Continuing Education Activity

Ectopic pregnancy occurs when a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus, most commonly in the fallopian tube. Prompt recognition of this condition is essential, as in the United States, approximately 1% to 2% of pregnancies are affected, and an estimated 2.7% of pregnancy-related deaths are caused by ectopic pregnancy rupture. Risk factors include pelvic inflammatory disease, smoking, prior ectopic pregnancy, fallopian tube surgery, and infertility. Symptoms typically include lower abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding in early pregnancy, particularly if intrauterine pregnancy has not been confirmed.

This course explores the complexities surrounding ectopic pregnancy, including the current diagnostic challenges, differential diagnoses, preservation of fertility, provision of psychological support, and varying management approaches. This activity for healthcare professionals is designed to enhance the learner's competence in promptly recognizing ectopic pregnancies, performing the recommended evaluation, and implementing an appropriate interprofessional management approach to improve patient outcomes.

Objectives:

Differentiate ectopic pregnancy from conditions with similar clinical features.

Interpret diagnostic studies accurately in the evaluation of ectopic pregnancy.

Implement the most appropriate management approach for each type of ectopic pregnancy.

Apply interprofessional team strategies to improve care coordination and outcomes for patients with an ectopic pregnancy.

Introduction

Ectopic pregnancy occurs when a fertilized egg implants outside the uterine cavity, a condition that affects approximately 1% to 2% of pregnancies in the United States. Ectopic pregnancy is a potentially life-threatening condition and accounts for 2.7% of pregnancy-related deaths.[1] Most ectopic pregnancies (approximately 97%) occur within the fallopian tube, commonly linked to underlying fallopian tube abnormalities.[2][3] Such abnormalities may result from prior infections (eg, gonorrhea or chlamydia), tubal surgeries (including sterilization), prior ectopic pregnancies, or exposure to diethylstilbestrol in utero. Additional risk factors include conception while using intrauterine devices (IUDs) or progesterone-only contraceptives.[1][4]

Although rare, ectopic pregnancies can also occur outside the fallopian tube, such as in the cervix, ovary, abdomen, uterine cornua, or cesarean scars.[5] These extratubal ectopic pregnancies are less likely to be associated with the typical risk factors or tubal pathology, making their diagnosis and management particularly challenging. Regardless of the location, early detection is critical for conservative treatment and improving outcomes.[1][4]

Ectopic pregnancy often causes lower abdominal pain, typically on one side, along with vaginal bleeding. Symptoms like dizziness, fainting, shoulder pain, or severe pelvic pain may indicate a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. However, these signs can mimic other conditions, eg, early normal intrauterine pregnancy, miscarriage, ovarian cyst rupture, or appendicitis.[1] Therefore, differentiating ectopic pregnancy from conditions with similar clinical features can be difficult, making prompt medical evaluation crucial for accurate diagnosis and treatment.[1][4]

Management primarily aims to preserve fertility, improve diagnostic accuracy, and provide psychological support. Treatment varies, depending on clinical stability, ectopic location, beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) levels, and ultrasound findings ranging from expectant management to surgical interventions. In select cases, nonsurgical treatment with methotrexate may be effective, especially when pregnancies are diagnosed early and meet specific criteria. However, medical treatment is less likely to succeed in cases involving larger masses, high β-hCG levels, or visible embryos. Advanced or ruptured cases typically require urgent surgical intervention.[1][4][6]

Etiology

Ectopic pregnancy, in essence, is the implantation of an embryo outside of the uterine cavity. Ectopic pregnancies most commonly occur in the fallopian tube (see Image. Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy); however, they may also develop within cesarean scars, the endocervical canal (see Image. Cervical Ectopic Pregnancy), the ovary, and the peritoneal cavity. Within the fallopian tube, ectopics most frequently are located at the ampulla region (70%), but may occur anywhere along the length of the tube, eg, the cornua (interstitial ectopic), fimbriae, or proximal segment (isthmic ectopic).[2] An ectopic pregnancy may also occur concomitantly with a normally developing pregnancy in the endometrial cavity, known as a heterotopic pregnancy.[4]

