Continuing Education Activity

Porcelain gallbladder refers to the condition in which the inner gallbladder wall is encrusted with calcium. The wall becomes brittle, hard, and often takes on a bluish hue. It is usually found incidentally on plain abdominal x-rays or other imaging because most patients are asymptomatic. The extent of gallbladder wall involvement varies from the presence of a single calcified plaque adhered to the mucosal layer to total full-thickness replacement of the tissue of the entire gallbladder wall with calcium. This activity reviews the pathophysiology of porcelain gallbladder and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Review the etiology of porcelain gallbladder.

- Describe the pathophysiology of porcelain gallbladder.

- Summarize the treatment options for porcelain gallbladder.

- Review the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by porcelain gallbladder.

Introduction

Porcelain gallbladder refers to the condition in which the inner gallbladder wall is encrusted with calcium. The wall becomes brittle, hard, and often takes on a bluish hue. Other names for this condition are calcified gallbladder, calcifying cholecystitis, and cholecystopathia chronica calcarea. It is usually found incidentally on plain abdominal x-rays or other imaging because most patients are asymptomatic. The extent of gallbladder wall involvement varies from the presence of a single calcified plaque adhered to the mucosal layer to total full-thickness replacement of the tissue of the entire gallbladder wall with calcium. The latter description is the more classic finding when discussing porcelain gallbladder [1].

Porcelain gallbladder is very rare, and in the past, it was believed to be associated with gallbladder malignancy. However, the current opinion is that the risk of malignancy is small. Porcelain gallbladder is often seen in elderly females and may sometimes become obvious on a plain x-ray.

Etiology

The etiology of calcified gallbladder walls is unknown, but the mechanism is felt to be similar to gallstone development. Gallstones are usually formed from bile that is in stasis. When bile is not fully emptied from the gallbladder, it can precipitate as sludge and subsequently turn into stones. Biliary obstruction may also lead to gallstones, including bile duct strictures and cancers, such as pancreatic cancer. The most common cause of cholelithiasis is from the precipitation of cholesterol that subsequently forms into cholesterol stones. The second form of gallstones is pigmented gallstones, which are the result of increased red blood cell destruction in the intravascular system causing increased concentrations of bilirubin, which subsequently get stored in the bile. These stones are typically black. The third type of gallstones is mixed pigmented stones, which are a combination of calcium substrates such as calcium carbonate or calcium phosphate, cholesterol, and bile. The fourth type is made up primarily of calcium and usually found in patients with hypercalcemia. Concurrent findings include kidney stones. Porcelain gallbladders are also felt to be indicative of a more prolonged chronic gallbladder condition. One theory is that the gallbladder muscularis layer becomes calcified first, leading to denuding and sloughing of the now devascularized mucosa [1].[2]

Epidemiology

The incidence of porcelain gallbladder is rare and has been found in less than 1% of routine cholecystectomy specimens. There is also a female predominance of 5 to 1 over males. Older age is also a risk factor, with most occurring over the age of 60. Gallstones are present in about 95% of cases of porcelain gallbladders, therefore making the presence of gallstones a significant risk factor for the development of a calcified gallbladder wall. Most gallstones are asymptomatic, just as with calcified gallbladders. In the United States, approximately 14 million women and 6 million men with an age range of 20 to 74 have gallstones. The prevalence increases as a person ages. Obesity increases the likelihood of gallstones, especially in women, due to increases in the biliary secretion of cholesterol.

