Definition/Introduction

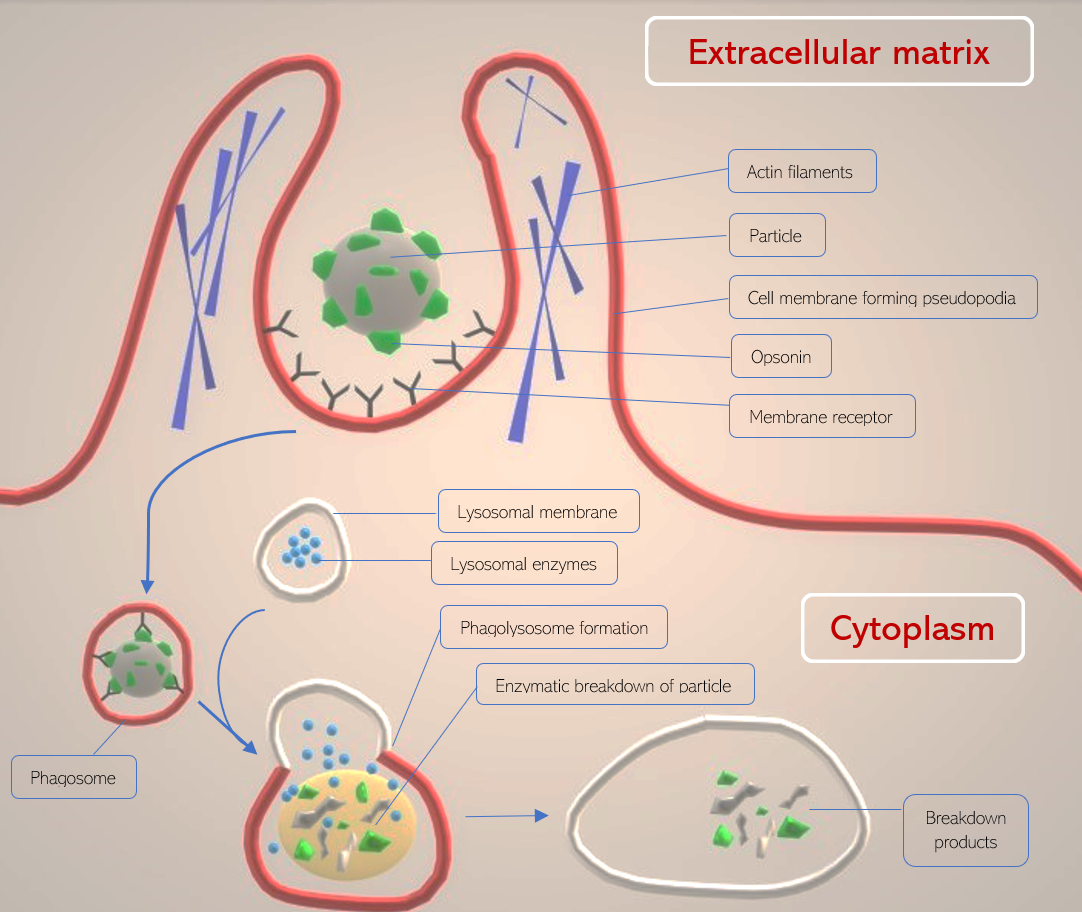

In phagocytosis, the plasma membrane of a cell is directed by cytoskeletal filaments to form pseudopodia (fake arms) that act to engulf a particle and bring it into the cell from the extracellular matrix. Once engulfed, the particle remains compartmentalized in an intracellular vesicle known as a phagosome and eventually undergoes lysosomal degradation in the phagocytic pathway. Phagocytosis is primarily a eukaryotic process.[1]

Since phagocytosis is a cell-mediated process involving the transport of a substance from the extracellular matrix into the cell, it is considered a form of endocytosis. Specifically, phagocytosis is a form of endocytosis that only involves the transport of larger particles (greater than 0.5 micrometers), such as bacteria or cellular debris. Phagocytosis is also described as a destructive endocytosis due to the fate of particles being endocytosed.[2]

The discovery of phagocytosis was made by Dr. Ilya Mechnikov, a pioneering scientist in the fields of immunology and zoology. The term “phagocytosis” derives from the Greek words “phagein” and “kytos,” which roughly translates to the phrase “to devour cell” – fittingly describing what this process appears to resemble under the microscope.[3]

Issues of Concern

A large spectrum of particles can be sequestered through phagocytosis. Thus, the process is heavily utilized by the human host immune systems – whether host macrophages are clearing dead cell debris or capturing bacterial pathogens with the help of opsonins. Many cell types are capable of performing phagocytic endocytosis in the body; however, certain cells are specialized to primarily perform phagocytosis. For example, dendritic cells capture bacteria, digest, and subsequently present bacterial component proteins to helper T-cells. The initiation of helper T-cell division by dendritic cells is just one of many instances phagocytosis linking the innate and adaptive immune responses.[4]

Receptor-lead Activation

To stimulate phagocytosis in the cell, several triggers that involve the activation of receptors may occur, depending on the type of cell:

- In the case of Fc-gamma receptors (such as Fc-gamma III), the Fc portion of plasma membrane-bound IgG antibodies detect particles coated with IgG (acting as an opsonin). This activity stimulates an intracellular domain known as ITAM, resulting in signal transduction and the formation of pseudopodia with the help of actin filaments and myosin of the cytoskeleton. In neutrophils, the activation of the ITAM receptor also induces reactive oxygen species formation (oxidative burst).[5]

- In the case of mannose receptors (mannose is a monosaccharide), a bacterial glycan attached to a protein (such as mannose or N-acetyl glucosamine) is detected by the mannose receptor containing multiple fibronectin-2 domains, triggering direct phagocytosis (thus behaving as a pattern recognition receptor or PRR). The mannose receptor does not induce the formation of pseudopodia, and thus mechanistically is different from Fc-gamma phagocytosis[6].

