Continuing Education Activity

The pericardium is the fibroelastic sac surrounding the heart. It is composed of two layers, visceral and parietal, that are separated by a potential space. Within this potential space, 15 to 50 milliliters of fluid exist to serve the purpose of lubrication. The term acute pericarditis refers to inflammation of this fibroelastic sac. The causes of pericarditis are wide-ranging and include infection, autoimmune processes, malignancy, and uremia. Uremic pericarditis typically occurs in patients with end-stage renal disease and patients with severe azotemia (elevated blood urea nitrogen, BUN), typically above 60 mg/dL. Clinical features of uremic pericarditis include chest pain, particularly in the recumbent position, a pericardial rub that is often audible, and in severe cases, cardiac tamponade may be present. This activity highlights the interprofessional team's role in caring for patients with uremic pericarditis.

Objectives:

- Review the pathophysiology of uremic pericarditis.

- Describe the presentation of uremic pericarditis.

- Summarize the treatment of uremic pericarditis.

- Outline interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance care and outcomes in patients with uremic pericarditis.

Introduction

The pericardium is the fibroelastic sac surrounding the heart. It is composed of two layers, visceral and parietal, that are separated by a "potential" space. Within this potential space, it is normal to have 15 to 50 mL of fluid to serve the purpose of lubrication. The term acute pericarditis refers to inflammation of this fibroelastic sac. The causes of pericarditis are wide-ranging, including infection, autoimmune processes, malignancy, and uremia.

Uremic pericarditis is an uncommon but significant complication of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Richard Bright described it for the first time in 1836. It was more common in the early days of dialysis; however, more recently, it has become an uncommon complication of ESRD potentially because of more efficient hemodialysis therapy. In the past, it was thought that a viral illness could cause uremic pericarditis.[1] Uremic pericarditis is fibrinous in nature with a rough fibrinous surface.[2] When there is fluid, it is generally exudative, with an abundance of proteins and mononuclear cells.

Uremic pericarditis typically occurs in patients with end-stage renal disease and patients with severe azotemia (elevated blood urea nitrogen, BUN), typically above 60 mg/dL. Clinical features of uremic pericarditis include chest pain, particularly in the recumbent position, a pericardial rub that is often audible, and in severe cases, cardiac tamponade may be present. Initial investigations for uremic pericarditis include an electrocardiogram, which typically shows diffuse ST and T-wave elevations. Treating this condition is often by lowering BUN through dialysis.[3][4]

Etiology

Patients with end-stage renal disease typically have a fluid and electrolyte balance defect leading to an accumulation of toxic metabolites such as nitrogenous wastes. Studies have shown that the combination of toxic metabolite accumulation, uremic toxins, fluid overload, and electrolyte derangement contributes to the pathogenesis of uremic pericarditis.[5] Some studies demonstrate that an increase in nitrogen waste products has a proinflammatory effect leading to pericarditis; other studies have concluded the changes in acid-base homeostasis, hypercalcemia, and hyperuricemia are all implicated in the development of uremic pericarditis.[3]

It is observed that uremic pericarditis occurs due to inadequate dialysis in stable ESRD patients or relatively inadequate dialysis in ESRD patients with higher catabolic activity because of multiple comorbidities. A rise in dialysis pericarditis has been observed in patients with vascular access issues causing missed or inadequate treatments.[6]

Epidemiology

The actual incidence of uremic pericarditis is difficult to ascertain due to the variability of symptoms and diagnostic criteria. Its prevalence used to range between 3% and 41%. Recently, it has reduced to approximately 5%-20% and less than 5% in the last decades due to improvements in hemodialysis therapy and a better understanding of complex metabolic changes around ESRD.[3][7][8]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of uremic pericarditis is primarily related to the accumulation of toxic metabolites and nitrogenous waste in the blood. Research shows that these toxic metabolites affect the pericardium resulting in the release of pro-inflammatory markers such as interleukin 1, interleukin 6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), leading to inflammation, fibrous deposition, and adhesions causing damage to the pericardium. In severe cases, effusions can also occur in conjunction with uremic pericarditis, which can be quantified further into serous versus hemorrhagic; the cause of these pericardial effusions is multifactorial and is partially related to platelet dysfunction in renal failure patients.[9][10]

The risk of cardiac abnormalities has been historically associated with renal impairment across several studies. The relationship between renal dysfunction and cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been defined as reciprocal or bidirectional.[11]

High albuminuria in chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with abnormalities in inflammation, fibrinolysis, and dyslipidemia.[11] Excess urinary albumin excretion aggravating endothelial permeability may have a role in the pathogenesis of pericarditis.[12] Patients on dialysis have high levels of free radicals, indicating uremia is a pro-oxidant state, but dialysis is not entirely effective in correcting oxidative stress.[13] The causal association between oxidative stress and CVD in ESRD patients has not been firmly established.[13]