On the other hand, patients with drastic weight loss or fasting have a higher chance of gallstones secondary to biliary stasis. Furthermore, there is also a hormonal association with gallstones. Estrogen has been shown to result in an increase in bile cholesterol as well as a decrease in gallbladder contractility. Women of reproductive age or on birth control medication that have estrogen have a two-fold increase in gallstone formation compared to males. People with chronic illnesses such as diabetes also have an increase in gallstone formation as well as reduced gallbladder wall contractility due to neuropathy. The prolonged presence of gallstones and the etiologies that form gallstones is most likely a major factor in progression to calcification of the gallbladder wall. [3][4]

Pathophysiology

Gallstones occur when substances in the bile reach their limits of solubility. As bile becomes concentrated in the gallbladder, it becomes supersaturated with these substances, which in time precipitate into small crystals. These crystals, in turn, become stuck in the gallbladder mucus, resulting in gallbladder sludge. Over time, these crystals grow and form large stones. A progression of this process probably leads to calcification of the gallbladder wall to varying degrees. The relationship between calcification of the gallbladder and gallbladder cancer goes back to the 1700s. Several studies from the 1930s and 1960s showed a definite correlation between gallbladder cancer and porcelain gallbladder, with rates as high as 60%. Historically in medical school and residency, students are taught that there is a strong correlation between porcelain gallbladder and gallbladder cancer. However, newer studies appear to have debunked that notion.

More recent studies have shown the true incidence of gallbladder cancer in the presence of a calcified gallbladder wall to be around 6%. The incidence of gallbladder cancer, in general, is around 2% to 8%. Closure inspection of pathology specimens has shown that there is a higher rate of gallbladder cancer in porcelain gallbladders when there is only a partial presence of calcification adherent to an intact mucosa. There seems to be no gallbladder cancer risk in specimens when there is the replacement of the gallbladder wall with calcium, and there is no intact mucosa. The true incidence of gallbladder cancer with porcelain gallbladders is unknown because most patients with porcelain gallbladders are asymptomatic, undiagnosed, and never have cholecystectomies [3].

Histopathology

The gallbladder wall may be thickened to variable degrees, and there may be adhesions to the serosal surface. Smooth muscle hypertrophy, especially in prolonged chronic conditions, is present. Calcium bilirubinate or cholesterol stones are most often present and can vary in size from sand-like to filling the entire gallbladder lumen. They can be multiple or singular. Normal appearing bile can also be present. Various species of bacteria can be found in 11% to 30% of the cases. Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses are present 90% of the time in cholecystitis specimens.

These are a herniation of intraluminal sinuses from increased pressures possibly associated with ducts of Luschka. The mucosa will exhibit varying degrees of inflammation. The wall of the gallbladder will have either complete intramural replacement by calcium or less extensive patchy areas of adherent calcium to the intact mucosa. In cases of complete replacement of the wall by calcium, the mucosa has usually totally been denuded and sloughed off. In cases of patchy calcium infiltrates, the mucosa may exhibit an inflammatory appearance. These cases are at a higher risk of forming gallbladder cancers. Pathology will diagnose the finding of biliary cancer either as a diffuse aggressive malignancy or rarely as an isolated focus of cancer. It is felt that the development of this malignancy is caused by chronic irritation and inflammation of the gallbladder mucosa [5].

History and Physical

Most cases of porcelain gallbladder are asymptomatic. However, some patients do exhibit signs of chronic cholecystitis. Patients with chronic cholecystitis usually present with dull right upper abdominal pain that radiates to the mid back or right scapular tip. It is usually associated with fatty food ingestion. Nausea and occasional vomiting also accompany complaints of increased bloating and flatulence. Often the symptoms occur in the evening. Prolonged less acute symptoms are usually present over weeks or months. Increased frequency and severeness of acute exacerbations (acute biliary colic) is usually seen in the presence of more prolonged chronic symptoms. The classic physical examination will demonstrate right upper abdominal pain with deep palpation (Murphy's sign). If the patient is very thin or if the gallbladder is enlarged, a firm, hard gallbladder can be palpated in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Patients are usually not acutely ill but are uncomfortable. Their vital signs are often within normal parameters.[4]

