Introduction

Despite its small size, the popliteus is a major stabilizing muscle of the knee. The popliteus is involved in both the closed chain phase and open-chain phase of the gait cycle. During the closed chain phase, which is when the foot is in contact with the ground, the muscle externally rotates the femur on the tibia. In the open-chain phase or swing phase of the limb, the popliteus acts to internally rotate the tibia on the femur.[1] The popliteus is accompanied by the tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, and flexor hallucis longus forming the deep posterior compartment of the leg. It forms the base of the popliteal fossa and is the only muscle of either the deep posterior or superficial posterior fossa to act solely on the knee joint as a posterolateral stabilizer.

Often overlooked as a critical stabilizer of the knee joint, the popliteus can commonly be involved in posterolateral corner injuries of the knee. These injuries typically occur secondary to a varus force or direct blow to the knee (from medial to lateral). Diagnostic imaging of choice is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for evaluation and dysfunction. MRI can also point to other related issues within the knee. An iatrogenic popliteal injury may result in a future poor functional outcome and is critical to address, particularly following knee reconstruction surgery. Patients with anatomically smaller knees may also be at increased risk for popliteal injury.[2]

Structure and Function

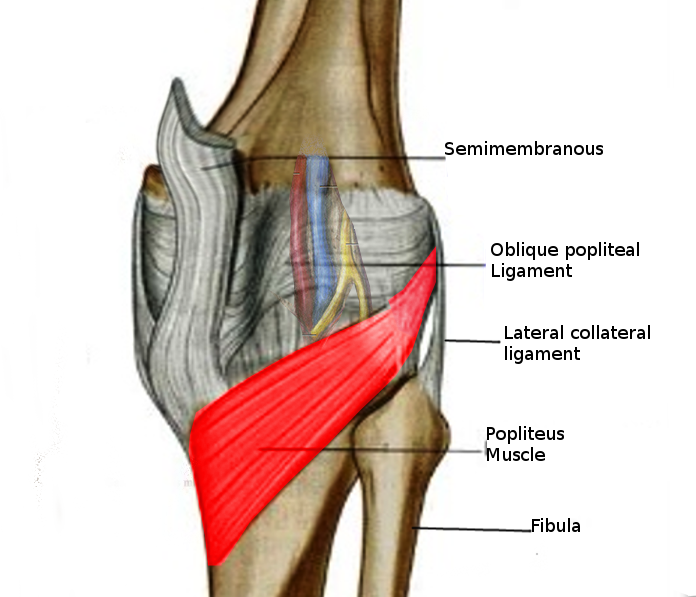

The muscle fibers of the popliteus originate from the lateral condyle of the femur and insert on the posterior surface of the tibia, superior to the soleal line. Cadaveric dissections have also revealed fibers originating from the styloid portion of the fibular head and running obliquely, blending with the main muscular structure. The popliteus is a capsular structure, although extra-articular, and separates the lateral meniscus from the lateral collateral ligament.[3][4]

The popliteus also assists in knee flexion. Its function is dependent on whether the lower extremity is in a weight-bearing or non-weight-bearing state; it is considered the primary internal rotator of the tibia in the non-weight-bearing state.[5] "Locking" the knee occurs with extension during weight-bearing. This describes the femur medially rotating on the tibia, allowing for full extension without muscular expenditure. When "unlocking" the knee, the popliteus contracts causing flexion and lateral rotation of the femur on the tibia. This is why some refer to the popliteus as the "key" to the locked knee.[1]

There are attachments between the popliteus and the lateral meniscus. When the knee motions into flexion, the popliteus retracts the lateral meniscus posteriorly to avoid becoming entrapped between the femur and tibia.[4]

Embryology

The mesoderm is the middle layer of the trilaminar disc of tissue formed as a result of gastrulation in a fetus. Surrounded by the endoderm and ectoderm, the mesoderm is the structure giving rise to connective tissue and muscles of the human body aside from the muscles of the head, which develop from neural crest tissue. Thus, the popliteus muscle originates from the mesoderm.[6]

