brachial artery, and the continuance of the superficial brachial artery as the radial artery. Haladaj et al. propose the term "brachial radial artery" to mean "high origin of the radial artery." A high origin of the radial artery was present in 9.2% of 120 cadavers; 18.1 % originated in the axillary cavity, and the remaining 81.8% in the medial bicipital groove.[7]

The radial artery will sometimes lie superficial in the forearm rather than passing beneath the brachioradialis. This can be a source of injury if a caustic compound is infused into the artery by a physician who believes that the artery is the cephalic vein. It is imperative to palpate a blood vessel to ensure that it is a vein rather than an abnormally-placed artery. A superficial ulnar artery can also be present in some individuals.

Surgical Considerations

Radial Artery Laceration: Repair vs. Ligation

In 2015 Janice et al. compared operative to nonoperative approaches to forearm lacerations discovering that penetrating injury to the forearm must address limb-threatening ischemia. In this setting, the restoration of blood flow via surgical management is necessary.[8] Given the rich anastomotic connections in the hand between the radial and ulnar arteries, isolated laceration of either artery is not typically critical. In the presence of poor hemostasis, it is safe and acceptable to ligate a distal forearm artery as long as adequate perfusion exists at the palmar arch.[8] Surgical repair is necessary for complex lacerations involving both the radial and ulnar arteries.[8] It has been established that the magnitude of concomitant nerve injury, not arterial injury, is responsible for functional disability.[9]

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG)

Leonard et al. compared the efficiency of the radial artery and saphenous vein placement in the setting of CABG. Surgeons can use the radial artery as a conduit for CABG with excellent clinical outcomes.[10] Debs et al. showed the frequency of functional graft occlusion in radial arteries was 12.0% vs. 19.7% in saphenous vein placement.[11] Additionally, the incidence of complete graft occlusion in radial artery grafts was 8.9% vs. 18.6% in saphenous vein placement.[11]

Arteriovenous (AV) Fistulas

The radial artery has long been used as a site for creating an arteriovenous fistula for dialysis. A paper by Jennings et al. reported that the proximal radial artery provided an excellent site for low-risk of dialysis-related steal syndrome.[12] While it has been recommended to create AV fistulas as far distal in the upper extremity as possible, Wu et al. documented low to moderate primary failure of proximal radial artery arteriovenous fistulas (PEAAVF) when selected as the primary site of PRAAVF formation; primary failure rate reached 12.3%.[13]

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Carpal tunnel syndrome is commonly due to an abnormality of the transverse carpal ligament, leading to median nerve compression. Other causes include diabetes mellitus, tumors, and ganglia. With an incidence of less than 3%, an aberrant radial artery may lead to carpal tunnel syndrome.[14] When present, an aberrant radial artery arises from the main radial artery that terminates at the wrist in the superficial palmar arch.[15] Carpal tunnel syndrome also occurs in pregnancy and overuse syndromes.

Clinical Significance

Pulse

Palpation for the radial artery proximal to the wrist crease and immediately lateral to the tendon of the flexor carpi radialis muscle is a common site for medical professionals to document a patient’s pulse. Additionally, it can be palpated in the anatomical snuffbox as it crosses the lateral aspect of the wrist. The medial aspect of the snuffbox is the tendon of the extensor pollicis longus muscle. The lateral aspects are the tendons of the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus muscles.[16]. Because the ulnar artery is often not readily palpable, one may find it necessary to palpate the brachial artery if the radial pulse is inadequate.

Allen Test/Modified Allen Test

The Allen test, first described by Edgar Van Nuys Allen in 1929, is a medical test to determine the arterial blood flow to the hand. An alternative method, the modified Allen test, proposed by Irving Wright, is considered superior. The hand receives blood supply from both the radial and ulnar arteries, which forms an anastomosis in the hand. Therefore, if one supply is inadequate, the other can help ensure proper profusion to intrinsic hand muscles. Below is the technique for performing the modified Allen test.

The patient is asked to keep the arm flexed at the wrist. Next, they are asked first to clench their fist tightly or to open and close their hand repeatedly and then clench. The examiner then compresses the radial and ulnar arteries, simultaneously stopping blood flow to the hand. The elbow is then extended fully, avoiding overextension as it may lead to a false positive. The fist is then unclenched, and the hand should appear white. At this point, compression gets released from the ulnar artery, and the examiner observes the hand color. Hand color should return within 10 seconds. The test is repeated, with compression removed from the radial rather than the ulnar artery.

Color is restored promptly in patients with proper arterial supply to the hand. Those with a compromised flow from either artery will have prolonged pallor following the release of arterial compression; this occurs secondary to an occlusion of the artery being released, continually reducing flow.

The modified Allen test is usable as a diagnostic tool to ensure proper arterial blood flow in patients undergoing vascular access or surgery in the hand. These procedures include arterial blood gases, cannulation, catheterization, or radial artery graft selection. In a suitable patient, the radial artery can make an ideal source for a coronary bypass procedure graft due to its size. Before any of these procedures, an Allen test/modified Allen test allows healthcare workers to determine if patients are at risk of developing hand ischemia. The Allen test/modified Allen test can also be used to determine whether ligation of the radial artery can be performed under emergent circumstances. When the radial artery has been nicked or cut, the optimal procedure is to re-anastomose the cut ends. However, under emergent circumstances, when a vascular surgeon is unavailable, one can ligate the cut ends of the artery and perform the Allen test/modified Allen test. The ulnar artery will be intact, so the medial fingers should readily blush (pink up). The issue concerns whether the thumb (princeps pollicis) and index finger (radlialis indicis) are sufficiently open to allow them to receive an adequate retrograde blood flow to permit them to survive. Another option should be sought if the index finger and thumb remain blanched (whitened).

Arteriolar Constriction in a Cold Environment

In a cold environment, the arterioles of the arteries supplying the hand contract under the influence of norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and epinephrine (adrenaline). These act on the alpha-one receptors of the arterioles to cause arteriolar constriction. This is a valuable adaptation to prevent excessive heat loss from the fingers and toes. However, in more extreme environments, this process can lead to the loss of fingers and toes due to gangrene from frostbite.

Fracture of the Scaphoid

Through its dorsal carpal branch, the radial artery supplies the scaphoid bone, which can be fractured by a fall on the outstretched hand. The loss of bone mass with age makes this fracture more common in senior citizens, who also may have a tendency to fall. If the scaphoid is fractured, it is imperative to diagnose the fracture of the scaphoid and splint the wrist. A complication is that the fracture may not show up on a radiograph for as much as a week to ten days when the bone has degenerated enough for the fracture to be visible. A scaphoid fracture can be diagnosed by putting manual pressure on the scaphoid at the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb in the anatomical snuffbox. Pain will be elicited by this maneuver if the scaphoid is fractured. If the wrist is not splinted in the case of a scaphoid fracture, the fractured portion may lose its blood supply and form a permanent non-union of the fracture. The fractured bone will become avascularized, undergoing degeneration which can be a permanent source of pain and disability.