History and Physical

A significant key finding in uremic pericarditis is the presence of chest pain in a patient with a history of chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease on dialysis. Most patients will present with pleuritic chest pain that improves when leaning forward. Acute non-uremic pericarditis usually presents with chest pain that is sudden in onset in the anterior chest, aggravates on inspiration and in the supine position, and could be accompanied by a pericardial friction rub. However, uremic pericarditis is gradual in onset, and aside from pericardial rub, there may not be any more findings. Other findings can include but are not limited to fever and shortness of breath. Many of these patients will present similarly to a myocardial infarction patient, so it is essential to rule out an ischemic event in the situation.[14][15][7]

Cardiac tamponade is seen in 20% of patients with dialysis-associated pericarditis, and dialysis-associated hypotension happens in 60% of cases in pre-tamponade or tamponade, in comparison to 6% in those without.[16]

Physical examination reveals a pericardial friction rub which is usually scratchy and squeaky and is best appreciated on the left sternal border with the patient leaning forward and holding their breath. It is almost always heard in uremic pericarditis cases, but sometimes it is transient in nature, heard at one point but not at others. The rub has three components in relation to the following:

- Atrial systole

- Ventricular systole

- Rapid ventricular filling during diastole

Evaluation

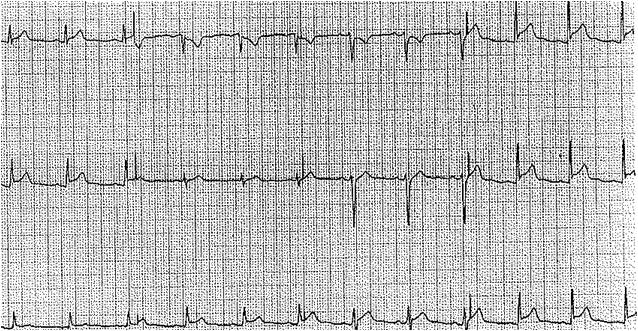

In evaluating a patient with suspected uremic pericarditis, an electrocardiogram is necessary. Electrocardiogram findings of pericarditis include diffuse ST and T-wave elevations. To distinguish these findings from an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, the ST and T-wave findings in pericarditis are typically diffuse and not localized to coronary artery territory. Normalization of the ST segment and diffuse T-wave inversions are seen in later stages.[17]

Cardiac biomarkers may also be elevated, i.e., troponins, but are not necessary to make the diagnosis.

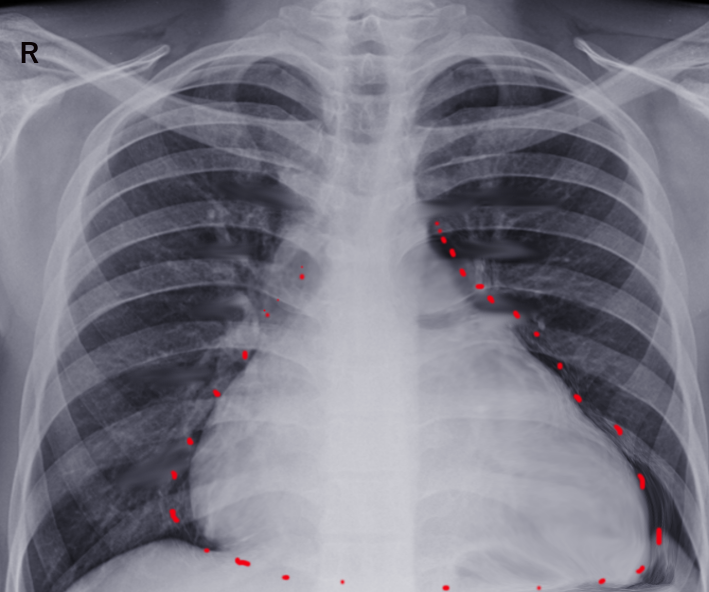

A chest X-ray can reveal an increased cardiac silhouette, which may represent an effusion.[7] Other imaging options include cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography, which can be used to diagnose pericarditis.[18] However, gadolinium should be avoided in patients having advanced renal disease because of the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF). A high CT attenuation indicates an exudative pericardial effusion and correlates with pericardial fluid protein, albumin, white blood cell (WBC), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), protein ratio, and albumin gradient.[19]

An echocardiogram is also very important to confirm or further evaluate the severity of uremic pericarditis. The echocardiogram will reveal a restrictive pattern due to the stiffness of the fibrous pericardium as a result of adhesions. In up to 50% of uremic pericarditis, pericardial effusion is noticeable on the echocardiogram. It is also important to note that pericarditis is primarily a clinical diagnosis; lab work and imaging will help aid the diagnosis but are not necessary to make the diagnosis.[10]

Routine blood work includes WBC count with differential count, inflammatory markers, renal and liver function tests, and creatine kinase troponins.[20] It is common to find raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein.[21]

A pericardial biopsy is not routinely performed, but it can reveal non-necrotizing or necrotizing fibrinous pericarditis in constrictive pericarditis, or it can be normal.[22]