For a tubal ectopic pregnancy, various underlying pathologies can lead to damage to the fallopian tubes, inducing tubal dysfunction, which can result in retention of an oocyte or embryo within the tube. Additionally, women with tubal ligation or other postsurgical alterations to their fallopian tubes are at risk for ectopic pregnancies due to alteration of the native function of the fallopian tube. Conversely, atypical ectopic pregnancies secondary to extratubal implantations may not result from tubal dysfunction or be associated with typical risk factors.[2]

Ectopic Pregnancy Risk Factors

Factors associated with an increased risk of ectopic pregnancy include:

- Prior ectopic pregnancy: Risk increases with previous ectopic pregnancies (10% after 1, >25% after 2 or more)

- Fallopian tube damage: Due to infections (gonorrhea, chlamydia), prior pelvic or tubal surgery, or endometriosis

- Pelvic infections: Including pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and complications from ascending infections.

- Infertility and assisted reproductive technology: Higher risk with increased embryo transfers, fresh (versus frozen) transfers, and cleavage-stage (Day 3) transfers

- Contraceptive use: Although IUD users have a lower overall pregnancy risk, 53% of pregnancies occurring with an IUD are ectopic

- Smoking: Associated with increased risk due to its impact on tubal function

- Advanced maternal age: Women older than 35 have a higher risk

- Anatomical variations: Congenital anomalies of the reproductive system may contribute

- Previous cesarean delivery: Particularly in cases of prior breech presentation deliveries

- Progesterone-only contraception: Slightly increased risk compared to other methods [1][4][7][2][5]

Conversely, oral contraceptives, prior pregnancy termination, emergency contraception failure, and cesarean delivery are not associated with an increased risk of ectopic pregnancy.[4]

Epidemiology

Ectopic pregnancy accounts for approximately 1% to 2% of pregnancies in the United States and 2% to 5% among patients who have utilized assisted reproductive technology.[1][8] Emergency departments have reported a higher incidence of 6% to 16%.[7] However, the true prevalence may be underestimated due to cases managed outside hospital settings.[1] While the mortality rate from ruptured ectopic pregnancies has declined over the past few decades, they still contribute to pregnancy-related deaths.

Furthermore, the various sites where ectopic pregnancy occurs have different incidences. Tubal ectopic pregnancies are the most common, with rupture rates around 15% in Western countries, a figure that may have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.[8] Cervical ectopic pregnancy has an incidence of <1% and has been reported to occur following dilation and curettage in 70% of these patients. Ectopic pregnancies within the ovary occur in <3% of cases, while abdominal implantation occurs in 0.9% to 1.4% of cases.[4] Abdominal pregnancies have a higher mortality than other types of ectopic pregnancy at 10%; however, due to a higher frequency of delayed diagnosis and up to 7 times higher risk of organ perforation and massive hemorrhage.[4] Interstitial ectopic pregnancies are reported in up to 4% of all ectopic implantation sites. Reports also exist of implantation sites in omental, retroperitoneal, splenic, and hepatic locations.[4][8]

Additionally, the growing rate of cesarean deliveries, currently 21% of births worldwide, may contribute to an increase in cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies, which has an incidence of approximately <1%.[5][4] The incidence of heterotopic pregnancies, where both intrauterine and ectopic pregnancies occur simultaneously, has risen due to assisted reproductive technologies, with in vitro fertilization increasing the likelihood of ectopic implantation.[8] The risk of developing a heterotopic pregnancy has been estimated as high as 1:100 in women seeking in vitro fertilization.[8] Ectopic pregnancies occur in 2.1% to 8.6% of in vitro fertilization conceptions, compared to around 2% in natural pregnancies.[4]

Pathophysiology

Smooth muscle contraction and ciliary beat within the fallopian tubes assist with the transport of an oocyte or embryo to the uterine cavity. For a tubal ectopic pregnancy, damage to the fallopian tubes, usually secondary to inflammation, induces tubal dysfunction, which can result in the retention of an oocyte or embryo within the tube. Several local factors can induce inflammation, including toxic, infectious, immunologic, and hormonal etiologies.[8]

An upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines occurs following tubal damage; this subsequently promotes embryo implantation, invasion, and angiogenesis within the fallopian tube.[8] Chlamydia trachomatis infection results in the production of interleukin 1 by tubal epithelial cells; this is a vital indicator for embryo implantation within the endometrium.[8] Interleukin 1 also has a role in downstream neutrophil recruitment, which would further contribute to fallopian tubal damage.[8] Cilia beat frequency is also negatively affected by smoking and infection. Hormonal variations throughout the menstrual cycle additionally have demonstrated effects on cilia beat frequency.[8]

Histopathology

The most common site for ectopic pregnancy adherence is in the ampullary region of the fallopian tube.[8] Reportedly, 95% of ectopic pregnancies develop in the ampulla, infundibular, and isthmic portions of the fallopian tubes.[9] Villus-like structures, trophoblasts, or an embryo in the fallopian tube or other ectopic sites on histological examination are diagnostic of ectopic pregnancy.[10]

In ovarian ectopic pregnancy cases, Spiegelberg histology criteria are frequently used to differentiate this type of ectopic pregnancy from other ectopic locations.[11] Spiegelberg's criteria include the 4 following findings:

- An intact fallopian tube distinct from the ovary on the side of the ectopic pregnancy

- A gestational sac replacing the ovary's position

- The ovary containing the gestational sac is connected to the uterus by the ovarian ligament

- The specimen has ovarian tissue attached to and within the wall of the gestational sac [11]

With cesarean scar pregnancies, a migration of blastocyst into the myometrium is noted due to residual scarring defects from prior cesarean deliveries.[12] Histological findings of cesarean pregnancy included myometrial or scar tissue villous invasion with minimal decidua.[5] The depth of implantation determines the type of cesarean scar pregnancy, with type 1 having proximity to the uterine wall and type 2 implanting closer to the urinary bladder.[12]

History and Physical

Clinical History

Ectopic pregnancies within the adnexa typically present with variable pain that typically starts as colicky abdominal or pelvic discomfort, often localized to one side, though clinicians should be aware that not all ectopic pregnancies have this characteristic presentation. For tubal ectopic pregnancies, as the fallopian tube distends, the pain may become more generalized if rupture and hemoperitoneum occur. Additional symptoms can include dizziness, fainting, nausea and vomiting, shoulder pain, urinary symptoms, or rectal pressure.[1] Therefore, women of childbearing age presenting with these symptoms should be evaluated.[6] Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies can range from asymptomatic presentations during routine obstetrical ultrasound to uterine rupture.[5]

Clinicians should also identify the patient's last menstrual period and whether they have monthly routine menstrual periods. A missed last period, abnormal uterine bleeding, or sexual activity are suggestive of a possible pregnancy and, therefore, are also indications for further testing with a pregnancy test.[6] Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy should also be obtained in the clinical history.[13]

Physical Examination

After obtaining a thorough history, an attentive physical exam should be performed to help guide further diagnostic testing. Evaluation of vital signs for tachycardia and hypotension is pivotal in determining the patient's hemodynamic stability.[1] When examining the abdomen and suprapubic regions, attention should focus on the location of tenderness and any exacerbating factors. If voluntary or involuntary guarding of the abdominal musculature is elicited on palpation, possible free fluid suggestive of ruptured ectopic or peritonitis etiologies should be considered.[6]

Palpating a gravid uterus may suggest an intrauterine pregnancy; however, this does not exclude an ectopic or heterotopic pregnancy. Vaginal bleeding should be assessed with a pelvic examination in addition to evaluating for cervical abnormalities, cervical os dilation, visible products of conception, and signs of infection. Bimanual pelvic exams additionally allow for palpation of bilateral adnexa to assess for abnormal masses or elicit adnexal tenderness.[1]