The popliteus muscle has several surrounding attachments and ligaments; the most important ones include ligamentous connections to the lateral meniscus and fibular head that form during the cavitation that ultimately forms the residing bursa and form obliquely consistent with the musculotendinous structures. Although there is no direct ligamentous attachment from the posterolateral femur to the tibia, an indirect relationship exists between the popliteal tendon and the fibular head, known as the popliteofibular ligament.[7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial supply to the popliteus is provided by the medial inferior genicular branch of the popliteal artery and muscular branch of the posterior tibial artery.[8] Lymphatic drainage extends to the popliteal nodes and subsequently drains to the deep inguinal nodes of the thigh. Mapping and determining lymphatic flow is important when considering infectious or metastatic processes.[9]

Nerves

The tibial nerve innervates the popliteus from spinal nerve roots L5 through S1. Previous studies revealed approximately 2 to 3 parallel tibial nerve branches. The entry point of the nerve is the lateral distal margin of the muscle found inferior to the fibular head. After entry, the nerve splits into anterior, medial, and lateral distributions throughout the muscle.[10]

Muscles

There are four compartments of the leg, of which the deep posterior compartment is where the popliteus resides. Other muscles that are also in the deep posterior compartment accompanying the popliteus are the following:

- Flexor hallucis longus: Originates at the distal portion of the fibula and inferior interosseous membrane and inserts at the base of the distal phalanx of the great toe. It is innervated by the tibial nerve (S1, S2) and functions to support the medial longitudinal arch of the foot. Contraction also flexes the great toe and serves as a secondary plantar flexor.

- Flexor digitorum longus: This muscle originates at the posteromedial aspect of the tibia and broad tendon of the fibula. Insertion is seen at the distal phalanges of digits 2 to 5 and also receives innervation from the tibial nerve (S1, S2). It supports longitudinal arches, enables plantarflexion of the ankle and flexion of toes 2 through 4

- Tibialis posterior: Originates from the interosseous membrane, posterior tibial surface inferior to the soleal line, and posterior fibular surface. The tibialis posterior inserts at the tuberosity of navicular, cuneiform, cuboid, and sustentaculum tali of the calcaneus in addition to the bases of metatarsals 2 to 4. It is innervated by the tibial nerve (L4 to L5). This muscle is a major plantar flexor and inverter of the ankle.

Physiologic Variants

Occasionally, a small sesamoid bone called a cyamella can be seen embedded in the popliteal tendon. Sesamoid bones are accessory bones typically found in muscles or tendons that assist in physiologic function. The cyamella is located in the tendon inferior to the joint line or at the musculotendinous junction, which is superior to the joint line. Articulation can be seen with the lateral condyle of the tibia and is naturally close to the fibular head. This variant does not usually become physically impairing, but it can cause pain mimicking a posterolateral meniscal tear.[11]

The popliteus minor and peroneal tibialis muscles are uncommonly seen relative to the popliteus. The popliteus minor, if present, can be found medial to the plantaris and inserts onto the posterior ligament of the knee. The peroneal tibialis is also seen in a limited portion of the general population. When present, it can be found lying below the popliteus, medial to the fibular head, and extending to the superior portion of the oblique line of the tibia. Both structures have received very limited discussion in the current literature.

Surgical Considerations

Total Knee Replacement

Although the most recent reports still cite that up to 1 in 5 patients remain dissatisfied following TKA, the risks of patient-reported dissatisfaction can be mitigated by selectively operating on patients that have had other potentially relevant clinical pathologies like hip and/or back conditions ruled out as confounding pain generators. Success following TKA results in significant improvements in patient-reported pain and functional outcome scores in the short- and long-term postoperative periods.[12] One reason for unexplained persistent knee pain following a total knee replacement is secondary to popliteal impingement on the femoral component during total knee range of motion.