- Complement receptors behave similarly to Fc-gamma receptors in that they detect an opsonin attached to the pathogenic particle. In this case, the opsonins are complement molecules C3b and C4b. Like the mannose receptor, these receptors do not stimulate pseudopodia formation.[7]

- In the case of opsonin-dependent receptors (such as Fc-gamma and complement receptors), secondary signals must become activated to complete the initiation of phagocytosis. Specifically, the Nf-kB complex (Nf-kBc) must activate to initiate specific gene transcription. Nf-kBc activation becomes stimulated by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). The induction of PRRs is by receptor ligands known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Phagocytic cells also contain other receptors, such as scavenger receptors and LPS receptors, that stimulate phagocytosis without the use of an opsonin. Such receptors bind to ligands such as PAMPs and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) to stimulate phagocytosis.[8]

Receptor-led Formation of the Phagosome

Once a receptor (such as Fc-gamma III) and its secondary stimulator (such as mannose receptor) activate phagocytosis, the cytoskeletal filaments actin and myosin perform a contractile mechanism to envelope the particle by surrounding it in cell membrane projections (pseudopodia). The projections circle around the particle, and a vesicle forms from the fusion of the cell membrane. The particle remains attached to the cell membrane receptors as it is internalized into the cell within the phagosome. Once in the cytoplasm, the phagosome is considered a cellular organelle.[9]

As the phagosome traverses in the direction of the phagocyte’s centrosome, it fuses with a lysosome containing degradative enzymes such as proteases and iron-sequestering molecules such as lactoferrin. This fused organelle is termed the phagolysosome and gradually acidifies to activate proteolytic and degradative enzymes.[9]

During the phagolysosomal degradation of the particle, granules containing antimicrobial peptides such as defensins surround and degrade the particle. Simultaneously, other elements of the granules, including lysozymes, DNA-ases, elastases, and lipases, further degrade the components of the particle. In some phagocytic cells, this process is accompanied by generating reactive oxygen species by NADPH oxidase and other enzymes such as myeloperoxidase. The NADPH-oxidase reaction is NADPH and oxygen-dependent (NADPH acts as a proton donor). The production of hypochlorous acid is catalyzed by myeloperoxidase in the phagolysosome.[2]

Professional Phagocytes

Professional phagocytic cells are a class of cells that mature specifically to perform phagocytosis to assist in functions such as bone resorption and antigen presentation. This class includes dendritic cells, eosinophils, monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils and osteoclasts, and more. The variety of tasks these cells accomplish is enabled by their ability to phagocytose particles in the extracellular matrix. Monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils are particularly strong phagocytes, playing a more significant role in the innate immune response through their microbicidal and antigen-presenting capabilities.[10]

During neutrophilic phagocytosis, a pathogenic particle (such as a bacterium) is detected by Fc-Gamma receptors on the neutrophil’s cell membrane (complement receptors may also perform this function), triggering a cytoskeletal rearrangement, phagocytosing the foreign particle, and sequestering it in the phagosome. Granzyme proteases in the neutrophil’s cytoplasm (such as collagenase and myeloperoxidase) coupled with oxidative bursts (producing reactive oxygen species) result in the destruction of the particle within the phagosome.[2]

Macrophages (which are simply monocytes that have migrated into tissue and differentiated) utilize multiple receptors to detect pathogenic particles. Receptors include but are not limited to the scavenger receptors (similar to SCARB1), mannose receptors, and Fc-gamma receptors - all of which are present on the cell membrane.[10]

Clinical Significance

Although phagocytosis is a potent defense mechanism, certain common pathogenic species can evade the process, including E. coli and S. aureus. For example, S. aureus secretes a protein termed extracellular fibrinogen-binding protein (Efb), which binds fibrinogen in the blood, generating a shield-like capsule around the bacterium to evade phagocytosis. The Efb protein also binds complement protein C3, resulting in impaired opsonin recognition and reduced phagocytosis.[11]

Impaired phagocytosis can also lead to the development of autoimmune disorders. Post-apoptotic cells contain uniquely identifiable surface markers, such as phosphatidylserine. Like PAMPs, such molecules can be recognized by specialized receptors on phagocytic cells, triggering phagocytosis and subsequent clearance of dead-cell debris. In efferocytosis, macrophages surround apoptotic cells and phagocytose them to clear the tissue region containing them. However, if phagocytosis is non-functional in macrophages, post-apoptotic molecules remain trapped in the tissue and may trigger the development of autoantibodies. Moreover, phagocytosis itself could be detrimental to cellular components. For example, macrophages phagocytose neuronal myelin in peripheral demyelinating disorders.[12]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

The management of resistant staphylococcal infections (such as MRSA) requires a dedicated interprofessional team, relying on the multidisciplinary skill sets of individuals in pharmacology, medicine, nursing, and infectious disease. The rate of iatrogenic disease spread must be contained through team efforts of proper handwashing and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE). Identifying appropriate treatment modalities that account for resistance mechanisms (such as Efb protein) must be employed by physicians and pharmacologists, while patient monitoring under nursing team members is crucial to the patient and family members’ safety. Acute hospital care knowledge regarding MRSA management, infection source, and geographic variability of resistant strains is crucial to treatment outcomes.[13] [Level 1]