Treatment / Management

Initial treatment for uremic pericarditis has multiple options. The preferred method is to institute dialysis or intensify dialysis for patients who have been on dialysis already.[20] Uremic pericarditis has been shown to respond rapidly to dialysis, leading to the resolution of chest pain and pericardial effusion in most cases. Effective dialysis therapy has been observed to be helpful in over 50% of cases.[7]

Anti-inflammatory agents and steroids are recommended in the guidelines for patients who fail to respond adequately to dialysis, but colchicine is not indicated in severe renal impairment.[20] Anti-inflammatories such as indomethacin may provide some relief for pain but have not been shown to be successful in eliminating uremic pericarditis. The use of steroids has been controversial in that it does provide relief. Still, it also increases the risk of recurrence along with potential side effects such as hyperglycemia, the risk of osteoporosis, and neurologic effects in the elderly. Low-dose corticosteroids can be used in patients unable to take NSAIDs for various reasons, such as adverse effects or contraindications.[23] Intrapericardial steroid injections have also been studied, but this approach is rarely used due to the risk of hemothorax, infection, pneumothorax, cardiac arrhythmia, and pneumopericardium.

If there is treatment failure with dialysis, the recommendation is to perform pericardiocentesis in patients with uremic pericarditis with effusion within 7 to 14 days. In patients with severe uremic pericarditis and effusion leading to cardiac tamponade, emergent pericardiocentesis is recommended.

Pericardiectomy is typically not the first-line management option and is only utilized for recurrent pericarditis with pericardial effusions. Recommendations are to pursue an echocardiogram every 3 to 5 days during the acute event to monitor pericarditis and effusion resolution.[14]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for uremic pericarditis is broad. Pericarditis has many different etiologies, which must all be ruled out before diagnosing. Although uremic pericarditis is the most common form of pericarditis in end-stage renal disease and dialysis patients, others can also occur and warrant appropriate evaluation. These other causes include:

- Infectious (viral, bacterial, fungal)

- Inflammatory (systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, vasculitis)

- Metabolic (hypothyroidism)

- Neoplastic (primary or metastatic)

- Trauma (blunt or penetrating)

- Cardiac (postpericardiotomy syndrome, myocardial infarction, aortic dissection)

- Medication-induced (i.e., hydralazine, methyldopa, procainamide, minoxidil)[15]

Prognosis

Overall, the resolution of uremic pericarditis is excellent, seen in 85 to 90% of patients.[24] However, the risk of recurrence becomes more likely with every episode of pericarditis. Uremic pericarditis is strongly associated with significant morbidity and occasional mortality. 3-5% of patients with uremic pericarditis may develop hemorrhagic pericarditis.

Complications

The major life-threatening complication of uremic pericarditis is the development of cardiac tamponade. If a rapid pericardial effusion accompanies uremic pericarditis, this has the potential to prevent the heart from functioning in pumping blood to the rest of the body. The increased pressure in the pericardium will restrict the heart from contracting and pumping blood. A typical presentation of cardiac tamponade includes hypotension, increased jugular venous distension, pulsus paradoxus, and distant heart sounds. An electrocardiogram may show electrical alternans, which is a discrepancy in voltage caused by the heart floating within the pericardium due to the effusion. The treatment for this is emergent pericardiocentesis.[4][14]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Uremic pericarditis is thought to result primarily from toxin accumulation leading to pericarditis. As such, there is not much the patient can do beyond receiving dialysis and exercising medication compliance. However, patients with chronic kidney disease should know that uremic pericarditis is one of the complications, and in case of chest pain, they should seek medical help. Patients who are already on dialysis should be made aware that non-compliance with renal replacement therapy could lead to many complications, and uremic pericarditis is one of them.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

As part of an interprofessional team, all healthcare personnel must be aware of the potential differential diagnoses in a patient complaining of chest pain. Clinicians will make the diagnosis, but other caregivers (e.g., nurses and pharmacists) will also be involved. Consult with a specialist, such as a nephrologist or a cardiologist, may be necessary. Nurses can assist with patient evaluation and counsel the patient once there is a definitive diagnosis. Pharmacists will play a crucial role in customizing the patient's medication regimen around dialysis, performing medication reconciliation, and counseling the patient on their drug regimen. All interprofessional team members must maintain accurate and updated patient records so everyone on the care team can access the same accurate and updated patient information. This, along with open communication, informs everyone involved in the case of any concerns or changes in patient status. This interprofessional approach will yield the best patient results. [Level 5]

Although uremic pericarditis is easily treatable, grave diagnoses such as, but not limited to, ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), cardiac arrhythmias, aortic dissection, coronary artery dissection, and stent thrombosis must be ruled out before making the clinical diagnosis of uremic pericarditis. In addition, since the presentation of uremic pericarditis can be consistent with STEMI (chest pain, elevated troponin, and electrocardiogram findings), it is imperative to perform an adequate and thorough evaluation for every patient.