Introduction

The pudendal nerve carries motor and sensory axons from the ventral rami of the sacral spinal nerves S2-S4 (see Image. Pudendal Nerve).[1] The nerve is paired, which is found bilaterally, 1 on the left and 1 on the right side of the body. The left and right pudendal nerves give off branches, innervating regions of the rectal canal, anus, perineum, and external genitalia. Interestingly, due to the regions it innervates, the nerve’s name is originally derived from the Latin word “pudendum." The nerve is important for carrying sensations from the clitoris and penis, labia minora, vaginal vestibule, the lower one-fifth of the vaginal canal, and the posterior aspects of the labia majora and scrotum. It is involved in controlling somatic muscles involved in penile and clitoral erection and in ejaculation in males. Additionally, this nerve innervates the external anal and external urethral sphincters. Based on its location, the nerve can be susceptible to injury, most notably during childbirth. Pudendal nerve injuries can result in loss of sensation in the nerve's distribution, fecal and urinary incontinence, and sexual dysfunction.[1]

Structure and Function

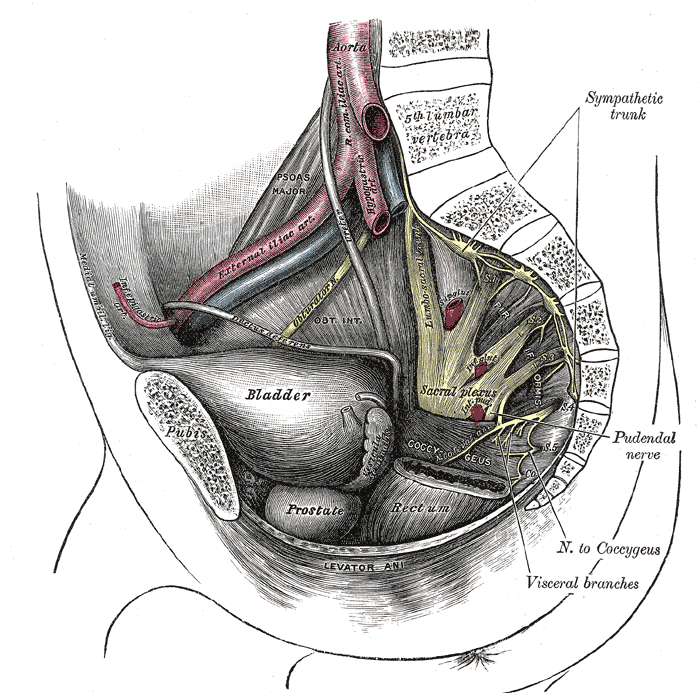

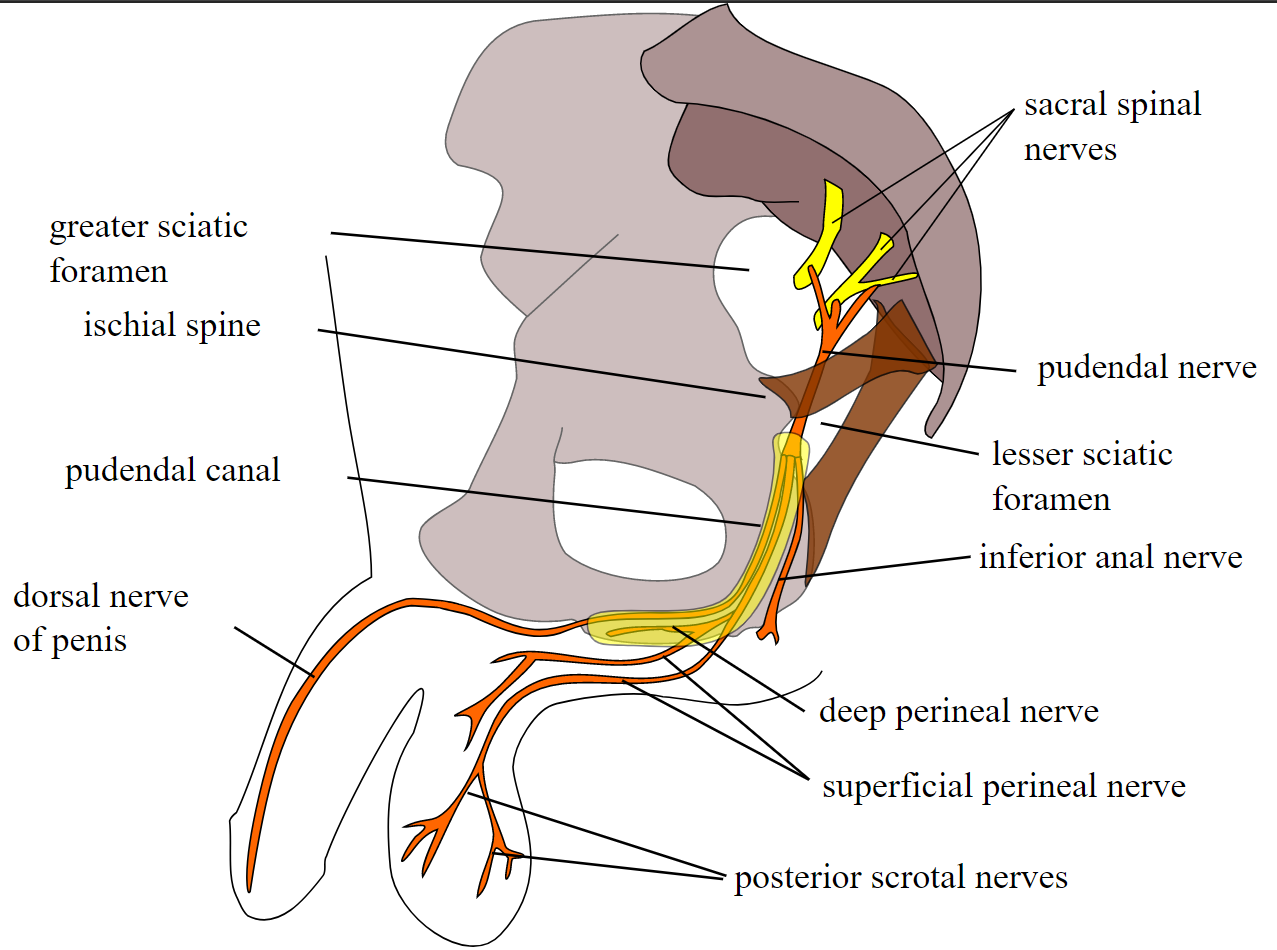

The pudendal nerve consists of 3 ventral rami from S2-S4 of the sacral plexus that converge to form the nerve adjacent to the lateral wall of the pelvic cavity. Throughout most of its path, the nerve is closely associated with the internal pudendal artery and vein branches. (Note: Although there is an internal pudendal artery and vein, there is no internal pudendal nerve.) Just after forming, the pudendal nerve exits the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle and bends around the posterior aspect of the sacrospinous ligament (see Image. Nerves and Blood Vessels in the Pelvis). It courses for a short distance within the