Evaluation

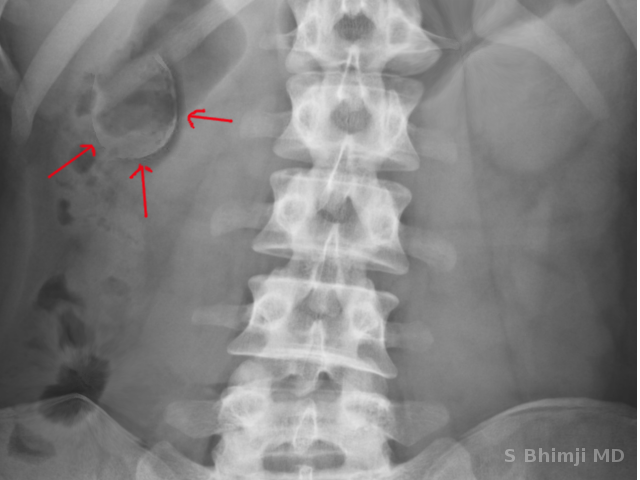

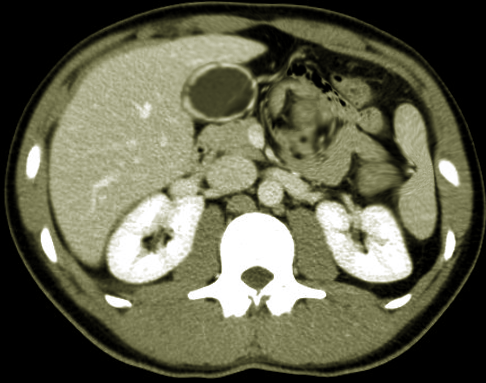

This condition is usually diagnosed incidentally by an x-ray exam, either an abdominal x-ray or a CT scan. Abdominal ultrasound and MRI can also diagnose the condition. Cases that do present with cholecystitis symptoms are often diagnosed with ultrasound. Labs are often normal.[6]

Treatment / Management

The classic treatment for porcelain gallbladders is cholecystectomy. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is most often done. However, in the past, the recommendation was to perform the cholecystectomy open due to the perceived higher incidence of gallbladder cancer. Some recent reports recommend conservative therapy with serial gallbladder ultrasounds in cases of incidental calcified gallbladders, which are asymptomatic. Most surgeons would recommend cholecystectomy [7][3].

Differential Diagnosis

Many other conditions can mimic gallbladder disease. Patients who present with acute biliary colic are often worked up for cardiac issues. Other common conditions with similar presenting symptoms are peptic ulcer disease, irritable bowel disease, inflammatory bowel disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, pulmonary embolism, and musculoskeletal disorders. Cases of asymptomatic porcelain gallbladders with palpable masses in the right upper abdomen can be misdiagnosed as abdominal hernias, lipomas, or other neoplastic growths.[8]

Prognosis

Patients with noncancerous porcelain gallbladders treated with cholecystectomies have the same very good prognosis as those who have undergone surgery for routine cholecystitis. The small percent of those in which gallbladder cancer has been found have a much worse prognosis. Survival rates, as with any cancer, are related to staging. Stage 1 gallbladder cancer patients have a 50% 5-year survival rate; stage 2 has a 28% survival rate, stages 3 and 4 have 8% and 2% survival rates.[9]

Pearls and Other Issues

Be aware that porcelain gallbladders may carry a higher rate to develop gallbladder cancer than non-porcelain gallbladders despite recent findings that suggest that the rate is lower than previously thought. Consideration for laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be given for asymptomatic patients diagnosed with porcelain gallbladders.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Porcelain gallbladder may not be difficult to recognize if the treating physician knows this condition. It is important to get a timely referral to a surgeon for appropriate treatment. The idea of a high incidence of gallbladder cancer associated with porcelain gallbladder is outdated recognition of the possibility of gallbladder cancer with this disease; however, must prompt a high level of suspicion for all involved in this patient's care. Accurate histologic diagnosis is also paramount.[10][11]