Continuing Education Activity

Plantar fasciitis, a prevalent and often vexing condition, arises from the degenerative irritation of the plantar fascia origin at the medial calcaneal tuberosity of the heel and its surrounding perifascial structures. The plantar fascia comprises 3 segments originating from the calcaneus and plays a pivotal role in maintaining the normal biomechanics of the foot, providing essential arch support, and serving as a shock absorber. An absence of inflammatory cells characterizes this condition despite its name. In the United States, millions of individuals suffer from heel pain each year, with plantar fasciitis being a primary culprit. While multifactorial in its origins, overuse stress is often the leading cause, presenting with sharp localized pain at the heel and, occasionally, a heel spur. Non-surgical approaches are the primary mode of management, yet recurrent pain can be frustrating for both patients and healthcare providers.

This continuing education activity provides healthcare professionals with a comprehensive review of the evaluation and treatment of plantar fasciitis. To enhance diagnosis and treatment, participants gain a deeper understanding of this condition, including the etiology and absence of inflammatory involvement. The course explores the multifaceted role of the medical team in evaluating and managing plantar fasciitis. For primary care physicians, orthopedic specialists, or physical therapists, this course provides the knowledge and tools to assist patients experiencing plantar fasciitis, ultimately improving their overall quality of life.

Objectives:

Evaluate the underlying pathophysiologic cause of plantar fasciitis.

Identify the normal biomechanics of the foot and the role of the plantar fascia.

Compare the management options available for treating plantar fasciitis.

Apply interprofessional team strategies that can be employed to provide the best outcomes in the evaluation and treatment of plantar fasciitis.

Introduction

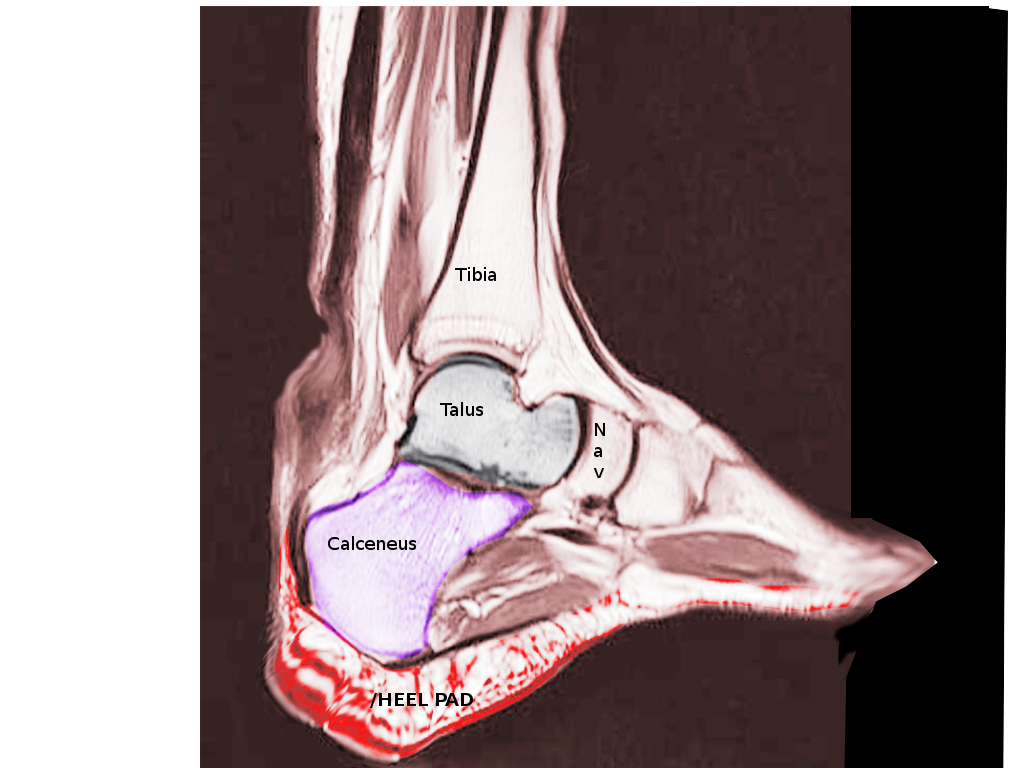

Plantar fasciitis occurs due to degenerative irritation at the origin of the plantar fascia, located at the medial calcaneal tuberosity of the heel and the surrounding perifascial structures. The plantar fascia plays an essential role in the normal biomechanics of the foot and comprises three segments arising from the calcaneus. The fascia is essential in supporting the arch and providing shock absorption. Despite featuring the -itis suffix in the diagnosis, this condition stands out for its absence of inflammatory cells.

Plantar fasciitis is prevalent in the United States, with millions experiencing heel pain annually. The cause of plantar fasciitis is multifactorial, but most cases result from overuse stress. The classic presentation is of sharp localized pain at the heel.[1] Occasionally, a heel spur may be found (see Images. Lateral Radiograph, Heel Spur and Large Heel Spur and Plantar Calcaneal Spur). Plantar fasciitis is not easy to treat, and patient dissatisfaction is common with most treatments. Nonsurgical management handles most cases, but the recurrence of pain proves frustrating.