gluteal region and bends around the sacrospinous ligament to enter the perineum through the lesser sciatic foramen. In the gluteal region, the pudendal nerve is proximal to the ischial spine, where it targets a pudendal nerve block, a technique to reduce pain associated with labor (see Image. Pudendal Nerve Block). After exiting the lesser sciatic foramen and entering the perineum, the nerve passes through a sheath of connective tissue on the medial wall of the obturator internus muscle called the pudendal (Alcock’s) canal. It continues to course through the pudendal canal, giving off 3 consecutive branches on its path toward the pubic symphysis: the inferior rectal (anal) nerve, the perineal nerve, and the dorsal nerve of the penis or clitoris.[1]

Inferior Rectal (Anal) Nerve

Within the pudendal canal, the pudendal nerve gives off its first branch, the inferior rectal nerve, that courses medially through the fat within the ischioanal fossa. This nerve carries somatic motor fibers to the external anal sphincter and carries sensations back from the anal canal, inferior to the pectinate line.[2] The somatic motor fibers are distributed to the various parts of the external anal sphincter. The innervation of the external anal sphincter allows for the voluntary control of defecation. Damage to this branch of the pudendal nerve can result in fecal incontinence. The sensory fibers of the inferior rectal nerve innervate the anal canal below the pectinate (Dentate) line, carrying the sharply defined somatic sensations from the distal portion of the anal canal. This branch of the pudendal nerve carries the pain associated with external hemorrhoids. (Sensations superior to the pectinate line are dull and visceral and are carried by the autonomic nervous system.) Except for the anal verge (which is the S5 dermatome), it also carries somatic sensations from the skin adjacent to the anus.

