Continuing Education Activity

The anorectal abscess can vary on the spectrum of complexity based on the location and involvement of surrounding tissue. A thorough knowledge of the anatomical structures and their relationship to each other is important for both accurate diagnoses of the disease and to provide appropriate treatment to avoid the complications of multiple procedures and increased costs associated with delayed diagnosis. This activity reviews the pathophysiology of a perirectal abscess and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Describe the etiology of anorectal abscesses.

- Contrast the types of anorectal abscesses that can be drained at the bedside with the types that require consideration of intra-operative draining.

- Explain the decision process for prescribing antibiotics to patients with anorectal abscesses.

- Identify ways that interprofessional team members can collaborate and improve care coordination to reduce anorectal abscess recurrence rate of enhance patient outcomes.

Introduction

The anorectal abscess can vary on the spectrum of complexity based on the location and involvement of surrounding tissue. A thorough understanding of the anatomical structures and their relationship to each other is important for both accurate diagnoses of the disease and to provide appropriate treatment to avoid the complications of multiple procedures and increased costs associated with delayed diagnosis.[1][2]

Etiology

Anorectal abscesses are typically caused by inflammation of the subcutaneous tissue usually from an obstructed crypt gland. The normal anatomy of the anus includes the presence of these glands at the dentate line. Debris overlying these glands are often the infiltrative mechanism by which the bacteria gain access to the underlying tissue and produce infection. As such, infective organisms that can cause this include Escherichia Coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Proteus, Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus, Porphyromonas, Fusobacteria, and Bacteroides. Risk factors that that may predispose patients to abscesses include trauma, tobacco abuse, liquid stool entering the duct, and dilated ducts which lead to poor emptying.[3][4]

About 10% of cases are associated with HIV, Crohn disease, trauma, tuberculosis, STDs, radiation, foreign bodies, and malignancy.

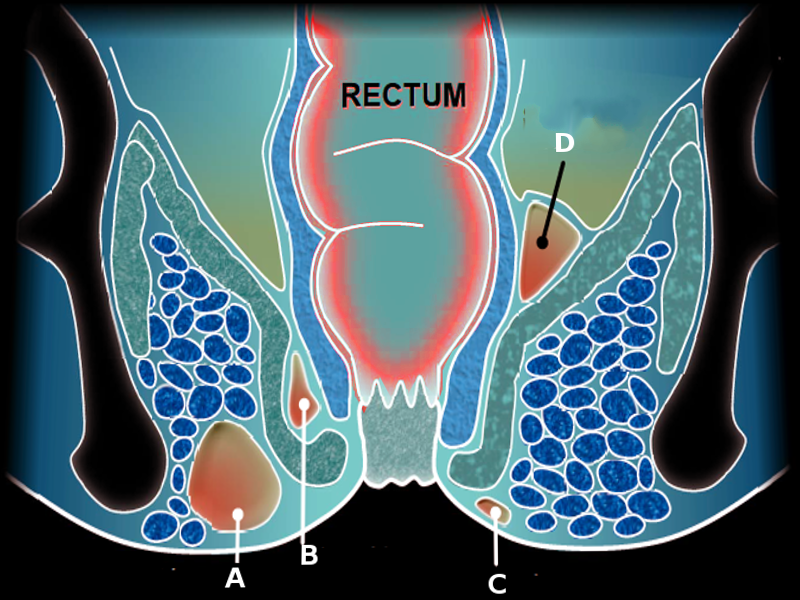

The location of anorectal abscess is as follows:

- Perianal- most common (60%)

- Ischiorectal (20%)

- Supralevator and intersphincteric (5%)

- Submucosal (less than 1%)

Epidemiology

The incidence is 1:10,000, resulting in approximately 68,000 to 96,000 cases in the United States per year with a male prevalence of 3:1 during the third and fourth decades of life. The condition is seen more in the summer and spring months. Although often a concern of the patient, data does not support that there is an increased risk from hygiene, anal-receptive intercourse, diabetes, obesity, race, or altered bowel habits. The disorder appears to be more common in men than women.[5][6][7]