Etiology

Plantar fasciitis is often an overuse injury primarily due to a repetitive strain causing micro-tears of the plantar fascia. Still, this condition can occur due to trauma or other multifactorial causes. Some predisposing factors are pes planus, pes cavus, limited ankle dorsiflexion, prolonged standing or jumping, and excessive pronation or supination.[2][3] Pes planus can cause increased strain at the origin of the plantar fascia. Pes cavus can cause excessive strain on the heel because the foot does not effectively evert or absorb shock. Tightness in the gastrocnemius, soleus, and other muscles situated in the posterior leg is common for patients with this condition. Tight muscles can alter the normal biomechanics of ambulation.

Approximately 50% of patients with this condition will also have heel spurs, but the spurs are not the cause. Plantar fasciitis is often associated with runners and older adults, but other risk factors include obesity, heel pad atrophy, aging, occupations requiring prolonged standing, and weight-bearing. Plantar fasciitis is associated with various seronegative spondyloarthropathies, but there are no known systemic factors in approximately 85% of cases.

Epidemiology

Plantar fasciitis is the most common cause of heel pain presenting in the outpatient setting. The exact incidence and prevalence of plantar fasciitis by age are unknown, but estimates show that approximately 1 million patient visits annually are due to plantar fasciitis. This condition accounts for about 10% of runner-related injuries and 11% to 15% of all foot symptoms requiring professional medical care. Plantar fasciitis occurs in about 10% of the general population, with 83% of these patients being active working adults between 25 and 65 years. The peak incidence is among the general population of 40 to 60 years.[4] Plantar fasciitis may present bilaterally in a third of the cases. In addition, a higher prevalence of plantar fasciitis was observed in women compared to men, in those aged 45 to 64 versus those aged 18 to 44, and in those with a body mass index >25 kg/m2.[5] Some literature shows that runners' prevalence rates are as high as 22%.

Pathophysiology

This condition is primarily a degenerative process. Aside from degenerative changes, histological findings include granulation tissue, micro-tears, collagen disarray, and a notable lack of traditional inflammation. Ultrasound evaluation often reveals calcifications, intra-substance tears, and thickening and heterogeneity of the plantar fascia. These changes, often seen on ultrasound, suggest a noninflammatory condition and dysfunctional vasculature. One study included magnetic resonance imaging showing chronic fasciitis in 8 cases and an old rupture of the plantar fascia in 30 patients.[6] Microtears occur due to the repetitive stress of standing upright and bearing weight, initiating the condition. The constant stretching of the plantar fascia results in chronic degeneration of the fascia, eventually leading to pain during sleep or at rest.

History and Physical

Patients often present with a history of progressive pain at the inferior and medial heel, but pain can radiate proximally in more severe cases. They will often describe the pain as sharp and worse with the first few steps out of bed in the morning. Long periods of standing, or in severe cases, sitting for prolonged periods will also exacerbate symptoms. Pain often decreases with ambulation or the beginning of an athletic activity but then increases throughout the day as activity increases. Pain can usually be reproduced by palpating the plantar medial calcaneal tubercle at the site of the plantar fascial insertion on the heel bone. Passive dorsiflexion of the foot and toes can reproduce the pain. The windlass or Jack test specifically involves actively reproducing pain through passive dorsiflexion of the first metatarsophalangeal joint, and it is positive if the pain is elicited.[7] Secondary findings may include a tight Achilles heel cord, pes planus, or pes cavus (see Images. Dorsal Radiograph, Achilles Tendon and Achilles Tendon Anatomy).

Assessing a patient's gait to evaluate for biomechanical factors or predisposing factors mentioned previously may also be beneficial. When diagnosing plantar fasciitis, one should consider fat pad contusion or atrophy, stress fractures, and nerve entrapments such as tarsal tunnel syndrome in the differential.

Evaluation

Plantar fasciitis is a clinical diagnosis, and imaging is unnecessary. A provider may consider obtaining x-rays or ultrasound evaluation if history or physical exam indicates other injuries or conditions or the patient fails to improve after a reasonable amount of time. X-rays and ultrasound evaluation may show calcifications in the soft tissues or heel spurs on the inferior aspect of the heel.[8] Additionally, ultrasound may show thickening and swelling of the plantar fascia, a typical feature.[9] If the patient is not responding to conservative therapy after more extended periods, then the provider may consider ordering magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate for tears, stress fractures, or osteochondral defects.

The presence of plantar fasciitis can be identified on magnetic resonance imaging by the thickening of the plantar fascia and increased signal on delayed and short tau inversion recovery images.[10] Technetium scintigraphy is another diagnostic method that can successfully locate the inflammatory focus and exclude the presence of a stress fracture.[11][12]

Treatment / Management

Guided by the pain level, administer relative rest from the offending activity as the first-line treatment. Ice after activity, as well as oral or topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, can help alleviate pain. Results from studies show that deep friction massage of the arch and insertion, along with the prescription of shoe inserts or orthotics and night splints, can offer benefits.[13] Prefabricated silicone heel inserts, along with stretching exercises, can also be of help.[14] Providers should educate patients on proper stretching and rehab of the plantar fascia, Achilles tendon, gastrocnemius, and soleus.