Perineal Nerve

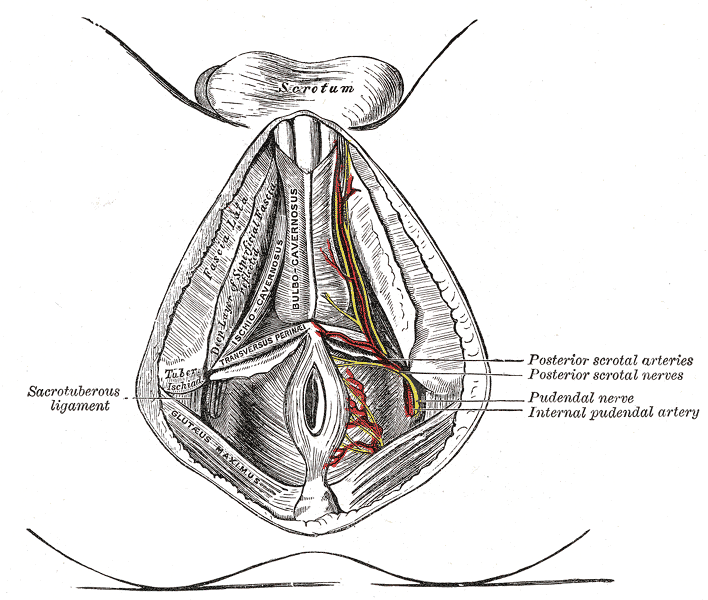

As the pudendal nerve exits the pudendal canal, a second branch diverges, which is called the perineal nerve (see Image. Perineal Arteries and Nerves, Male Perineum). This branch further divides into the deep (muscular) and superficial (cutaneous) perineal nerves. These supply motor and sensory fibers to the structures in the urogenital triangle, including the external urethral sphincter, the posterior scrotum in males, and the labia minora, vaginal vestibule, lower one-fifth of the vaginal canal, and the posterior aspect of the labia majora and in females.[2]

Motor control: In either sex, the deep (muscular) branch of the perineal nerve innervates the skeletal muscles of the superficial perineal space (pouch), ie, the ischiocavernosus, superficial transverse perineal and bulbospongiosus muscles. In males, the contraction of the bulbospongiosus muscle helps expel small amounts of residual urine in the penile urethra after urination. In both sexes, the ischiocavernosus and bulbospongiosus muscles also contribute to maximal erectile rigidity. When forming an erection, these 2 muscles contract via pudendal nerve stimulation, forcing blood out of the corpora cavernosa penis/clitoris and the bulb of the corpus spongiosum in males and the bulbs of the vestibule in females into the body of the penis/clitoris. In addition, a small slip of the bulbospongiosus muscle arches over the proximal shaft of the penis/clitoris and compresses the deep dorsal vein, which restricts venous drainage from the erectile tissues. This reduction of venous return increases intracavernous pressure.[3] Exercise stimulating these muscles can be an effective treatment for erectile dysfunction in many males.[4] This branch of the pudendal nerve is also responsible for ejaculation in males. Stimulation of the pudendal nerve causes coordinated contractions of all the perineal muscles and pelvic diaphragm (via neural connections within the lumbosacral spinal cord), with the rhythmic contractions of the bulbospongiosus muscles responsible for propelling semen through the penile urethra.[5]

In either sex, while in the deep perineal space (pouch), the deep perineal nerve innervates the 2 deep, transverse perineal muscles and, more importantly, the external urethral sphincter, allowing for the voluntary control of micturition. Damage to this branch of the pudendal nerve can result in sexual dysfunction and urinary incontinence. In females, the deep perineal nerve also innervates 2 other skeletal muscles in the deep perineal space: the compressor urethrae and the sphincter urethrovaginalis. The superficial branch of the perineal nerve carries somatic sensation from most of the skin overlying the urogenital triangle and is called the posterior scrotal or labial nerve. Additionally, the superficial branch carries sensation from the labia minora and vestibule of the vagina. The deep perineal branch carries somatic sensations from all structures in the male and female superficial perineal space, ie, erectile, muscular, or glandular, as well as the lower fifth of the vaginal canal.