Evaluation

Diagnostic Evaluation of Ectopic Pregnancy

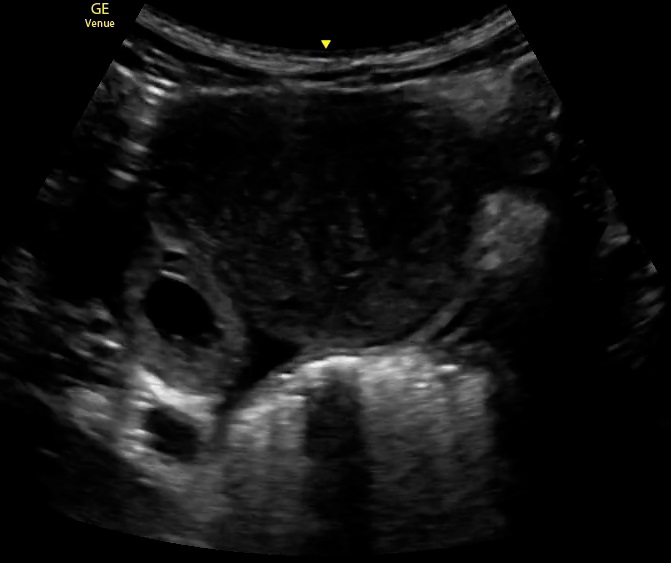

The diagnostic evaluation of ectopic pregnancy primarily relies on the assessment of serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) levels in conjunction with imaging modalities such as transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and transabdominal ultrasonography (TAUS). Among these, TVUS has been demonstrated to be the most sensitive and accurate for early detection of ectopic pregnancy, particularly when enhanced with 3-dimensional imaging and color Doppler ultrasound (see Image. Ectopic Pregnancy).[4]

Serum β-hCG trends play a crucial role in diagnosis. The presence of a β-hCG level >2000 mIU/mL without visualization of an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) is highly suggestive of an ectopic pregnancy. The rate of β-hCG increase is also informative: in a viable IUP with an initial β-hCG level <1500 mIU/mL, a 99% likelihood of a minimum 49% rise over 48 hours is typical. A slower rise or a decrease of at least 21% over 48 hours is more indicative of miscarriage or an ectopic pregnancy. A decreasing serum β-hCG level is more suggestive of a spontaneous early pregnancy loss.[1][6] The discriminatory β-hCG level, the threshold above which an IUP should be visible on TVUS, varies based on equipment, sonographer expertise, and gestational number. Historically set between 1000 and 2000 mIU/mL, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has suggested using a cutoff of up to 3500 mIU/mL to prevent misdiagnosis and avoid unnecessary termination of a viable pregnancy.[1][6] Stable patients with a decreasing serum β-hCG in whom a possible ectopic pregnancy has not been excluded should continue to be monitored with serial β-hCG levels until undetectable.[1][6]

TVUS is the gold standard for diagnosing ectopic pregnancy, with definitive confirmation when a yolk sac or embryo is visualized outside the uterus (see Image. Ectopic Pregnancy, Ultrasound). However, many cases may not continue to develop to this point, necessitating additional diagnostic approaches, including serial β-hCG monitoring, repeat ultrasonography, and uterine aspiration. In cases where neither an IUP nor an ectopic pregnancy is identified, the pregnancy is categorized as a pregnancy of unknown location (PUL). In such cases, serial β-hCG monitoring and, in some instances, manual vacuum aspiration can help differentiate between a failing IUP and an ectopic pregnancy.[1][6]

Serial assessments using transvaginal imaging, serum hCG level measurements, or a combination of both are necessary to confirm the diagnosis. The first sign of an IUP visible on ultrasound is a small sac located eccentrically within the decidua. Often, tissue rings form around the sac, leading to its designation as the “double decidual” sign.[13] This double decidual sign typically becomes visible during the fifth week of pregnancy, as seen in abdominal ultrasound imaging. The yolk sac appears around this time but requires transvaginal ultrasound imaging for accurate identification. An embryonic pole can be seen on transvaginal imaging at approximately 6 weeks of pregnancy.[13] Uterine fibroids or a high body mass index may hinder the accuracy of ultrasound imaging in detecting an early intrauterine pregnancy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be useful in extreme cases, eg, with large obstructing uterine fibroids; however, its sensitivity and specificity require further investigation, and the potential risks associated with gadolinium contrast exposure should be carefully considered.[13]