If the pain does not respond to conservative measures, consider more advanced or invasive techniques such as extracorporeal shock-wave therapy, botulinum toxin A, or various injections, including autologous platelet-rich plasma, dex prolotherapy, or steroids.[15][16][17] The more advanced and invasive techniques should be combined with conservative therapies. Surgery should be the last option if this process has become chronic and other less invasive therapies have failed. A minimum of 6 weeks is required for the therapy, regardless of the selected treatment. Simultaneously, consider recommending stretching, icing, and strapping of the heel. Urge the patient to modify work-related activities. A night splint may help patients with recalcitrant pain.[18]

Reserve surgery as a last resort, typically for patients who do not respond to nonoperative therapy for at least 6 to 12 months.[19] Consider performing fasciotomy through an open or endoscopic approach. However, the surgical release does not guarantee a successful outcome. Complications of surgery include nerve injury, plantar fascia rupture, and flattening of the longitudinal arch. Whether stretching or controlling running intensity can prevent plantar fasciitis remains unclear. Shock-absorbing footwear may help. Study results found that a contoured foot orthosis reduced injuries compared to a flat insole. More research is needed to determine its effectiveness.

Differential Diagnosis

Possible differential diagnoses include the following:

- Calcaneus injury

- Infection

- Sickle cell bony pain

- Bone contusion

- Neuropathic pain

- Tendinitis

- Osteoporosis

- Malignancy

Considering and evaluating these conditions is crucial for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Prognosis

About 75% of cases resolve spontaneously within 12 months. About 5% need surgery, but the results are not consistently positive. Even with treatment, the resolution of symptoms can take weeks or months.[20] The morbidity from plantar fasciitis is significant, as the condition requires time off from physically demanding work and sports. Some individuals require an ambulatory device to avoid weight-bearing.

Complications

Complications of plantar fasciitis include the following:

- Rupture of the tendon, primarily if corticosteroid injections are employed

- Fat pad necrosis

- Flattening of the arch

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be encouraged to stretch their feet regularly, especially before and after exercise. In addition, they should be advised about proper footwear, as wearing shoes that provide adequate support and cushioning can help reduce the risk of developing plantar fasciitis. Moreover, patients should be encouraged to gradually increase their activity level to avoid overuse injuries and to maintain healthy weight management.

Pearls and Other Issues

Following the diagnosis of plantar fasciitis, a comprehensive and patient-centric approach is essential for effective management. This condition, though often self-limiting with symptoms resolving within 12 months, requires diligent follow-up and consideration of individualized treatment strategies. Persistent symptoms, especially in chronic scenarios, require a more nuanced approach. This intervention involves exploring advanced therapies and assessing gait and biomechanical factors for potential correction through gait retraining. While corticosteroid injections offer short-term relief, their long-term efficacy is limited. Additionally, there exists a landscape of conflicting evidence regarding the effectiveness of advanced treatments such as platelet-rich plasma, dex prolotherapy, and extra-corporeal shockwave therapy.[21] This information underscores the importance of tailored care, emphasizing follow-up, patient education, and a judicious selection of interventions based on the evolving needs of individuals with plantar fasciitis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional approach to plantar fasciitis is preferable, as no single treatment works for everyone. Plantar fasciitis affects many people, usually young people and athletes. The condition can be disabling if not appropriately managed. The nurse, pharmacist, physical therapist, and rehabilitation specialist are vital in managing symptoms and patient education. Patients should be informed that improvement in symptoms may take weeks or months. In addition, the patient may have to enroll in a physical therapy program or wear a night splint. Patients should be instructed on how to stretch the plantar fascia through home exercises.

Additionally, obtaining shoes with appropriate arch support may require a podiatry consult. Educate patients to avoid long periods of standing. Losing weight and stretching before starting an exercise program is essential. Advise individuals with acute symptoms to avoid walking barefoot and limit repetitive exercises that traumatize the heel. If this treatment plan fails, referral to an orthopedic surgeon is the last resort.

Plantar fasciitis may be a benign disorder, but if not adequately managed, it can be disabling and associated with moderate to severe pain. About 70% to 80% of patients with plantar fasciitis see symptom reduction in 9 to 12 months. However, at least 5% to 10% require surgical plantar fascia release.[22] Plantar fasciitis in athletes is associated with high morbidity, and even when managed appropriately, recurrences are not uncommon. The morbidity of plantar fasciitis is due to pain in the foot, difficulty with ambulation, limitation in exercise, and inability to bear weight. Sometimes, uneven ambulation can also lead to an injury of the knee and hip joints. Among people who have to stand for long hours, plantar fasciitis is one of the most common causes of worker's compensation claims.