Dorsal Nerve of the Penis (males) or Dorsal Nerve of the Clitoris (females)

As the pudendal nerve approaches the pubic symphysis from the deep perineal space, it continues to form its terminal branch, the dorsal nerve of the penis or clitoris. This is solely a cutaneous branch of the pudendal nerve and is critical to sexual function since it brings back somatic sensations from the shaft (body) and glans of the penis or clitoris.[6] The dorsal nerve of the penis innervates the skin overlying the shaft of the penis, the prepuce, and the glans of the penis. In females, the dorsal nerve of the clitoris innervates the clitoral body and the glans. In both sexes, this nerve relays somatic sensations from these tissues.[6] This branch is also part of an important neuropathway in forming erections. Within the lumbosacral spinal cord, the dorsal nerve afferent fibers communicate with the cavernous nerves (carrying parasympathetic axons), which pierce the perineal membrane to innervate and promote the vasodilation of erectile tissue when stimulated.[7]

Physiologic Variants

As with many other nerves, it is important to note that there is considerable variation in the anatomy of the pudendal nerve and its branches (see Image. Pudendal Nerve, Course, and Branches). The size, specific pathways, structures innervated, and the number of branches are inconsistent.[8] Even studies with small numbers of cadavers regularly identify multiple variations.[8][9][10] In a portion of the population, the pudendal nerve is derived from additional contributions, including the ventral rami of S1 or S5. Additionally, the main branches of the pudendal nerve are inconsistent in their paths and structures innervated.[9] Even additional branches are often found, providing redundant innervations to structures.[10] These variations can lead to differences in how pathologies of the pudendal nerve manifest in patients.

Surgical Considerations

In surgical procedures involving the pelvic region, it is important to consider the potential for iatrogenic damage to the pudendal nerve. The risk of pudendal nerve injury is particularly important in obstetrical, perineal, and proctological procedures. Injury has been documented to have occurred in various procedures such as cesarean section, radical prostatectomy, exploratory surgeries, and procedures to remove tumors.[11][12][13] It is imperative to understand the general anatomy of the pudendal nerve and potential variations when operating in the region to prevent iatrogenic damage.

Clinical Significance

Patients with pudendal nerve damage can be identified based on their history and presenting symptoms. Typically, neuropathy is noted in the distribution of the pudendal nerve.[1] Sources of these injuries can be due to pelvic trauma, childbirth complications, chronic irritation, or even iatrogenic injuries from radiotherapy or surgical procedures in the pelvic region.[1][12][14] Other symptoms include chronic pain, numbness, sexual dysfunction, and fecal/urinary incontinence. Injuries to the pudendal nerve can occur during childbirth. Due to the pathway of the pudendal nerve, it is vulnerable to stretch injuries during labor. Mothers delivering children with above-average birth weight are particularly susceptible to these injuries. Patients may present with fecal and or urinary incontinence post-delivery.[12] In these birth-related pudendal nerve injuries, the normal function of the nerve is typically regained without intervention.[12][15]

Patients with chronic pudendal nerve irritation, usually from prolonged sitting, may develop an uncommon syndrome known as pudendal nerve entrapment or pudendal neuralgia.[16] Any form of chronic pressure near the ischial spine can induce this injury. This syndrome has been noted to occur in professional cyclists due to chronic irritation from the bicycle seat pressing the pudendal nerve against the ischial spine or the sacrospinous ligament.[1] Pudendal neuralgia usually causes bilateral perineal pain that is worse when sitting. The pain may be progressive and can result in discomfort that is relatively resistant to treatment but can be debilitating and intense in some patients.[16] The diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia is frequently delayed, and patients often go through months or years of ineffective treatments after seeing a multitude of specialists.[16] Perineal pain when sitting should be considered a typical sign of this condition. See our companion StatPearls reference topic on "Pudendal Neuralgia."[16]

A pudendal nerve block is a procedure that involves injecting a local anesthetic in the proximity of the pudendal nerve. This procedure can help diagnose pudendal nerve entrapment. It can be used for pain relief during obstetric procedures, especially during childbirth in women who are unable to undergo spinal anesthesia. The block is performed by administering a single injection adjacent to the pudendal nerve to prevent nerve conduction transiently. In these procedures, the ischial spine is used as a landmark to aid in administering the anesthetic in the correct location.[2] This is due to the proximity of the pudendal nerve to the ischial spine as it loops around the sacrospinous ligament.[2] See our companion StatPearls reference topic on "Pudendal Nerve Block."[2]