Diagnostic Findings of Non-Fallopian Tube Pregnancies

Cervical pregnancies, once typically diagnosed in the second trimester or at the time of spontaneous abortion, can now be detected earlier through TVUS. Although no standardized treatment exists, conservative fertility-preserving management options do exist. Diagnosing ovarian pregnancies solely through TVUS imaging remains difficult due to the similarities between hemorrhagic cysts and ectopic pregnancies; therefore, histopathological confirmation based on Spiegelberg’s criteria is often required (Please refer to the Histopathology section for more information regarding Spiegelberg’s criteria).[11] Rare cases of abdominal pregnancies, which may involve implantation in the retroperitoneal space, liver, spleen, appendix, or even lung, are frequently identified only during surgical intervention. Clinical signs, eg, fetal malpresentation, oligohydramnios, and elevated maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein levels, can provide diagnostic clues.[2]

Cesarean scar pregnancies present unique diagnostic challenges. TVUS, often supplemented with color Doppler imaging, is the preferred method. Key findings include a low-lying anterior gestational sac within the hysterotomy scar, a thin or absent myometrial layer between the sac and the bladder, and a prominent vascular pattern at the scar site. Magnetic resonance imaging may also be performed to help diagnose a cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. Early detection is crucial to prevent complications such as uterine rupture and severe hemorrhage.[5]

Interstitial pregnancies present another diagnostic challenge. TVUS findings suggestive of interstitial implantation include the interstitial line sign, an eccentrically located gestational sac, and a surrounding myometrial mantle <5 mm thick. Three-dimensional sonography improves detection accuracy, while MRI can be employed for inconclusive cases. Differentiating interstitial from cornual pregnancies is vital, as interstitial ectopic pregnancies have less capacity to expand and are associated with hemoperitoneum and life-threatening hemorrhage, while some cornual pregnancies may be able to progress without resulting in spontaneous abortion but have a risk of persistent vaginal bleeding, retained placenta at delivery, and uterine rupture.[2]

Treatment / Management

Management of Ectopic Pregnancy

In general, the treatment of an ectopic pregnancy balances the management of the ectopic gestation with the aim of preserving a patient's reproductive capacity as much as possible, if desired. Therefore, interventions should be tailored to optimize the patient's preferences for future reproductive outcomes.[3] The patient's hemodynamic stability directs the initial management approach for an ectopic pregnancy. Any patient exhibiting signs of a ruptured ectopic pregnancy should be urgently transferred for surgical intervention. If the ectopic pregnancy is diagnosed early, the patient remains hemodynamically stable, and the affected fallopian tube is intact, treatment options include medical management with intramuscular methotrexate or surgical options, eg, salpingostomy (removal of the ectopic pregnancy while preserving the fallopian tube) or salpingectomy (removal of part or all of the affected fallopian tube).[3] The choice between medical and surgical management depends on clinical findings, ultrasound results, serum β-hCG levels, and patient preference.

In patients with an initial β-hCG level of <200 mIU/mL, 88% of ectopic pregnancies spontaneously resolved with expectant management. Therefore, expectant management, though seldom used, may be considered in select patients who are asymptomatic with low and declining β-hCG levels and who are accepting of the risks for tubal rupture or hemorrhage.[1][6] Medical or surgical treatment should be initiated; however, if the patient begins to have pain, persistent or increasing β-hCG levels, or begins to show signs of tubal rupture.[6][1]

Medical management

Though surgical removal of an ectopic pregnancy provides definitive treatment, fertility rates are higher in patients who have undergone medical management with methotrexate. Therefore, for appropriate candidates who desire to maintain their fertility options, methotrexate may be preferred.[3] Methotrexate, a folate antagonist that disrupts rapidly dividing cells, is the only medication used for medical management of ectopic pregnancy.[1][4] Medical management is successful in approximately 70% to 95% of patients, though the efficacy decreases as initial β-hCG levels increase.[4]

Absolute contraindications to methotrexate include:

- Hemodynamic instability

- Anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia

- Immunodeficiency

- Ruptured ectopic pregnancy

- Renal or hepatic dysfunction

- Unreliable follow-up

- Active pulmonary or peptic ulcer disease

- Breastfeeding

Relative contraindications to methotrexate include:

- Fetal cardiac activity

- Serum β-hCG levels > 5000 mIU/mL or adenxal mass > 4 cm in diameter

- Blood transfusion refusal

Before administrating methotrexate, patients should be assessed for the presence of these contraindications, including a complete blood count and metabolic panel.[4]

Methotrexate can be administered via different protocols, including single-dose, 2-dose, and multidose regimens. The single-dose protocol has the least adverse effects, while the 2-dose protocol is more effective, having a lower treatment failure rate, especially in cases with higher initial β-hCG levels. Generally, a 2-dose regimen may be preferred for medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy, especially in patients at high risk for treatment failure (eg, high β-hCG levels and large adnexal masses). The multidose regimen is less favored due a more complicated administration and follow-up protocol and a the higher risk of adverse effects. Some experts have suggested that multidose regimens may considered for ectopic pregnancy of advanced gestation or extratubal locations (eg, cervical or ovarian ectopic pregnancy).[14]

Serum β-hCG levels are measured on days 4 and 7 after methotrexate administration. A decline of at least 15% between days 4 and 7 indicates effective treatment. If this reduction does not occur, additional methotrexate or surgical intervention may be required. Weekly monitoring continues until β-hCG is undetectable, which can take up to 8 weeks. Patients should be counseled about the risk of rupture until β-hCG reaches undetectable levels and be advised to seek emergency care if symptoms worsen.[1]

Common adverse effects of methotrexate include gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain), vaginal spotting, and transient hair loss. Patients should avoid folic acid supplements, NSAIDs, alcohol, narcotics, and activities that increase rupture risk (eg, vigorous exercise and intercourse). Methotrexate dermatitis can occur with sun exposure, and patients are advised to use contraception for at least 1 ovulatory cycle posttreatment, with some experts recommending a 3-month waiting period. Studies suggest methotrexate does not negatively affect future fertility.[6][1]

Surgical management

Surgical intervention provides a higher success rate than methotrexate. The decision to proceed with the surgery is guided by various factors, including elevated β-hCG levels (typically >5,000 mIU/mL), ultrasound findings indicating an embryo with cardiac activity, and social factors that may restrict follow-up access. When methotrexate is contraindicated, or not the preferred option, laparoscopic surgery is commonly performed.[6][1]

Surgical options include salpingostomy and salpingectomy. Salpingectomy generally involves the partial or complete removal of the fallopian tube. Salpingostomy, also known as salpingotomy, entails removing the ectopic pregnancy through a tubal incision while keeping the fallopian tube intact. Both methods yield similar outcomes concerning future intrauterine pregnancy rates and the recurrence of ectopic pregnancies. The choice to remove or preserve the fallopian tube relies on intraoperative evaluation and the patient's fertility objectives. In instances of significant tubal damage, rupture, or previous tubal ligation, salpingectomy is the preferred approach. Patients with an intact contralateral fallopian tube experience comparable reproductive outcomes, whether they opt for salpingostomy or salpingectomy. For interstitial ectopic pregnancies, hysterectomy may be necessary for patients who experience severe hemorrhaging or do not wish to preserve fertility.

Cervical and Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy

Specialized approaches are required for cervical and cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies. For cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies, expectant management is not recommended due to the risk of uterine rupture and hemorrhage, except in select cases of confirmed fetal demise. Surgical options such as transvaginal or laparoscopic resection have demonstrated low complication rates. Curettage alone is not recommended due to the risk of hemorrhage and incomplete removal of trophoblastic tissue. In cases where fertility preservation is not a priority, hysterectomy may be considered.[5][2]

Medical management of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy typically involves local or intragestational methotrexate injections, often with systemic methotrexate. Systemic methotrexate alone is not recommended due to higher failure rates and complications. Ultrasound-guided aspiration may complement medical therapy. Posttreatment monitoring is essential, as β-hCG levels and mass size may take weeks to resolve.[5][2]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses to consider with ectopic pregnancies include:

- Ovarian torsion

- Tubo-ovarian abscess

- Appendicitis

- Hemorrhagic corpus luteum

- Ovarian cyst rupture

- Threatened miscarriage

- Incomplete miscarriage

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Ureteral calculi [1]