Mechanical symptoms can develop following this major operation due to interaction with femoral components of the prosthesis. Ultrasound-guided injections can confirm the diagnosis and may be used therapeutically if the patient finds consistent relief; however, there is a higher infection risk with injecting around a prosthetic knee.[13] Ultimately, the patient may benefit from popliteal tendon release due to extensive scar tissue development of the tendon following a total knee replacement.[14]

Another consideration that may also be taken to avoid popliteal tendon dysfunction is the actual size of the prosthesis. The variation in the size of femoral and tibial components, even if fitted appropriately, can result in popliteal tendon impingement. Studies have shown that normalized or oversized tibial components can lead to abnormal physiologic function of the popliteus through the arc of motion of the lower extremity. Undersized tibial components showed no change in pre-surgical physiological motion.[15]

Approaches to the Knee

Several approaches to the posterolateral corner of the knee have been described in the literature concerning popliteal tendon repair. Historically, the more common approach has been an open repair, but arthroscopic techniques have been developed in recent years. The popliteal tendon insertion is intracapsular, so a capsulotomy must be performed when using an open approach. The surgeon must consider the possible complications due to exposure, such as wound drainage, intraarticular sinus formation, infection, and stiffness. Arthroscopy certainly comes with risk, as does any operation; however, this approach may limit the mentioned complications.[16]

Clinical Significance

Posterolateral Corner Knee Injuries

The popliteus is most often injured as part of an associated posterolateral corner (PLC) knee injury. PLC injuries occur secondary to:

- Direct blows to the anteromedial knee

- Varus blows to the flexed knee

- Varus/hyperextension (contact or non-contact injuries)

- Knee dislocations

In any setting of these injuries mentioned above, an urgent evaluation of the patient's neurovascular status of the limb is performed. In the setting of knee dislocations, the vascular status of the limb is assessed, followed by a closed reduction of the knee joint. The vascular status is then reassessed, typically utilizing ankle-brachial index (ABI) measurements. Patients should be admitted for serial observations, and in some situations, either an external fixator must be placed by the orthopedic surgeon or a vascular repair is performed by the trauma/vascular surgeon on call. Concerning the latter two modalities, the external fixator is placed prior to the vascular repair to optimize the knee/limb stability prior to performing the potentially limb-saving vascular repair.

PLC knee injuries are clinically examined utilizing the following exam maneuvers:

- Varus stress at 0 degrees of knee extension: positive laxity indicates injury to the LCL and one of the cruciate ligaments (ACL or PCL)

- Varus stress at 30 degrees of knee extension: positive laxity at 30 degrees indicates injury only to the LCL (much more rare)

- Dial test: External rotation is compared between the normal and injured lower extremity. External rotation asymmetry (> 10 degrees) of the affected side compared to the normal side at 30 degrees only is an indication of PLC injury; If the external rotation asymmetry persists at 90 degrees as well, this would suggest a combined injury to the PLC and PCL.

Isolated Popliteus Injuries

The Garrick test can assist in assessing the popliteus muscle as the etiology of the lateral knee pain. The Garrick test consists of the patient lying supine with hips and knees flexed to 90 degrees with subsequent resisted internal rotation and passive external rotation of the knee. If either elicits pain, the test is considered positive and may suggest popliteal etiology, although accuracy has not been evaluated. Symptoms can be reproduced by downhill running with exaggerated stride length. Ultrasound imaging and MRI may also help confirm the diagnosis.[17]

Popliteus tendinopathy is a condition presenting as posterolateral knee pain that can be difficult to single out due to other more common knee pain etiologies in the vicinity. The popliteus inhibits excessive tibial rotation and prevents significant anterior translation of the knee. This mechanism can be pathologically overcome secondary to excessive sprinting or running downhill. Clinicians should advise patients to avoid terrain that has exacerbated their symptoms. They may re-introduce physical activity by running on flat surfaces such as a treadmill, but those who have a more difficult recovery may benefit from a course of physical therapy or a home exercise program. NSAID medication or cryotherapy may be added to the patient's regimen, which could be beneficial during the recovery phase. Lunge exercises also have been shown to improve stabilization of the knee, and the patient may increase weight resistance as pain allows. It is important to gradually increase the workload on the lower extremity to avoid re-injury or exacerbation that may lead to a chronic problem.[18]

Most of these injuries heal without further issue or complication. Recovery time may take anywhere from 3 to 16 weeks, and the patient can resume full physical activity without restriction after completing a functional assessment. Professional, functional assessment has been found to be more reliable in terms of return to restrictionless activity than a set time.