Pathophysiology

Although often thought of as the same, perianal abscess and perirectal abscesses differ in both complexity and care options. Except for perianal abscess which can be simply incised and drained as definitive care, all others usually require intravenous antibiotics, surgical evaluation, and drainage. A majority of abscesses are diagnosed clinically based on skin findings and palpitation of the affected area alone, but some require advanced imaging to determine the extent of infiltration. A perirectal abscess can be further divided into a category based on anatomical location: ischiorectal abscess, intersphincteric abscess, and supralevator abscess. Given the variability in location and severity of the abscess, it is important to consider the presence of fistulas or tracts which may contribute to the spread of the infection. Perianal abscesses are the most common type, followed by ischiorectal, and intersphincteric abscesses.[8]

Alternatively, the Park’s classification system which groups the fistulas into 4 types based on the course of the fistula and the relationship to the anal sphincters.

- Intersphincteric (70%): Between the internal and external sphincters

- Trans-sphincteric (25%): Extends thru the external sphincter into the ischiorectal fossa

- Suprasphincteric (5%): Passes from the rectum to the skin through the levator ani

- Extrasphincteric (1%): Extends from the intersphincteric plane through the puborectalis

History and Physical

Patients will often present to the emergency department with acute pain in the perianal or perirectal region. Other presenting symptoms include a dull or aching pain with defecation, movement, sitting, or coughing. Supralevator abscesses may be described as lower back pain or a dull ache in the pelvic region. Also, fever, malaise, rectal drainage, redness of surrounding skin, and possible urinary retention may be included in the patient history.

Most physical exams are done in the prone or left lateral decubitus position, revealing erythema, induration, fluctuance, tenderness, and spontaneous drainage. Pertinent physical exam findings, often performed in the Sim position, include erythema of the surrounding skin, superficial or deep mass with tenderness to palpation, tenderness on palpation of the rectum and deep structures, or discharge. A digital rectal exam may aid in the diagnosis, but variability exists among physicians' ability to identify the abscess on the exam accurately. Constipation or tenesmus may be present in patients that have significant pain with a bowel movement.

In most patients, a complete digital rectal exam is not possible without anesthesia. In order to visualize the fistula opening, examination under anesthesia is usually necessary.

Evaluation

Laboratory abnormalities may include elevated white blood cell count, increased neutrophils, the presence of bands, and elevated lactate levels. Imaging modalities such as endoanal ultrasound, transperineal sonography, computed tomography (CT), and MRI are useful to confirm the diagnosis. CT should be obtained in patients with significant comorbidities, complex suppurative anorectal conditions, and when surgical consultation may not be immediately available. Optimal imaging may require utilizing triple contrast in certain conditions and using 2.5 mm slices. Endoanal ultrasound imaging is best captured by using a 2-dimensional or 3-dimensional probe with a frequency of 5 to 16 MHz.[9][10]

Treatment / Management

As with all abscess, once identified, the mainstay of treatment is incision and drainage given the significant concern of extension into nearby tissue. Simple, superficial perianal abscess and some ischiorectal abscesses can be drained at the bedside. A horseshoe abscess is a large abscess in the deep postanal space which extends bilaterally to the ischiorectal fossae. This must be treated in the operating room by a specialist. For superficial perianal abscesses, giving the appropriate amount of anesthetic with epinephrine should be sufficient to adequately incise and drain the abscess. Typically, the incision is cruciate or elliptical and made as close as possible to the anal verge to minimize the potential long fistula formation. Given that a large number of abscesses are associated with a fistula, concomitant fistulotomy or seton placement may be performed with varying results. However, compared to an incision and drainage, a fistulotomy is associated with a significantly lower rate of recurrence. Packing of the wound is controversial, but Perera et al. did not find significant evidence to support an advantage over packing the wound compared to incision and drainage without packing.[11][12][13]

Surgeons should perform an examination under anesthesia to evaluate patients with recurrent or bilateral abscesses for intraoperative drainage, including cases where internal draining may be necessary. A larger abscess may require placement of a drain for up to 3 weeks. Catheters are also recommended for patients with severe systemic illness, underlying comorbidities including diabetes and morbid obesity. The catheters can be placed after a small stab incision is made through the skin using a mushroom tip catheter 10 to 14 Fr which is then secured to the skin with a suture. Surgeons generally follow up at 2 to 3 weeks for incision and drainage patients, and 7 to 10 days for patients with mushroom tip catheters. They are usually followed until completely healed. A high fiber diet is recommended.