Prognosis

The prognosis for ectopic pregnancy depends on early diagnosis and timely intervention. If identified and treated before rupture, either medically with methotrexate or surgically, the risk of severe complications is significantly reduced. However, delayed diagnosis can lead to tubal rupture, resulting in life-threatening hemorrhage and hemodynamic instability. In such cases, emergency surgical intervention is required, which may involve salpingectomy, potentially impacting future fertility.[4][6]

Patients with a history of ectopic pregnancy are at increased risk for recurrence, particularly if underlying risk factors such as prior tubal surgery, pelvic inflammatory disease, or assisted reproductive technology are present. Overall, with appropriate management, most patients recover well, but long-term follow-up is important to address fertility concerns and monitor for potential recurrence.[1][15]

Complications

Complications of ectopic pregnancy include:

- Tubal rupture

- Severe hemorrhage

- Blood transfusion

- Hemodynamic shock leading to multiorgan failure

- Fertility impairment

- Recurrent ectopic pregnancy

- Adhesion formation

- Emotional and psychological distress [4][6][1][15]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and patient education play a crucial role in reducing the risk and improving early detection of ectopic pregnancy. Patients, especially those with risk factors such as a history of pelvic inflammatory disease, prior ectopic pregnancy, tubal surgery, or infertility treatments, should be educated about the symptoms and importance of early prenatal care. Emphasizing the need for timely pregnancy testing and early ultrasound evaluation can aid in the early identification of an ectopic pregnancy before complications arise. Women should be advised to seek immediate medical attention if they experience symptoms such as severe abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, dizziness, or fainting, as these could indicate a ruptured ectopic pregnancy requiring emergency care.

Clinicians should also counsel patients on modifiable risk factors, eg, smoking cessation and the prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) through safe sexual practices, as these can reduce the risk of tubal damage and future ectopic pregnancies. Patients undergoing fertility treatments or with known tubal abnormalities should be closely monitored in early pregnancy with serial β-hCG measurements and transvaginal ultrasounds to detect an ectopic pregnancy before rupture occurs. Providing emotional support and resources, including counseling services, can also help patients cope with the psychological impact of an ectopic pregnancy and any associated fertility concerns.

Patients who seek medical treatment for ectopic pregnancy may need to discuss with their obstetrician which foods, supplements, and drugs to avoid when taking methotrexate, as there may be decreased efficacy due to adverse interactions with the drug. Methotrexate may increase immunosuppression when paired with other medications, among other potential adverse effects. Patients undergoing surgical interventions must adhere to the surgeon's recommendations to limit the risk of infection and other postoperative complications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of ectopic pregnancy requires a well-coordinated, interprofessional approach to ensure accurate diagnosis, timely treatment, and optimal patient outcomes. When a woman presents to the emergency department with symptoms suggestive of an ectopic pregnancy, the healthcare team—including nurses, emergency physicians, obstetricians, advanced practitioners, and pharmacists—must work collectively to provide efficient, patient-centered care. Nurses play a critical role in the initial assessment by recognizing key symptoms and ensuring prompt evaluation by a physician. It is the responsibility of the clinician to consider ectopic pregnancy in any sexually active woman of childbearing age presenting with abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding. Evidence-based tools can enhance diagnostic accuracy and reduce unnecessary testing or delays in care. By incorporating standardized protocols and leveraging clinical decision-making models, healthcare teams can improve efficiency and enhance patient safety.

Interprofessional communication is essential in the management of ectopic pregnancy, particularly when consulting specialists such as obstetricians, radiologists, and pharmacists. Emergency physicians and obstetricians must collaborate closely to confirm the diagnosis, determine the appropriate management plan, and discuss treatment options with the patient. Pharmacists play a crucial role in ensuring the safe administration of methotrexate when medical management is appropriate, providing education on potential adverse effects, and monitoring requirements. Nurses are responsible for patient education, emotional support, and posttreatment follow-up, reinforcing adherence to care plans and recognizing potential complications. By fostering teamwork, clear communication, and adherence to established protocols, healthcare professionals can enhance patient-centered care, improve outcomes, and ensure the highest patient safety standards in managing ectopic pregnancy.