Some surgeons do advocate a diverting colostomy in severe cases but the infection may persist despite the colostomy. The key is to provide adequate drainage to control the infection.

The management of fistula is not easy and there are several methods to manage them including:

- Seton treatment

- Fistulotomy

- Fistulectomy

- Glue therapy

- Marsupialization

- Anal flap

Antibiotics are recommended when there is associated cellulitis of the surrounding skin, patients that fail to improve after drainage and immunocompromised patients. Currently, no data exist to suggest that antibiotics will reduce fistula formation. Antibiotics should include coverage for the organisms listed above. We recommend obtaining wound cultures if antibiotics are prescribed, especially those who already have completed a prior course, or known resistance in the past. We recommend treating with amoxicillin-clavulanate or ciprofloxacin plus metronidazole for 10 days.

Admission is recommended for patients who are frail, have a fever, hypotensive or immunosuppressed.

Patients should be made aware that healing is not immediate and pain may be moderate to severe after surgery.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes anal fissure, anal fistula, thrombosed hemorrhoid, pilonidal cyst, buttocks abscess, or cellulitis of the skin, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, malignancy, proctitis, HIV/ AIDS, other sexually transmitted diseases, Bartholin’s abscess, and hidradenitis suppurativa.

Prognosis

Perirectal abscess has very high morbidity. Recurrence and chronic pain may occur in more than 30% of patients. The development of a chronic fistula is very common if the disorder is treated only by incision and drainage. Other complications include urethral irritation, urinary retention, and constipation.

Even with fistulotomy or the use of a Seton, recurrence rates of 1-3% have been reported.

Risk factors for fistula development include young age and absence of diabetes. After surgery. The quality of life in patients with recurrent anorectal abscess is poor.

Complications

- Bacteremia/sepsis

- Fistula formation

- Fecal incontinence

- Urinary retention

- Constipation

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

After treatment, the patient needs pain control, laxatives to avoid constipation and instructions on sitz baths.

Outpatient antibiotics may be indicated depending on the culture and sensitivity of the organism.

Because of a high recurrence rate, all patients need to be followed up until there is complete healing, which may take anywhere from 3-8 weeks.

Consultations

Any anorectal abscess that is not easily visible/palpable should be evaluated by a surgeon.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Perirectal abscess affects many people in between the third and fourth decade of life. These abscesses are extremely difficult to treat and errors in management can lead to fistula formation. Many patients have repeated visits to the emergency room for urinary retention, pain, fecal incontinence, and chronic constipation- all of which lead to a rise in healthcare costs. Thus, these lesions are best managed by an interprofessional team that includes the following:

- The emergency department physician to manage the acute pain, urinary retention, and bacteremia

- The colorectal surgeon who performs the fistulotomy or Seton placement

- Nurse practitioner to follow the patient in the clinic to ensure complete healing which may take 4-8 weeks. Patients with Crohn disease, radiation injury, HIV, malignancy or trauma may require even longer follow up as healing is delayed. The nurse is also responsible for teaching the patient how to use a sitz bath to maintain perineal hygiene and obtain pain relief

- Dietitian to educate the patient on a high fiber diet to relieve constipation

- Infectious disease nurse to educate and monitor the patient on the maintenance of personal hygiene, safe sex practice and remain compliant with antibiotics.

Patients with Crohn disease often require life long monitoring as they have a high recurrence rate.

Outcomes

While the mortality from a perirectal abscess is low, the morbidity is very high. These lesions can cause significant anorectal pain, urinary retention, and fecal incontinence. In addition, the quality of life in patients with recurrence is poor. Most patients with recurrence require multiple hospital admissions for pain management, urinary retention, and constipation. Premature surgery or a simple incision and drainage by a clinician not familiar with this disease can lead to a chronic fistula which can take months or even years to heal. Thus, it is vital that patients with perirectal abscess be managed by an interprofessional team that communicates. Above all, if there is any doubt, a colorectal surgeon should be consulted before performing any type of invasive procedure.